| |

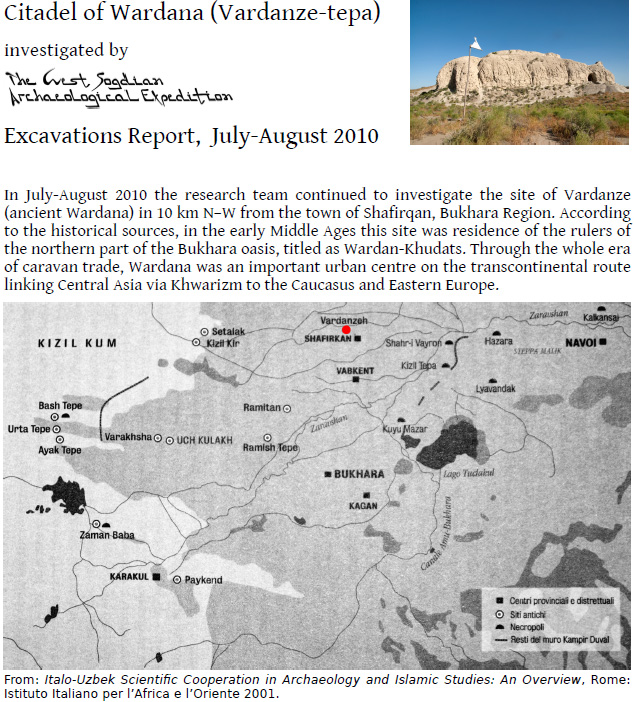

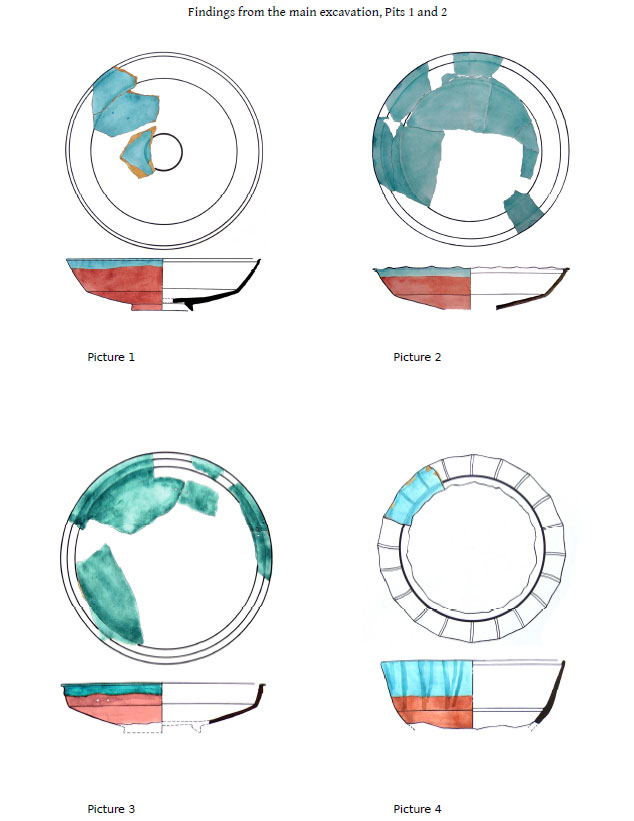

Archaeological excavation of an ancient city in the Oasis of Bukhara

The citadel of Vardanze. © A. Savchenko

The citadel of Vardanze. © A. Savchenko |

The site of Vardanze, the citadel is at the right. © Google

The site of Vardanze, the citadel is at the right. © Google |

The site of Vardanze was declared a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO World Heritage Commission as part of the transnational project "Silk Roads: Zarafshan-Karakum Corridor" on 17 September 2023.

Starting point and Relevance

The archaeological site of Vardanze lies north of the city of Bukhara in Central Uzbekistan and once competed with it for supremacy in the area. As introduction, please refer to the following contribution On the history of the ancient town of Vardana and the Obavija Feud by the two leading archaeologists of this project, Š. T. Adylov, J. K. Mirzaahmedov. Vardanze has not been excavated so far and important findings can be expected.

Goals

To excavate a well preserved site located in an area of rich historical past reaching back to the times of the Hephtalites, the Turkish Qaghanates, Sogd and the Arabs.

Partner in Uzbekistan

Dr. Š. T. Adylov, Senior Research Fellow, Samarkand Institute of Archaeology

Dr. J. K. Mirzaahmedov, Leading Research Fellow, Samarkand Institute of Archaeology

Project team

Dr. J. K. Mirzaahmedov, Leading Research Fellow, Samarkand Institute of Archaeology, Project Leader

Dr. Š. T. Adylov, Senior Research Fellow, Samarkand Institute of Archaeology

Dr. Silvia Pozzi

Ilaria Vincenzi

On the history of the ancient town of Vardana and the Obavija Feud

Š. T. Adylov, J. K. Mirzaahmedov

Slightly abbreviated contribution from: Eran ud Aneran Webfestschrift Boris Marshak 2003

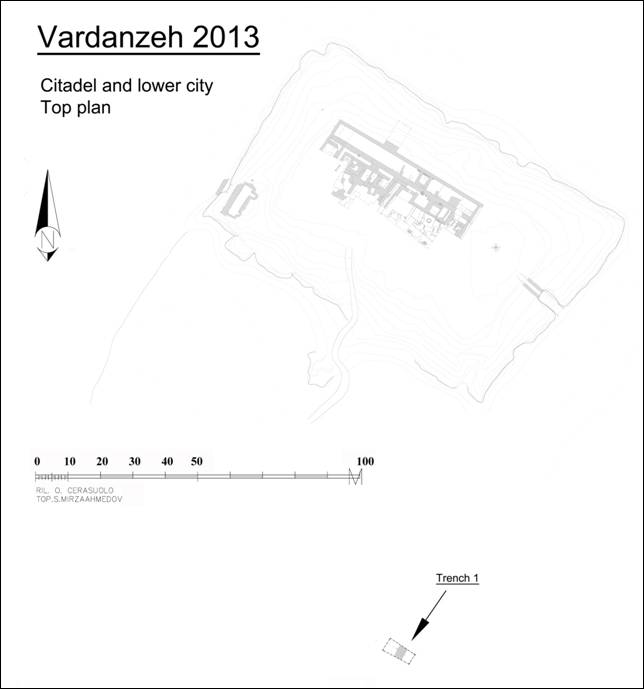

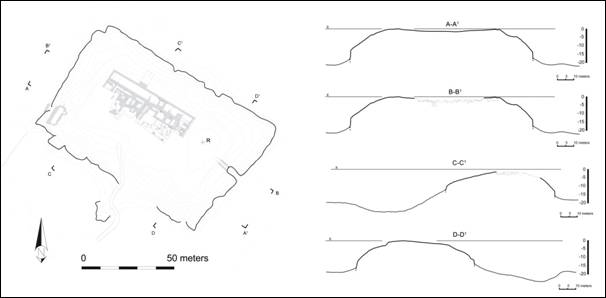

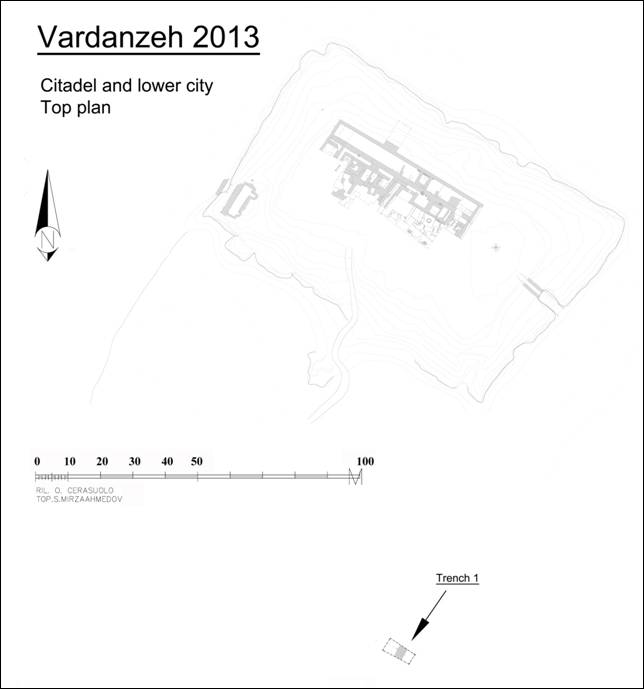

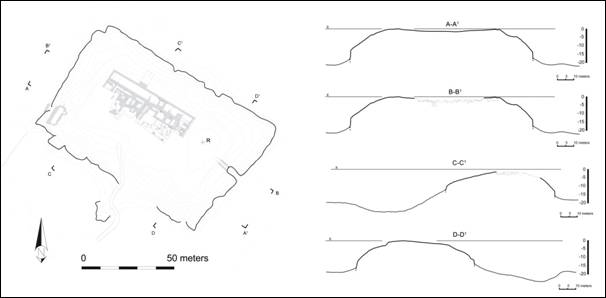

In the territory of the ancient irrigated land of Bukhara, at about 7 km in northeast direction from the provincial centre of Šafirkhan, lie the ruins of an ancient town called by the local people Kurgan-Vardanzeh. According to a subdivision common to other towns of its time, Vardanzeh was dominated by an ark-citadel with a lower town, the šahristan. At the present time only the rectangular-plan citadel is discernible. It extends in an east-west direction with an area of 0,5 ha and it is 15-16mts high. It is entirely surrounded by a moat that reaches 20 m in depth, obviously filled with water in antiquity. The šahristan is oriented along the north-south axis, south of the citadel. From the 19th to the beginning of 20th century it reached the apex of its importance while nowadays it appears isolated and mostly invaded by sand. For this reason the dimensions and shapes of the šahristan must be determined theoretically. It should be said that at a hidden level in the suburban part there is the rabad. As it is well-known, what is now the citadel, was until the 19th century a vast dwelling centre. Here was produced a kind of glazed ceramic very popular in the zone. This ceramic ware represents the last stage of the artistic development of Bukhara glazed ceramic ware of 18th-19th century, well-known even outside Bukhara. The decline of Vardanzeh is connected to the desertification of the periphery of the Bukhara Oasis. Such a process, already observed by E. K. Mejendorf at the beginning of 19th century (  , 1975, 85), resulted in a concentration of the people from the peripheric area to the centre of the Bukhara Oasis. During the 30's of 20th century Vardanzeh was abandoned and its inhabitants founded a new centre: Vardanzeh-Kukhna, 2 km south of the former. Vardanzeh-Kukhna still exists. , 1975, 85), resulted in a concentration of the people from the peripheric area to the centre of the Bukhara Oasis. During the 30's of 20th century Vardanzeh was abandoned and its inhabitants founded a new centre: Vardanzeh-Kukhna, 2 km south of the former. Vardanzeh-Kukhna still exists.

The citadel of Vardanzeh is one of the most well-known historical monuments of the region. Vardanzeh is mentioned often in the medieval written sources. In the Early Middle Ages it was the capital of a small but rich province whose governors were considered as important as the Lords of Bukhara, the Bukhar khudat. The celebrated medieval historian Naršakhi (10th century), originally from the village of Naršakh not far from Vabkand and author of the 'Tarikhi Bukhara' called this ancient town Vardana. With the same name it is mentioned in the works of Arab geographers of 10th century Al-Istakhri (Kitab al-Masalik va-l-Mamalik) and Tabari (Tarikhi al-Mulkba-l-Rasul). Another Arab geographer of 10th century al-Mukhaddasi (Akhsan at-Takhsim fi ma'rifat al-dalim) called this site Avarzana. Then, on other two Arab geographers, as-Sam'ani (12th century, Kitab al-Ansab) and Yakut al-Khamavi (13th century, Mu'jam al-Buldan) in their works reported both Vardana and Varzan ( , 1993, 63). The latter authors said also that in the Bukhara Oasis existed two sites with the same name Vardana or Varzan1 . Probably, Vardana should be considered the true name because it is reported more often in written sources and because the suffix '-zi' recurs in the names of modern localities. In Neopersian (Dari) it means 'place', 'zone'. The particle '-zi' is present in the names of ancient villages of the Bukhara region (for example Vaganzi, Isamzi, Paljanzi, etc.). So, the toponimous Vardanzi means 'the place of Vardana'. The etymology of this old name is unknown. , 1993, 63). The latter authors said also that in the Bukhara Oasis existed two sites with the same name Vardana or Varzan1 . Probably, Vardana should be considered the true name because it is reported more often in written sources and because the suffix '-zi' recurs in the names of modern localities. In Neopersian (Dari) it means 'place', 'zone'. The particle '-zi' is present in the names of ancient villages of the Bukhara region (for example Vaganzi, Isamzi, Paljanzi, etc.). So, the toponimous Vardanzi means 'the place of Vardana'. The etymology of this old name is unknown.

Vardana is recorded by Naršakhi at length. In the XIIIth chapter of his History of Bukhara he reports an ancient legend about the foundation of this settlement which he considers a village. According to the legend, Vardana was founded by a Persian prince of the Sasanian dynasty called Shapur a son of the šah Khosrow. After quarrelling with his father, Shapur went to Bukhara where the local governor, the Bukhar khudat, received him with great honour. Shapur loved to hunt and the Bukhar khudat gave him the uncultivated land in the north of Bukhara where many wild animals lived. The prince ordered a great canal to be dig in this area, called in his honour Šapurkam. The simple people called it 'Šafurkam'. The new owner founded many villages along the canal, among which was Vardana. The latter was Šapur's residence and the centre of his feud 'Obavija' ( , 1991, 110-111). The prince and his successors, who, after a short time became kings, had the title of 'Vardan khudat'2 . Naršakhi also mentions Vardana in the IV chapter of his book: according to his description Vardana was a great village with a huge stronghold which, in ancient times was the residence of the kings but in the days of the historian did not exist anymore. The founder of Vardana was Malik (king) Šahpur (Šapur). Vardana was on the border with Turkestan3 and, consequently, it had a great strategic, trading and producing importance. Here existed a weekly bazaar and here was produced a kind of material called 'zandaniji' as precious as Chinese silk. Naršakhi, then, said that Vardana was more ancient than Bukhara ( , 1991, 110-111). The prince and his successors, who, after a short time became kings, had the title of 'Vardan khudat'2 . Naršakhi also mentions Vardana in the IV chapter of his book: according to his description Vardana was a great village with a huge stronghold which, in ancient times was the residence of the kings but in the days of the historian did not exist anymore. The founder of Vardana was Malik (king) Šahpur (Šapur). Vardana was on the border with Turkestan3 and, consequently, it had a great strategic, trading and producing importance. Here existed a weekly bazaar and here was produced a kind of material called 'zandaniji' as precious as Chinese silk. Naršakhi, then, said that Vardana was more ancient than Bukhara ( , 1991, 98). , 1991, 98).

The information of Naršakhi is very interesting but controversial. In one part it is said that Vardana was probably founded by Šapur on the uncultivated land left by the lord of Bukhara, but in the preceding chapter that Vardana was older than Bukhara. Then, it is not clear if there existed a king called Šapur. It is well-known that during the Sasanian period there were two šah called Khosrow: Khosrow I Anoširwan (531-578) and Khosrow II (590-628). Other historical written sources do not say anything about a son of one of them called Šapur who escaped to Bukhara. It is not improbable that 'Šapur' is a name but a title4 . So, the name of this legendary prince, if ever existed, probably was not 'Šapur' and, consequently, the name 'Šapurkam' simply means 'the canal of the prince' 5 . This canal if it existed at all was recorded soon as 'Šafirkan'. Researches showed that this is not an artificial canal but one of the tributaries of Zerafšan. The archaeologists proved that the villages along its banks existed in the first centuries B.C. On the surface of Vardanzi were found fragments of ceramic ware dated to 4th-5th century B.C. and even older. The cultivation of the region started long before the first Sasanian, Ardašir I Papakan, was enthroned (approximately 226 A.D.). In our opinion, the legend of prince Šapur is only partly based on real facts but it is difficult to establish how it is really connected to the canal. Probably these events happened in the time of the Hephtalites (second half of 5th century- 60's of the 6th century). The huge Hephtalite state extended over a great part of Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Northern India. It was a confederation of territories, more or less independent but linked to the central authorities through alliance agreements. The region of Bukhara was one of the most important feuds ( , 1998, 21). A king was at the head of this confederation but he had not absolute power over the governors. , 1998, 21). A king was at the head of this confederation but he had not absolute power over the governors.

There were several wars between Persia and the Hephtalite kingdom and the former was always defeated with the result that the Sasanians had to pay a regular tribute to the Hephtalites. Even the most powerful of the Sasanian šah -Khosrow I- had to pay tribute for a certain period, so it is not improbable that one of the Persian princes exiled by him found a perfect shelter among his father's strongest enemies. In this case his protector was the governor of Bukhara whose territory was situated close to the right bank of Jaykhun- Amudarja. This river was the borderline between Iran and the Hephtalite state. The governor of Bukhara received the prince for political reasons and later, according to an ancient aristocratic costume, they became relatives through the marriage of Šapur with one of the daughter of the Bukhar khudat. In this way the prince became a vassal of the lord of Bukhara and the land of Vardana was intended as the marriage settlement of the woman. Certainly this land had been cultivated since antiquity and Vardana already existed along the tributary river.

It is not improbable that in this period there were still some parts uncultivated where wild animals lived. It is worth noting that in the same period this territory had not such a strategic and economic importance. It was on the border between the cultivated lands and the steppes, often threatened and far away from the main trade routes. The fortified town of Vardana was outside of the Kampirak wall which surrounded the greater of the part of the Bukhara Oasis as a protection against nomad's attack6 .

This prince of whose existence it is not sure, lived with his wife in Vardana and protected the northern border of Bukhara. Probably he promoted the enlargement of the canal and the construction of smaller other ones in order to bring water to the fields and drinking water to the town and the villages. Maybe, it is for this reason that his name survived. So, the canal called 'Safara'- which, according to al-Istakhri, passed through Vardana- is this Šapurkam. Safara is a corruption of the name 'Šapur'7 .

To support this hypothesis we can report some facts obtained from the historical sources on the relations between Persians and the Hephtalites. The first fact is linked with the period of reign of the šah Peroz (459-484), the one who attacked the Hephtalites three times and every time was defeated. After the first war he was imprisoned but he was rescued by the Byzantine Basileus. After the second defeat he swore on his own life to pay a great tribute which he could not raise at once but in two years and he left his son Kavad as an hostage. The third incursion cost him his own life and his camp was captured together with his daughter who was taken as wife by the Hephtalite king Kun-khi ( , 1989, 250-251; , 1989, 250-251;  , 128-129)8 . The second fact is linked to the Mazdakite revolution which happened in Iran in 5th-6th century. The šah Kavad (488-531) tried to use disorders to suppress the great aristocratic families, the great landowners and the priests. The Persian aristocracy deposed Kavad and enthroned his brother in 496. Kavad escaped to the Hephtalite court where he had had friendly relations since his sister was married to their king. He knew that only the military Hephtalite power could support his return on the Sasanian throne. He also married the king's daughter, that is to say his niece. Kavad lived for three years among the Hephtalites and, after his requests, the king gave him a great army in order to conquer the throne of Iran in 499 ( , 128-129)8 . The second fact is linked to the Mazdakite revolution which happened in Iran in 5th-6th century. The šah Kavad (488-531) tried to use disorders to suppress the great aristocratic families, the great landowners and the priests. The Persian aristocracy deposed Kavad and enthroned his brother in 496. Kavad escaped to the Hephtalite court where he had had friendly relations since his sister was married to their king. He knew that only the military Hephtalite power could support his return on the Sasanian throne. He also married the king's daughter, that is to say his niece. Kavad lived for three years among the Hephtalites and, after his requests, the king gave him a great army in order to conquer the throne of Iran in 499 (  , 1940, 136). We do not know if the Hephtalite princess gave to Kavad any son. If he had existed he would have lived for sure at his grandfather's court for a certain period in order to allow the control of the Hephtalites over the Persian Empire. During the Middle Ages the custom of keeping hostages was a successful system to control aggression from the neighbouring countries. , 1940, 136). We do not know if the Hephtalite princess gave to Kavad any son. If he had existed he would have lived for sure at his grandfather's court for a certain period in order to allow the control of the Hephtalites over the Persian Empire. During the Middle Ages the custom of keeping hostages was a successful system to control aggression from the neighbouring countries.

So, we have the information about a long period of residence of Peroz and his son at the Hephtalite court. The first time Kavad was just a prince, the second time he was the exiled šah and a relative of the Hephtalite king. If it is correct to consider the residence of the Hephtalites as located in the region of Bukhara ( , 129), then our hypothesis could be considered likely and in Šapur of the legend could be recognized Kavad, while in the figure of the Khosrow of the legend could be recognized Peroz or his other son the usurper of Kavad9 . This is not improbable although also Khosrow I, son of Kavad, could be the considered the šah called in the legend Šapur. In the history of Persian-Hephtalite relations there was likely to have been some episode which agrees with this legend. , 129), then our hypothesis could be considered likely and in Šapur of the legend could be recognized Kavad, while in the figure of the Khosrow of the legend could be recognized Peroz or his other son the usurper of Kavad9 . This is not improbable although also Khosrow I, son of Kavad, could be the considered the šah called in the legend Šapur. In the history of Persian-Hephtalite relations there was likely to have been some episode which agrees with this legend.

|

|

|

| Brick wall at the citadel. © A. Savchenko |

|

|

It is important to mention also the rest of the area of the feud belonging to the Vardan khudat, Obavija. In the territory of the modern region of Šafirkan there is some ancient village with its name ending in '-Uba'. The toponimous 'Obavija-Uba' comes probably from the Persian 'ab', water. The Hephtalites led by their king Ghatifar were defeated by the Turks in the region of Bukhara around 567-568 and their state was destroyed. Bukhara with other lands was incorporated into the Turk Qaghanate. The Kampirak wall lost its importance as the territory of the Bukhara Oasis now became an internal province of the Qaghanate. There was no reason anymore for its maintenance and the relationships between Turks and Sogdians were friendly. Many Sogdian feuds recognized nominally the Turkic power but were substantially independent and were allowed to have their own coinage and make pacts among themselves.

The territory of Western Sogd was divided into several feuds and three were dominant: Bukhara was the centre of one of these and its governors kept the title of Bukhar khudat. The second big centre was Ramitan. This ancient town is mentioned in Arab sources as the second capital of the region of Bukhara. There are some hints to consider the name of its governors as 'X-n-kkhudat' ('Khunukkhudat'? the real pronunciation and etymology of which are obscure). One of the 'Khunukkhudat' is mentioned in the History of Bukhara where he is linked to the renewal of the destroyed Varakhša and another is mentioned as a governor who opposed to the advance of Qutayba ibn-Muslim ( , 1998, 22-25). The two capitals were both situated along the Silk Road. The third feud was Obavija with the Vardan khudat as governor. According to Naršakhi and Tabari the Vardan khudat were powerful governors and they could compete with the Bukhar khudat ( , 1998, 22-25). The two capitals were both situated along the Silk Road. The third feud was Obavija with the Vardan khudat as governor. According to Naršakhi and Tabari the Vardan khudat were powerful governors and they could compete with the Bukhar khudat ( , 1991, 111; , 1991, 111;  , 120-121). The reason of the flourishing of Obavija under the successors of Šapur was the new geopolitical reality. Obavija was situated on the border between the nomadic steppe and the territories along the Silk Road linking Bukhara and Samarkand, called 'Šahrakh' ('Main branch')10 . In every period, the steppe under nomadic rule did not only import but also export along this segment of the Silk Road. The Turks had their interests in trading with the Sogdians. The Sogdian colonies were settled along the Silk Road. For this reason the Vardan khudat exploited the important position of Obavija. According to Tabari it is arguable that Obavija had its golden age in this period. , 120-121). The reason of the flourishing of Obavija under the successors of Šapur was the new geopolitical reality. Obavija was situated on the border between the nomadic steppe and the territories along the Silk Road linking Bukhara and Samarkand, called 'Šahrakh' ('Main branch')10 . In every period, the steppe under nomadic rule did not only import but also export along this segment of the Silk Road. The Turks had their interests in trading with the Sogdians. The Sogdian colonies were settled along the Silk Road. For this reason the Vardan khudat exploited the important position of Obavija. According to Tabari it is arguable that Obavija had its golden age in this period.

In 706-7 the Arab general Qutayba ibn-Muslim crossed the Jaykhun and started the conquest of Sogd. In 712 the whole of Sogd, including Bukhara and Samarkand, was under Arab rule. The written sources record that the Vardana governor fiercely opposed the Arab advance. Tabari called him the king of all Bukhara ( , 120-121) and Naršakhi 'honoured king' ( , 120-121) and Naršakhi 'honoured king' ( , 1991, 111). Regarding this problem, it is said that after the surrendering of Taghšod (son of Bidun and the illustrious queen 'Khatun')12 to Qutayba, the governor of Vardana proclaimed himself king of the whole Bukhara ( , 1991, 111). Regarding this problem, it is said that after the surrendering of Taghšod (son of Bidun and the illustrious queen 'Khatun')12 to Qutayba, the governor of Vardana proclaimed himself king of the whole Bukhara ( , 1970, 279). Then, he continued the resistance to the conquerors as a king of all the people of this part of Sogd. As it is known, finally the Vardan khudat died and his feud was taken by the Arabs. Qutayba gave this domain to Tagšod as a sign of his loyalty to the conquerors and Obavija ceased to exist as an independent feud. Vardana too lost its importance ( , 1970, 279). Then, he continued the resistance to the conquerors as a king of all the people of this part of Sogd. As it is known, finally the Vardan khudat died and his feud was taken by the Arabs. Qutayba gave this domain to Tagšod as a sign of his loyalty to the conquerors and Obavija ceased to exist as an independent feud. Vardana too lost its importance ( , 1991, 111). Considering these facts, some scholars date the usurpation of the Vardan khudat to 707/8-709/10 ( , 1991, 111). Considering these facts, some scholars date the usurpation of the Vardan khudat to 707/8-709/10 ( , 1970, 279; , 1970, 279;  , 1989, 43). Developing these hypotheses, one can imagine in which circumstances the Vardan khudat proclaimed himself king of Bukhara. According to our opinion, the reason for this change of power are the previous events described in chapter XVIII of 'The History of Bukhara', where Naršakhi says that in the Bukhar khudat palace a strong opinion existed concerning the honour of 'Khatun'. The father of Tagšod was not the husband of Khatun but one of her bodyguards with whom she had an intimate relationship. As a result, a strong opposition was found in the court of Bukhara among the military class which wanted a noble and worthy person as a ruler. However, the queen who knew about the conspiracy prevented it. Later the expedition of Sa'id ibn-Osman -the representative of the Caliph in Khorasan (675/6)- Khatun included members of the aristocracy who opposed to her among the 80 hostages taken to Arabia by Sa'id. Later they all died heroically in the palace of Sa'id in Medina, after killing Sa'id himself ( , 1989, 43). Developing these hypotheses, one can imagine in which circumstances the Vardan khudat proclaimed himself king of Bukhara. According to our opinion, the reason for this change of power are the previous events described in chapter XVIII of 'The History of Bukhara', where Naršakhi says that in the Bukhar khudat palace a strong opinion existed concerning the honour of 'Khatun'. The father of Tagšod was not the husband of Khatun but one of her bodyguards with whom she had an intimate relationship. As a result, a strong opposition was found in the court of Bukhara among the military class which wanted a noble and worthy person as a ruler. However, the queen who knew about the conspiracy prevented it. Later the expedition of Sa'id ibn-Osman -the representative of the Caliph in Khorasan (675/6)- Khatun included members of the aristocracy who opposed to her among the 80 hostages taken to Arabia by Sa'id. Later they all died heroically in the palace of Sa'id in Medina, after killing Sa'id himself ( , 1991, 116-118). , 1991, 116-118).

After the death of the queen the struggle began again and there appeared several pretenders to the throne of Bukhara. The most powerful was the ruler of Obavija, who, during the period of Qutayba's incursions, was quarrelling with the Bukhar khudat. He considered himself as a descendant of the Sasanian house and so the legitimate and worth pretender to the throne of Bukhara. Tagšod was young, inexperienced and compromised because of his friends with the Arabs. The Vardan khudat was undoubtedly supported by the local population and army. According to Tabari he even defeated the Arabs during their first battle and his prestige increased ( , 121). According to Naršakhi, the Vardan khudat was originally from Turkestan. Qutayba was obliged to lead a long war against him and he pushed him many times out of the kingdom of Bukhara but the Vardan khudat escaped to his Turkish allies. Only after the Vardan khudat's death, Qutayba managed to give Bukhara to Tagšod. Then, Qutayba defeated the other pretender and the decentralizing ambitions of the local aristocracy. As a result, Tagšod accepted to conversion to Islam and his son was called Qutayba in honour of his patron ( , 121). According to Naršakhi, the Vardan khudat was originally from Turkestan. Qutayba was obliged to lead a long war against him and he pushed him many times out of the kingdom of Bukhara but the Vardan khudat escaped to his Turkish allies. Only after the Vardan khudat's death, Qutayba managed to give Bukhara to Tagšod. Then, Qutayba defeated the other pretender and the decentralizing ambitions of the local aristocracy. As a result, Tagšod accepted to conversion to Islam and his son was called Qutayba in honour of his patron ( , 1991, 93). , 1991, 93).

In the beginning of the 80's of 7th century, during the suppression of the anti-Arabic rebellion under Mukanna, the opposition was renewed by strong nomadic elements. The inhabitants of Bukhara remained pagan and this was one of the reason why the representatives of the Baghdad Caliphs at Bukhara rebuilt the Kampirak wall. Once more, Vardana was outside it, as a border fort. At the end of 9th century, in the time of Emir Ismail as-Samani, the wall already had lost its military importance. Naršakhi recorded one sentence of the Emir: 'While I am alive, I am the wall of Bukhara' ( , 1991, 112). Nevertheless, Vardana failed to restore its previous glory. , 1991, 112). Nevertheless, Vardana failed to restore its previous glory.

In the second half of 9th-10th century, several rustak appeared in the territory of former Obavija. According to Al-Istakhri in the territory of Bukhara there were 22 rustak, 15 of which were situated inside the Kampirak. Among the inside rustak is mentioned Arvan, where there was a canal with the same name ( , 1963, 163). Most likely, the centre of the rustak was situated in a place near to the town with the same name. If so it corresponds to a ruined old town situated approximately 7 km west of Vardanzeh. The local inhabitants call this place Jalvan. As Vardanzeh, it was inhabited also in the 19th century. In the Soviet period a new village called Jalvan appeared situated north of Vardanzeh where there was a canal called Jalvan. The canal was excavated in Soviet times so that its water could be used for cultivation of the northern territory. As for the place of old Jalvan, it was situated at the terminal part of the present day dry canal of Sultanabad which flows between Šafirkan and Pirmast. Modern Sultanabad corresponds to ancient Arvan. , 1963, 163). Most likely, the centre of the rustak was situated in a place near to the town with the same name. If so it corresponds to a ruined old town situated approximately 7 km west of Vardanzeh. The local inhabitants call this place Jalvan. As Vardanzeh, it was inhabited also in the 19th century. In the Soviet period a new village called Jalvan appeared situated north of Vardanzeh where there was a canal called Jalvan. The canal was excavated in Soviet times so that its water could be used for cultivation of the northern territory. As for the place of old Jalvan, it was situated at the terminal part of the present day dry canal of Sultanabad which flows between Šafirkan and Pirmast. Modern Sultanabad corresponds to ancient Arvan.

The other part of ancient Obavija including Vardana (on the right bank of Šafirkan) belonged to the external rustak. Among the 7 external rustak, Al-Istakhri recorded Šah-Balš ('Gift of the king') ( , 1963, 163). In the name we identify the legendary (or real?) gift of the Bukhar khudat (the king of the Hephtalites) to prince Šapur (Kavad?). It is necessary to mention that all the other external rustak are correctly identified around the Bukhara Oasis. So, the identification of the right bank of Šafirkan with the Šah-Balš is certain. Naturally, the centre of the rustak was Vardana. , 1963, 163). In the name we identify the legendary (or real?) gift of the Bukhar khudat (the king of the Hephtalites) to prince Šapur (Kavad?). It is necessary to mention that all the other external rustak are correctly identified around the Bukhara Oasis. So, the identification of the right bank of Šafirkan with the Šah-Balš is certain. Naturally, the centre of the rustak was Vardana.

In conclusion, the rich history of this ancient town with its surrounding settlements entirely deserves the interest of the authorities and the scientific community, in order to sponsor a big scale archaeological investigation for the study of the site.

Bibliography

Notes

1) Another village with the same name exists nowadays. It is called Vardana-Šajkhon, at c. 5 km east of Ramitan. In its north-east periphery there is the ancient corresponding town.

2) The title 'Vardan khudat' means litterally 'Lord of Vardana'. The ancient Iranian term 'khudah' ('khudat' according to Arab writings) means 'lord', 'governor', 'owner', etc. In the ancient period among the Iranians and the Turkish people it meant God (Allah). From the ancient Persian 'khudah' comes the Neopersian term 'khoja' (khujain) and the Russian ' ' (owner). ' (owner).

3) In Early and Late Middle Ages, Turkestan (the land of the Turks) meant South Russia, Kazakhstan, South Siberian steppes and also the desertic territory bordering the Central Asian oases. Just after the Middle Ages this term started to mean the whole of the geographic area of Central Asia.

4) In Middle Persian (Pahlavi) translation, 'Šapur' (more correctly 'Šah-pur') means 'son of the king', 'prince'. It is correct to suppose that Middle Persian knew a wide diffusion arounf Bukhara since 6th-7th century together with Sogdian. This is confirmed by historical sources, archaeological finds and in modern languages the ancient hydro-toponym were kept until the present moment of time. Probably for this reason Neopersian completely ousted Sogdian language in its historical territory.

5) In ancient Iranian languages the term 'kan' meant 'to dig', 'place of the canalized waters', 'canal'. In the region of Bukhara, where it is possible to find many hydro-toponym ending in '-kan', it is possible often to observe the form 'kam' ('Kharamkam', 'Kami-Zar', Kami-Dajmun', 'Kalkanrud', 'Kalkan-Ata', etc.). During the 19th century, at Bukhara, the term 'kam' signified long main canal, while a small canal was called 'jui' (aryk) ( , 1962, 134). , 1962, 134).

6) The study of the written sources and the archaeological and cartographic investigations showed that the Kampirak wall was built in two phases. The first one is dated to the Hephtalite period (end of the 5th-middle of the 6th century). The second phase is dated to the period between 782 and 831 and it is described in the XV chapter of the History of Bukhara. Between the two phases there was a long period when the wall had no ADYLOV-MIRZAAHMEDOV - On the history of the ancient ... http://www.transoxiana.org/Eran/Articles/adylov_mirzaakh...

importance. The second phase wall presents signs of destruction. Both the first as the second phase were conceived for defence against the nomadic Turkish tribes ( ). ).

7) As it is well-known, Naršakhi wrote his book in Arabic and in 11th century it was translated in Farsi by al-Kubavi, originary of Kuva (Ferghana). Nowadays it was preserved just the Persian version. Clearly, in the read and written Arab form, the name of the canal was 'Šafurkam', in accordance with the rules of Arab language and the local dialectal variations. Nevertheless, al-Kubavi does not simply 'adapt' automatically the arabized form of the canal but he reflects the adaptation according to the rules of literary Farsi (although he reflects the dialectal pronunciation as well). According to al-Istakhri, also his variant (without '-kam') was naturally arabized with more alterations. Possibly, the mistakes in the script were not due to the authors but to the copysts. In the place of 'šin' they could have written 'sin' which, in Arab script is almost identical. Such mistakes in calligraphy were quite common among the Middle Ages copysts. As a result of such a phonetic corruption, 'Šapur' could have be transformed in 'Safar'.

8) Kunkhi (Gunkhaz) is the name attributed to him by the Byzantine historian Priscus. According to Ferdousi his name was Khušnavaz and for Tabari Akhšunvar. Possibly, the latter variant was not a name but a title ( , 1989, 251). , 1989, 251).

9) Among the šah of the Sasanian dynasty, Khosrow I was not only the most powerful but also the most famous. His predecessors and successors on the throne of Iran had this name not only in the literatury tradition but also in the representations of the Sasanian šah in the national monuments.

10) The constructions were built along the left bank of the Rudi-Zar canal (alias Nakhri-Zar, Rudi-Šarg, Nakhri-Bukhoro, Kharamkan) which during the ancient time was identified with the course of the lower reaches of Zerafšan. Now this course is called Šahrud.

11) In the ancient time the administrative and political borderlines were often fixed along a river, firstly because a river was a natural obstacle, secondly because it was a steady dividing line.

12) Naršakhi called the queen just 'Khatun'. According to other historians her name was Kabaj-khatun (Tabari) and Khutak-khatun (?) (Kh-t-k-khatun) (Asam ibn-Kufi). Probably this name is actually a title ( , 1998, 24). , 1998, 24).

© The Authors

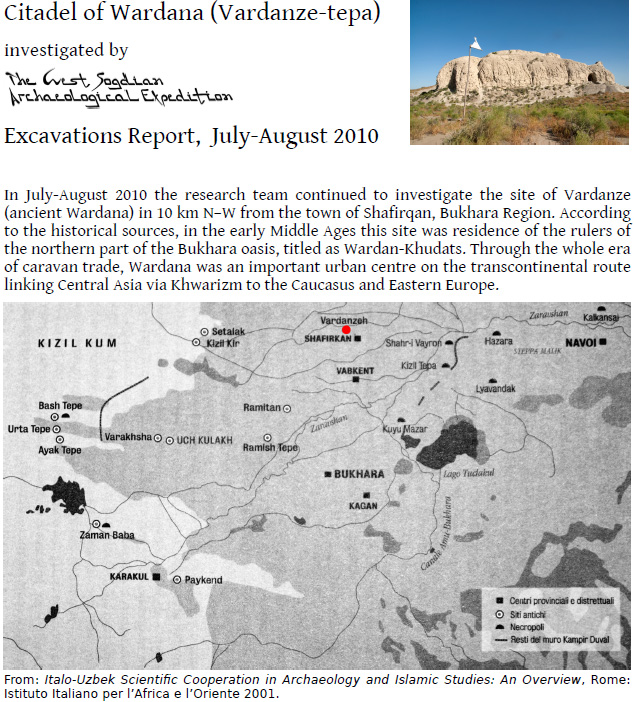

Excavations at Vardanze (Wardana)

Shafirqan District, Bukhara Region

August-September 2009

In August, 2009 the West Sogdian Archaeological Expedition 1

started investigations of the site of Vardanze, ancient Wardana, lying

on the northernmost border of the Bukhara oasis, at the southern edge

of the Qizil-Qum desert.

The principality of Wardana was one of the main centres of civilisation

in the oasis before the Arab invasion, competing in wealth and importance

with Bukhara itself. The course of historical events and a general description

of the site can be found here: http://www.transoxiana.org/

Buried under the sand in 1868 2 , Vardanze

has never received the same attention as other major sites in the Bukhara

oasis (Warakhsha, Ramitan, Paykend) 3.

Recently, a topographical survey was made by the Italian archaeological

team who also laid a probing trench near the southern corner 4

of the main wall of the citadel. 5

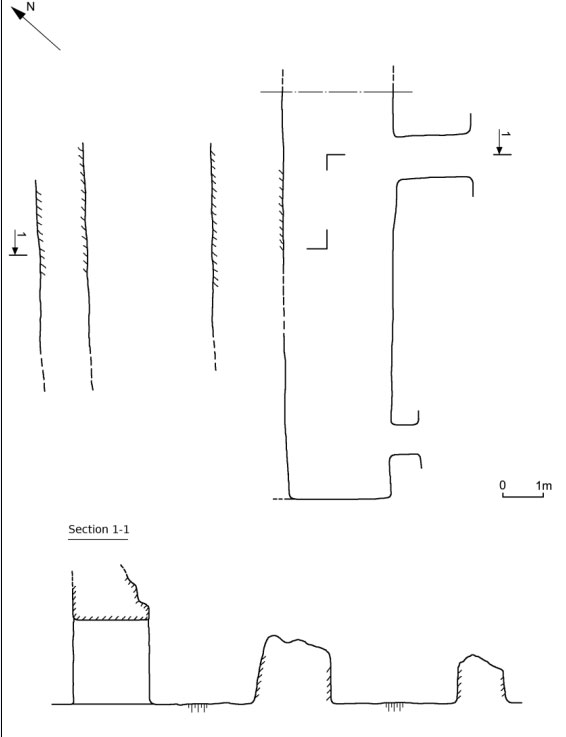

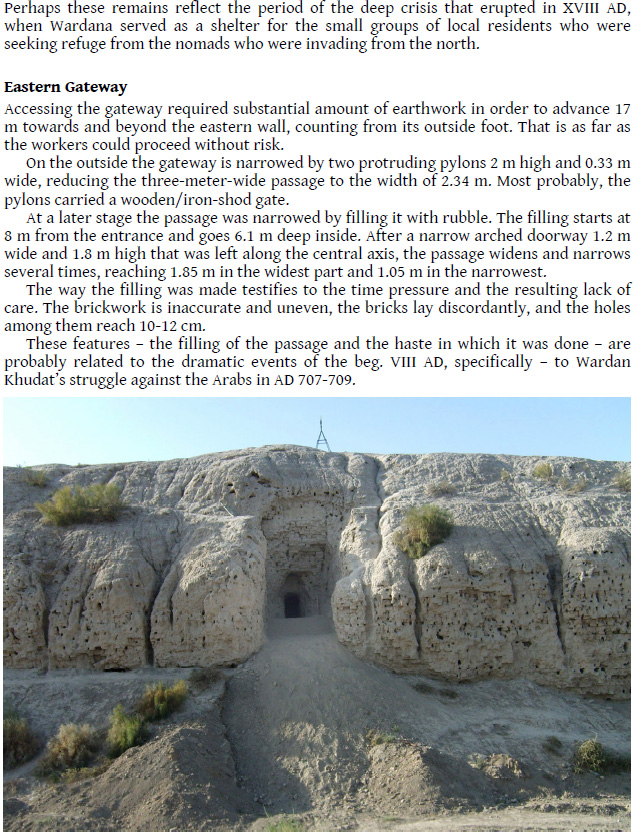

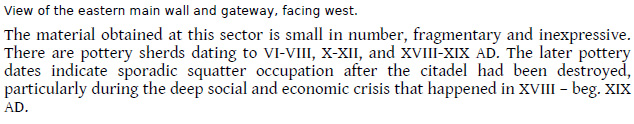

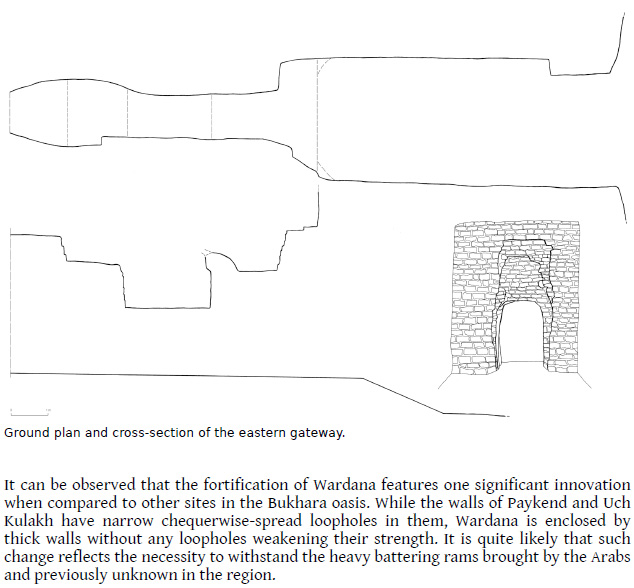

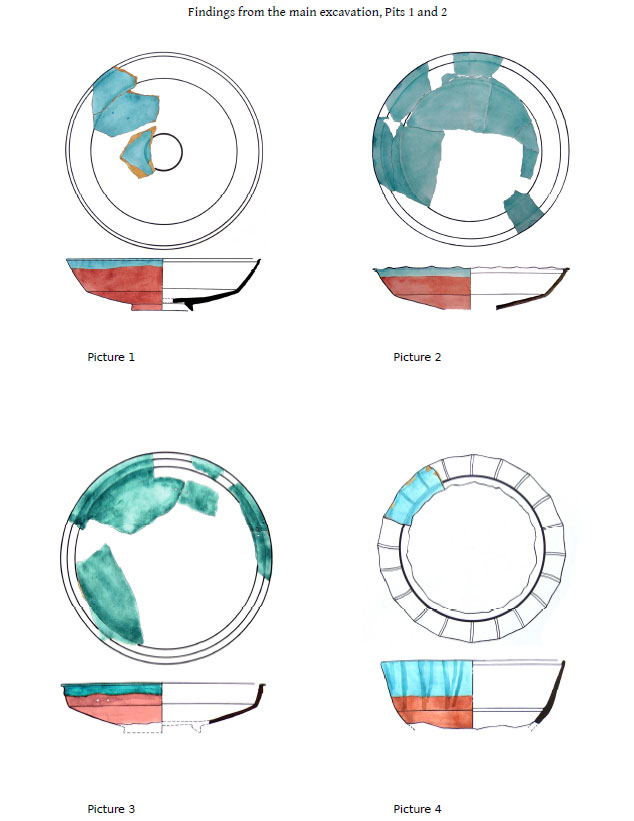

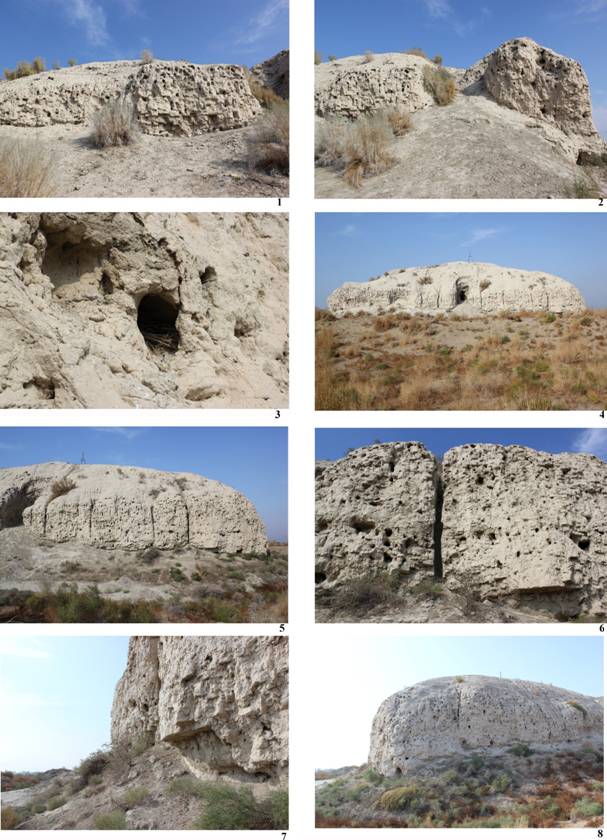

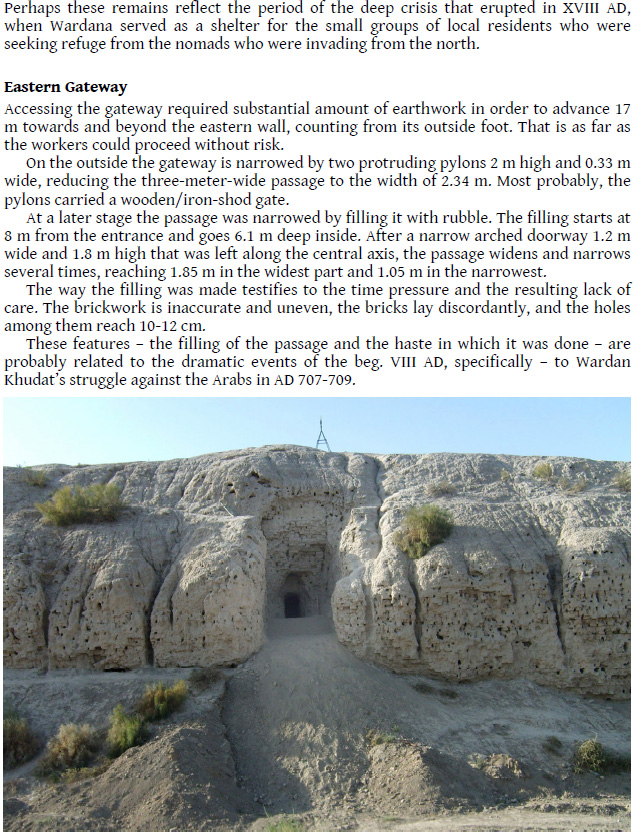

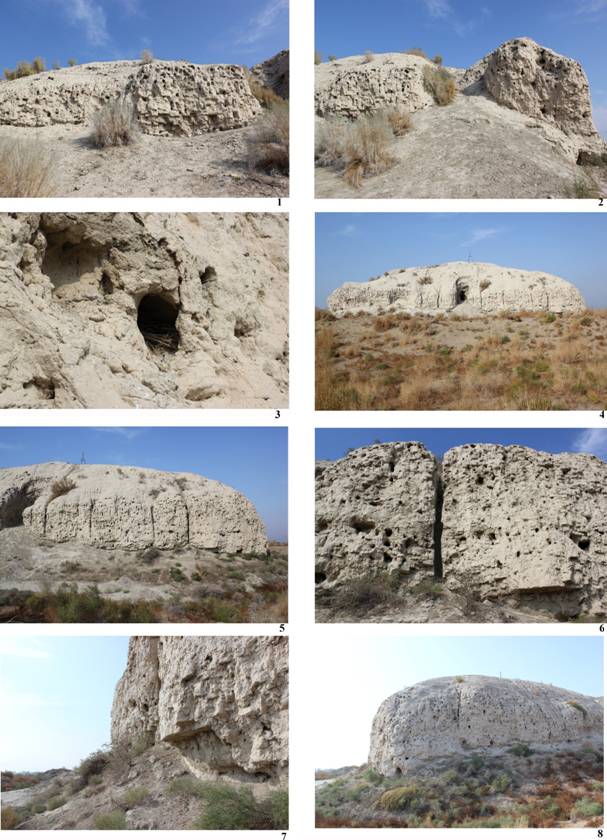

Plate 1: southern corner of the citadel

and the N–E perimeter wall, ca. 15 m in height.

Plate 1: southern corner of the citadel

and the N–E perimeter wall, ca. 15 m in height. |

|

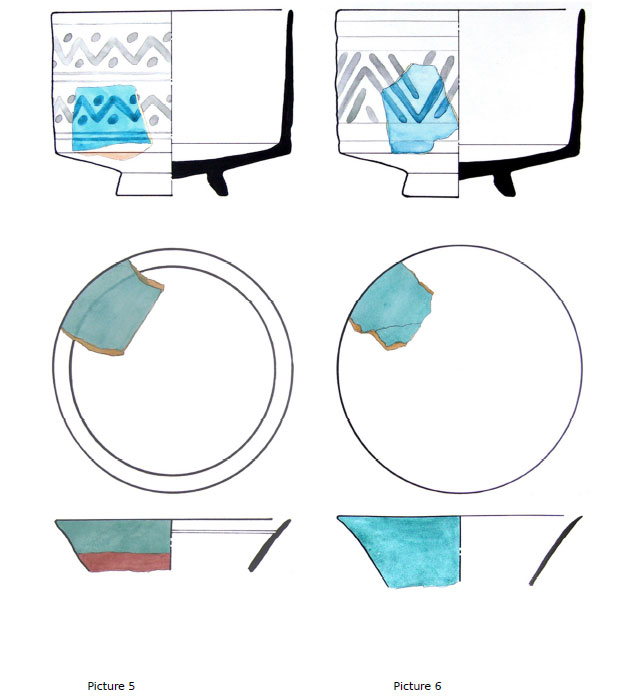

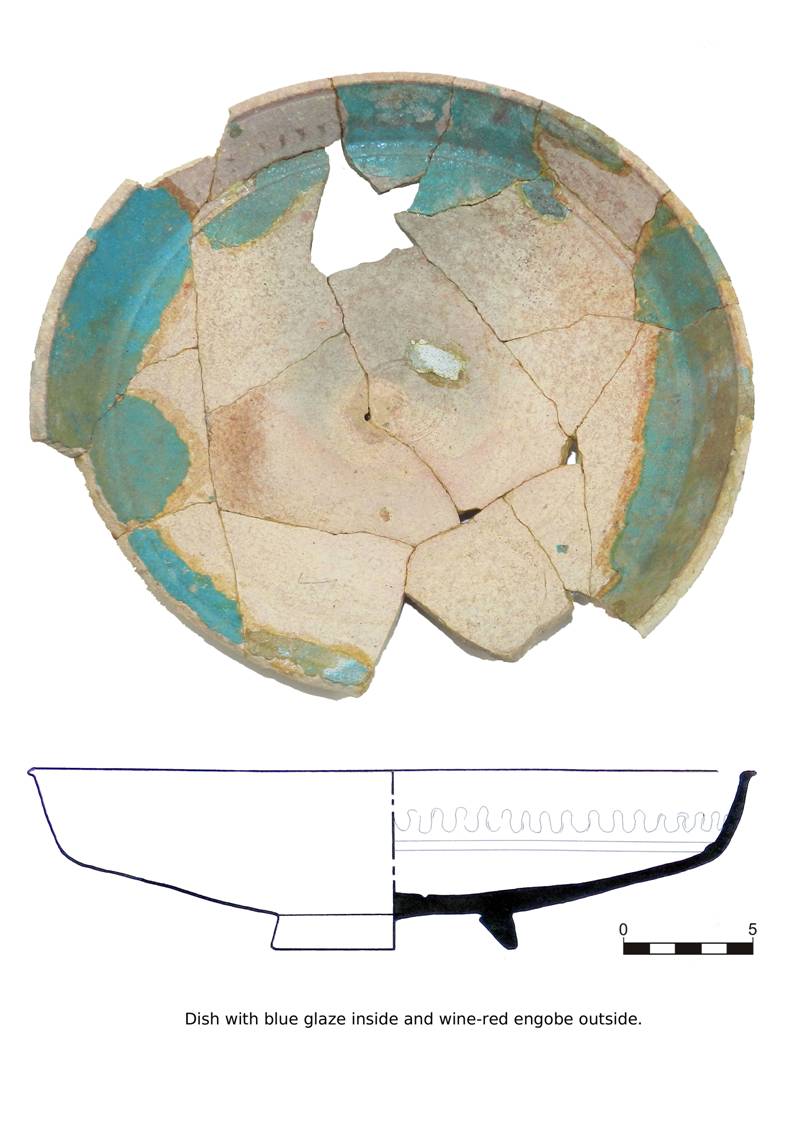

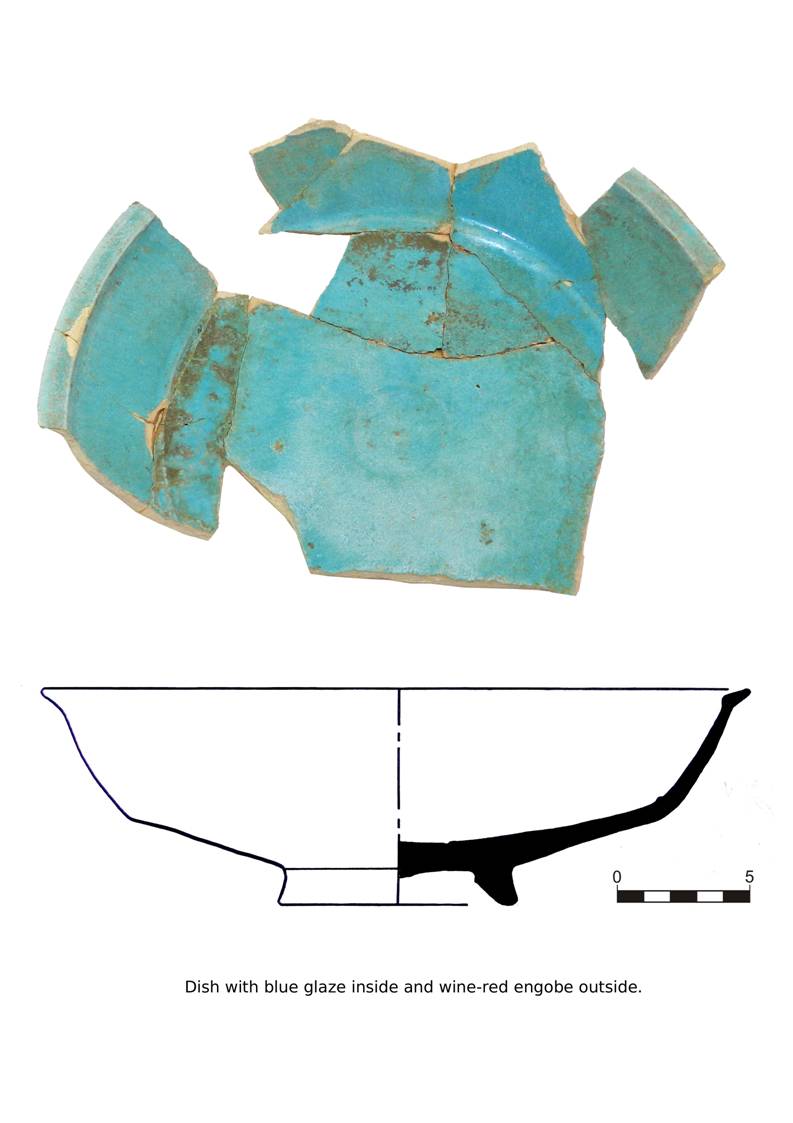

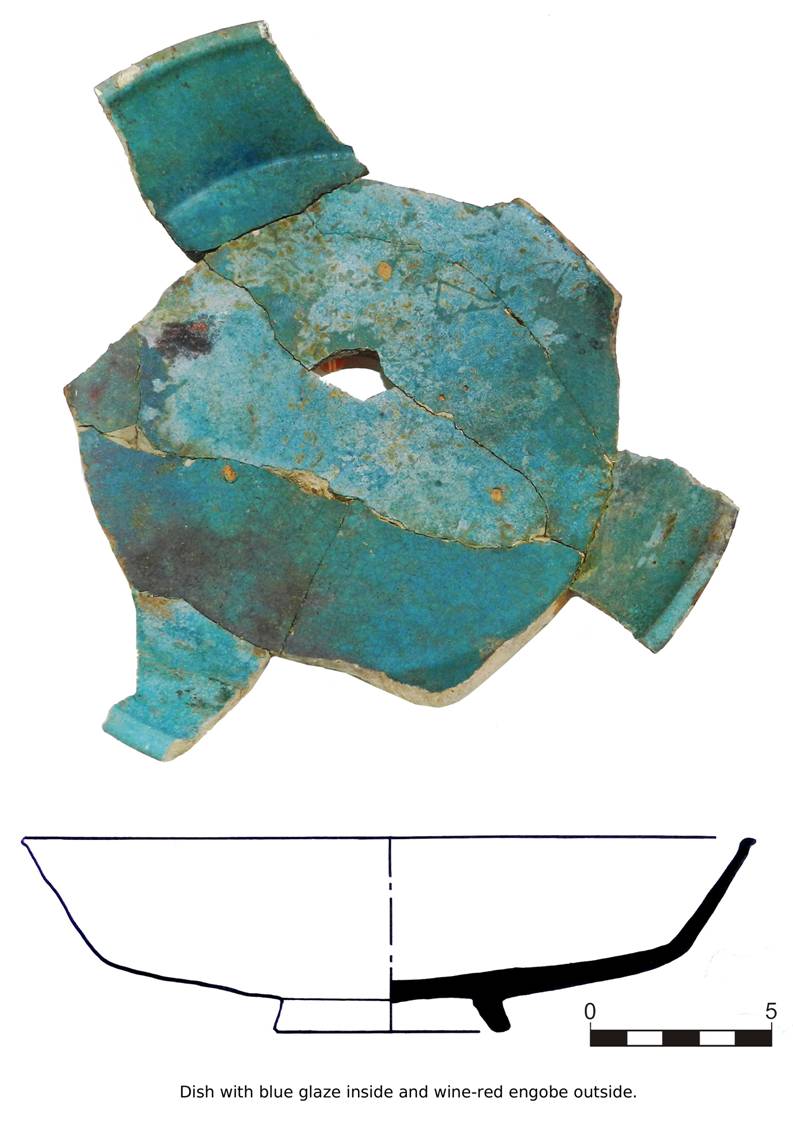

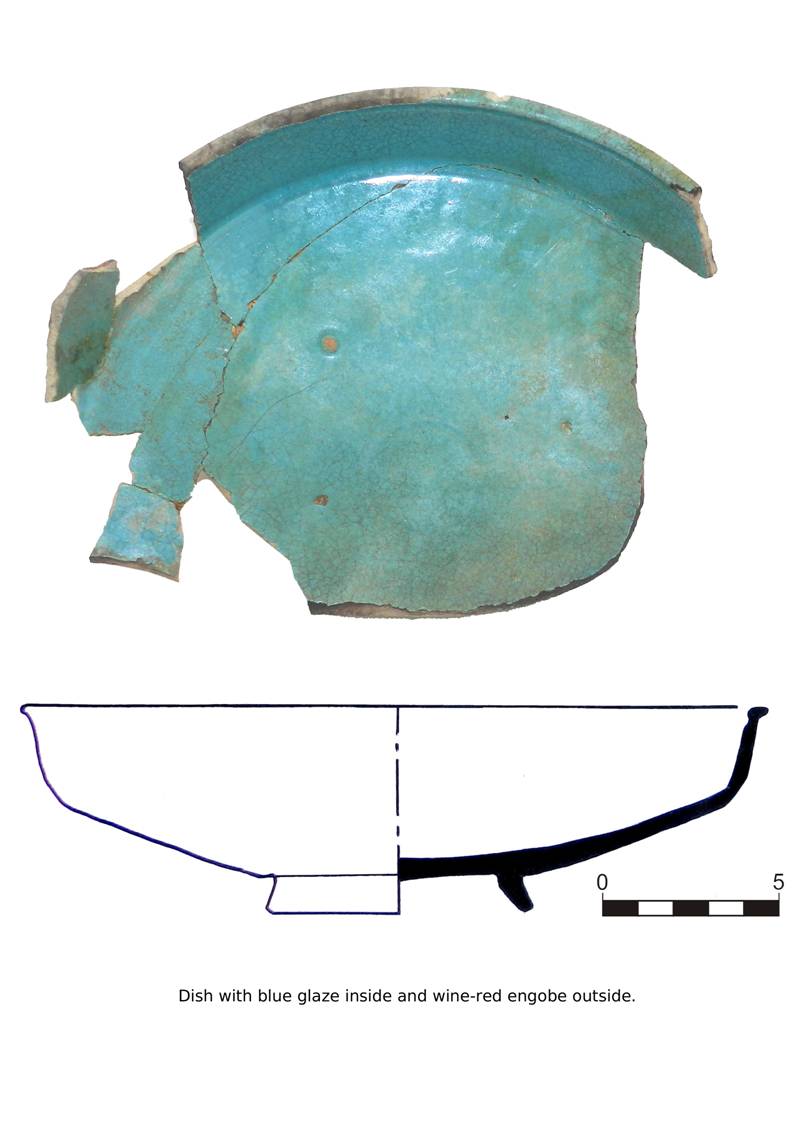

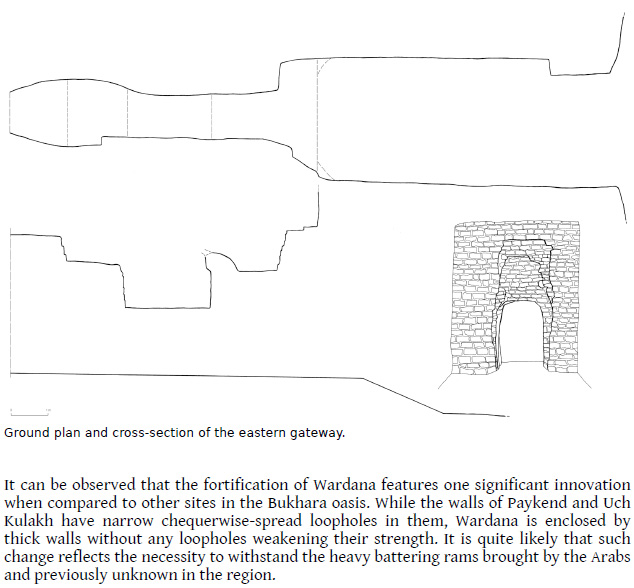

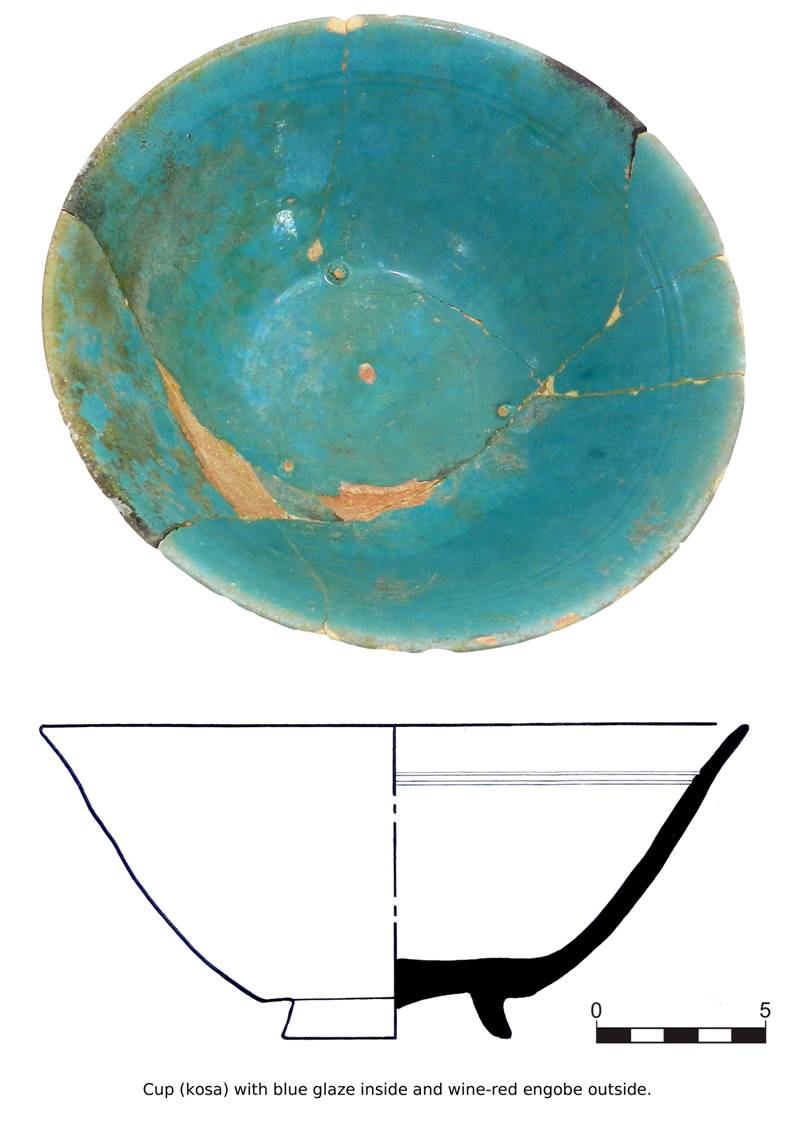

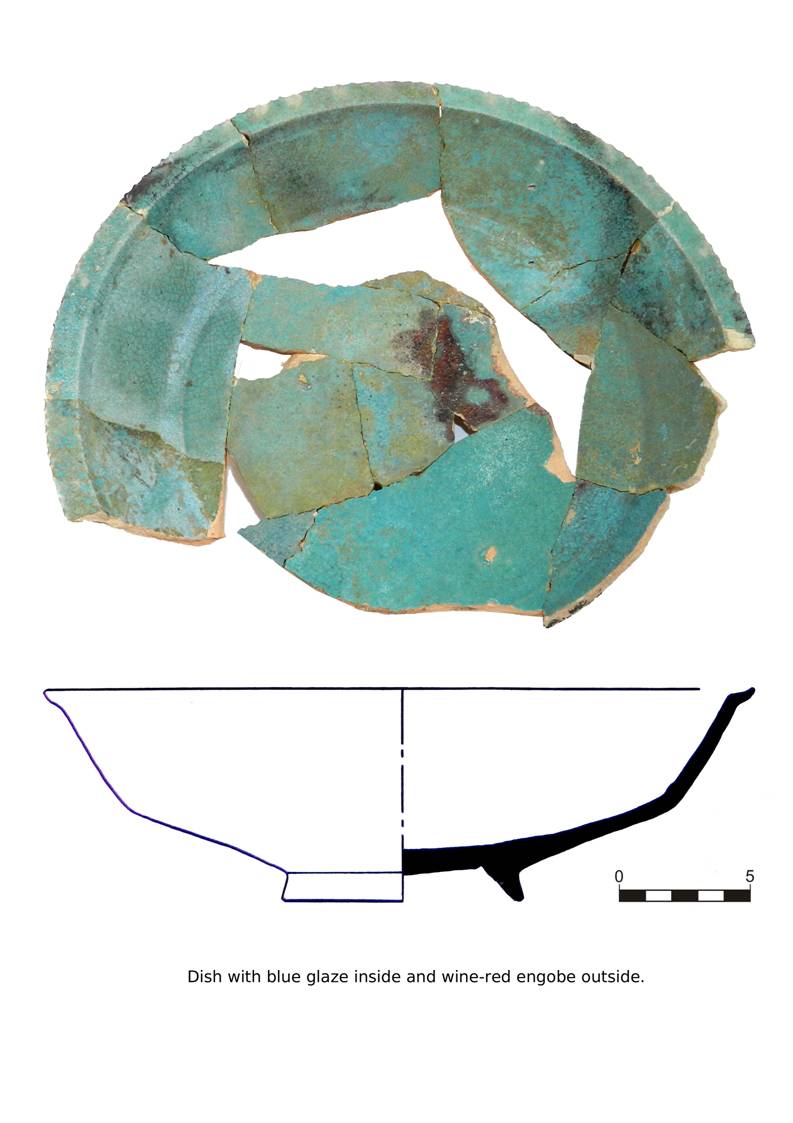

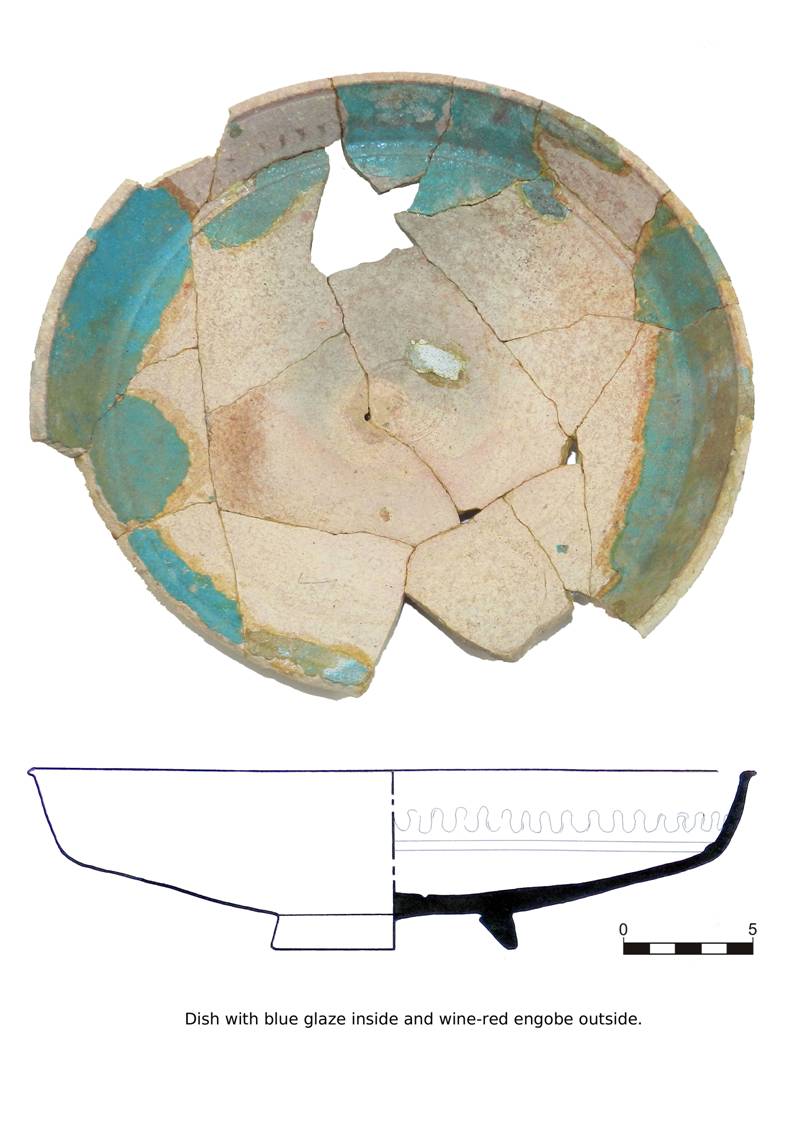

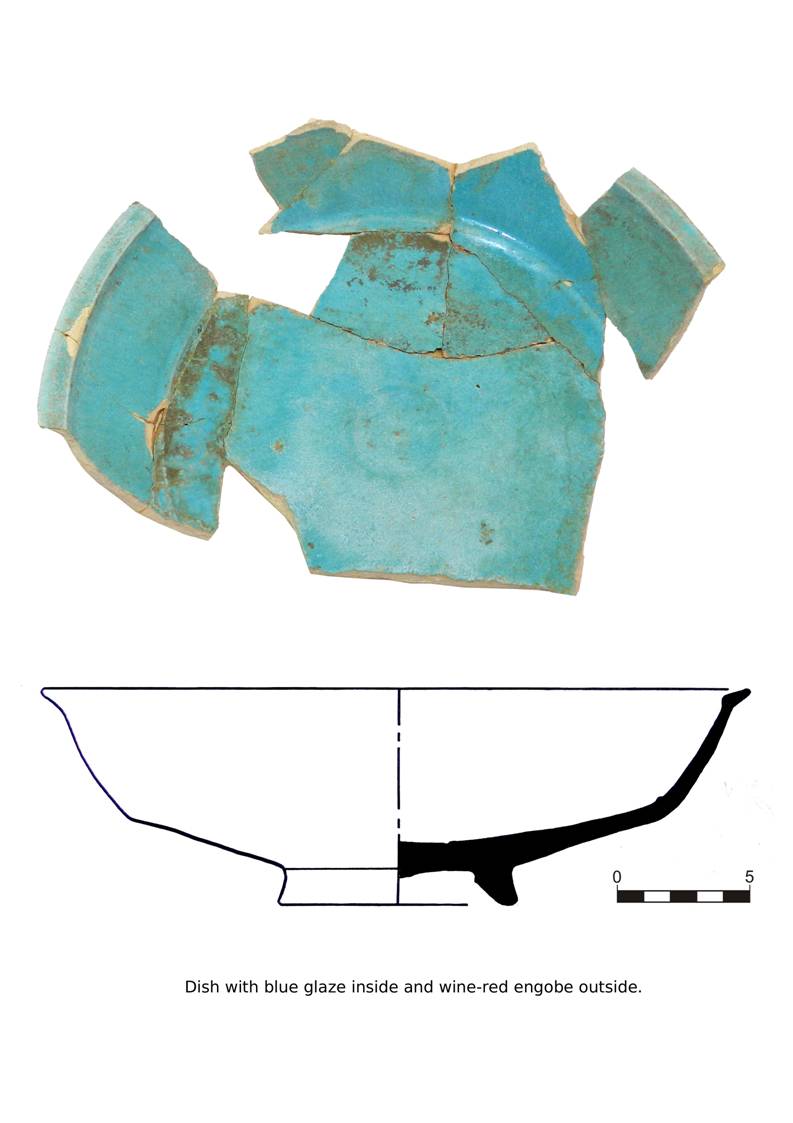

The array of the artefacts collected from the surface of the

site before the start of the excavations dated to the time spectrum

as wide as IX–XIX AD. Among those, the blue glazed pottery sherds

of XII–beg. XIII AD were the most numerous, next to them in frequency

of occurrence being the fragments of pottery with yellow and greenish

glaze characteristic for 1st half–mid XVIII AD.

Two separate trenches were laid as described below.

Trench 1

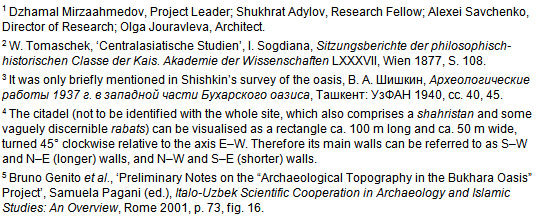

16×8 m, divided by a stratigraphic kerb 1 m wide into two equal

parts, lies in the centre of the flat top of the citadel, along its

S–E – N–W axis, slightly shifted to the N–W.

|

|

|

| Plate 2: Work in progress in the flat centre

of the citadel |

|

|

The excavations in this sector revealed a top stratum featuring the

remains of collapsed buildings covered with sand and loess. Along the

northern border of the trench, at 20-30 cm deep were found the remains

of a main wall 1,5-2 m wide, extending beyond the border of the trench.

Given the impressive dimensions, it can be safely assumed that this

main wall is part of the fortification of the site.

In the western part of the dig, at ca. 0,8-1 m were found some remains

of walls, benches (sufas), hearth pits, and rooms with poorly preserved

contours, laid with adobe and large sun-dried bricks.

The eastern part of the dig was full of alluvial sand and loess, and

can be assumed to be an open yard adjoining the architectural structures

to the west from it.

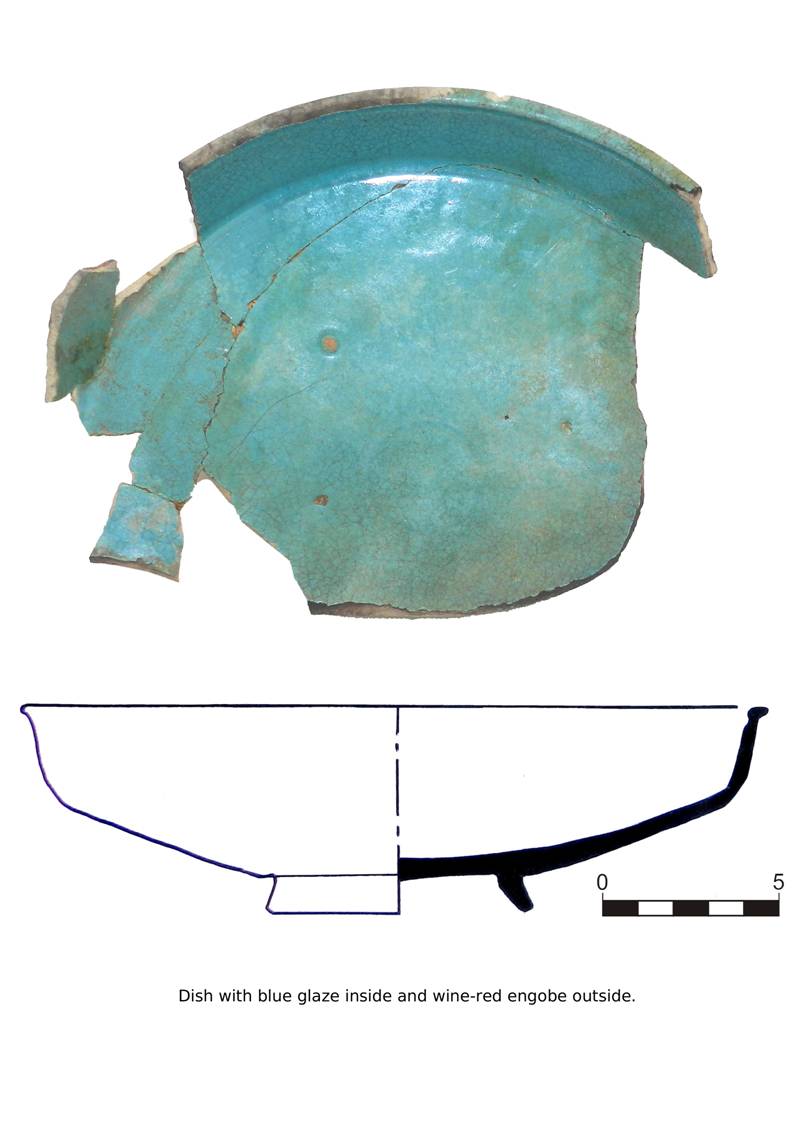

The finds gathered from the horizon uncovered by the excavations mainly

consist of glazed turquoise pottery sherds and fragments of non-glazed

pottery with red engobe. These features date the materials to the pre-Mongol

times.

From the debris in the western part of the dig were recovered several

pits and some small strata with pottery dating to the times of deep

social and economic stagnation in the 1st half of the XVIII AD as well

as several poorly preserved burials. The skeletons found there went

to pieces, and the numerous women’s decorations were scattered

all around. These burials interfered with the archaeological strata

of XII–beg. XIII AD, destroying them in several ways. The bricks

belonging to the earlier building period were taken off to edge the

graves which were shallow enough for the water to penetrate through

the holes dug by rodents.

The S–N orientation orientation of the burials, their poor order

and small depth (1-1,3 m) suggest a date in the Mongol times or soon

after that.

|

|

|

| Plate 3: central dig, western part in the foreground. |

|

|

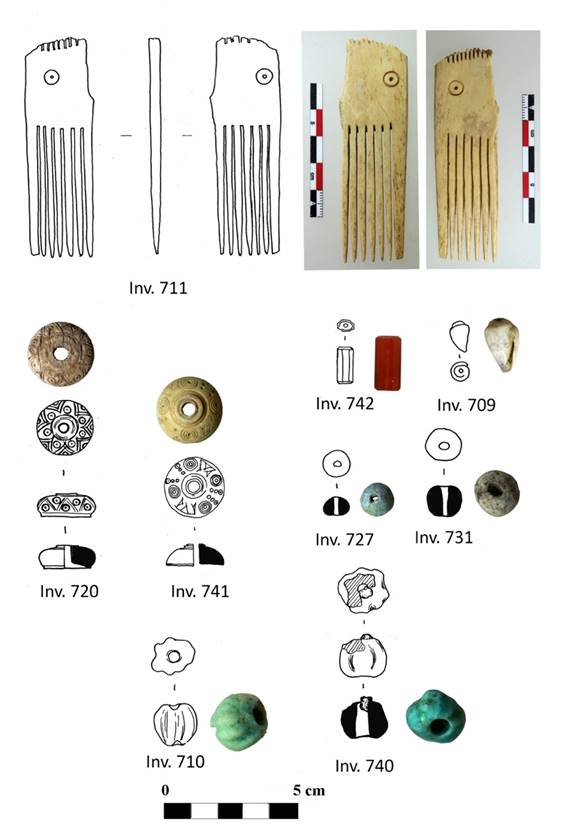

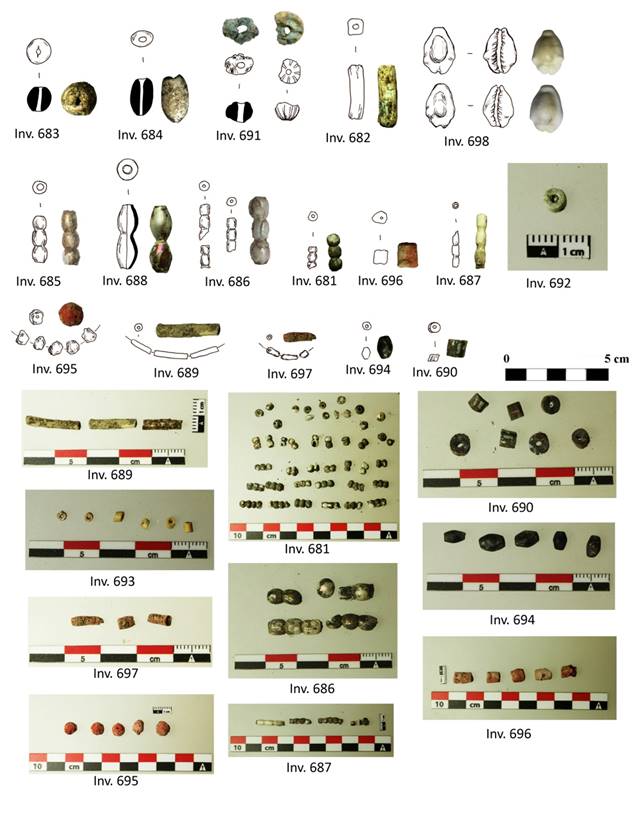

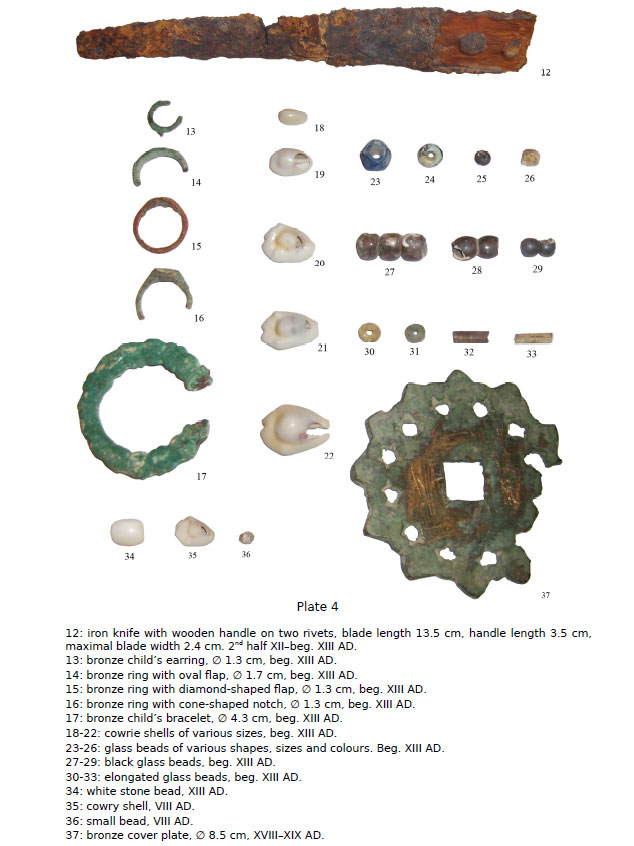

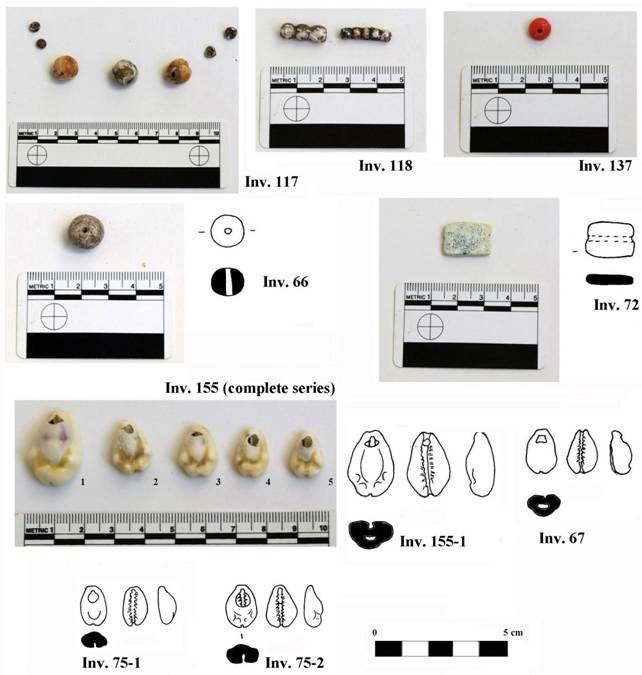

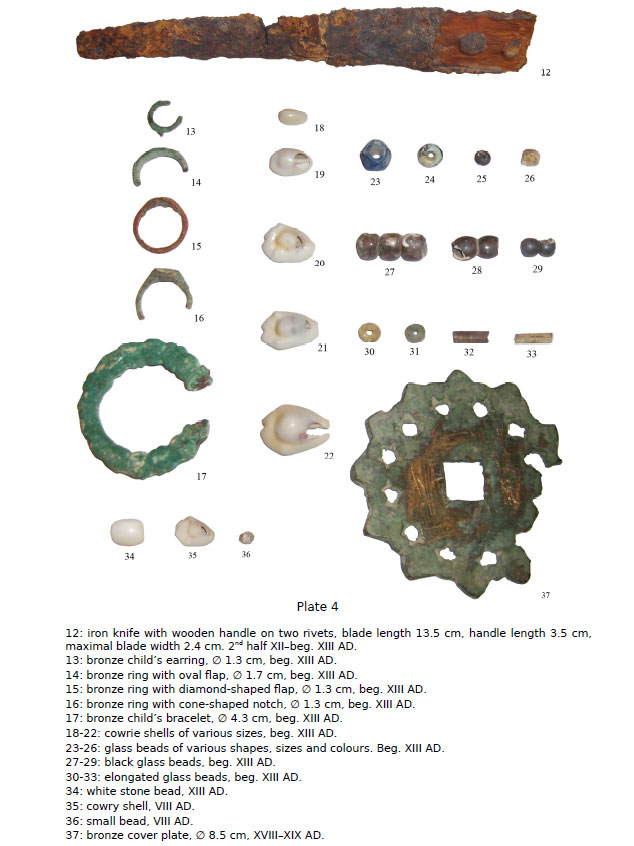

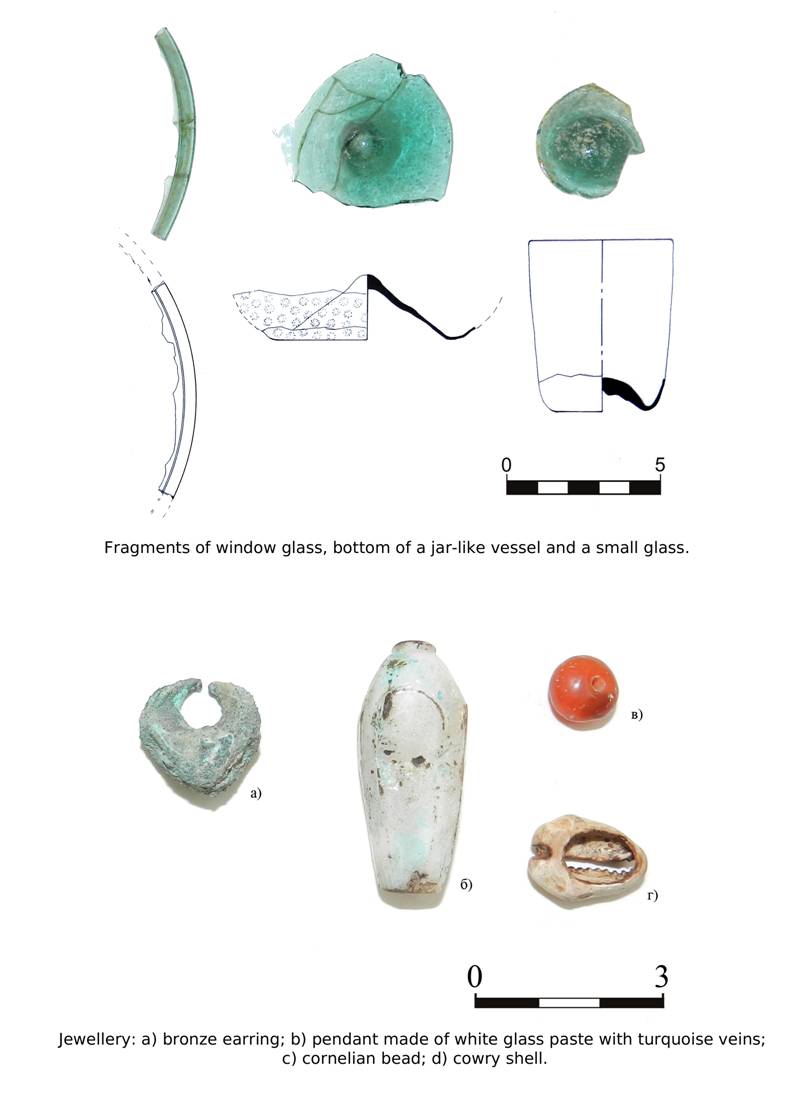

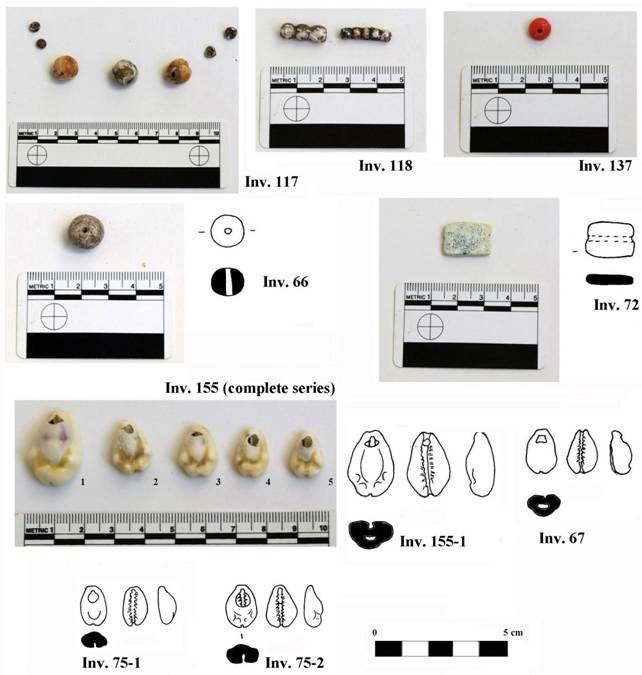

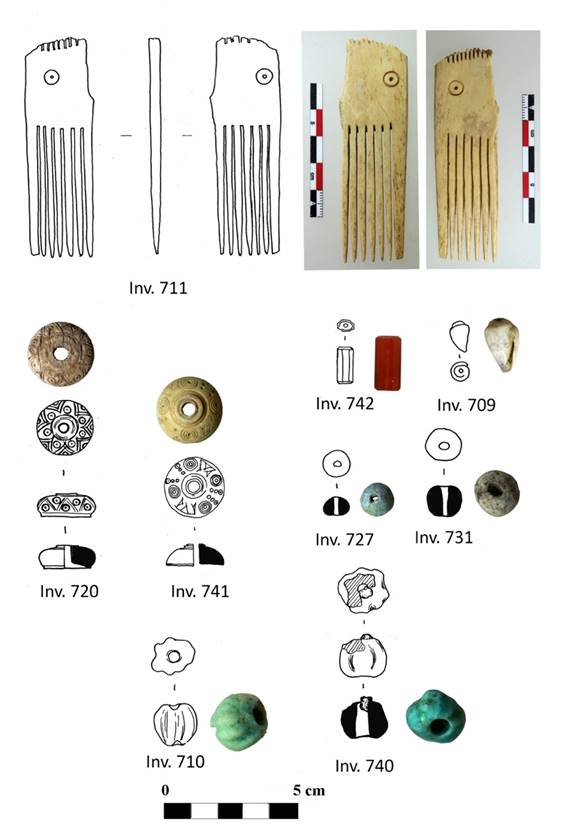

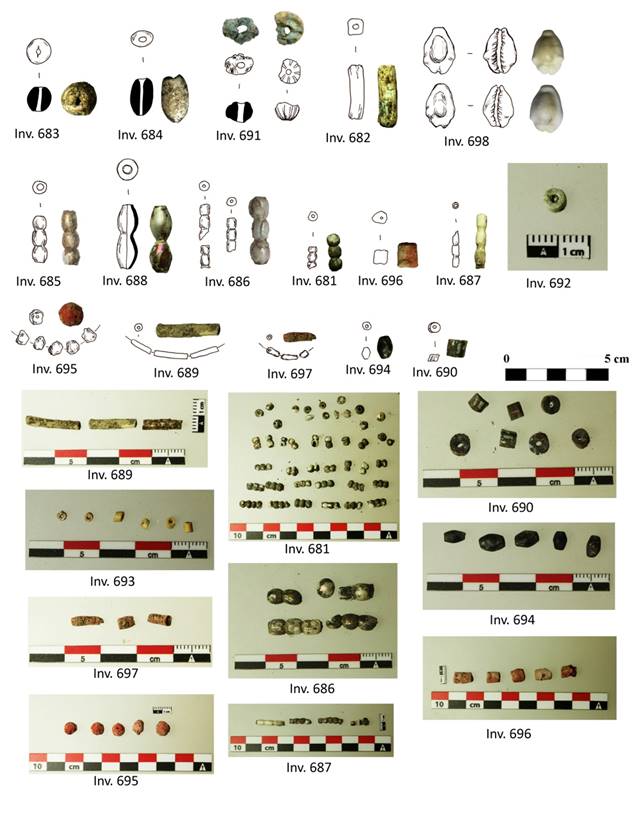

The finds from the central dig can be divided into two main categories:

pottery sherds testifying to its late squatter occupation, and a substantial

number of decorations from the female burials. The latter include beads

of various shapes made of glass of various colours: blue, dark blue,

black, yellowish, greenish, and turquoise, as well as of Cowries small

and large, cornelian, fruit stones, and bones.

One more group of decorations consists of bronze items: finger rings

of alike shapes and sizes, rod-like bracelets, fragments of earrings,

and small bells sewn upon women’s and child’s dress.

To the same stratum belongs the fragment of a bronze spoon and several

iron items probably coming from men’s burials – belt buckle,

finger ring, knife blade, etc.

It should be noted that among these decorations there were no items

made of precious metals or stones, which fact reveals the average, or

below average welfare of their owners. It is also noteworthy that a

traditional Muslim burial should not contain any women’s decorations

or men’s personal belongings. Perhaps we have here the evidence

of sedentarisation of the Turkic peoples who were less thorough in following

the rules of Islam, especially in the countryside where the masses of

the nomads were settling down.

It can therefore be argued that the site of Vardanze was in XII–beg.

XIII AD a rural settlement rather than an urban centre.

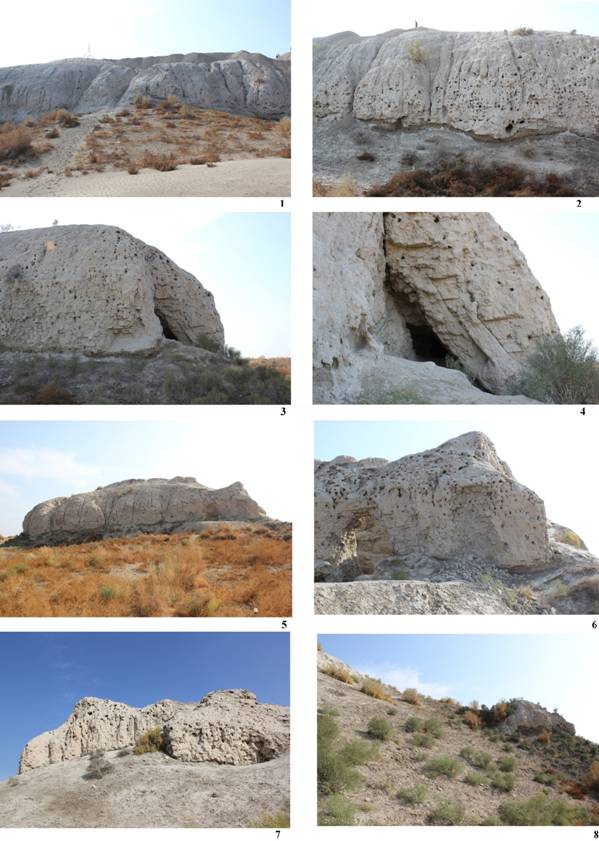

Trench 2 is situated in the western corner of the site,

by the junction of the N–W and S–W walls. Before the excavations

in this place was a large natural pit ca. 3,40 m deep, around which

were visible the remains of a main fortification wall with a breach

towards the north. It was natural to assume here a corner tower.

|

|

|

| Plate 4: western corner of the citadel before

the excavations. |

|

|

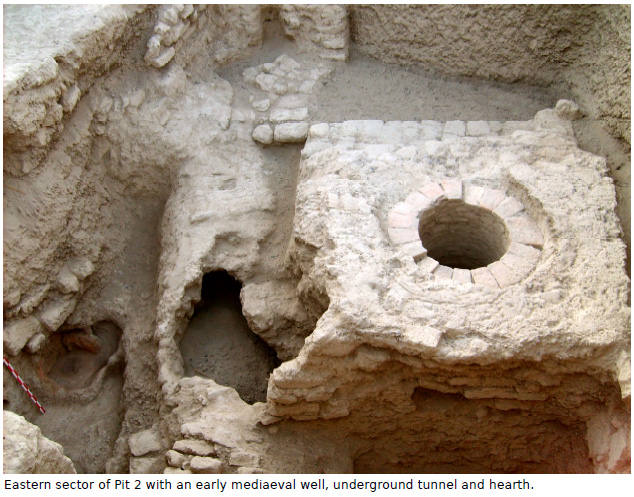

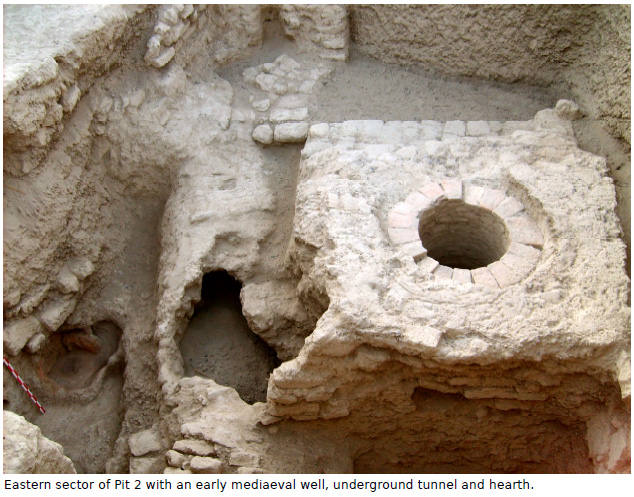

The top stratum in this sector appeared to be a debris of collapsed

constructions, fragments of sun-dried bricks and sand down to the depth

of 2,5 m. The pottery sherds from this stratum testified that from XII

AD to XIX AD the remains of the tower served as a shelter to random

occupants.

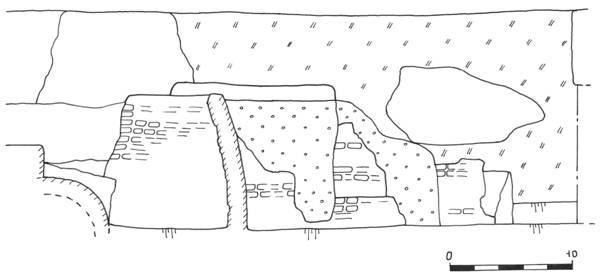

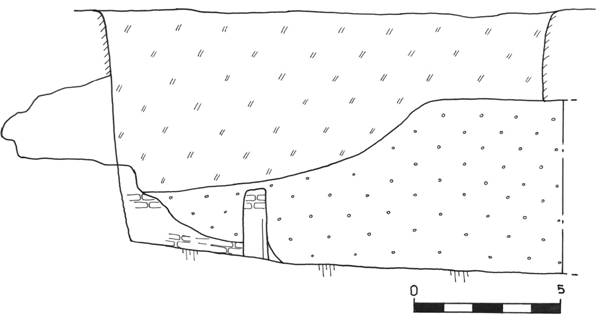

Lower down, at depth 5,8 m were revealed two parallel main walls built

of sun-dried brick with traces of plaster. Each wall is 1,9 m wide,

preserved up to 2,7 m of height. The space 2,6 m wide between the walls

was full of broken brick, crushed stone and sand, and contained fragments

of thick-walled moulded pots, jugs and pitchers. Given the dark brown

and reddish engobe on the cheeks of the pots and the cuff-like shape

of the rim of one jar, the ceramic complex can be dated to V–VI

AD.

Such dating testifies to the fact that the two walls fringing the N–W

edge of the citadel are the remains of its earliest fortifications.

Filling the space between two walls with gravel is a building technique

which finds its parallel in the fortification of Ramitan and other Early

Mediaeval sites in the Bukhara oasis. Later on, probably near the time

of the Arab conquest, all walls were enforced by a jacket made of sun-dried

bricks 42 × 21 × 12 cm, as a result of which the initial

wall width of 6,4 m reached ca.11 m.

|

|

|

| Plate 5: brickwork of the outside jacket of

the main walls. |

|

. |

Plate 6: excavated western corner of the citadel

The eastern side of the corridor formed by the two walls has two passages,

one in the N–E part (2,1 m high and 1,15 m wide), the other in

the S–W part (1,05 m high and 0,65 m wide). This last one was

probably made by the people hiding here during the times of troubles.

In the S–W the corridor inside the walls reaches the transversal

outside wall of the citadel, in the N–E it extends further, going

parallel to the outside N–W wall. For the safety reasons, the

investigations were stopped after 9 linear metres of the corridor were

uncovered.

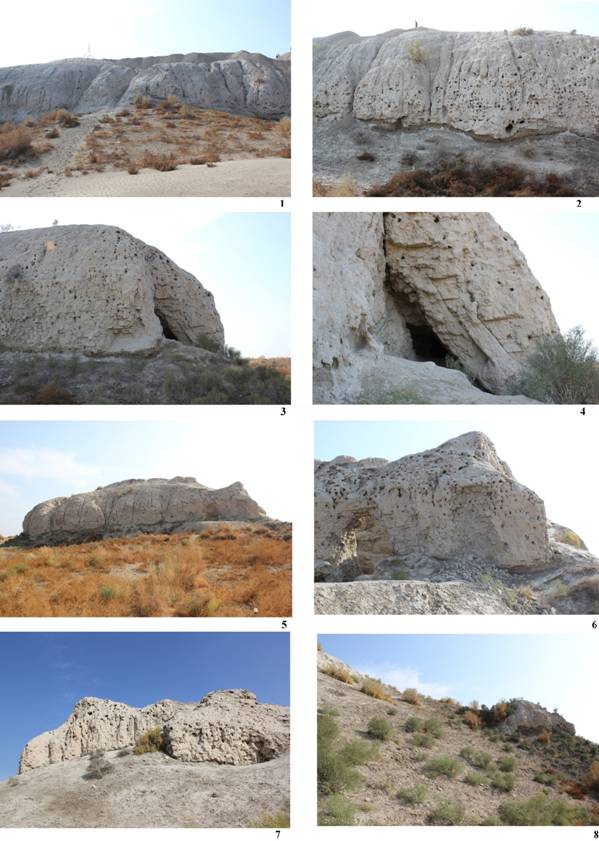

To summarise, it can be stated that the end of the prosperity at Wardana

is associated with the Arab invasion. In IX–XI AD the citadel

was not regularly inhabited, and it is only in the period immediately

preceding the Mongol invasion that another occupational phase can be

traced. With the Mongols coming, the site must have been destroyed and

the citadel became a graveyard. At later times only squatter occupation

can be attested, with one large influx during the crisis that happened

in the 1st half of the XVIII AD when masses of people were

seeking refuge at places inaccessible for the nomads.

|

|

|

Plate 7: view of the shahristan from the top

of the citadel, facing S–E. |

|

|

Plan for 2010

The excavations will be continued in the central part on top of the

citadel since it is assumed that the palace could have stood here.

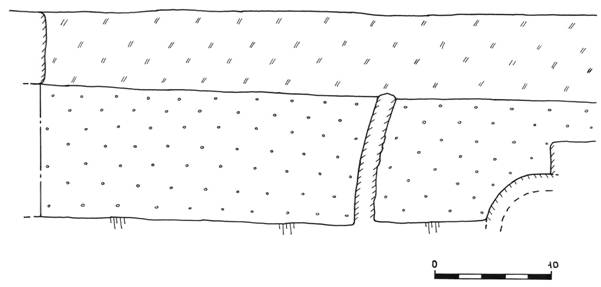

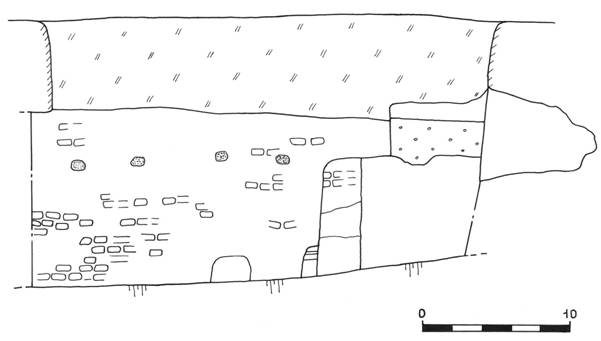

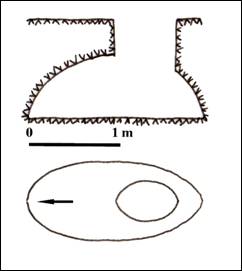

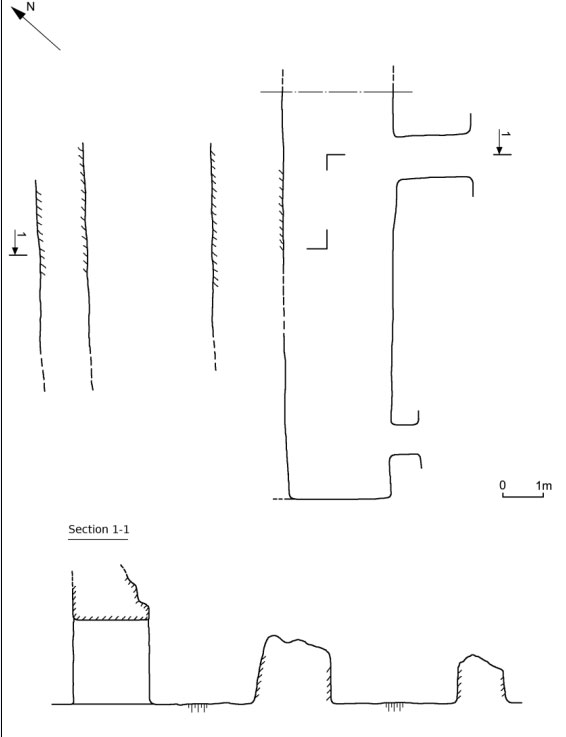

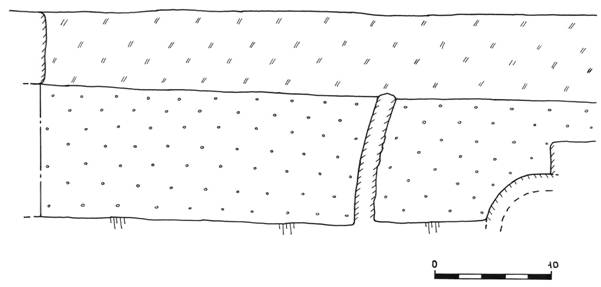

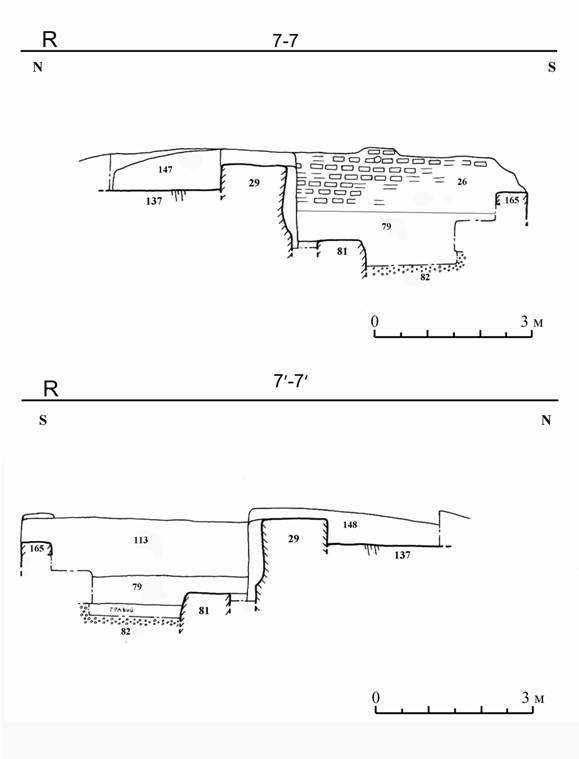

Cross-Section: Remains of the fortification system near

the foundation of the S-W tower.

Building structures and remains of a main fortification

wall in the central part of the citadel.

Building structures and remains of a main fortification

wall in the central part of the citadel.

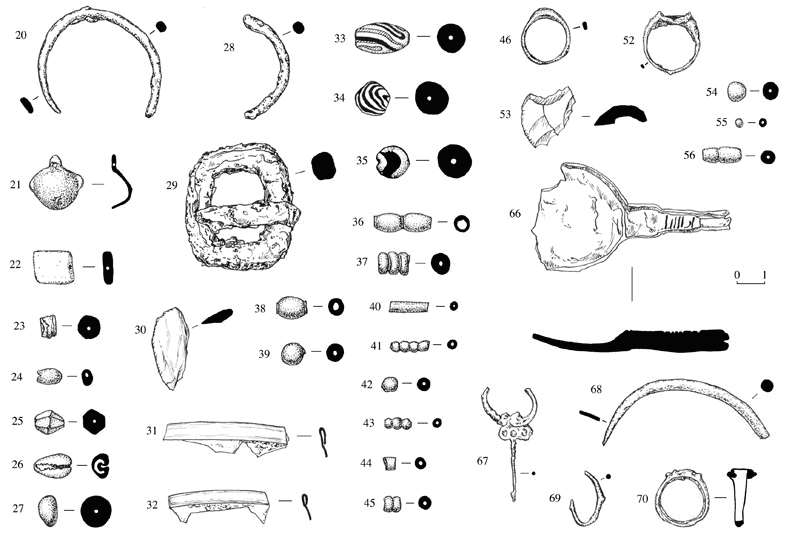

Overview of finds and captions to sketches

Citadel of Wardana (Vardanze-tepa)

investigated by

Excavations Report, Autumn 2011

The site of Vardanze (anc. Wardana) is situated on the NE edge of the Bukhara

oasis, on the border with the nomadic steppe. In the times of the late Antiquity

and the Early Middle Ages the area was watered by one of the channels of the

R. Zarafshan, it was covered with vegetation and was abundant in game. In V– VI AD the site was the seat of the rulers of the NE part of the oasis, Wardan

Khudas. Until mid-XIX AD Vardanzeh was an important handicraft and trade

centre on the trade route connecting Central Asia through Kwarizm with the

Caucasus and Eastern Europe. The aridisation that started in XIX AD led to the collapse of economic and social life and complete desolation.

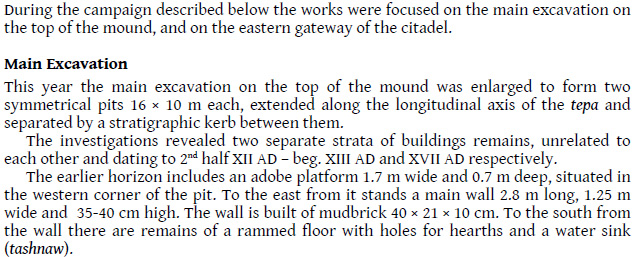

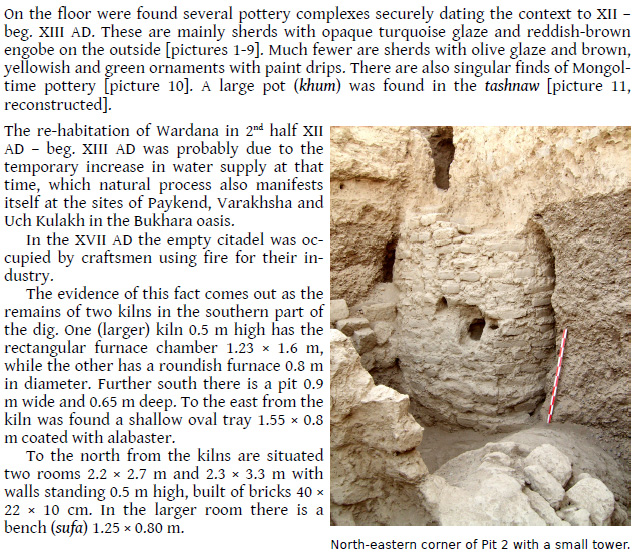

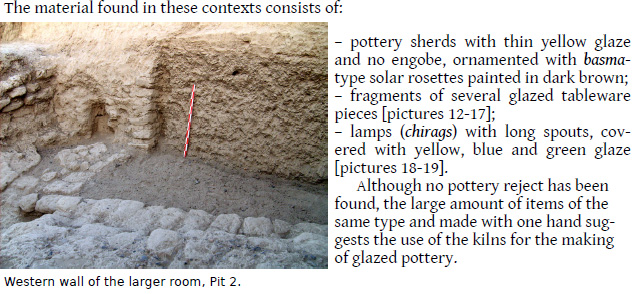

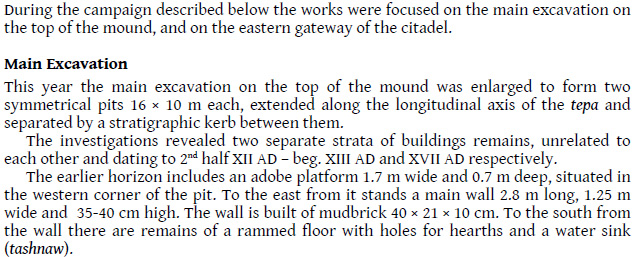

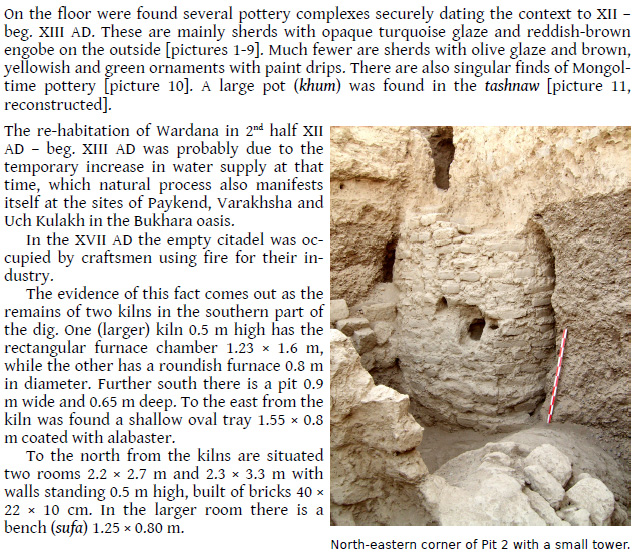

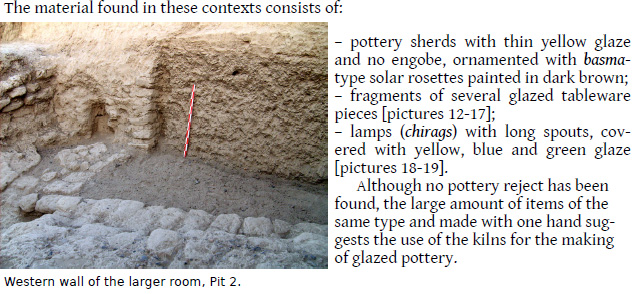

During this campaign all works were centred at the main excavation on the top

of the mound, extending the existing excavation in SW direction. The twometre-

wide stratigraphic kerb dividing the previous trenches 1 and 2 was

demolished, and the remains of a pre-Mongol building dating to the last occupa!

tional period of the citadel (end XII – beg. XIII AD) were removed.

The next stratum consisted of poorly preserved remains of mudbrick walls

0.30–0.5 m high, standing on a massive adobe basis. Beneath the basis was

revealed a thick and sterile gravel bed marking the gap between the occupation

in IX–XI AD, and the revival of the citadel on the turn of XIII AD.

This last feature is paralleled by the same phenomena observed at the sites

of Paykend and Varakhsha, where it is explained by an influx of peasants from

the central parts of the oasis, trying to escape the increased tax burden under

the last Qarakhanids and the Khwarizm Shahs.

To this might be added the data of the primary sources, telling us about the

large-scale activities of the Khwarizm Shah Muhammad, who on the eve of the

clash of the Khwarizmian and the Mongol empires ordered to strengthen the

city walls countrywide in the end of the second decade of XIII AD.

The excavation measuring 11 m E–W, 8 m N–S reached the depth of 5 m. A wall

3.05 m high divides it into two uneven parts, the eastern one 3"3 m and the

western one 6"6 m. The wall made of sun-dried bricks 42"25"11 cm is

oriented N–S, and goes beyond the excavation's edge. At 2.15 m from the floor

level there are four oval pockets for the roof beams, 20 cm in diameter and 20

cm deep.

In the southern part of the wall, at the floor level were revealed the remains

of a rectangular hearth with a semicircular top, 0.7 m wide and inserted 0.45 m

deep into the wall.

Beneath the gravel bed mentioned above were found the remains of two

rooms built of sun-dried bricks 32"22"11 cm and having their doorways to the north. Both rooms are extended to the south and go beyond the edge of the

excavation. Room 1 is 1.95 m wide with the western wall standing 2 m high and

the eastern wall 1.55 m high. Room 2 is 2.3 m wide, with the walls 1.05 m and

1.85 m respectively.

The SW corner showed the remains of a large cesspit 3.1 m wide, going

down from the level of the 2nd half XII – beg. XIII AD. The pit was filled with

ashes testifying to a big fire in the beginning of XIII AD, and with fragments of

glazed and non-glazed pottery, metal- and glasswork badly damaged with fire.

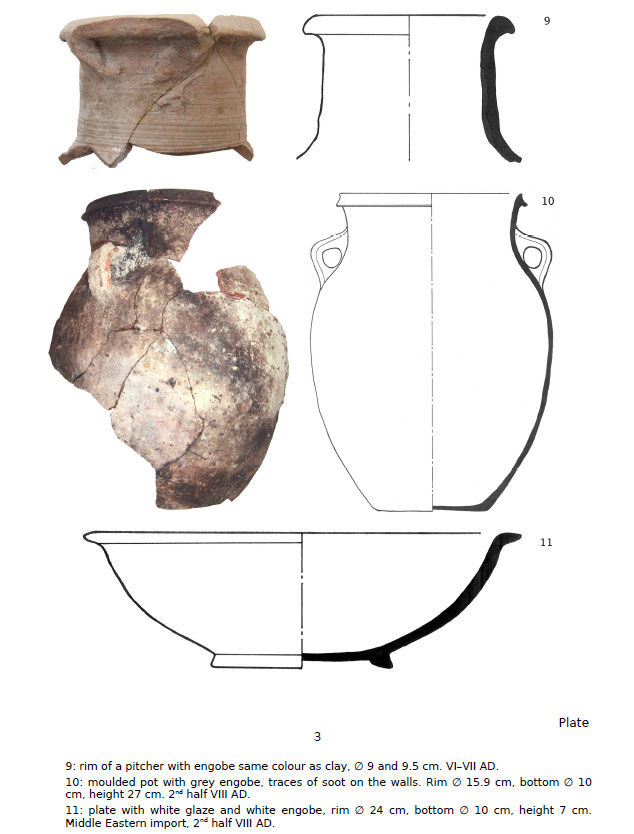

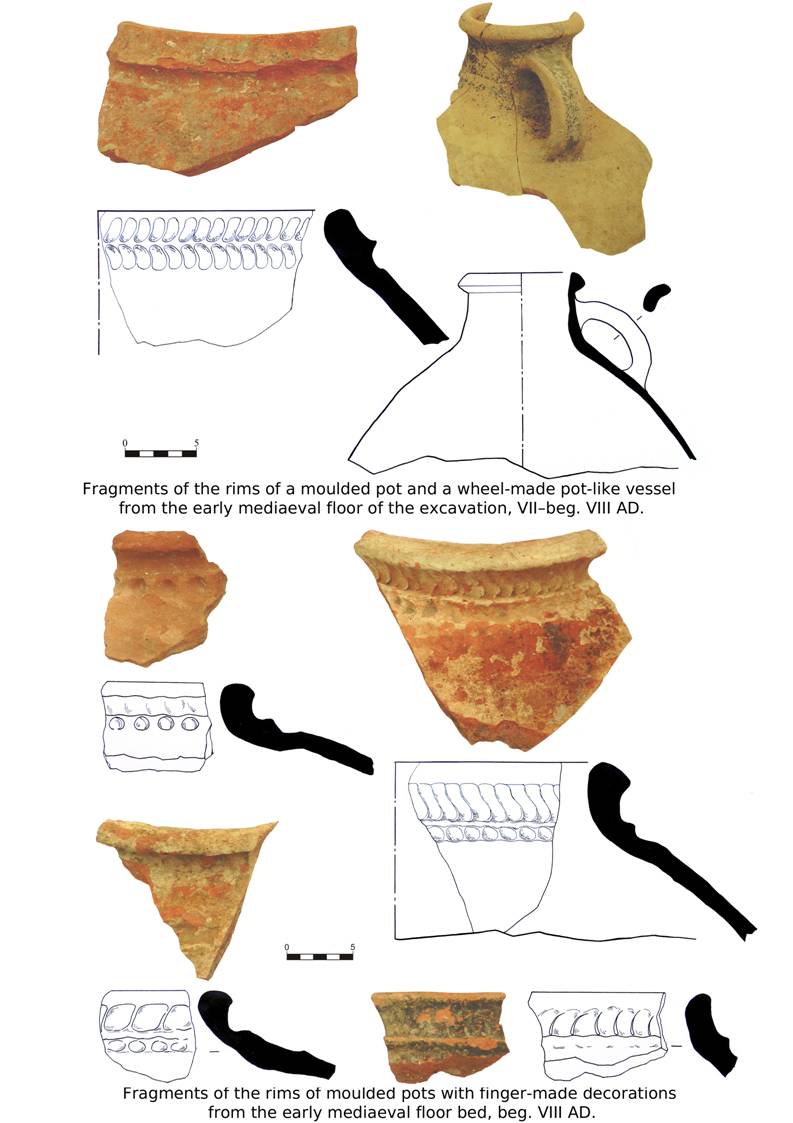

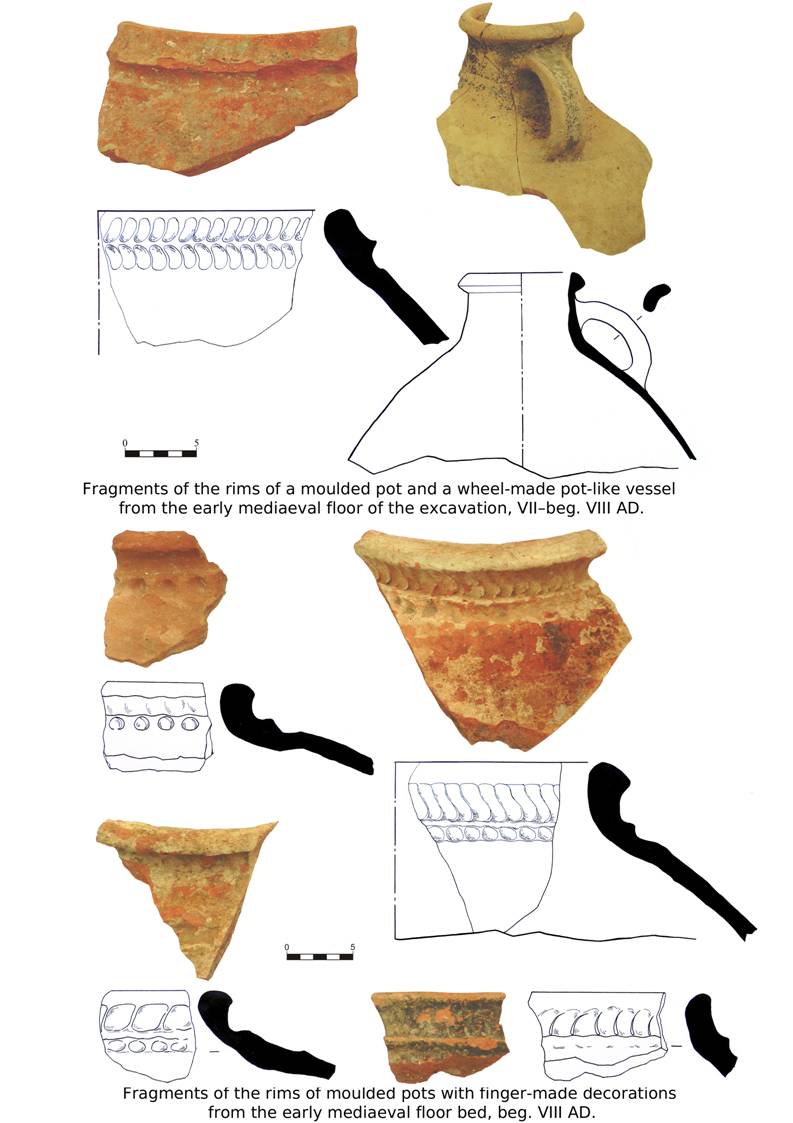

The material found on the early mediaeval floor consisted of fragments of

moulded pots with characteristic finger-made decorations, and a large wheelmade

pot with black engobe on the rim. These finds securely date the floor to

VII – beg. VIII AD.

The most interesting architectural detail revealed was an underground

tunnel going N–S and intersecting with the previously discovered tunnel

oriented E–W. The tunnel declines to the north and continues under the floor

towards the main gate of the citadel.

Thus it can be observed that, some time after the death of Wardan Khuda

and the destruction of the citadel, another occupational phase begins. It is

marked with rebuilt walls, construction of underground tunnels, raising the well

level, erection of a tower-like building, etc.

Initially this had been the citadel's courtyard with the remains of buildings

in its southern sector and a well in the middle of the courtyard.

Exploring this particular context was particularly diffcult because of the

struggle through the gravel filling, with three or four grade levels of removing

the earth from the depth of ca. 5 m.

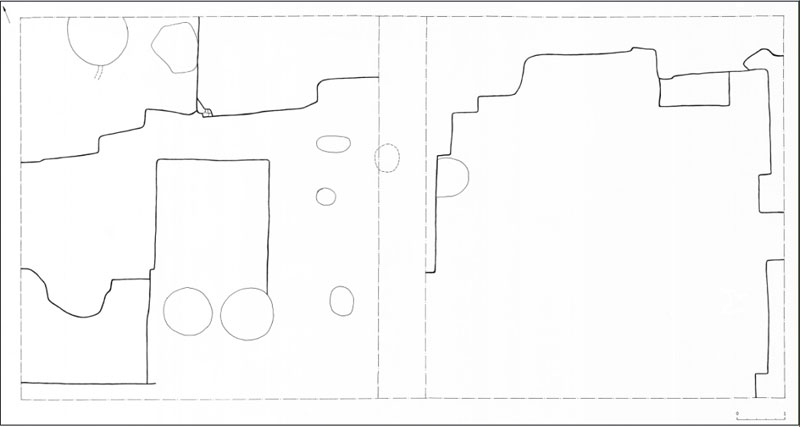

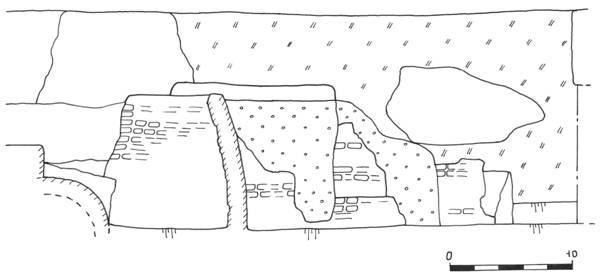

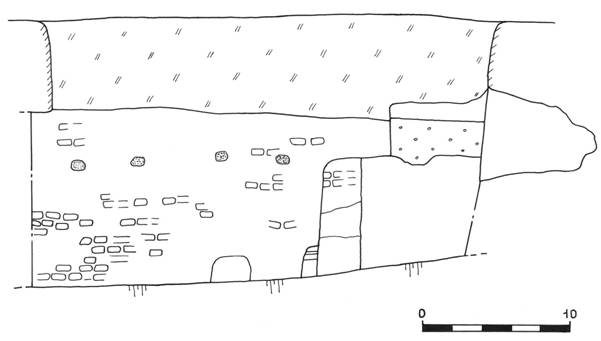

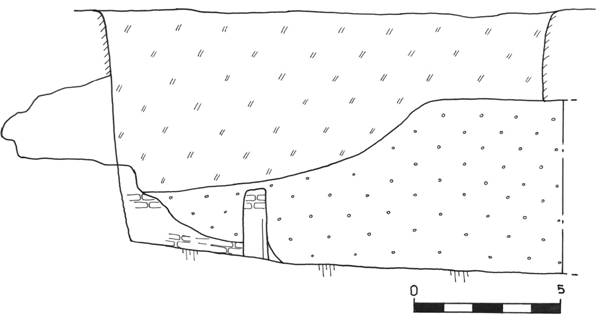

General view of the excavation facing west.

Western part of the excavation. Lateral wall with beam pockets and hearth.

Western part of the excavation. Hearth on the eastern wall at floor level.

Western part of the excavation. Northern wall with gravel bed.

Western part of the excavation. Western wall with loess filling.

Southern wall with the remains of two rooms and a cesspit.

Western part of the excavation. Two rooms and a cesspit in the southern sector.

Western part of the excavation. Doorpost at the entrance into Room 2.

Eastern part of the excavation facing west.

Eastern part of the excavation. Northern wall with filling.

Eastern part of the excavation. Southern wall with the turn of the wall.

Raised platform of the well and the underground tunnel going N–S.

Eastern part of the excavation. Well platform and underground tunnel.

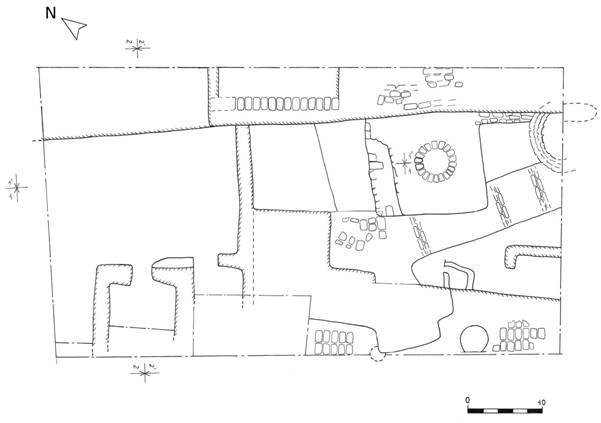

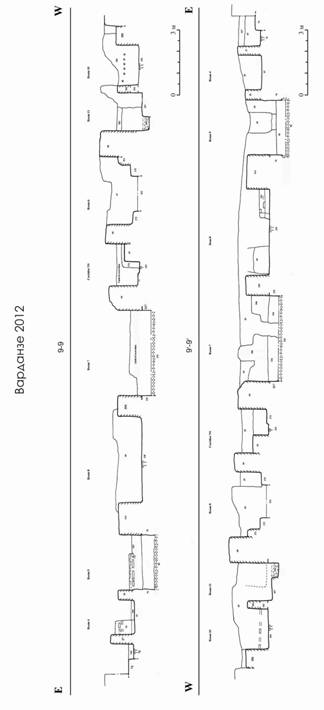

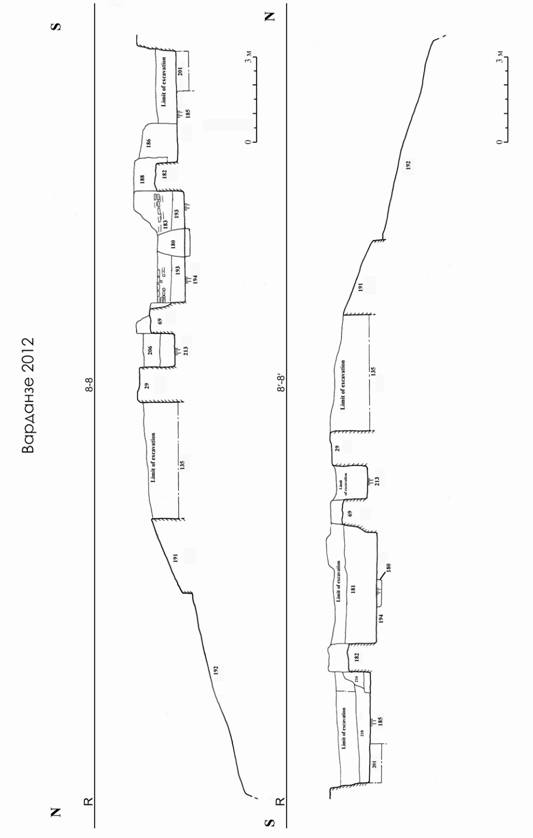

Ground plan of the excavation in 2011.

Section 1–1

Section 1'–1'

Section 2–2

Section 2'–2'

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Society for the Exploration of EurAsia

REPORT ON THE FOURTH ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION AT VARDANZE (ANCIENT VARDĀNA),

BY THE WEST SOGDIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION

(2012)

The Society for the

Exploration of EurAsia

REPORT

ON THE FOURTH ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION AT VARDANZE (ANCIENT VARDĀNA),

BY

THE WEST SOGDIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION

(2012)

Silvia Pozzi

With contributions by J. Mirzaahmedov,

Sh. Adylov

and the drawings by S.

Mirzaahmedov and M. Sultanova

January 2013

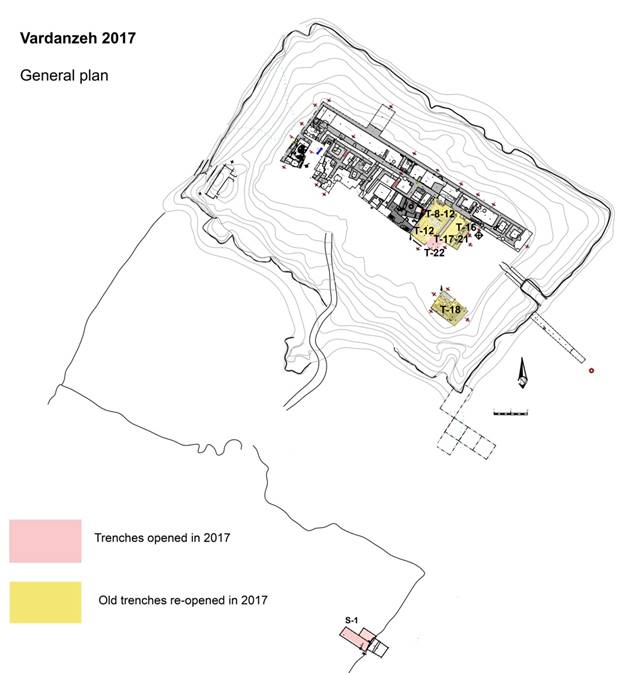

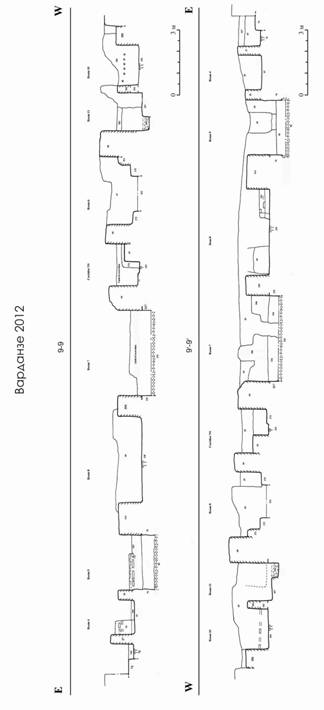

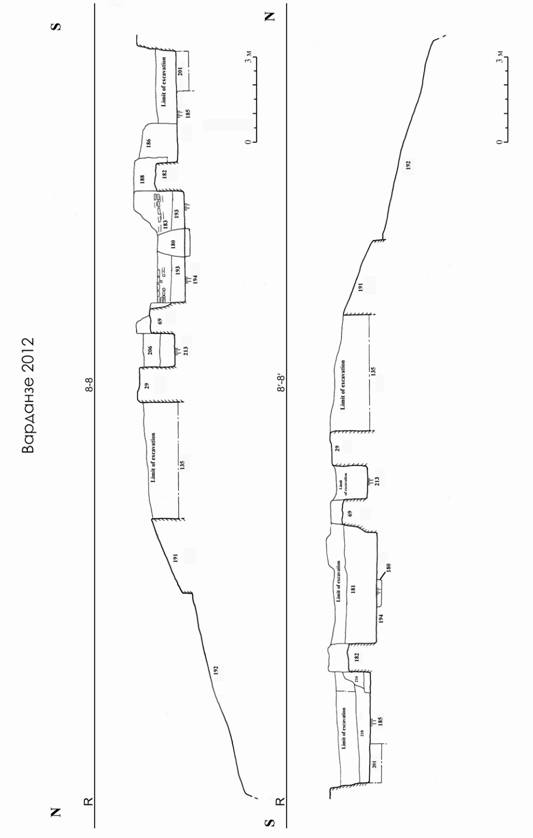

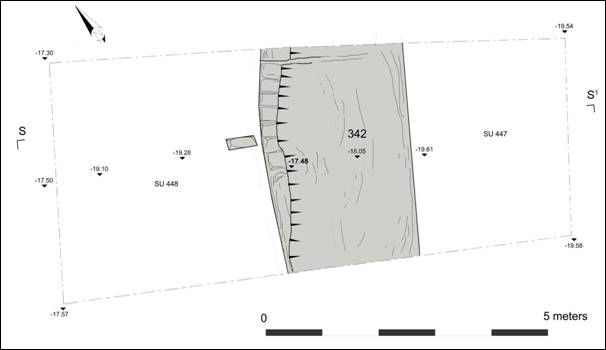

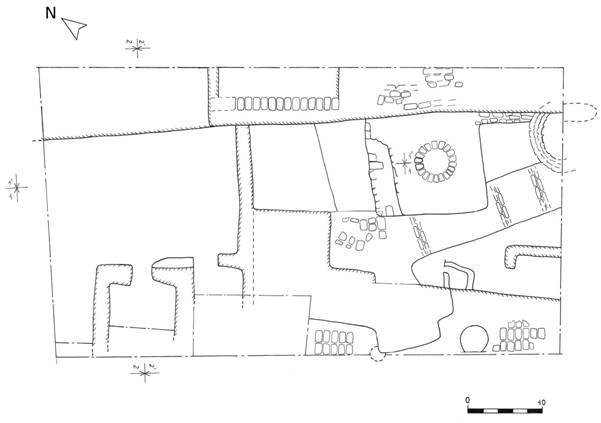

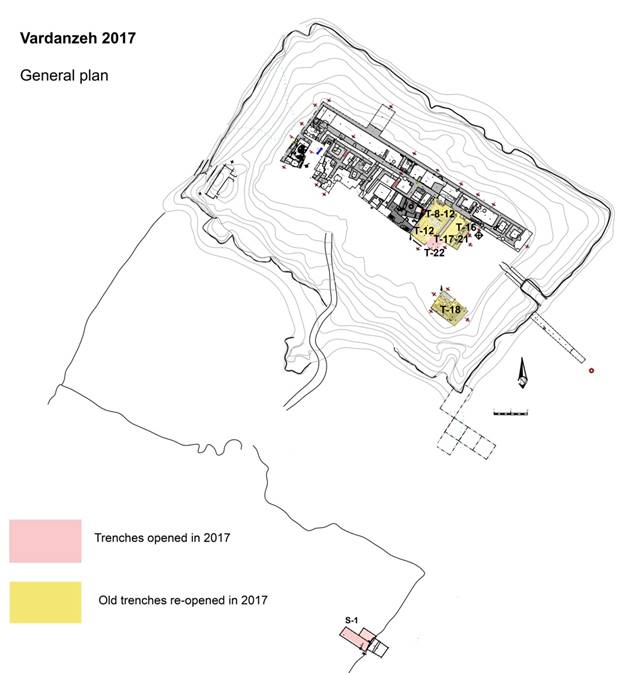

Preliminary remarks

The

archaeological investigations at the citadel of Vardanze (ancient Vardāna),

capital of a small

Early Mediaeval principality located on the

borderline of the Bukhara oasis, were carried out between September, 29 and

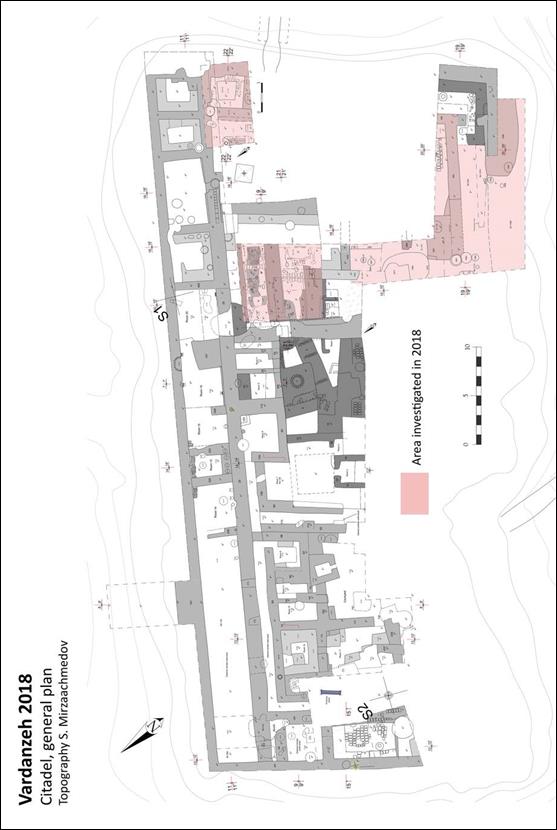

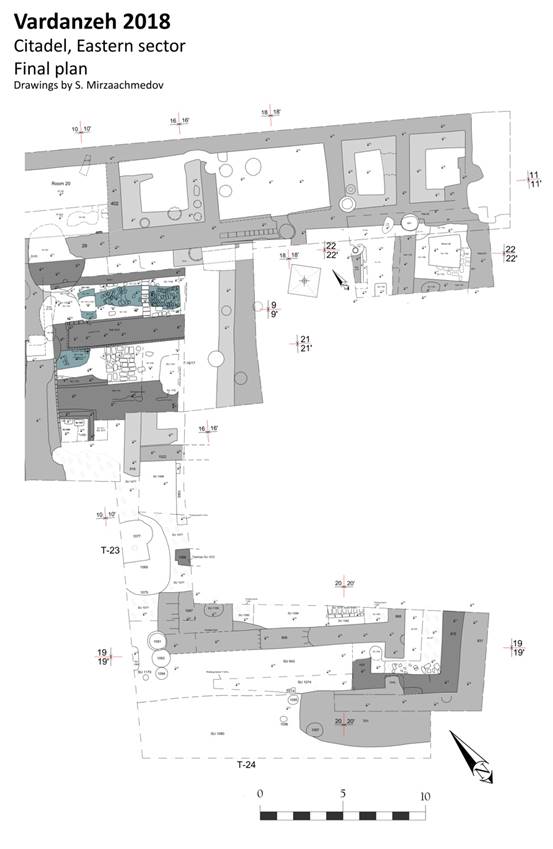

November, 5, 2012. The main objective of this campaign was an extensive

investigation of the building phase immediately subsequent to the one excavated

in 2011. For this purpose the fieldwork

focused on the area north of the previously excavated sectors (trenches 1-2),

where three contiguous trenches (named trench 3, 4, 5) were laid one by

one without separating partitions. In addition, Trench 2, where the

upper strata had been investigated in the past years, was deepened and several

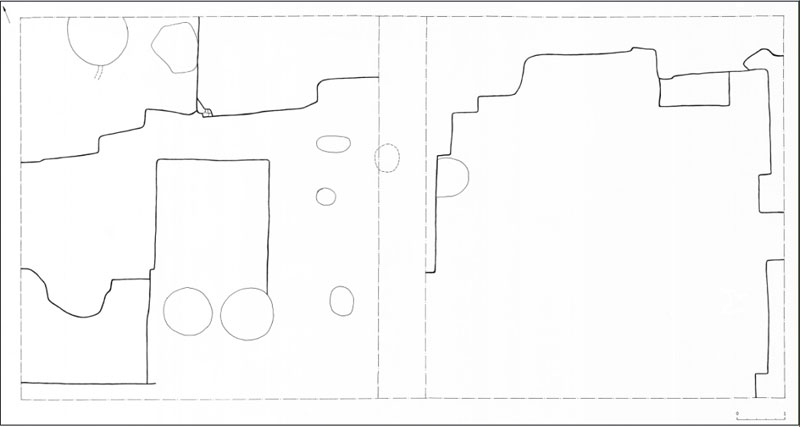

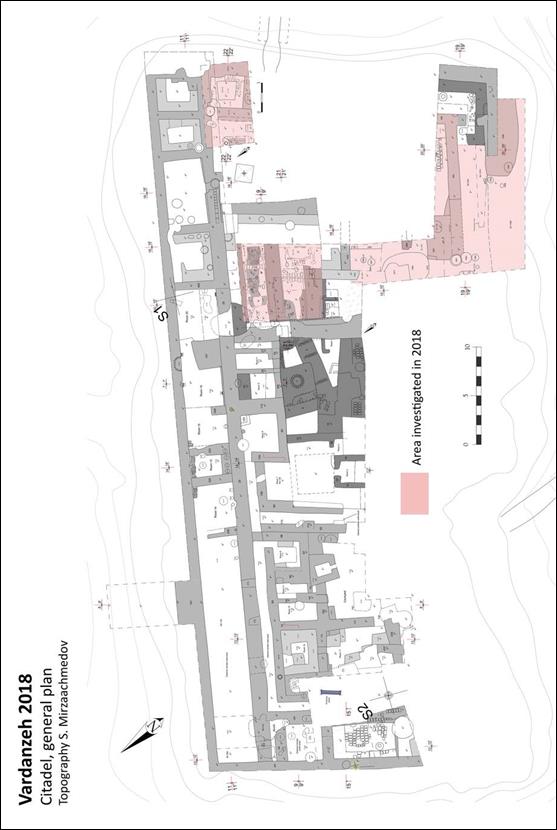

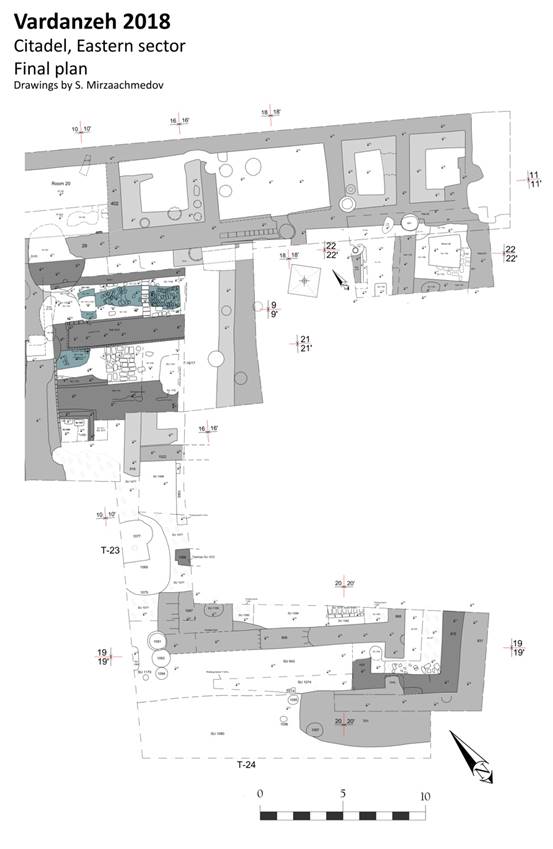

architectural structures were completely exposed at the total area of 532 m2. Besides the excavation, a further objective of the 2012 field season was to

update the topographic maps, showing both old and new trenches.

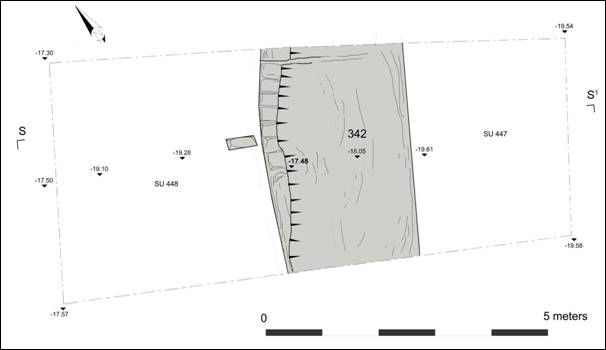

Note

All the

excavated stratigraphic units (walls, floors, layers, fillings, etc.) were

registered with the abbreviation SU (stratigraphic unit) and assigned specific

numbers. However, in this report the walls are indicated without the

abbreviation in order to facilitate the reading. The dimensions of the walls,

when given, appear in this order: thickness, length, and preserved height (H).

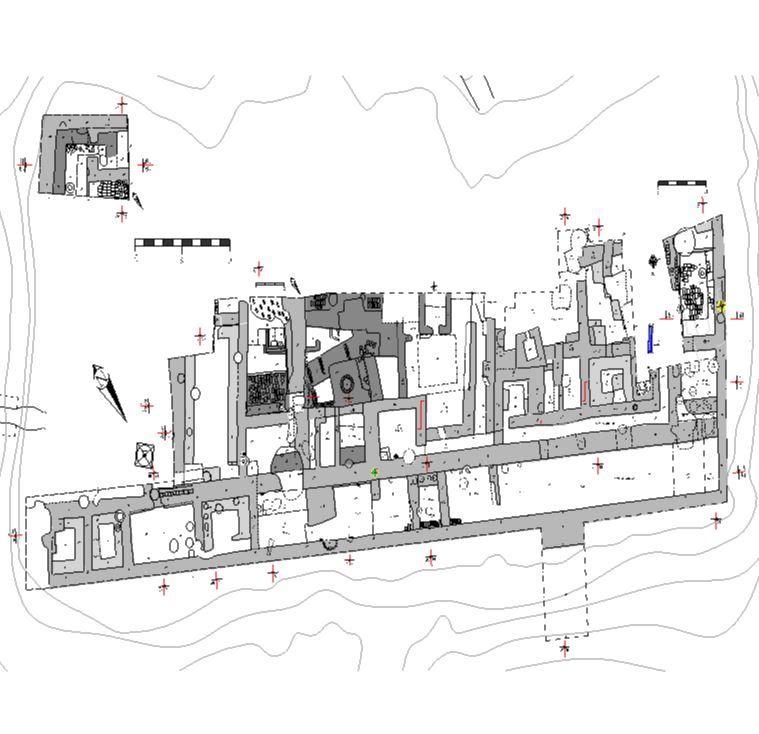

Excavation

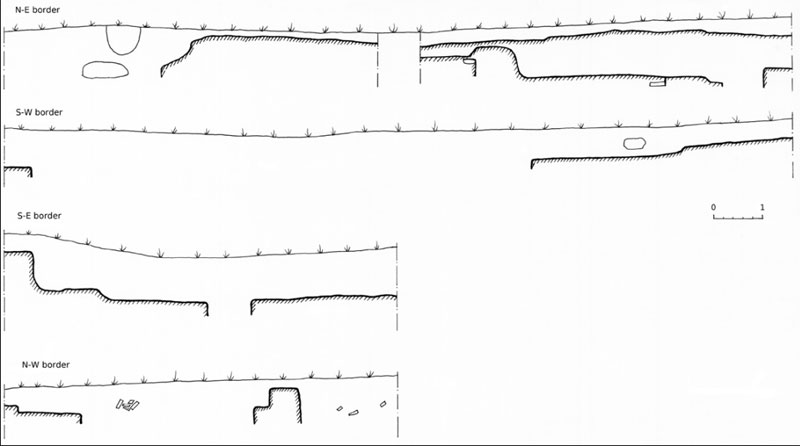

Monumental defensive

system

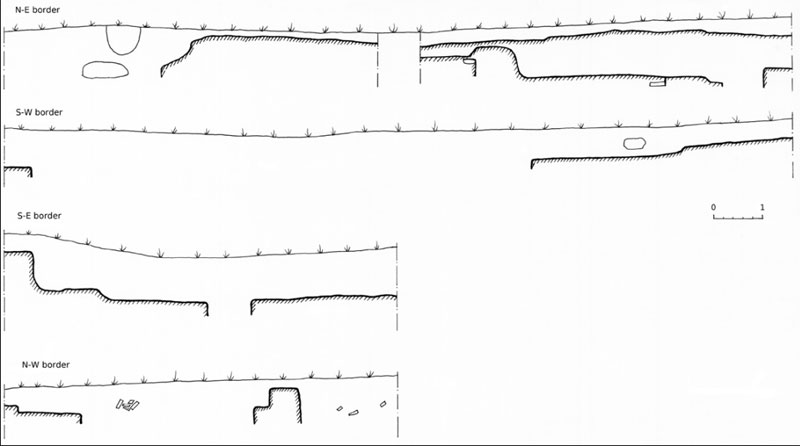

The

most intriguing architectural feature discovered this year is a monumental wall

system enclosing the northern side of the residential area (Figg. 2, 4).

At the present state of excavation it consists of two parallel walls running

along the longitudinal axis of the tepa (E–W). The external wall is 191,

2.7 m thick, the widest wall found so far, and it is built of large mudbricks

(43×26×12 cm). Its southern face is still well plastered and has been excavated

up to a length of 10 m (Figg. 11, 12). The upper side of the wall lowers

towards the north, following the eroded profile of the tepa. The

northern extension of trench 5, which was aimed at investigating the width of

this wall, revealed several layers of rammed heart (pakhsa). The layers of pakhsa

(each layer is 14 cm thick), which alternate irregularly with rows of mudbricks,

have been found only on the northern face of the wall. The pakhsa seems to

extend to the limits of the citadel, but the structure is disturbed by a wide

rubbish dump (SU 199) filled with fragments of fired bricks, a grave (SU 202)

and a hole (SU 203) containing fragments of glazed pottery (18th-19th centuries AD).

South

of wall 191, at the distance of 4 m, there is wall 29, which is 1.30 m thick.

Both walls run parallel to each other for 35 m (Fig. 10). This wall,

found at 10-15 cm beneath the surface, is built of mudbricks measuring 42×25×12

cm and it is intersected by two later graves (SU 127-128) in its western section.

Its southern side represents the limit of the dwelling area. It was exposed for

its entire length and height, down to the floor levels (-2.60, -2.90 m). The

northern side was partially exposed, so it is unclear whether the space between

the two parallel walls had been used as a corridor. The western part, belonging

to trench 5, was excavated down to one metre from the top of the wall but no associated

floors were found. The only rammed earth floor found (SU 137, -2.65 m) is

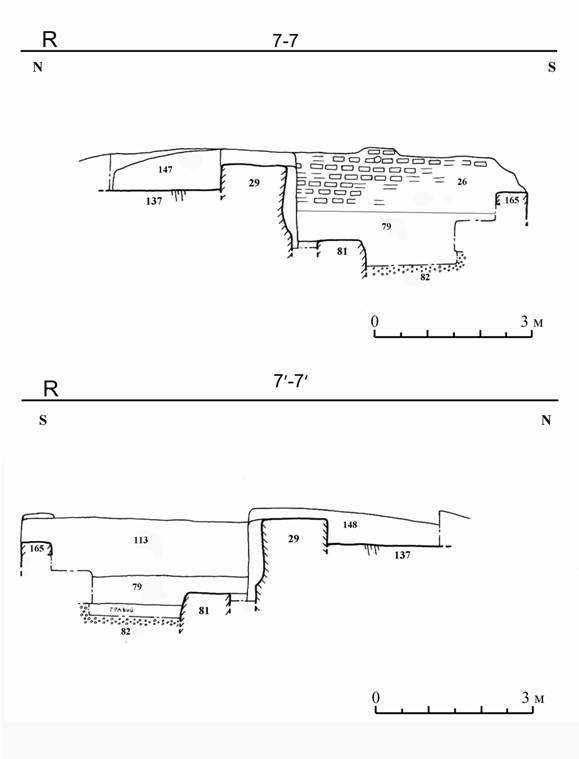

located north of wall 29, close to the eastern edge of the excavation field.

Three fragments of oinochoe-like juglet rims, dating to 7th-8th cent. AD, were found on

this floor. A mudbrick structure (SU 147) leaning on the northern face of wall

29 probably belongs to this context as well (Fig. 7). The masonry is

clearly visible, but the limits of the structure that slopes down northwards

remain unclear. Further investigation could demonstrate if this is a wall

reinforcement. The remaining area north of wall 29, excavated only to a depth

of 20 cm, has several rows of aligned mudbricks laid against the same wall (Fig.

8). There are several holes cut through these mudbricks (for storage

jars?), as well as cesspits (badrab) and water sinks (tashnau). An

isolated human skull was also found, buried several centimetres under the

surface. The jugs and the jars found in situ (on the spot) demonstrate

that this area was in use during the 12th century, although a

greenish glazed dish and a turquoise lamp (chirag) dating to the 18th century show some sporadic occupation in later periods.

Corridors EW and NS

The

dwelling area situated to the south from the perimeter wall 29 is divided into

two different but related sectors (eastern sector and western sector),

whose internal circulation is defined by a T-shaped system of corridors. The NS

corridor, 2 m wide and 4.5 m long, forms the proper division between the two

sectors and contains a bench (sufa) abutted to the eastern wall 64 (Fig.

9). Proceeding northward, this corridor intersects the EW corridor, while to

the south it opened probably into a big hall or a courtyard located to the east

of wall 64. The EW corridor (1.20 m wide) runs parallel to wall 29 and it has been

presently unearthed for a length of 22.5 m (Fig.

10). This corridor was originally connecting the two sectors, but was later

obstructed by two walls (131, 206). In particular, wall 131 (4.8 m long) was

built on the junction between the two corridors, closing the passage. At the

same time the NS corridor was narrowed by the building of two walls (62 and

174) abutted to wall 66. Thus, the function of the spaces was modified and

rooms 6 and 8 remained isolated. It is probable that from the beginning of the

8th century AD room 8 was definitely abandoned until its re-use in

the 12th century.

Eastern sector

Room 4

The room

measures 1.50x 3.80 m and the perimeter wall 29 constitutes its northern limit

(Fig. 13). The eastern wall (27) (4.3x0.43, H: 1.10 m) presents a

particular texture called ‘combined brickwork’ (mudbricks and pakhsa), frequent in the Early Medieval structures (Fig. 14).

In this case the masonry is made by rows of headers (mudbrick size: 40x23x9 cm)

separated one from another by layers of pakhsa 6-9 cm thick. The western wall

(26), measuring 3.8x0.43, H: 0.80 m, was built with the same technique, and presents

a more eroded surface, especially in its southern part. A round hole (Ø: 10

cm), probably built to provide ventilation, pierces the masonry in the upper

part. The massive wall 53 (60x110, H: 50 cm) connected to wall 26, represents

the southern limit of the room, where there is also an entrance. The cleaning

of a partially preserved mudbrick floor (SU 55, -2.50 m) revealed the presence

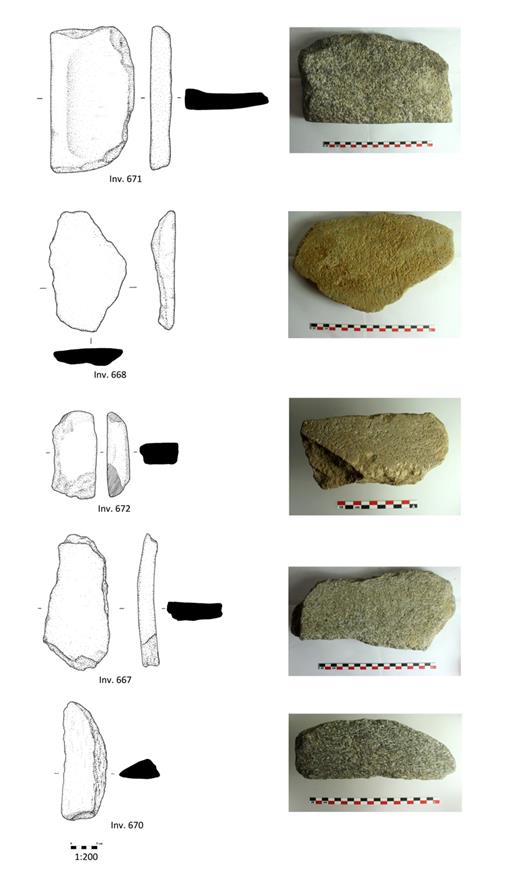

of pottery fragments dating to the 7th-8th centuries AD

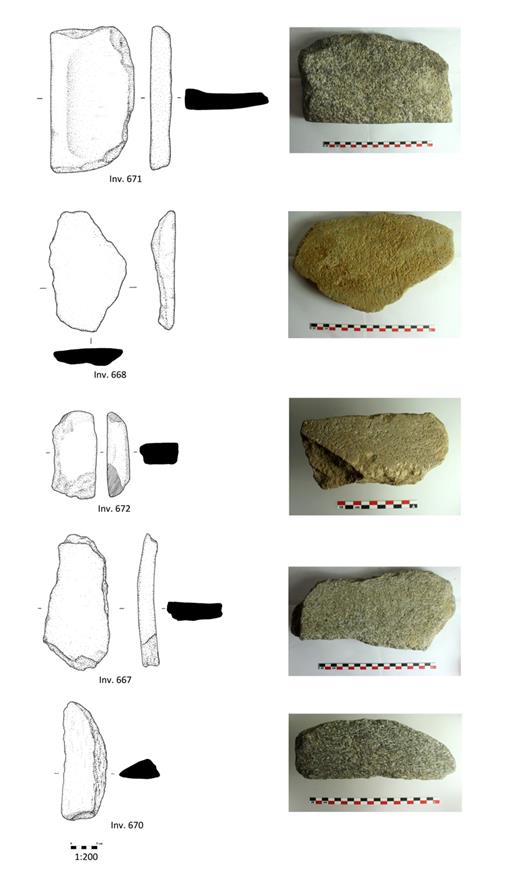

and of a schist millstone scattered in correspondence of the entrance. Another

wall (165) was detected under wall 53, demonstrating the existence of a

previous building phase. This wall was found also under room 9 and to the east of

wall 27 (Fig. 15). We can suppose therefore that in a previous phase

rooms 4 and 9 formed a large room, enclosed to the south by wall 165, to the

west by wall 113 and to the east by wall 74.

Room 9

The room

measures 2.5x3.80 m and it is enclosed to the north by perimeter wall 29 (Fig.

16) together with adjacent room 4. The western limit is represented by wall

113 (1.40x3.70, H: 110 m), the east by wall 26 and the southern border by the

massive wall 78 (1x2.5, H: 0.80 m, mudbrick size: 37x24x9 cm), now entirely

removed from its original location. No associated floor levels have been found.

The removal of wall 78 revealed the presence of wall 165 and traces of a floor

associated to the same context (SU 138, -3.20 m), and preserved only where

bordering wall 113. It seems that this room had no obvious access.

In order to

reach the thick layer of fluvial pebbles and sand already detected last year in

trench 1, we proceeded with the removal of a layer of compact soil (SU 79)

found under floor SU 138 and under walls 26, 113, 156. As expected, this layer

covered a pebble layer (SU 82, -3.69 m) levelling the surface before the new

walls were built. On closer inspection, the pebble layer proved to be formed by

two similar strata. The first one (15 cm thick) contained only a few pebbles while

in the second stratum the pebbles were abundant. The provenance of the pebbles

is unknown but the large quantity suggests the presence of an ancient river

located nearby. The pebbles were laid beginning on the northern side, as demonstrated

by the inclination of the layer visible in the western section of trench 1

(2011 excavation). The deepening of room 9 allowed the exact identification of

the northern limit of the pebble layer, represented by wall 81 (Fig. 17).

The recovery of this wall is particularly important since it represents the

deepest and the most ancient architectural feature uncovered this year. In fact,

it is probably contemporary to the architectural structures unearthed in 2011

and dating to the 4th-5th century AD (see the

conclusions).

Room 8

This wide room

measures 4x3.70 m and it is enclosed to the north by the perimeter wall 29 (Fig.

18). To the east it is delimited by wall 113, to the south by wall 60

(4x0.8, H: 1.40 m) and to the west by wall 104 (2.90x0.95, H: 1.5 m). The

entrance is located on the west side and leads directly to the EW corridor. The

room was fully excavated, exposing two floor levels. The upper one (SU 120,

-2.80 m) is characterized by traces of fire, charcoals and by a rectangular

mudbrick structure (SU 125, 0.90x1, H: 0.25 m) located in the north-eastern

corner of the room. The lower floor (SU 135, -3.10 m), only partially

preserved, was found just in the central and eastern parts of the room. A small

probing trench opened in the south-western corner of the room revealed the

presence of a pebbles-and-sand layer similar to the one already detected in

room 9, confirming a matching stratigraphic sequence.

After the

abandonment of the room, which occurred probably in the 8th century,

another occupational phase dating to the 12th century was recognized.

The room, still delimited by the same walls, was converted apparently into an

open space. A U-shaped mudbrick bench (SU 110-112) was detected along the

western, northern and eastern walls whilst the central space of the room was

occupied by a trapezoidal mudbrick structure (SU 101) measuring 110x150x180 cm.

The stratigraphic sequence of this occupational phase is complicated by the

presence of several fire places, pit holes and two drains of significant

dimensions and dated to the 12th-13th centuries.

Room 7

The excavation

of this area (Fig. 19), initially interpreted as a room, was very

problematic because of a very disturbed stratigraphy. This space (3x3.80 m) is

delimited on the east by wall 104, on the north by wall 106 (1.20x5.15, H: 1.22

m) and on the west by wall 64 (1x8.50, H: 1.20 m). On the south, where we

expected to find the continuation of wall 60, we identified only a few aligned

mudbricks, not enough to confirm the existence of the wall. Moreover, the

presence of the EW corridor to the north from room 7 reinforced our hypothesis

according to which this area could be part of a wider hall located east of wall

64.

Under a layer close

to the surface (SU 80) and containing many ceramic fragments, two deep pit holes

of irregular form (SU 100, 108) were excavated. The pit holes filled almost the

whole room and destroyed the surrounding walls in several points. A remarkable amount

of ceramic fragments and jewellery, mixed with soft soil and pebbles (debris?)

were found inside the pit holes. A precise identification of the shapes of the

holes has been proven difficult by the softness of the soil contained in both

the fillings and it is not excluded a contamination of the materials. Under the

holes there was a compact layer of soil (SU 117) containing several small finds

and a copper coin. The deepening of this layer revealed the foundations of

walls 64, 104 and 106. These walls were built on foundations (SU 123-124-217) made

of compact clay and built directly on a pebbles-and-sand layer (SU 122), similar

to the pebble layers already recognized under rooms 8 and 9. The foundations are

not present in clay walls of this kind and the walls are usually built directly

on top of the natural soil. We can therefore assume that the construction of

foundations depended on the presence of pebbles layers in the walls and was aimed

to offer a more stable support to the later walls. No floor level has been

identified in this room.

A similar

stratigraphy was detected in the EW corridor situated to the north of this

area. A deep pit hole (SU 99) containing ceramic fragments and small objects

was identified in the corridor. The underlying layer of compact soil (SU 118)

contained several small finds as well, including a chalcedony seal.

Western sector

Room 6

The room

measures 2.70x2.6 m and it is enclosed by walls 66 (7.9x1.20, H: 1.3 m), 67

(5.2x1.2, H: 1.5 m), 69 (13.3x1, H: 1.4 m) and 68 (3.5x1.30, H:1.77 m) (Fig.

20). The entrance is located on the northern side and opens into the EW

corridor. Wall 211 was built at a later date against the western wall. The room

contains a mudbrick bench (0.57 m wide, H: 0.25) only partially preserved.

Rooms 10-11-12

Room 12 measures

3.80x4 m and is enclosed by walls 68, 69, 181 (3.8x0.9, H: 1.30 m) and 182

(4.5x1.10, H: 1 m) (Fig. 21). The clearance of the related earthen floor

SU 194 (-3.25 m) revealed a substantial quantity of big pebbles (10 cm long)

laid in the north-eastern corner of the room. Contrary to the layers uncovered

in the eastern sector, here the pebbles are not mixed with sand and they

abut an earthen structure (197) found under the floor SU 194 as well. Further

researches could reveal the exact nature of these features.

In a subsequent

building phase the room was filled with a layer of compact soil (SU 193), on top

of which it was built partition wall 183 (0.40x3.90, H: 0.5 m). This wall was

made by rows of headers (mudbrick measure: 40x23x9 cm), some of them not well

distinct because of the erosion of the lateral surfaces. Three round holes (Ø:

6 cm) characterize the upper part of the wall and were used probably for

ventilation or for hanging foodstuff. Wall 183 divided the previous room 12

into two smaller rooms, labelled respectively 10 (1.80x3.90 m) and 11

(3.80x1.80 m) and featuring flattened floors SU 178 and SU 189. The second

floor, showing traces of fire, was laid on a layer of compact soil (SU 195)

containing fragments of moulded khum with dark slip (6th-7th century AD). The entrance to these rooms were not found but we hypothesize the

presence of a passage in the eastern part of wall 69, where it is visible a

sort of pit hole, still not investigated.

In the following

building phase, other two walls (188-190) were built in room 11, narrowing the

surface furthermore (3x1.60 m). The mudbrick wall 188 (5x1.1, m) was built on

the previous partition wall, 183, and on wall 182, while wall 190 (1.10x0.40,

H: 0.09 m), made with only one row of headers, was built between walls 188 and

68. During this phase wall 68 was plastered again (plaster is 10 cm thick). It

is noteworthy the presence of an iron arrowhead dating to the beginning of the

8th century, discovered under wall 188. The last occupational phase

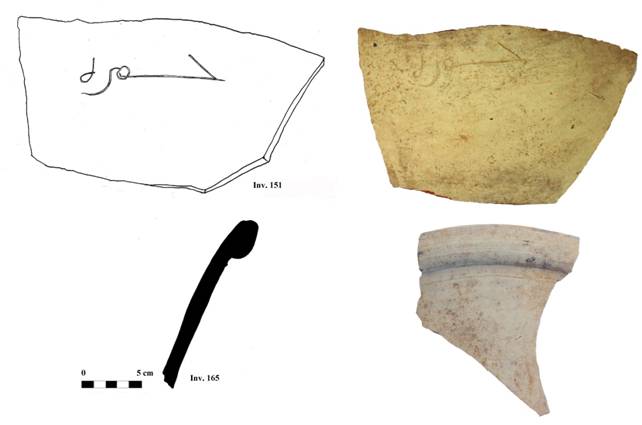

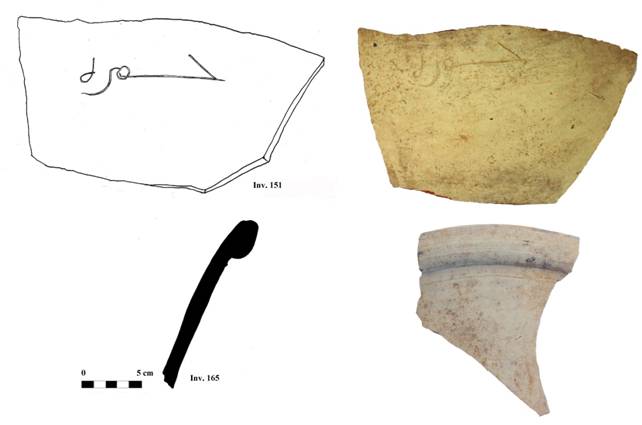

is represented by a round cesspit (SU 180, Ø:1 m, H: 1.2) cutting the wall 183.

The filling is made of a compact layer of greenish soil, which contained

several fragments of a wheel-made khum dating to the 12th century

AD. One fragment carries an incised inscription in Arabic (recognized the

letter –ah).

Courtyard

The

investigation of the area to the south from rooms 4-12 revealed a wide-open

space or a courtyard, probably leading to the entrance of the palace. This area

was delimited on the west by wall 218 (3x1.2, H: 0.36 m), on the north by the

walls 216 (1.37x0.60 m, H: 0.7 m) and 182, while on the east it was enclosed

by wall 66. The 17th century furnace uncovered in 2010 and abutted to

wall 182 has not been removed yet. The southern side reaches the limits of the excavation.

A related compacted floor (SU 185, -3.00) was identified on the surface

delimited by the walls. The presence of wavy gaps (2-3 cm wide) on the western

part of the floor remains unclear (channels made by the streaming of pluvial

water?) (Fig. 22).

Upper levels

As already

mentioned, the upper levels investigated during the 2012 campaign refer to an

occupational phase dating to the 12th-13th centuries AD.

The main evidences consist of ashy areas, pit holes, cesspits (badrab)

and drains (tashnau) made by one or more inverted jars buried into the

ground (Figg. 23, Pls. 14, 17). These features were often grouped close

to each other, demonstrating the preference for specific areas. The absence of

relevant architectural remains suggests that the pre-existent structures were

re-used with limited new building activity.

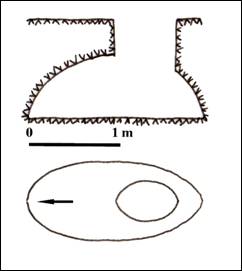

Several burials

were also found in different areas of the excavated trenches. Two of them,

clearly identified as Muslim graves thanks to the northward orientation, were

built excavating an oval subterranean chamber into the ground (Fig. 24).

Another type of burial, found on the same year, consists of oval holes 30-40 cm

deep, very simple, unadorned and probably produced very quickly. The graves

intersect the levels dating to the 12th-13th centuries,

suggesting that the citadel became a graveyard at a late period. Currently

there are not enough elements to propose a more precise dating considering also

the absence of grave goods.

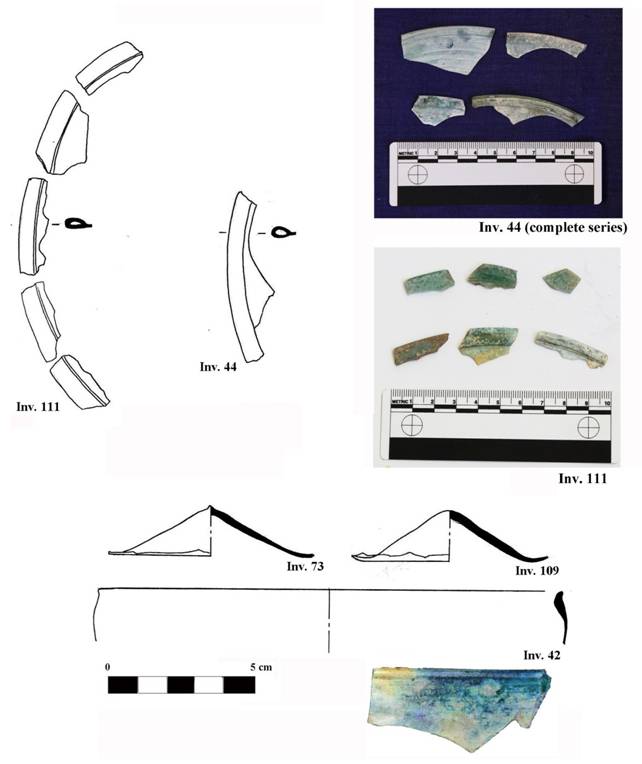

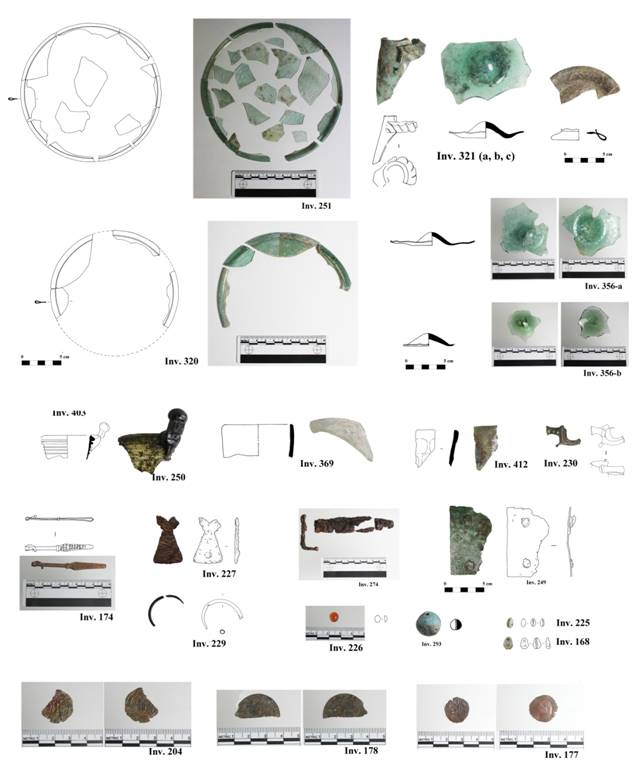

Finds

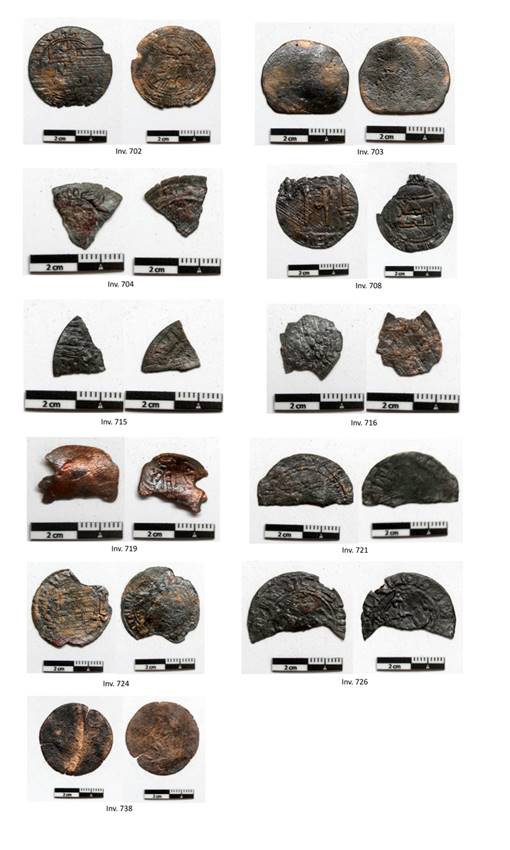

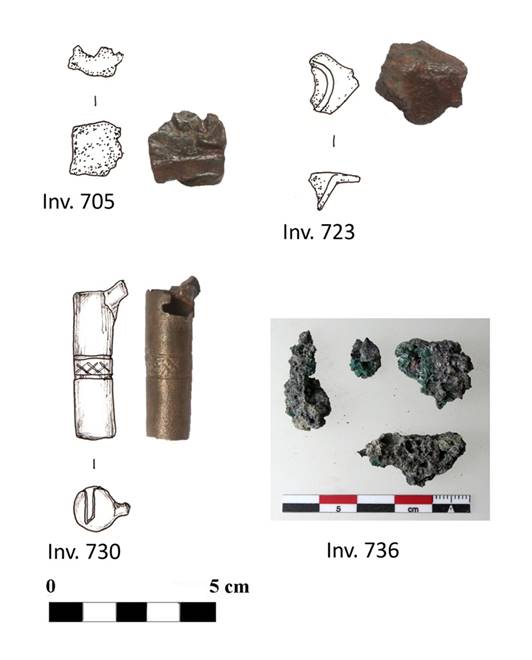

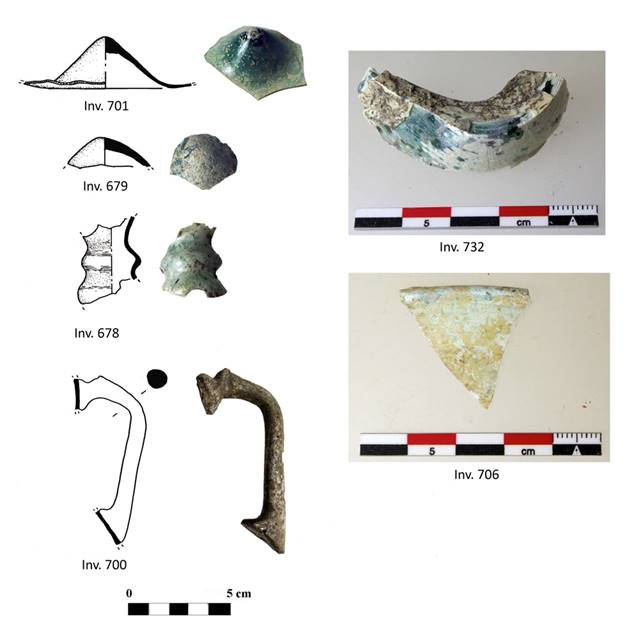

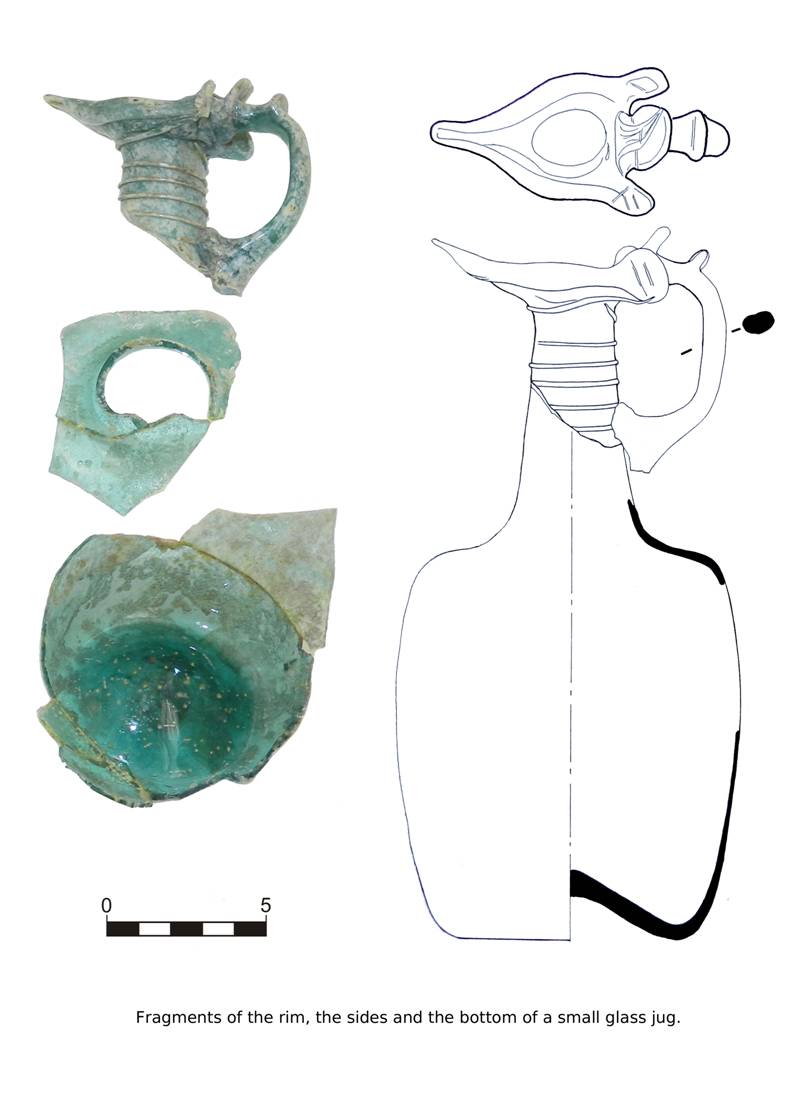

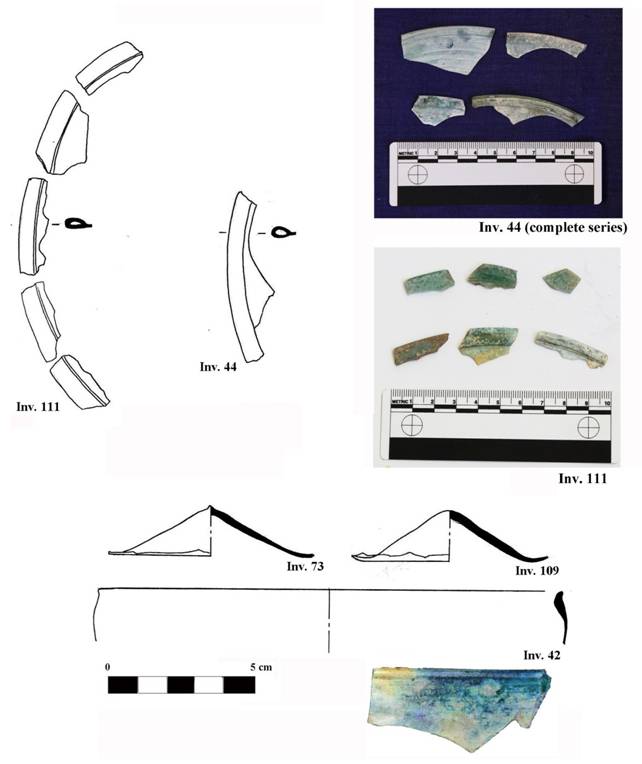

During the 2012

campaign we selected a total of 167 finds to be catalogued, among them

potsherds and small finds in bronze, iron, glass, bone and stone. Each find was

recorded in an inventory and both photographed and drawn. The ceramic finds,

mostly fragmented, can be divided into two chronological groups: the Early

Medieval pottery (6th-8th centuries AD) and the Medieval

pottery (12th-beg. 13th centuries AD). Since the citadel

was not inhabited between the 9th and the 11th centuries,

accordingly no ceramic vessels belonging to this intermediate period were

found, except for a few fragments of glazed lamps dating to the 9th-

10th centuries AD. Some later vessels dated to the 18th-19th centuries were recorded as well.

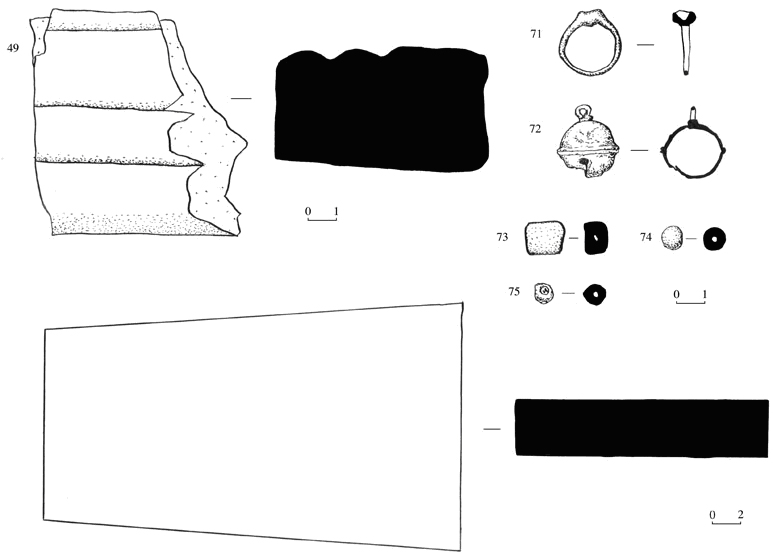

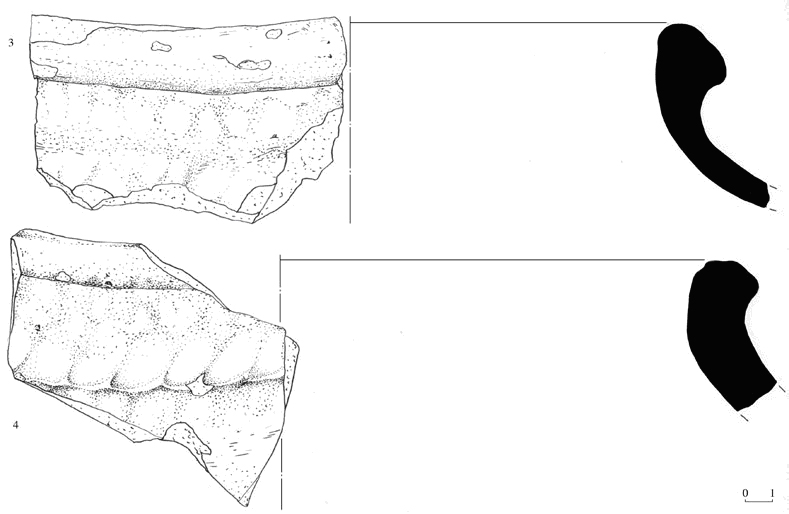

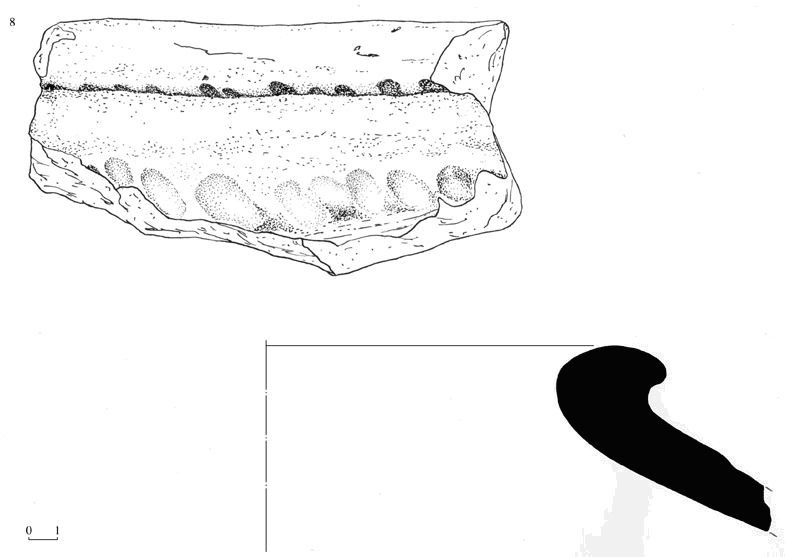

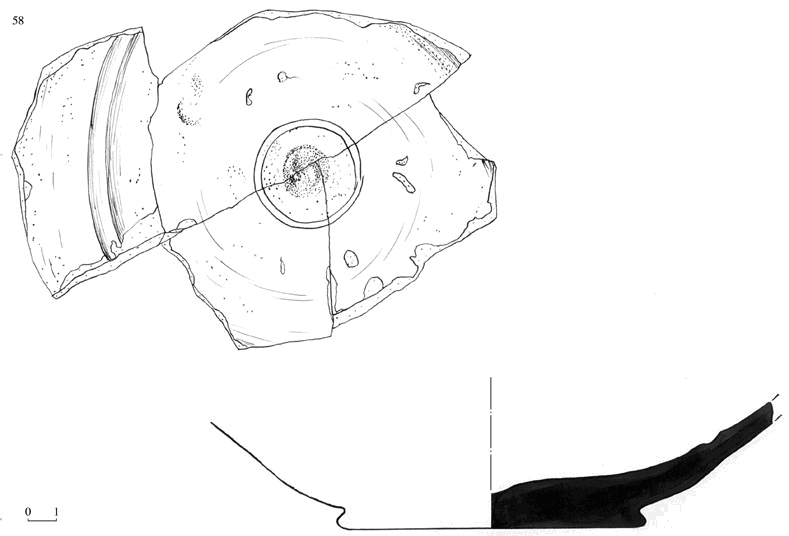

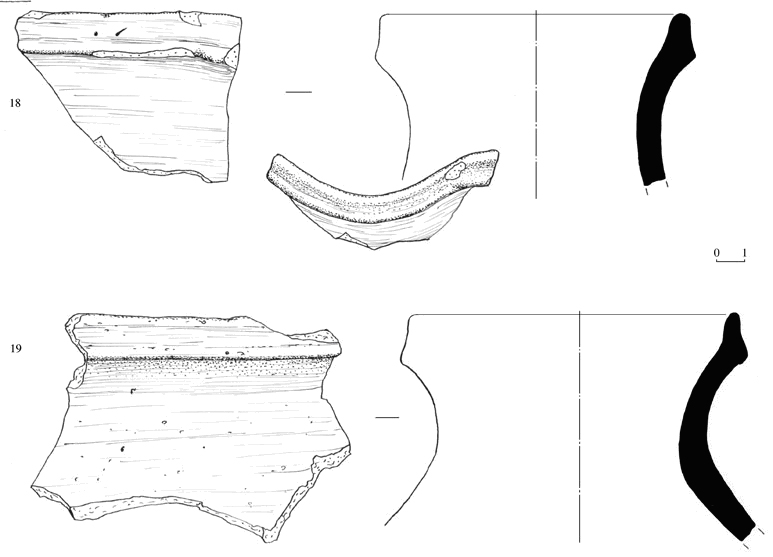

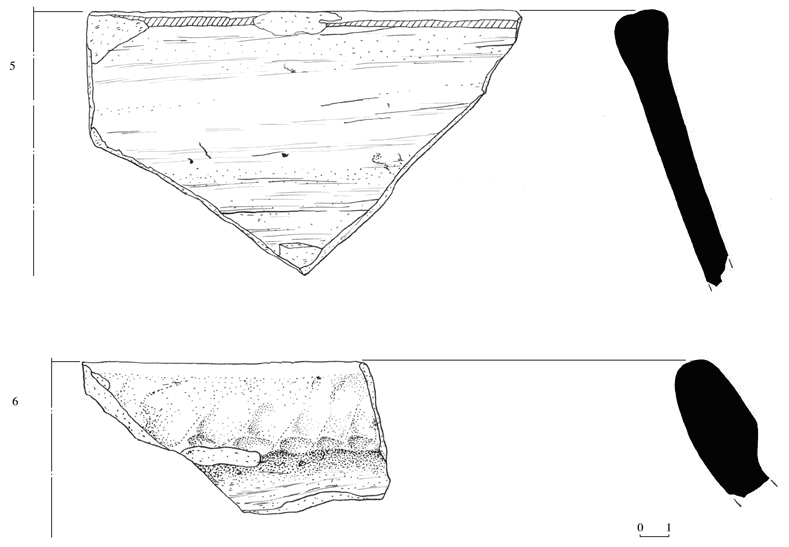

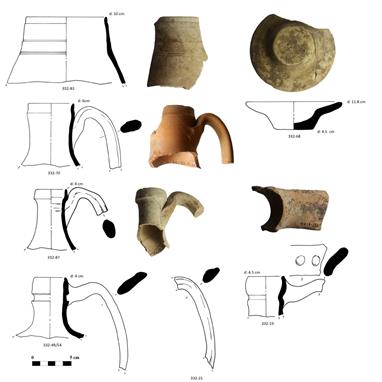

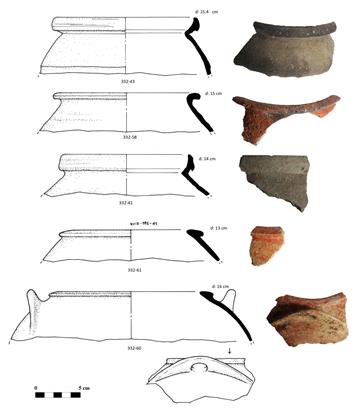

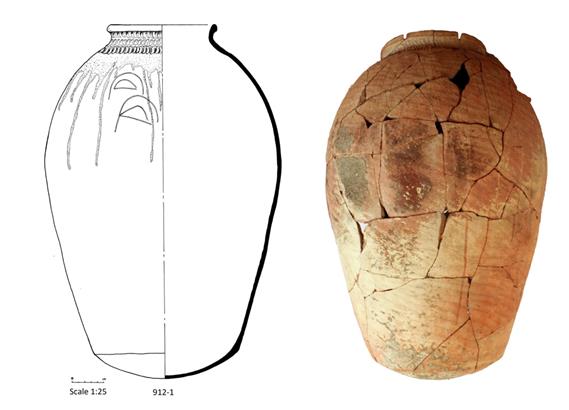

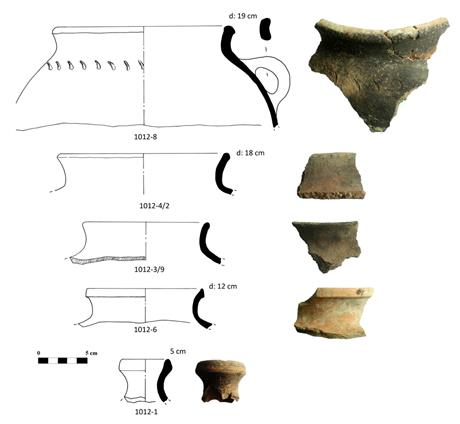

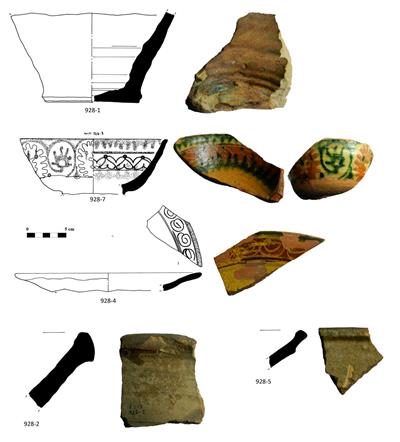

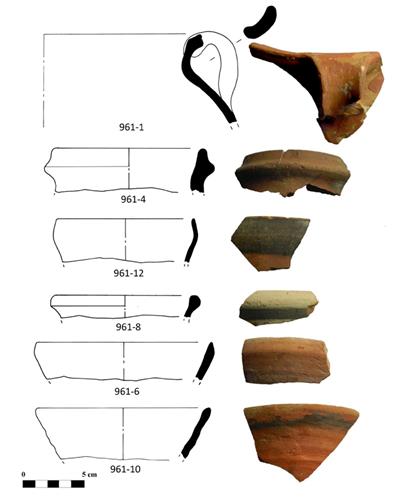

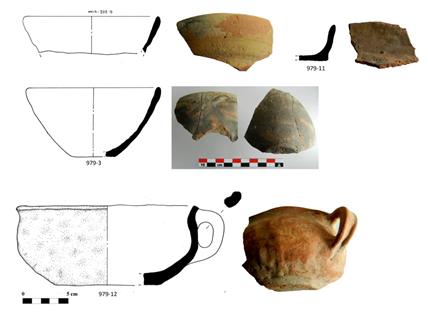

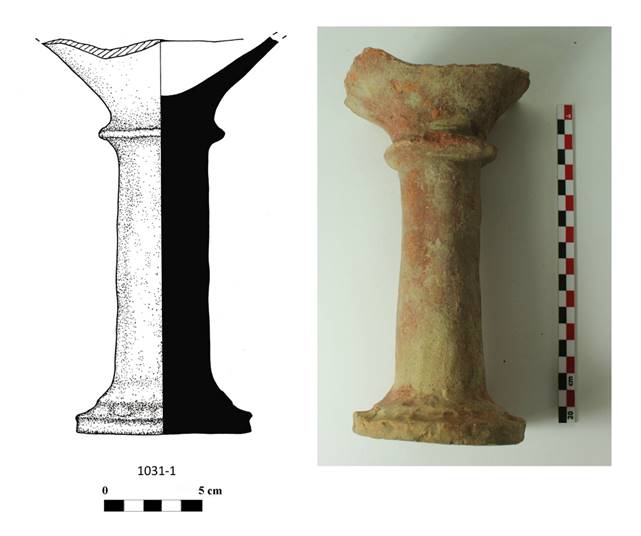

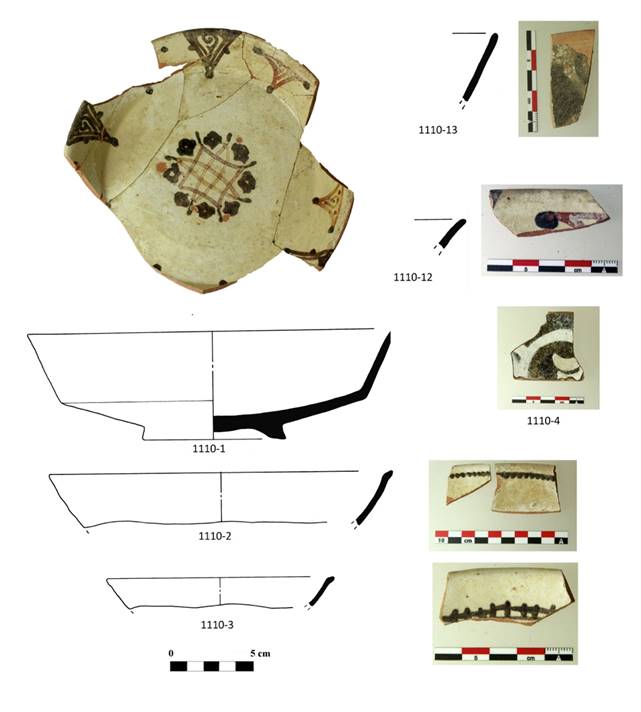

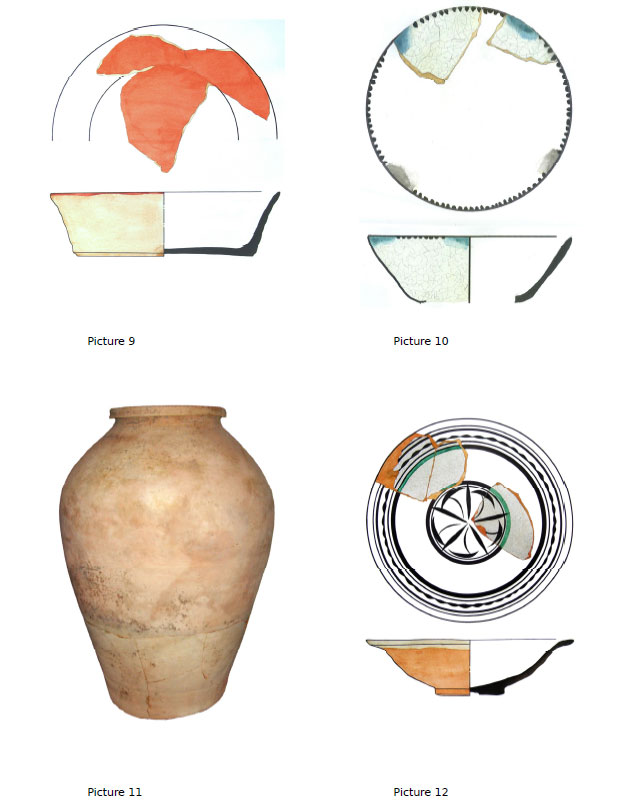

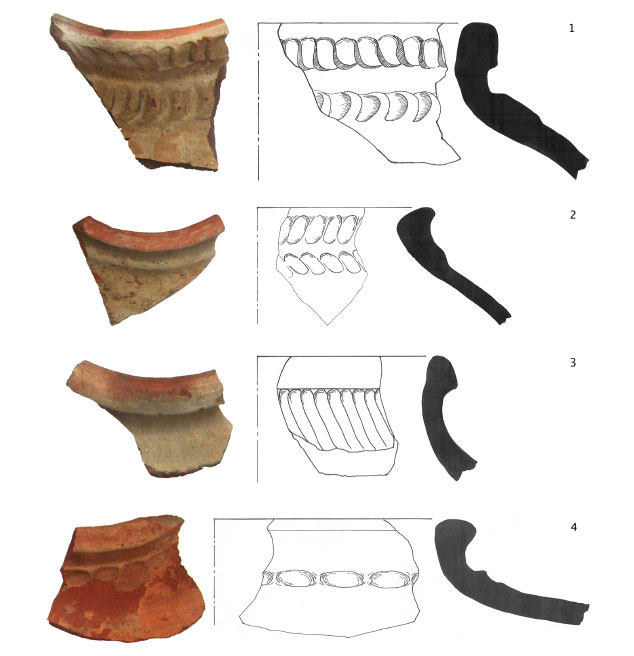

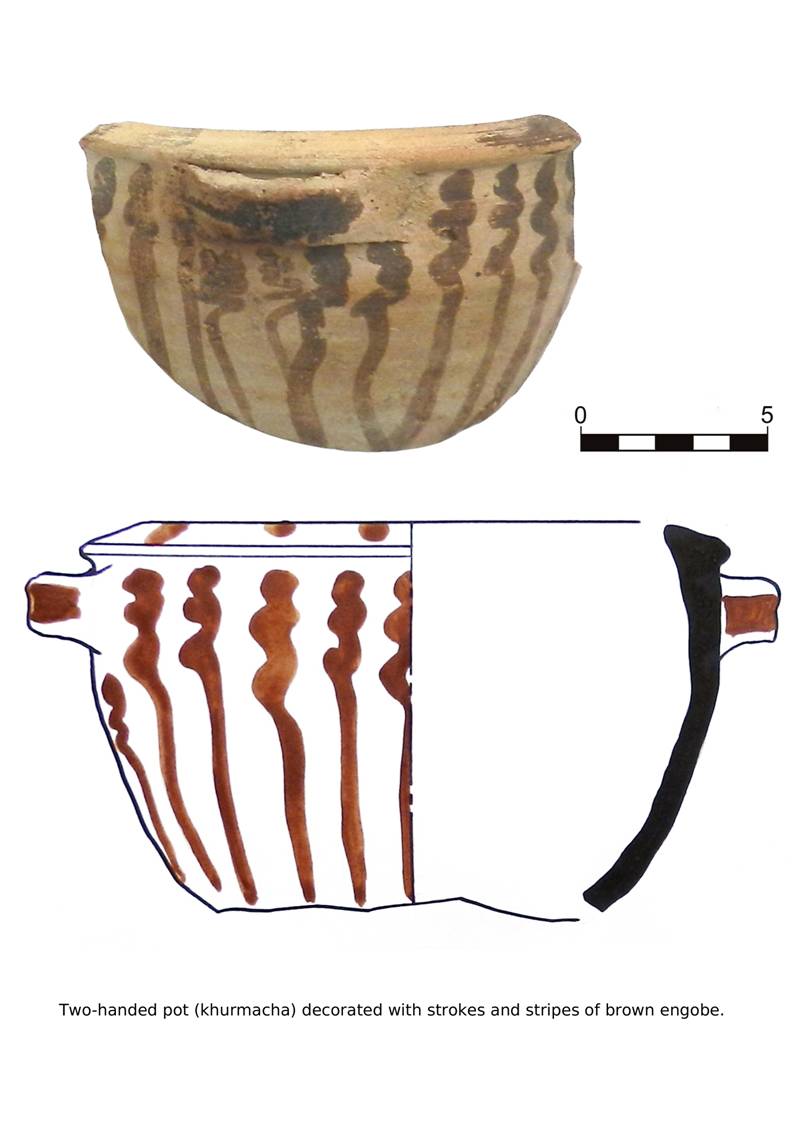

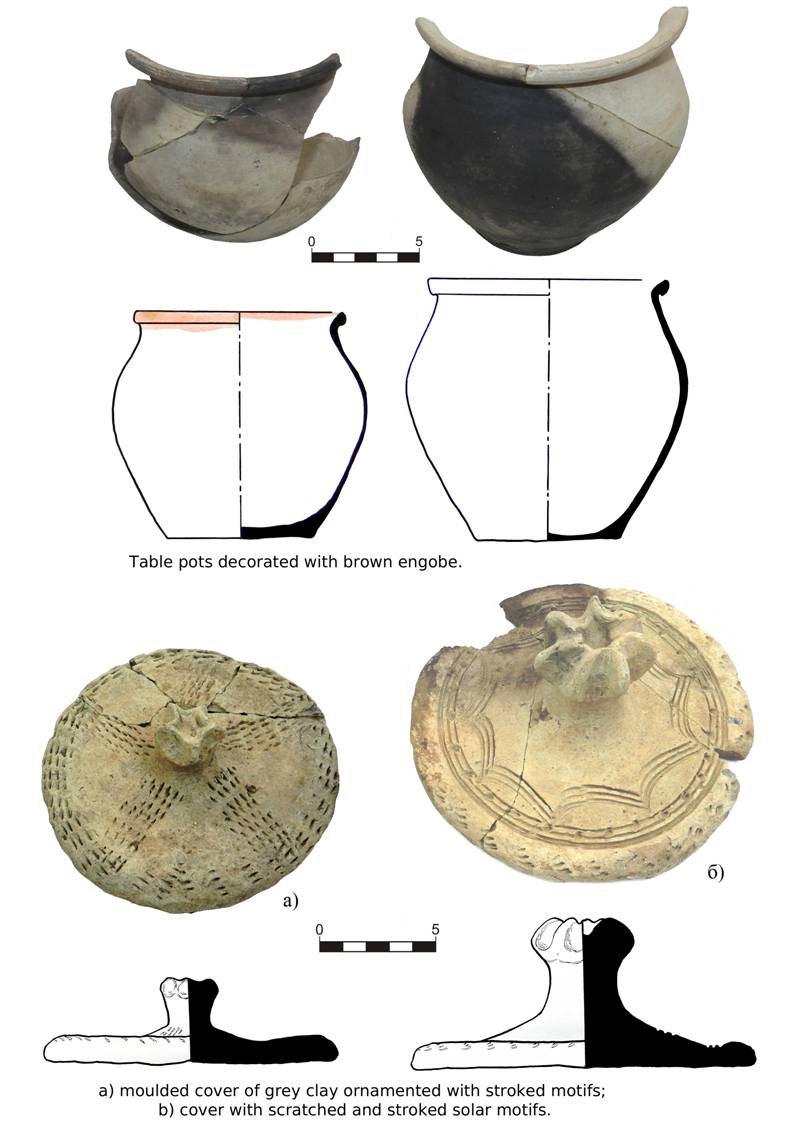

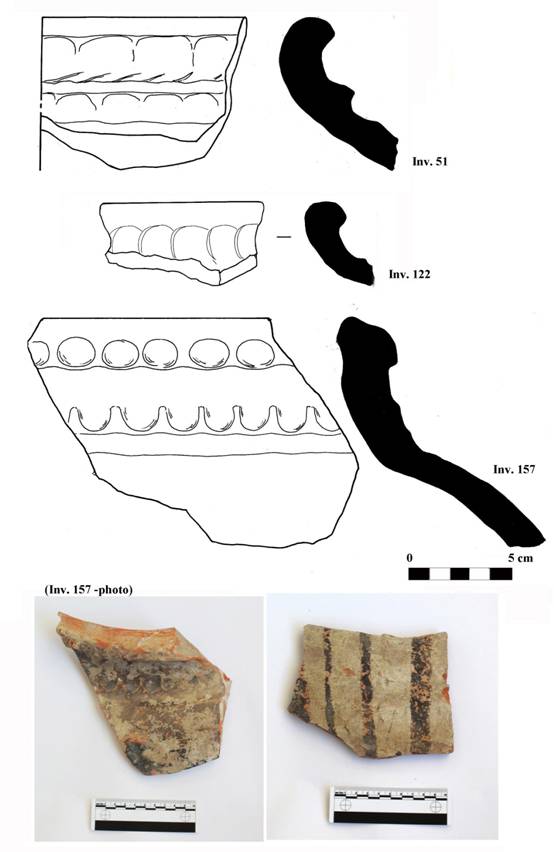

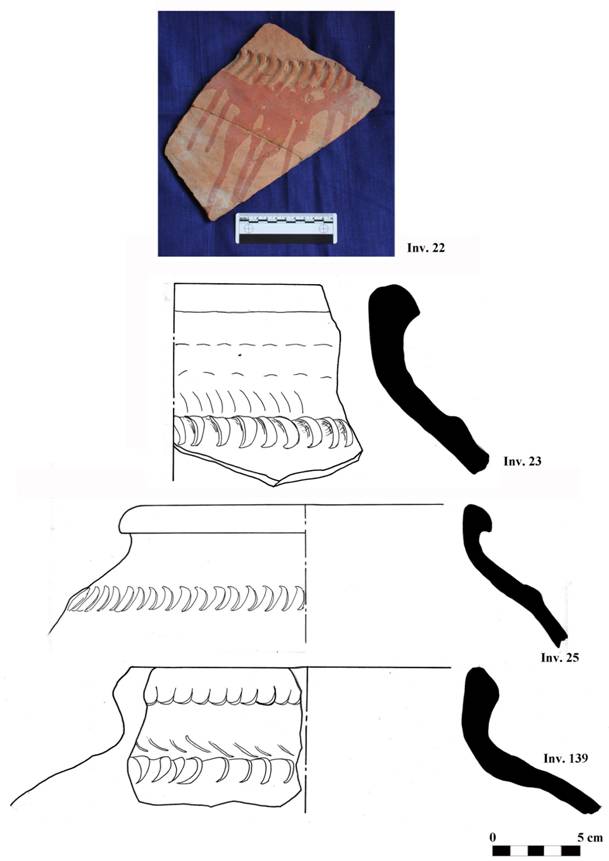

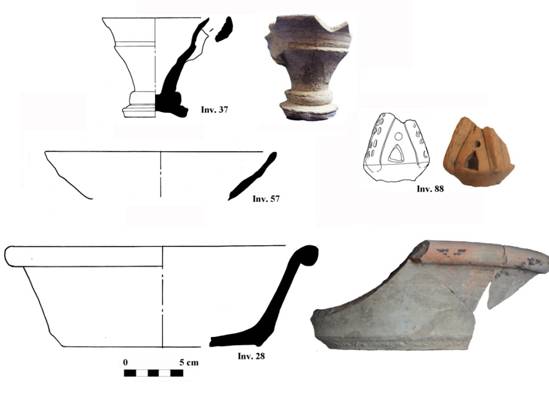

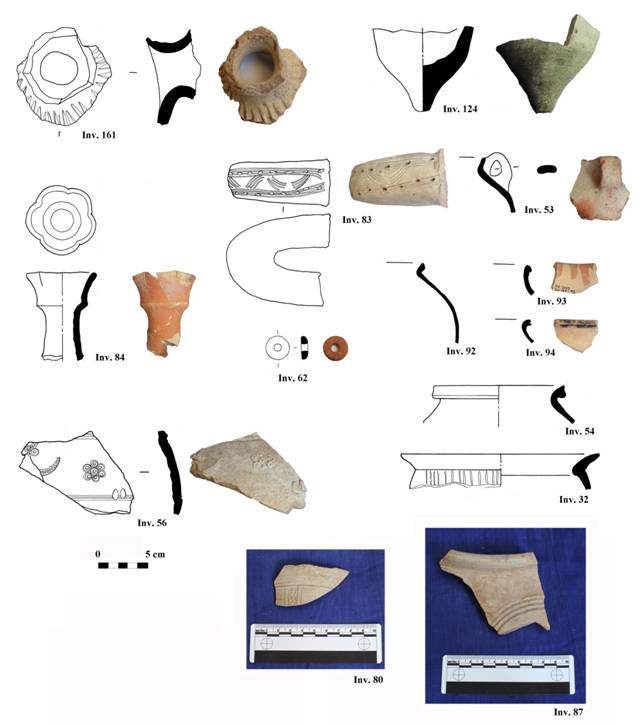

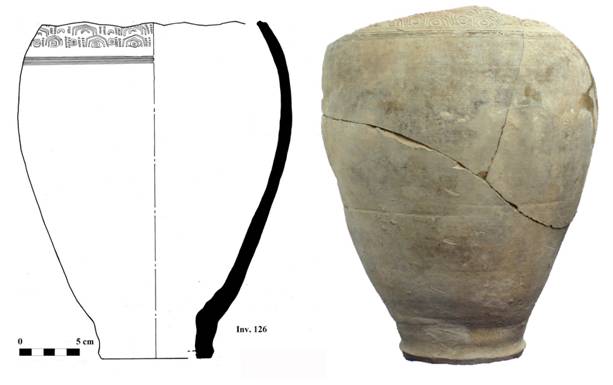

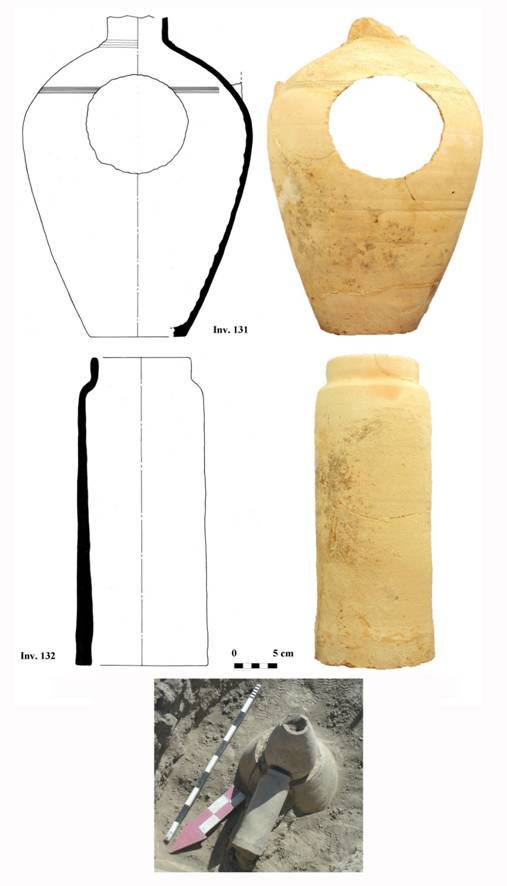

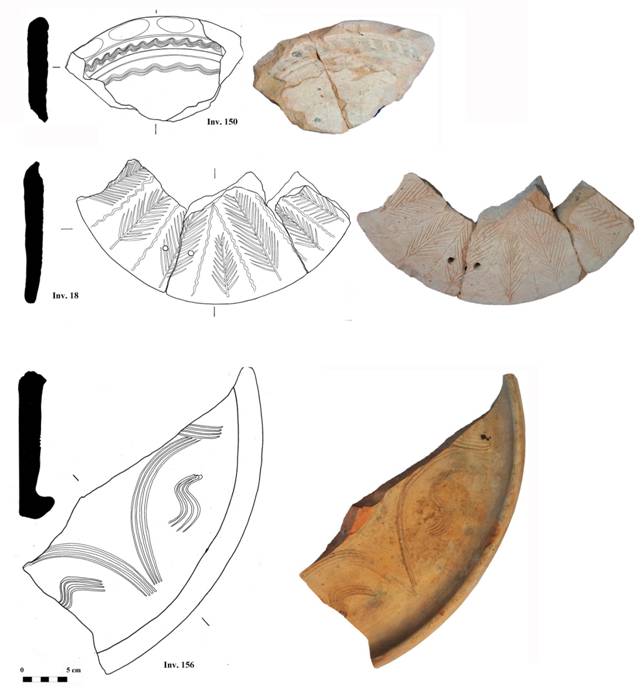

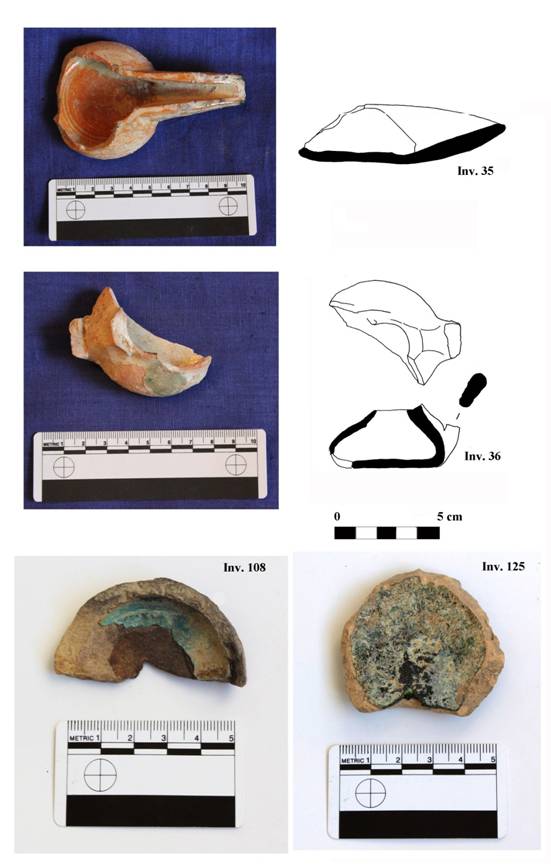

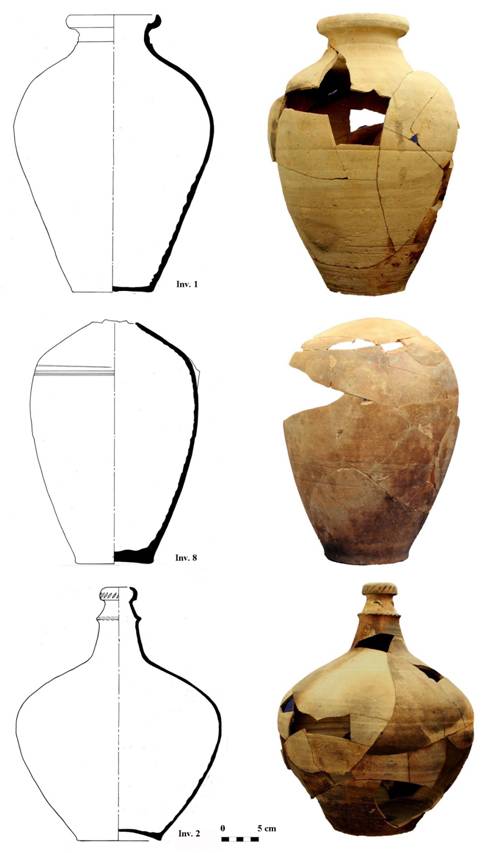

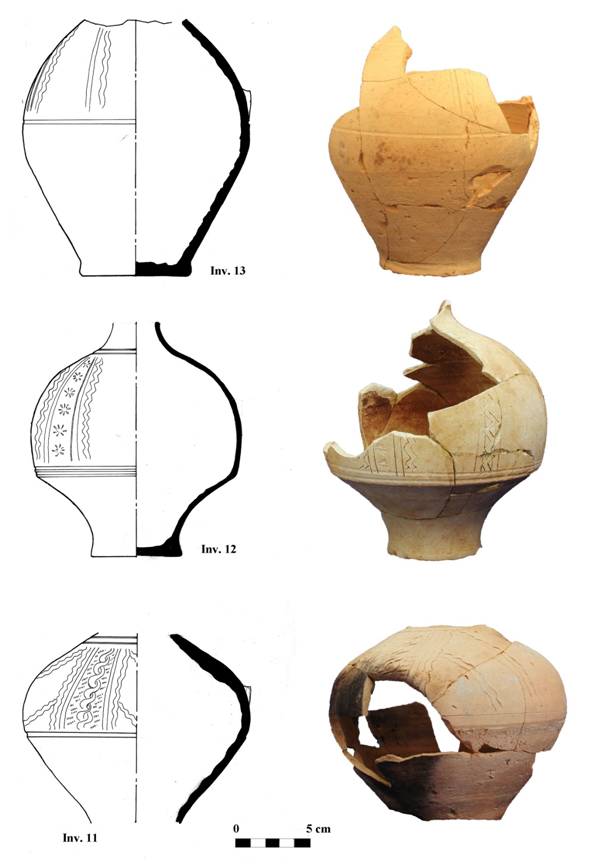

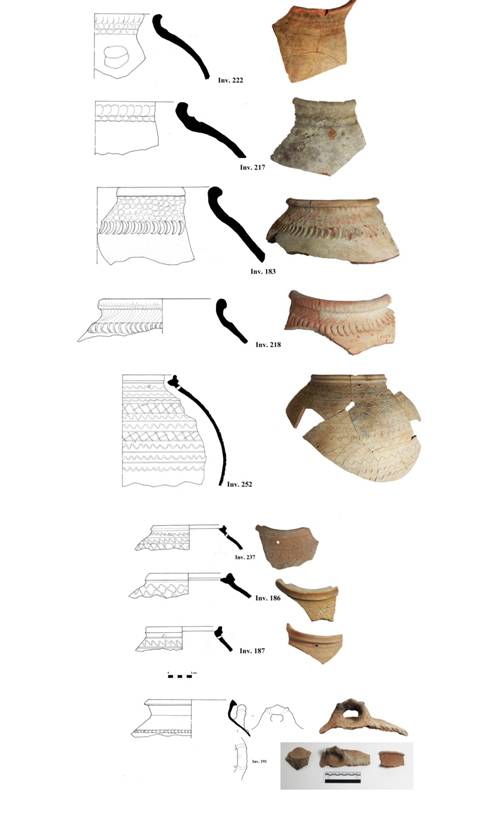

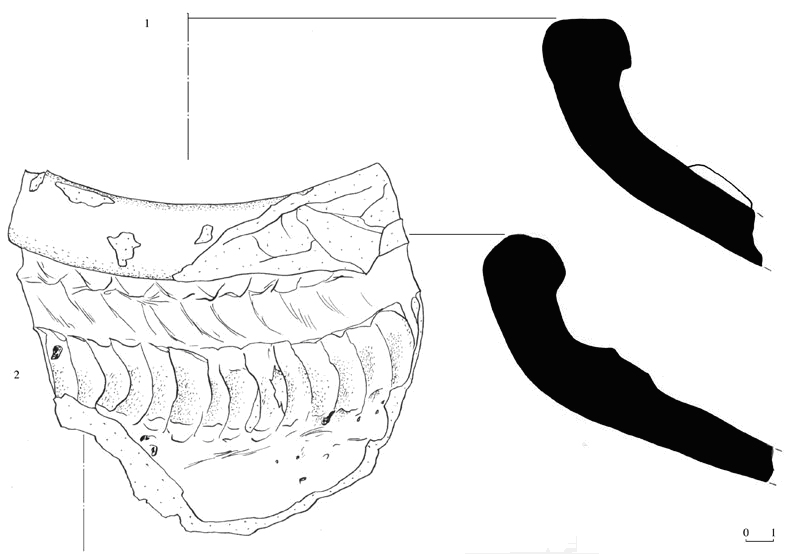

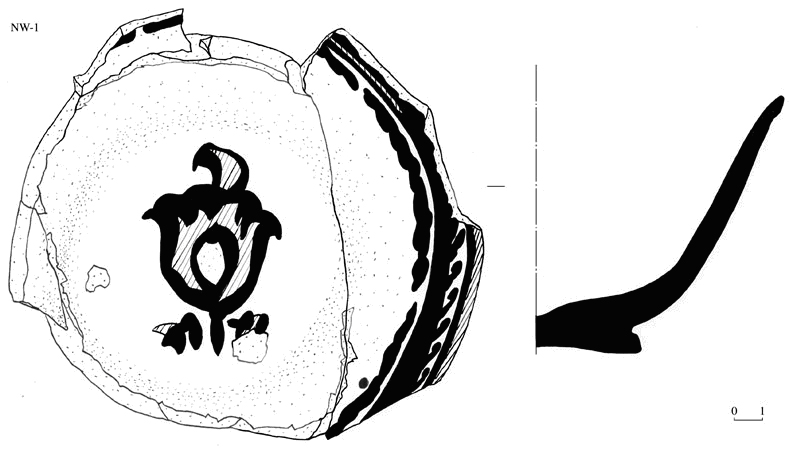

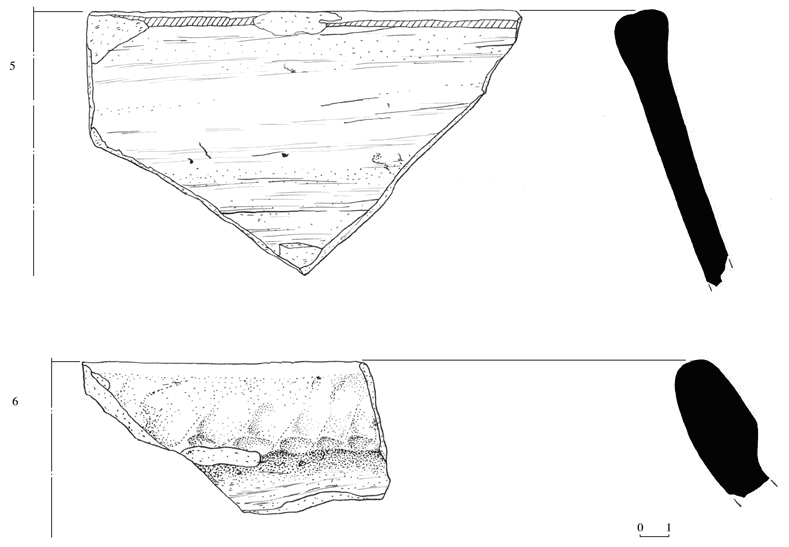

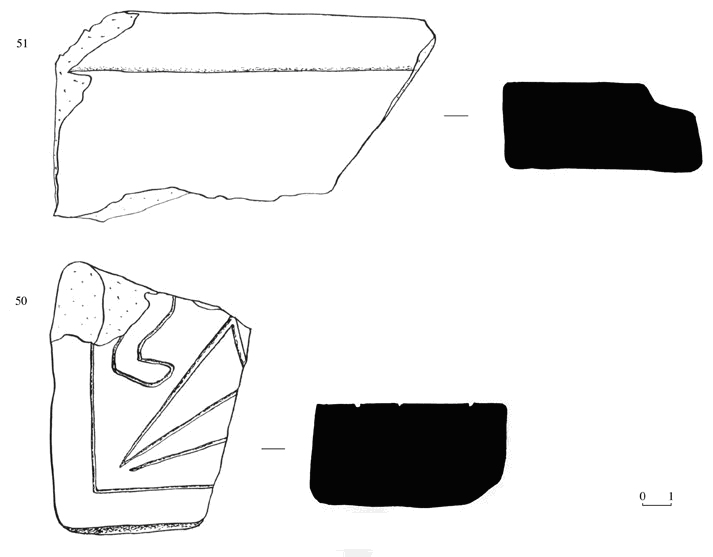

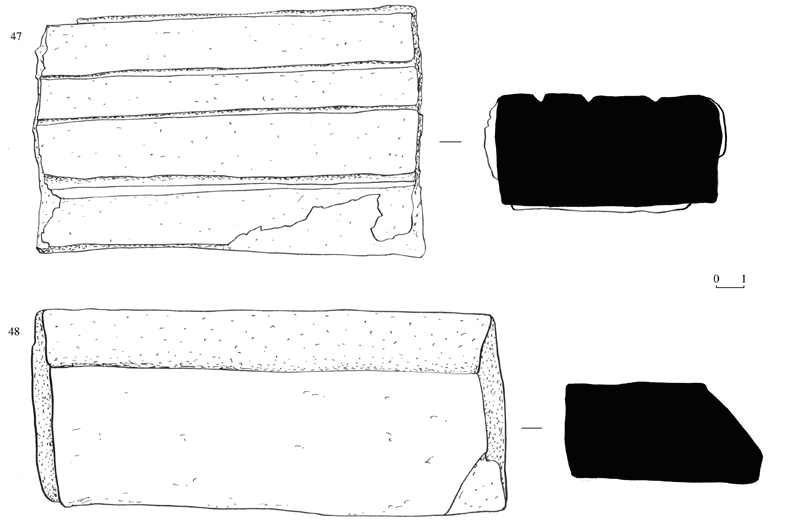

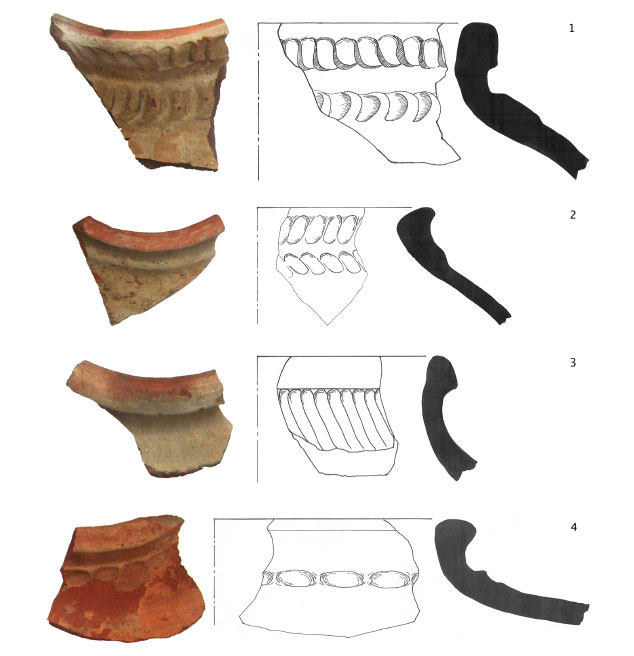

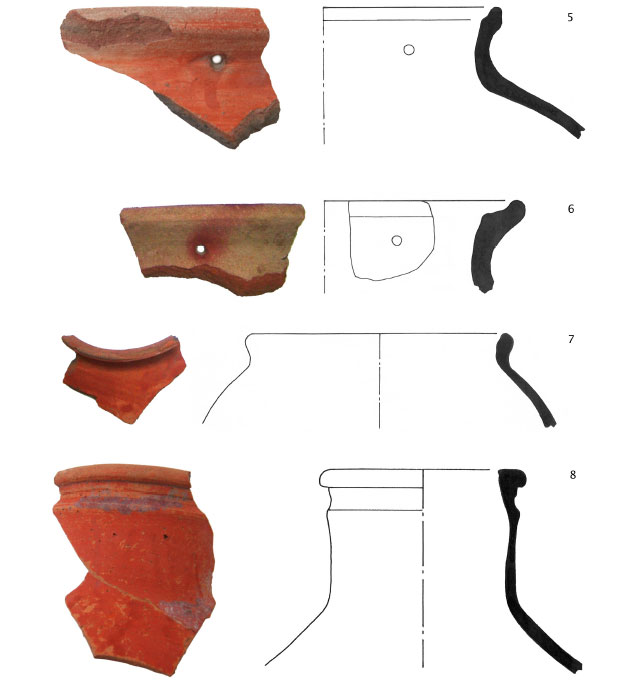

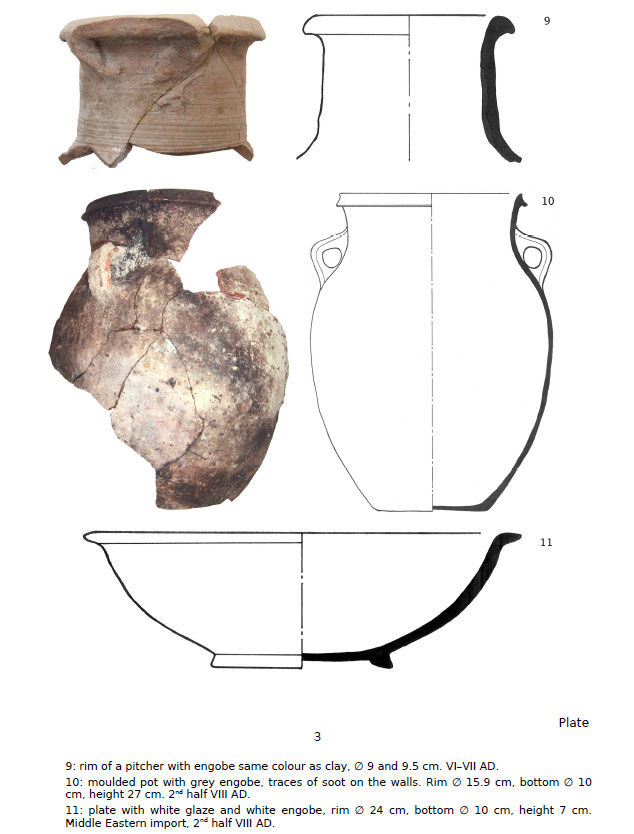

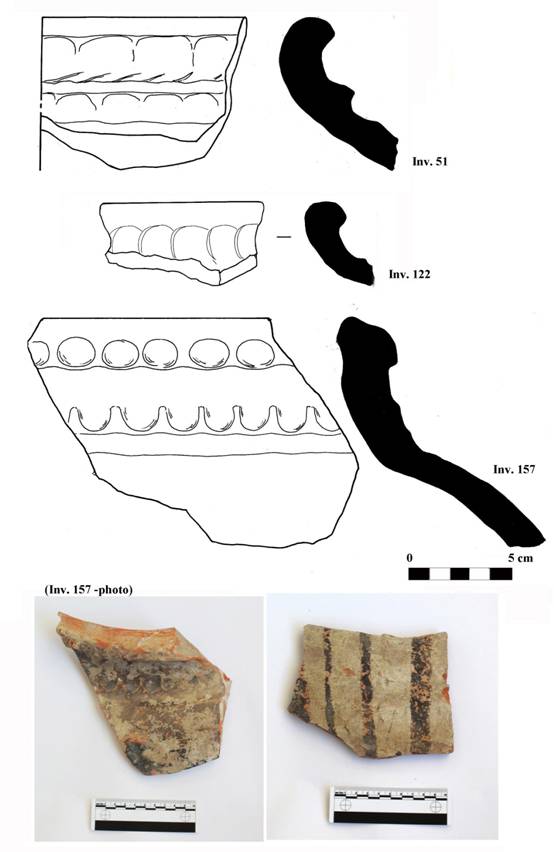

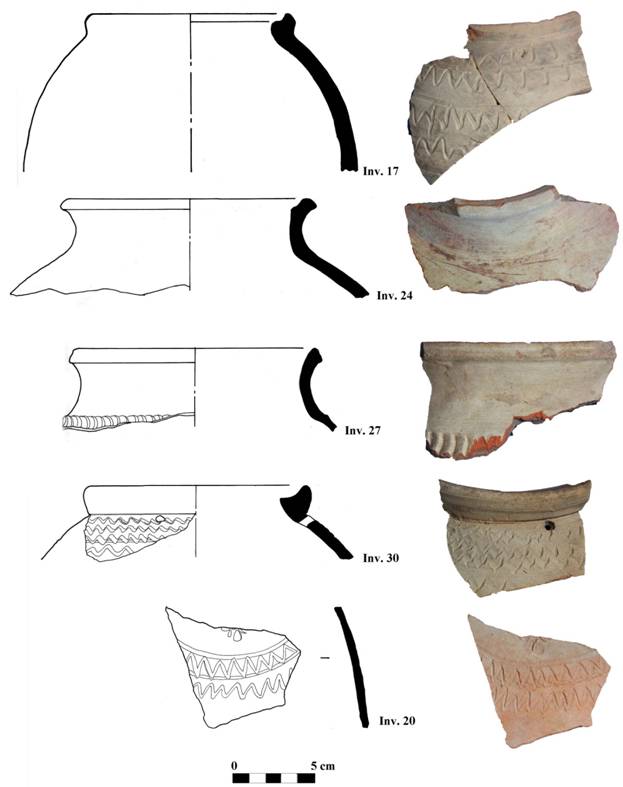

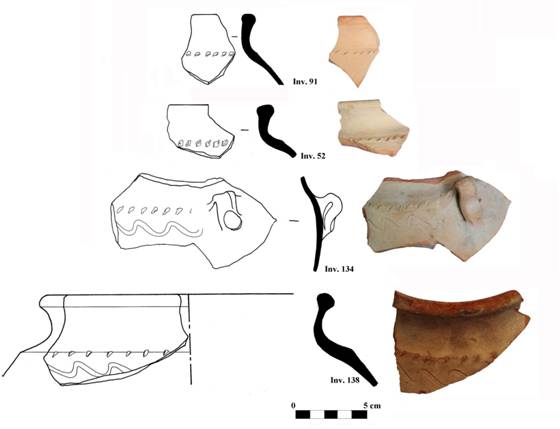

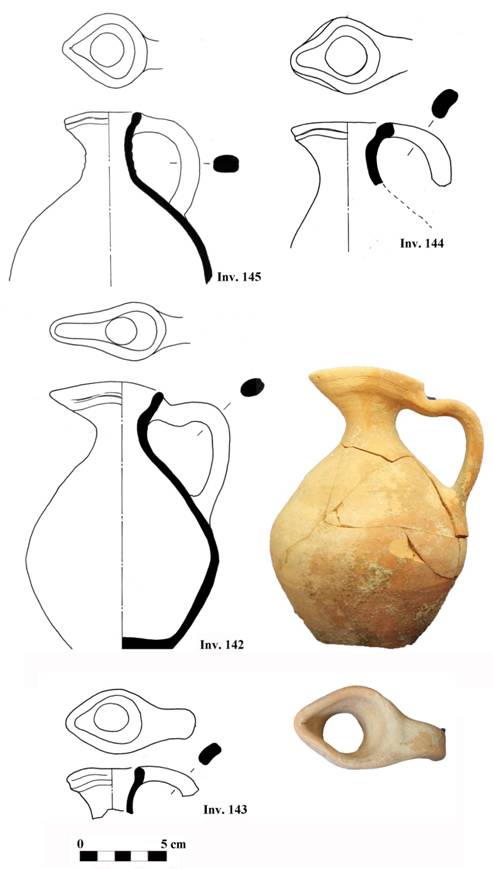

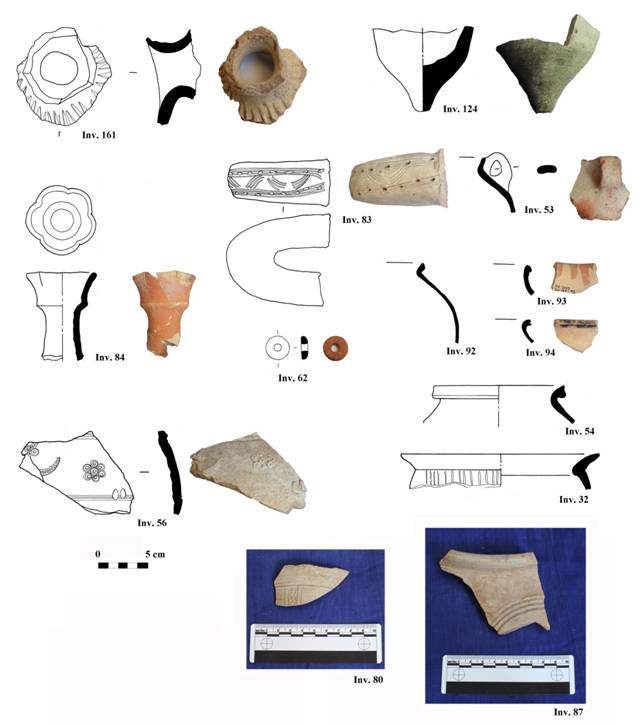

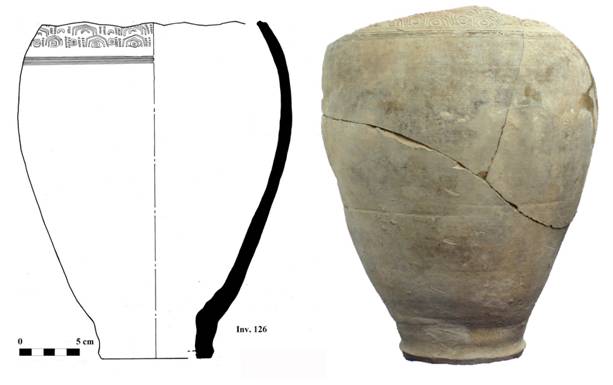

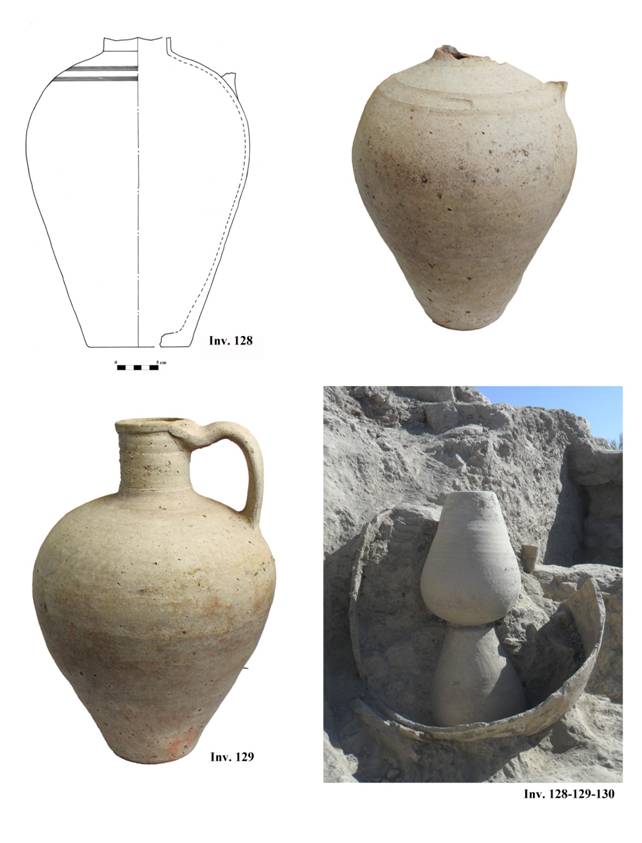

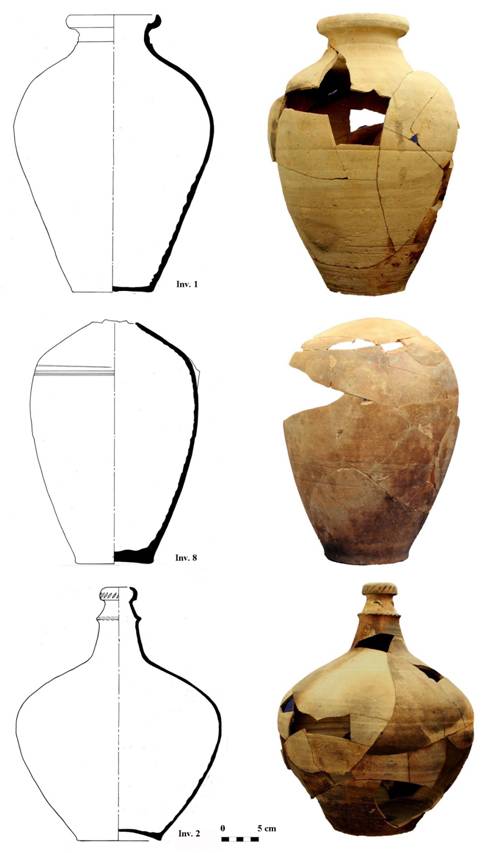

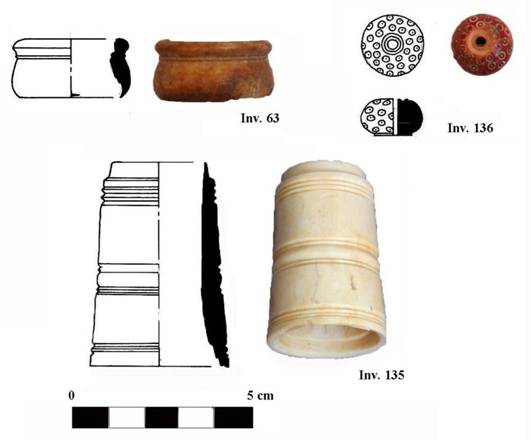

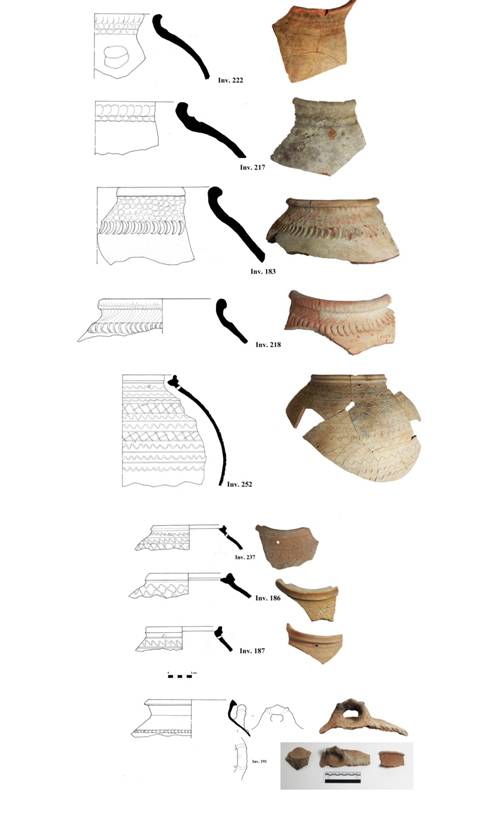

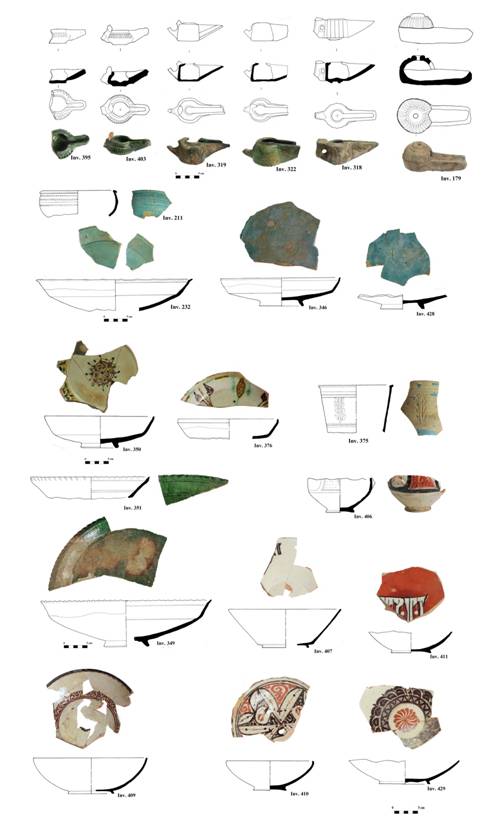

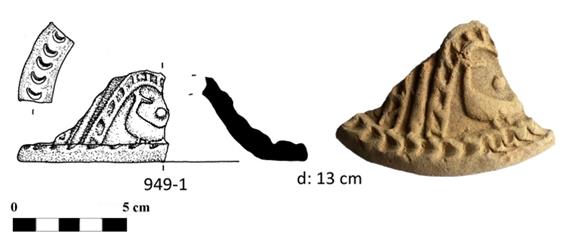

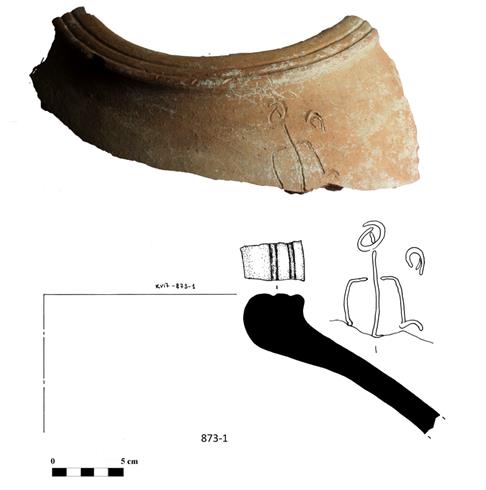

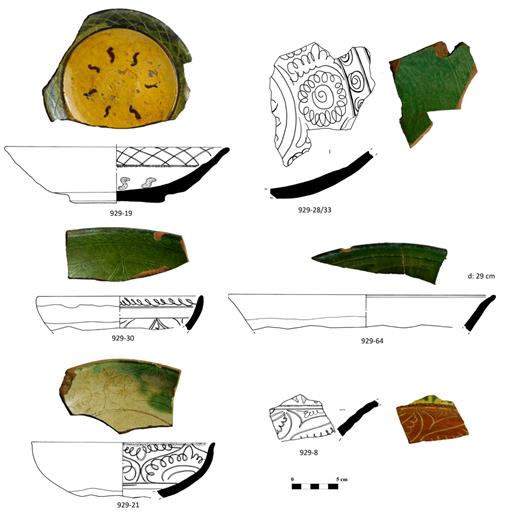

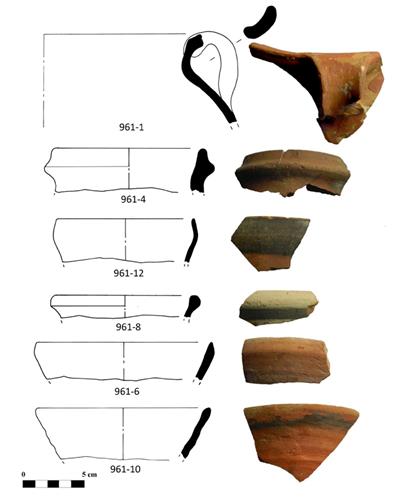

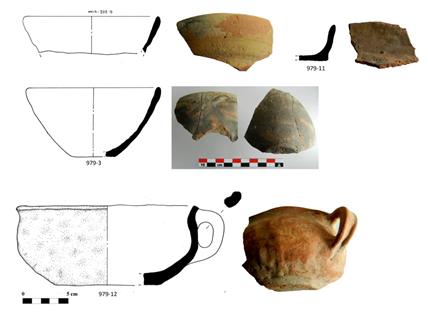

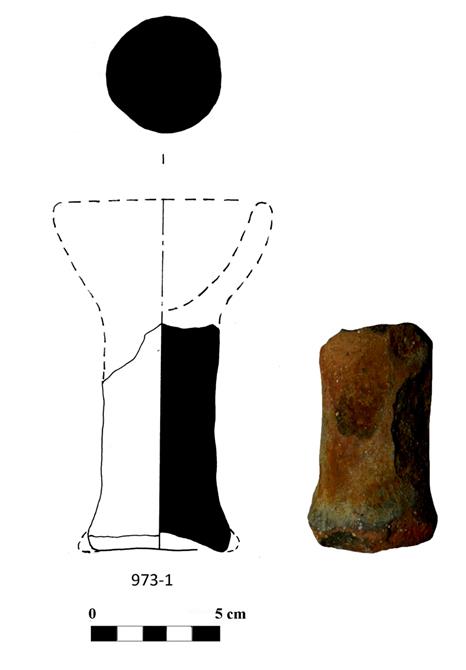

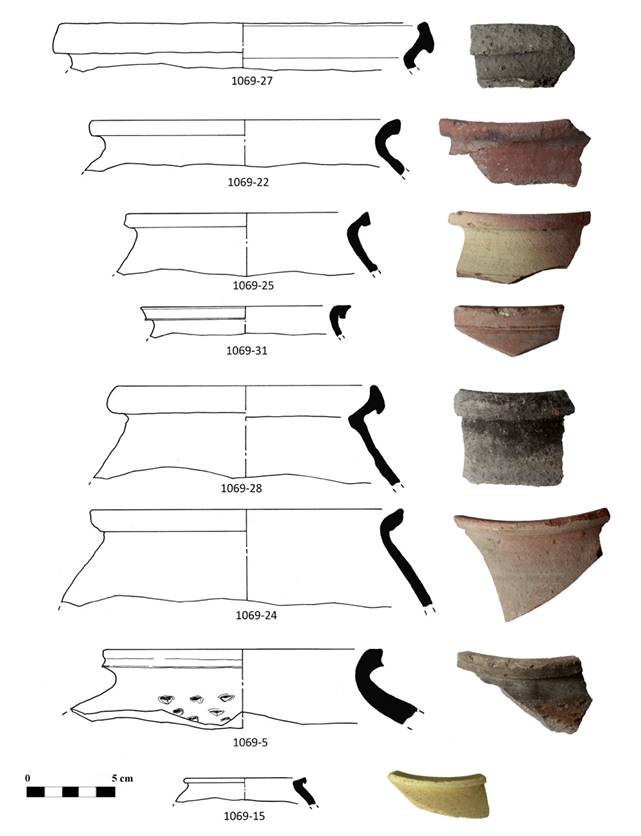

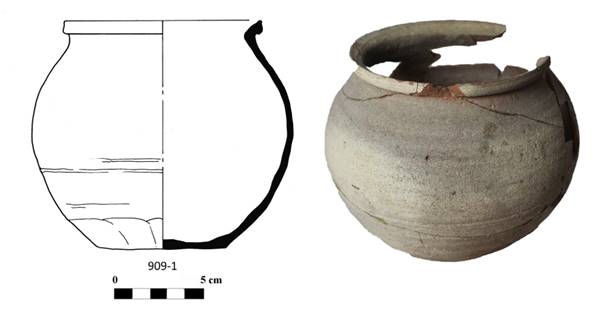

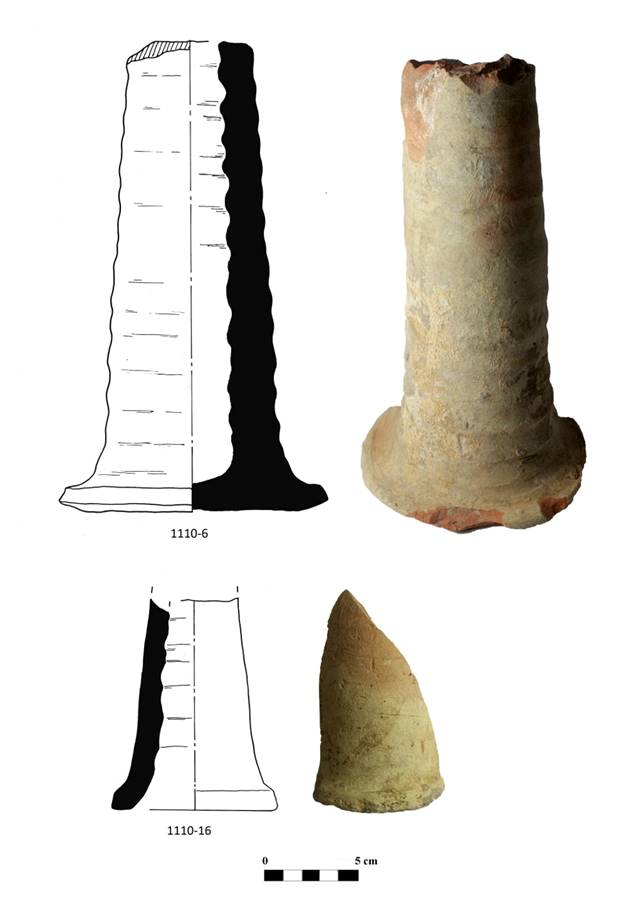

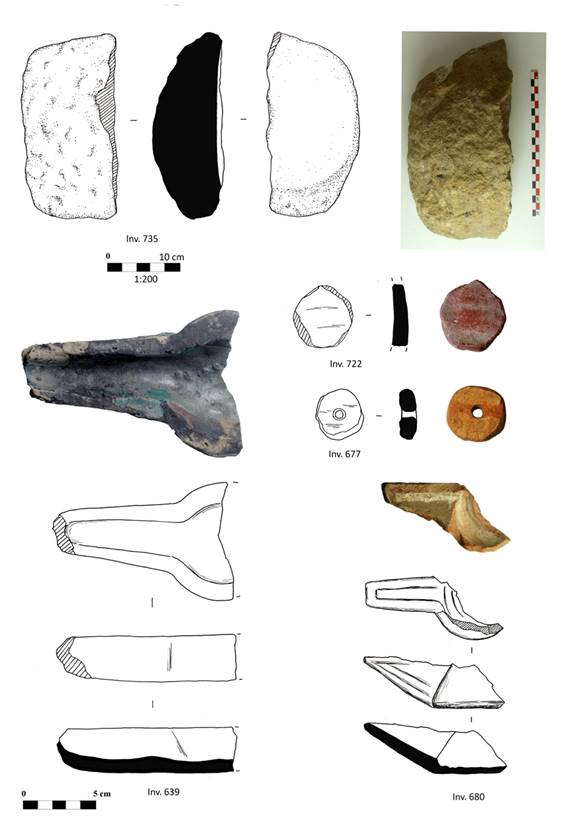

Among the Early

Medieval pottery, mostly found in the layers formed following the abandonment

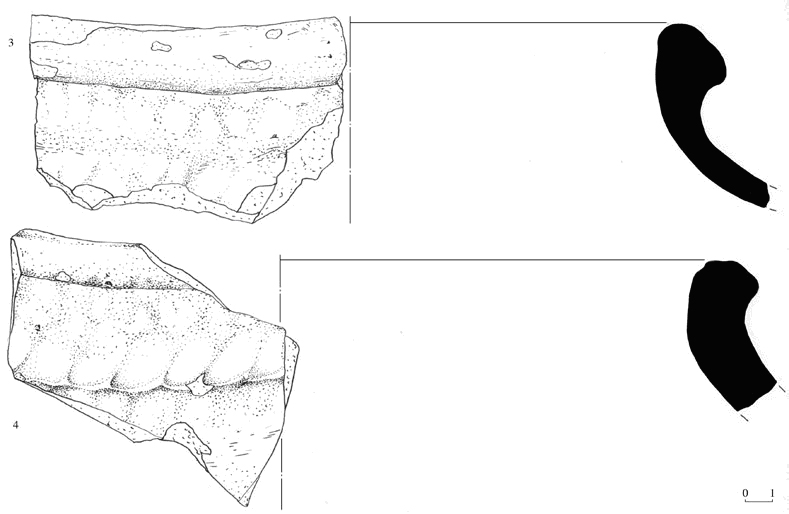

of the citadel, two distinct groups were identified. The most ancient group is

dated to the beginning of the 6th- first half of the 7th centuries AD, while the second group dates to the second half of the 7th-

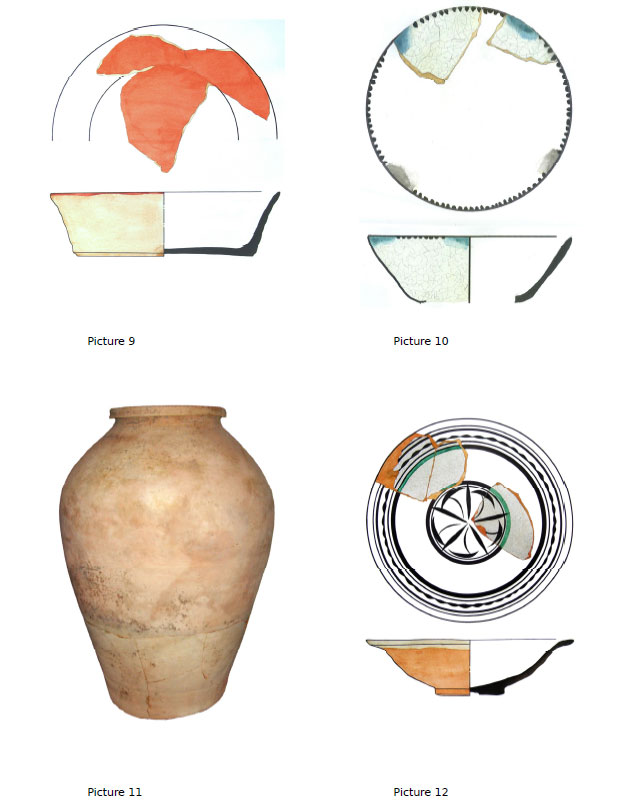

beginning of the 8th centuries AD. The first group does not show

evidence of many types of vessels: it consists mainly of large moulded jars

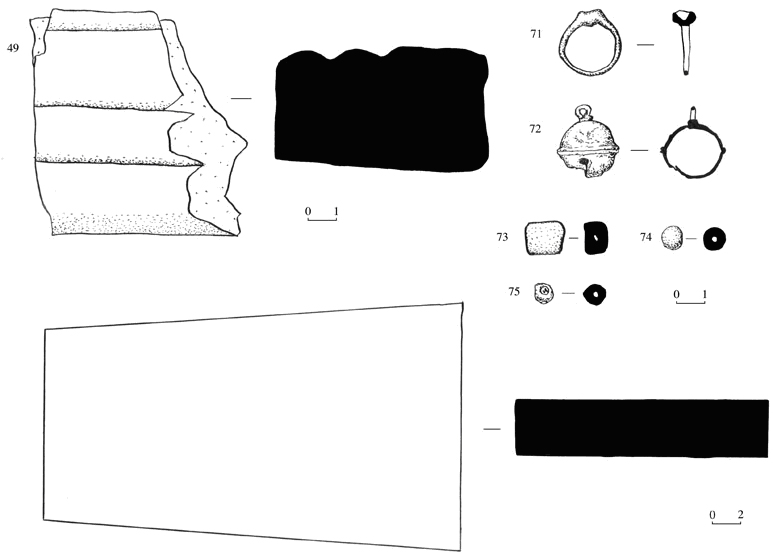

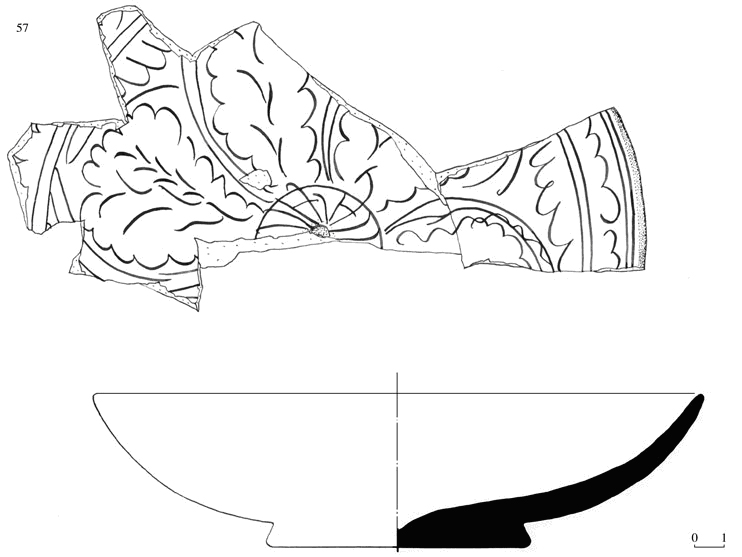

(khum) used for storage purposes (Pl. 1). After analysing the fragments,

we propose that these rough vessels were formed by an ovoidal body and that

they were often cooked only partially (as suggested by the variable colour,

reddish-greenish). In some cases, the external surface presents a white slip on

which a red or black slip is applied forming irregular streaks along the body.

The rims are barely protruding and the necks, not pronounced, are usually

decorated with one or two rows of finger marks (straight or oblique). These

decorations are typical of the Kaunchi pottery,

in particular with the production of the 4th-5th centuries

AD. The nomadic culture of Kaunchi was widespread in the Sir Darya area since

the 2nd -1th centuries BC and survived until the 7th century AD influencing the ceramic production of the neighbouring regions such

as the Bukhara oasis, where the pottery of this type is called of ‘Kizil Kir’

type.

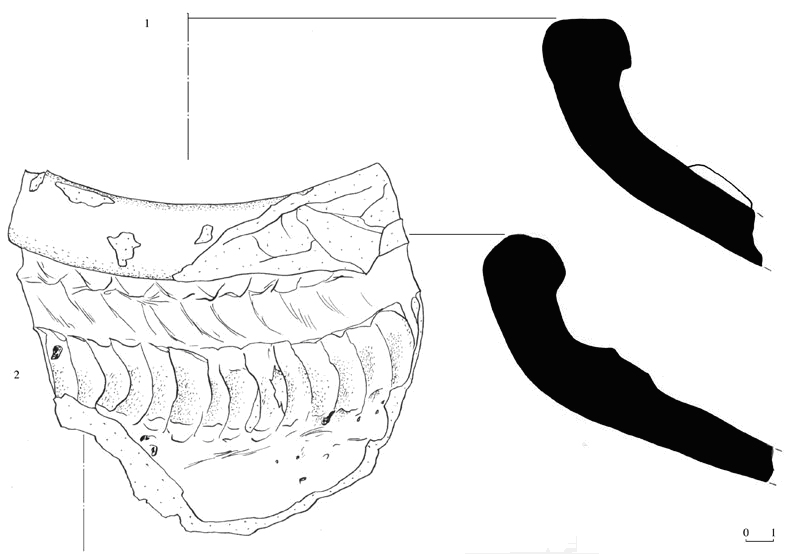

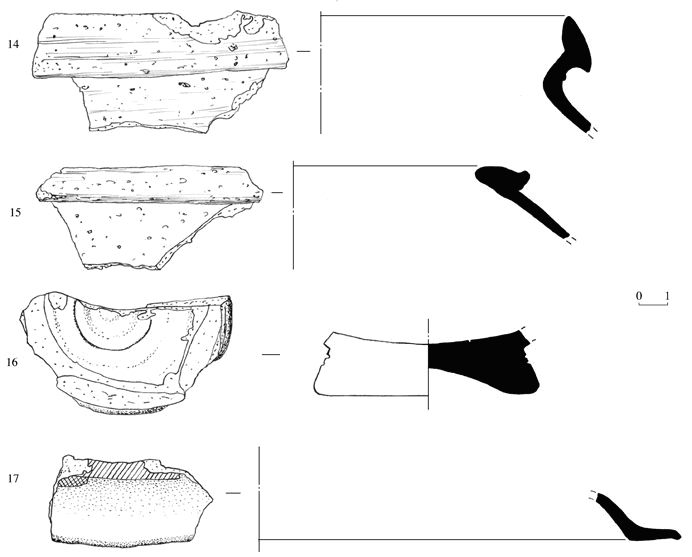

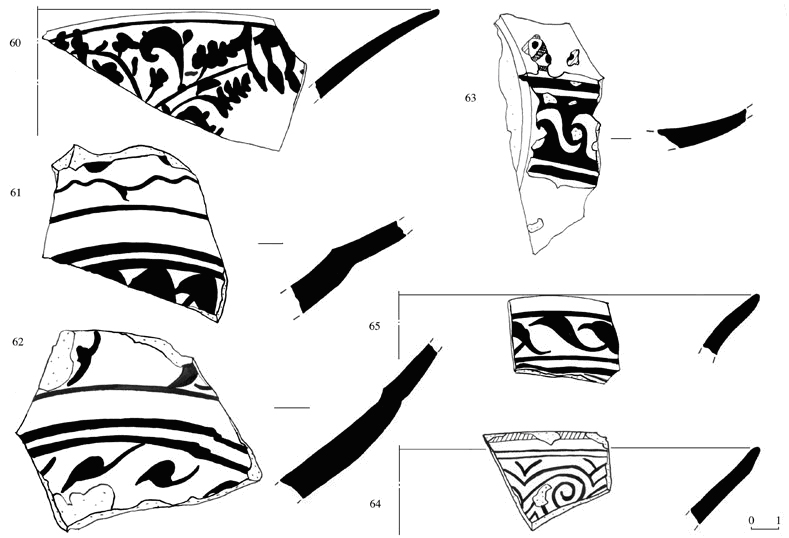

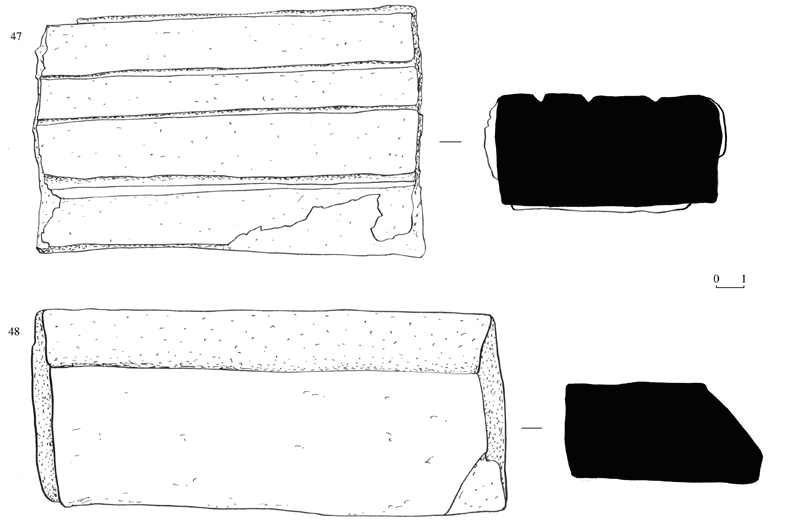

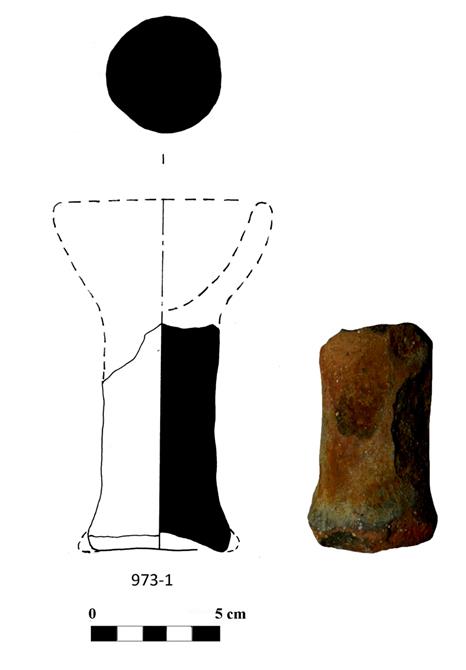

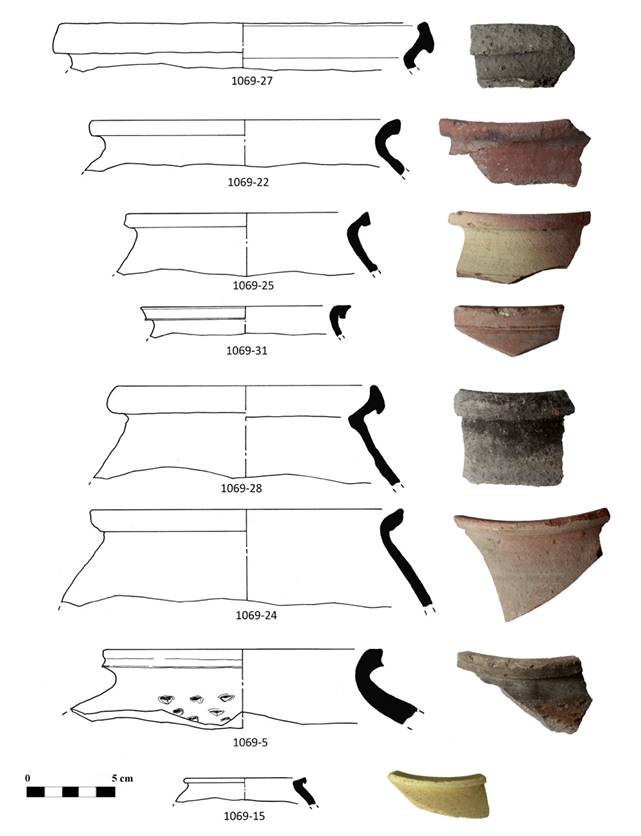

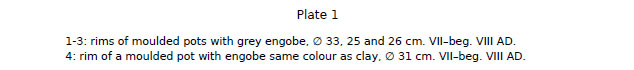

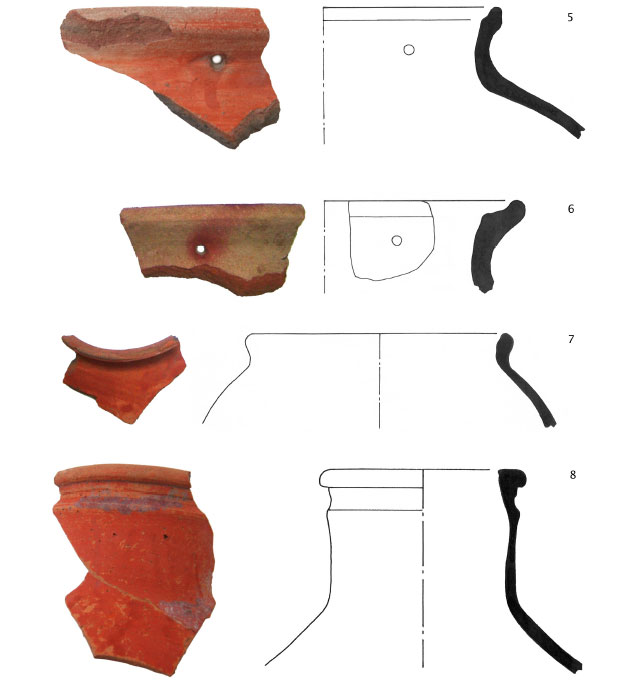

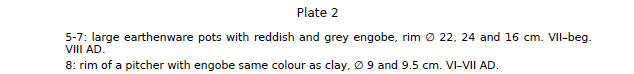

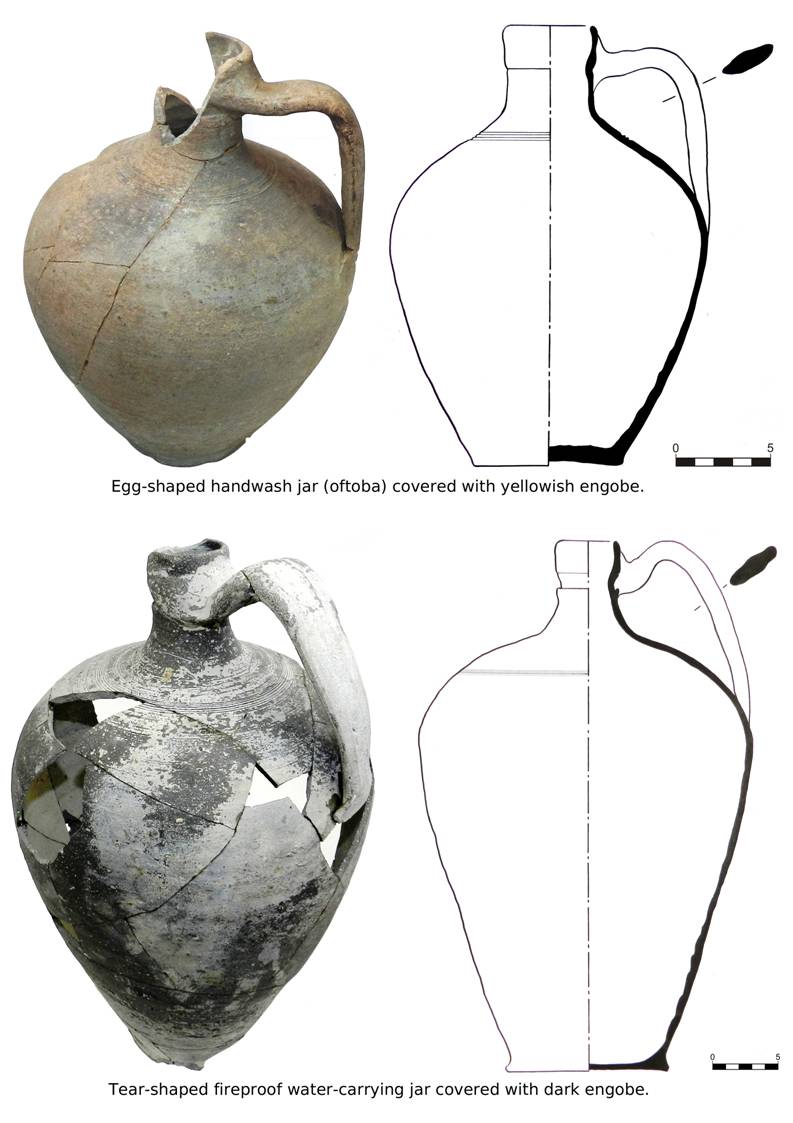

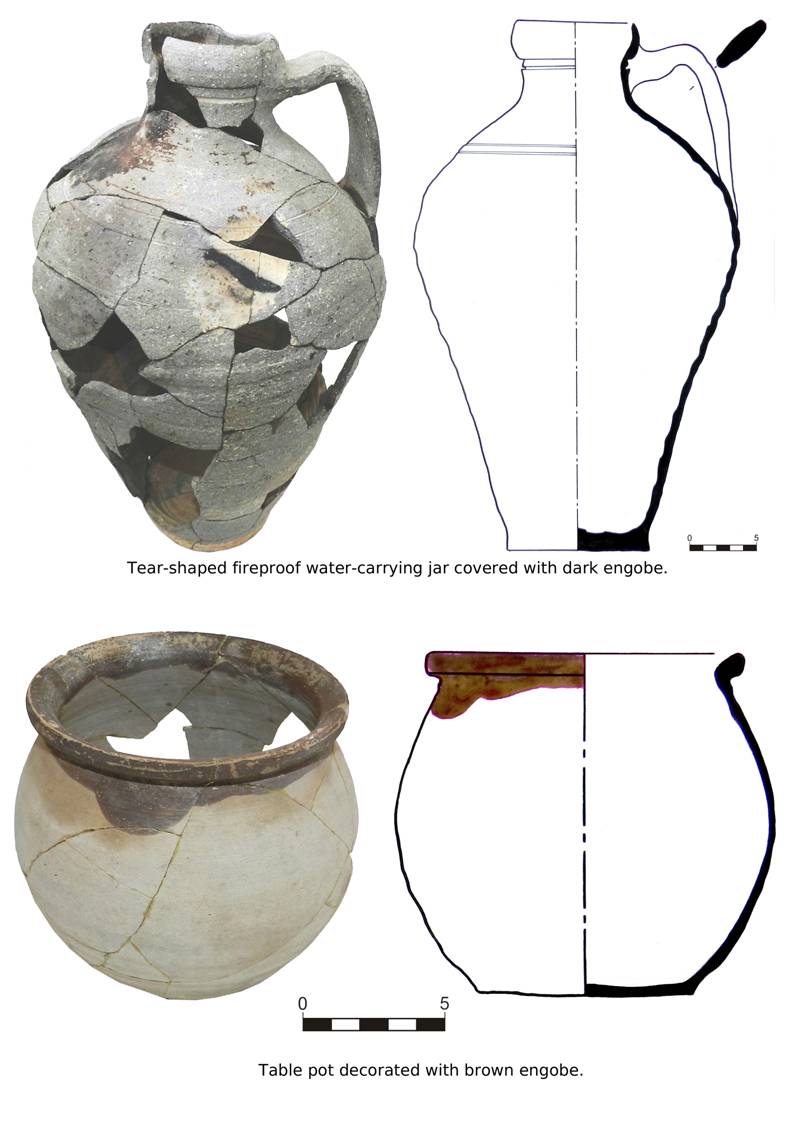

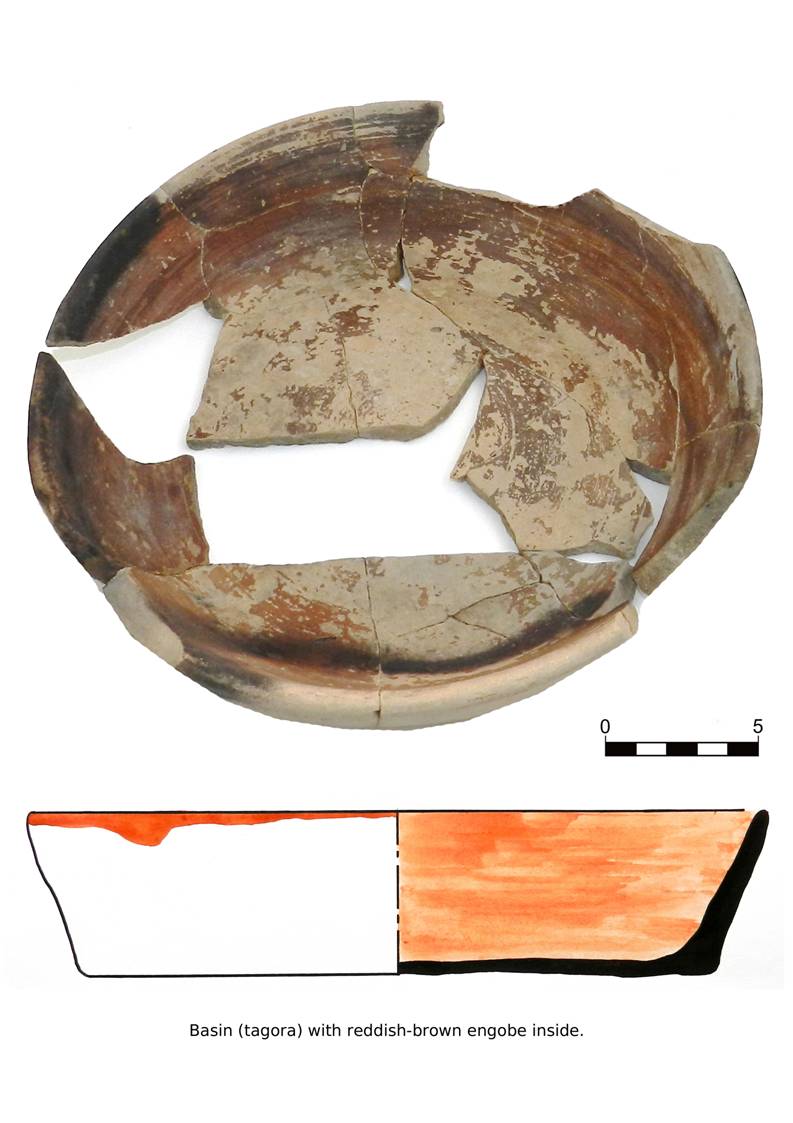

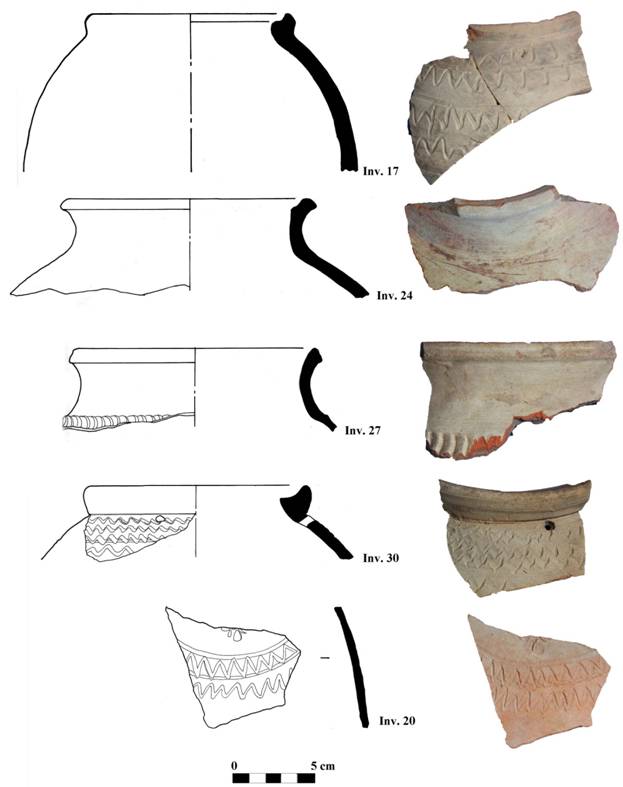

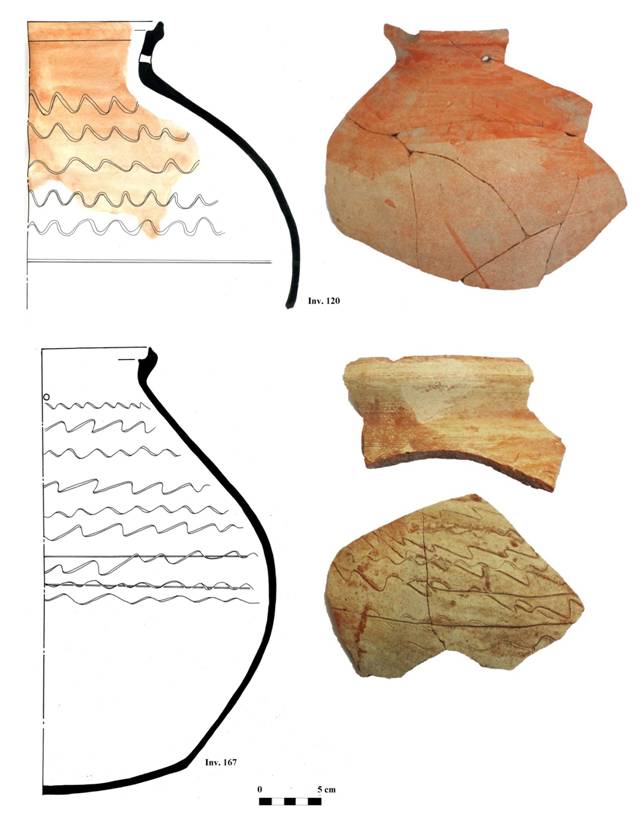

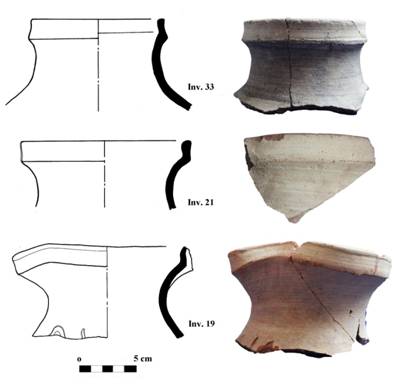

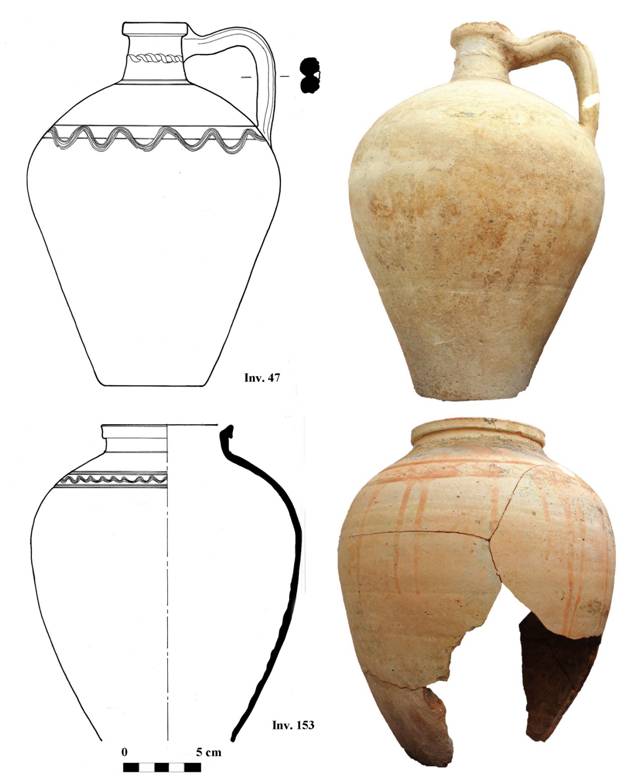

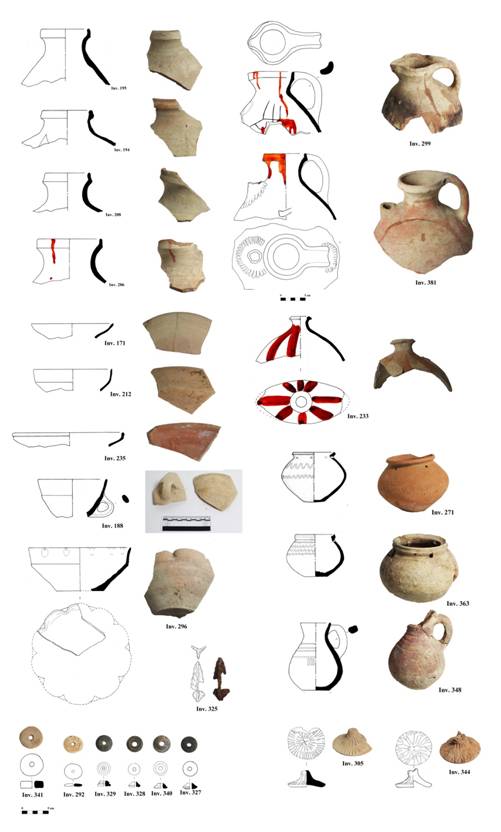

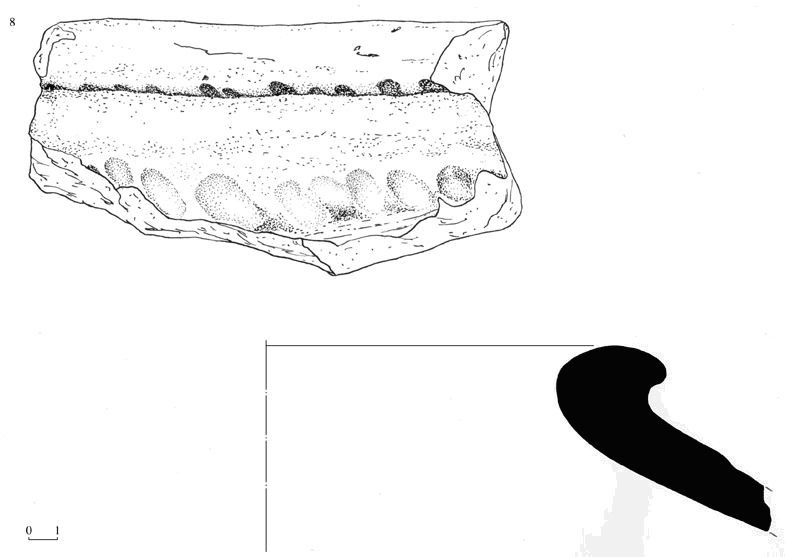

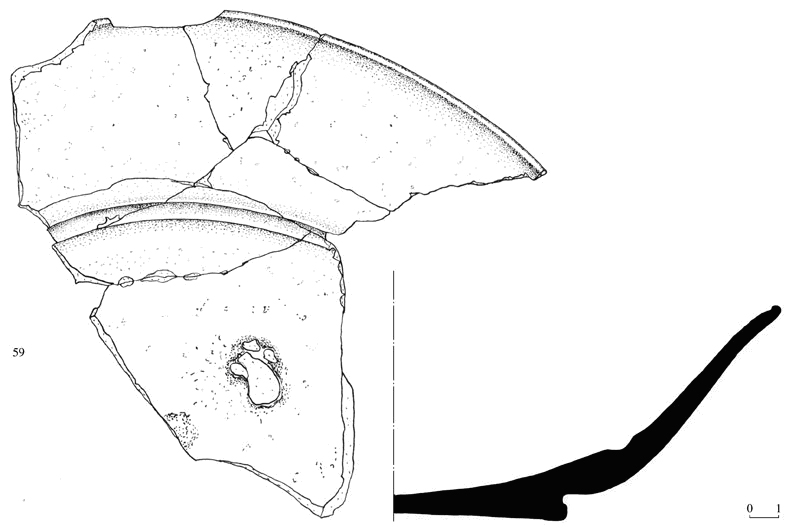

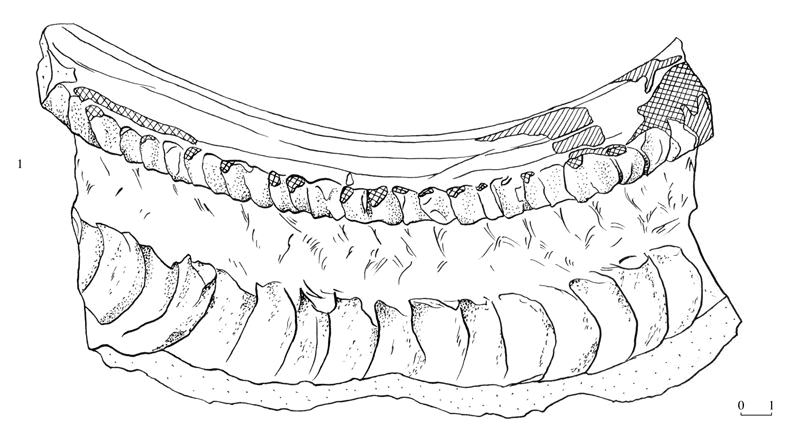

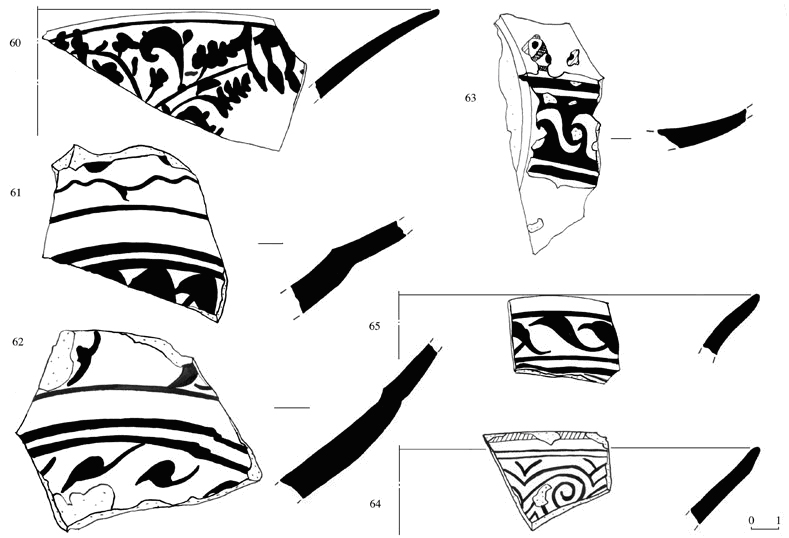

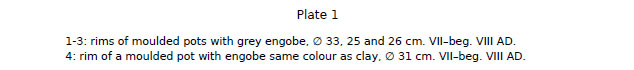

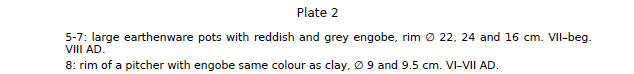

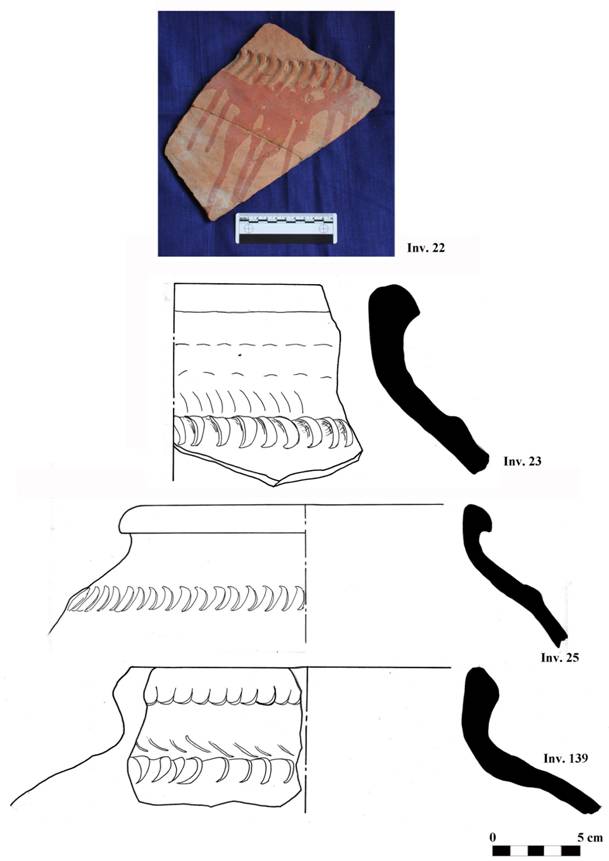

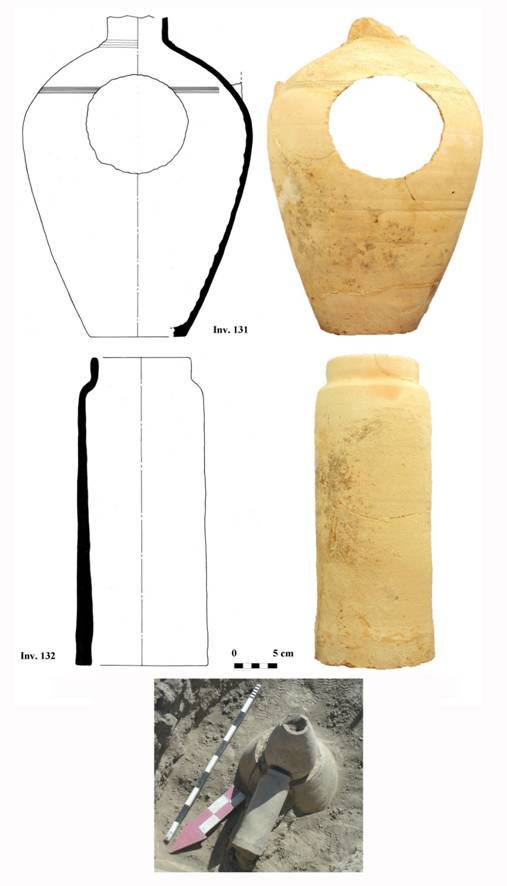

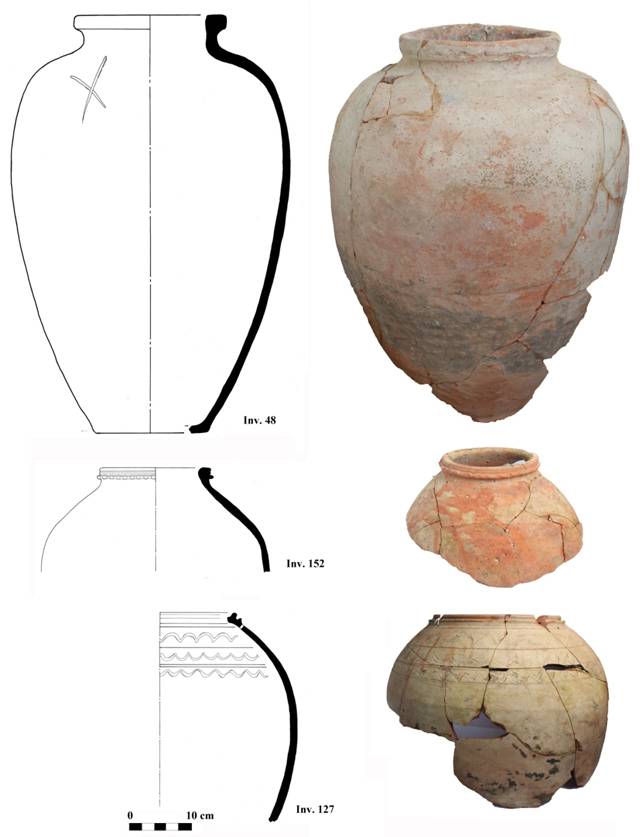

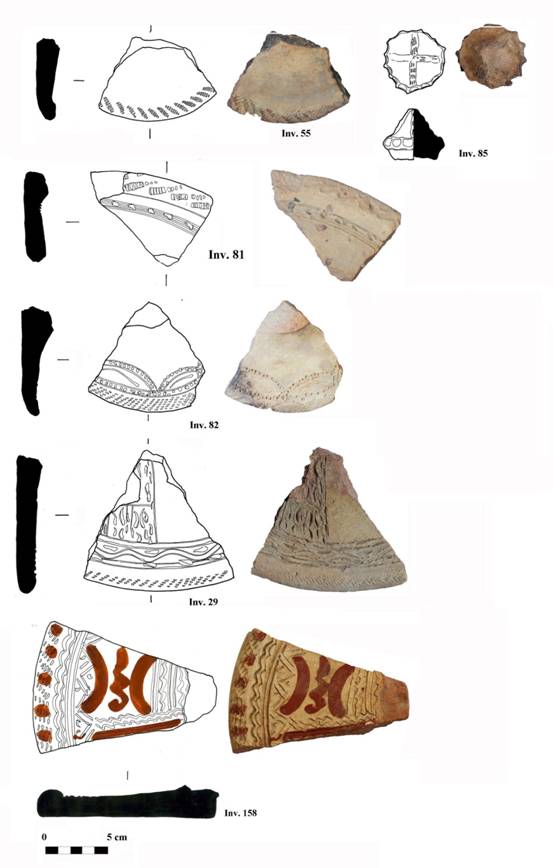

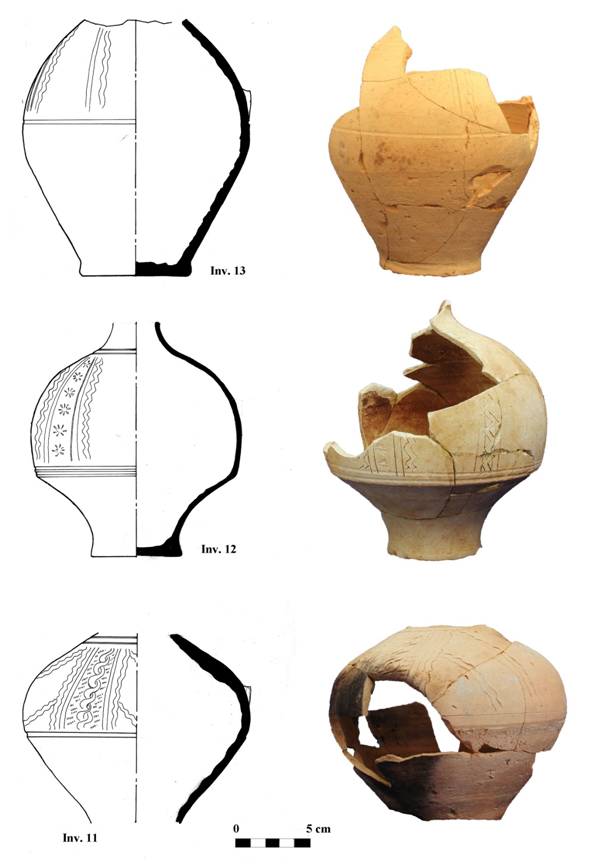

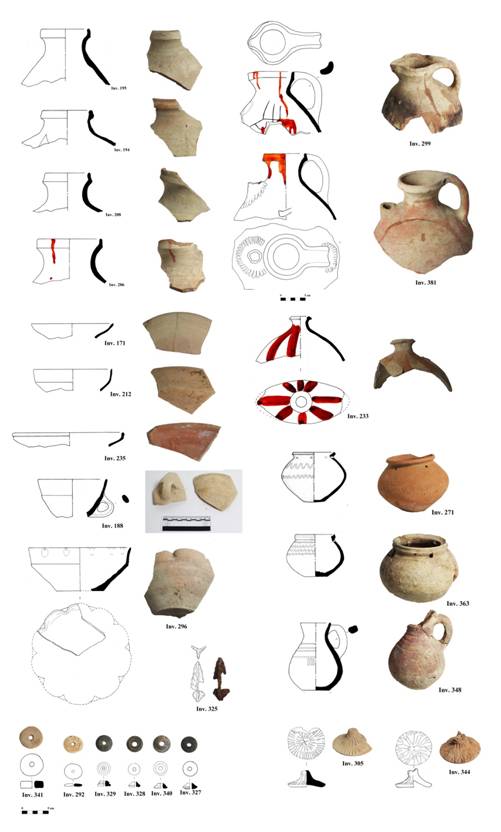

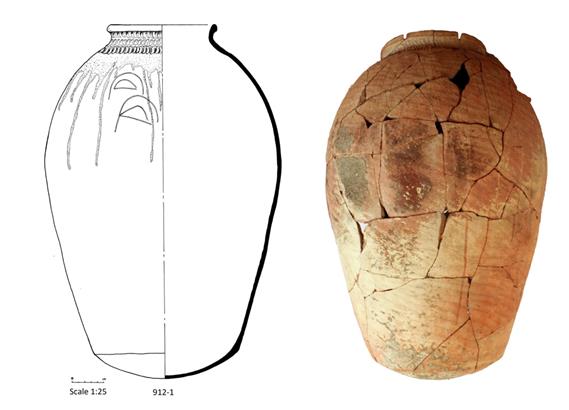

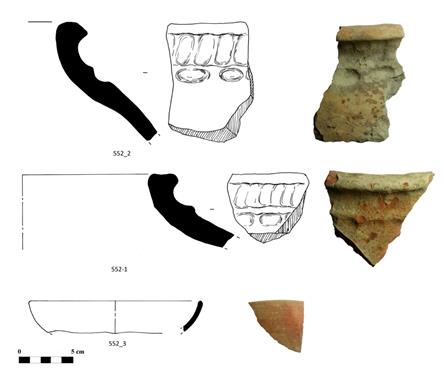

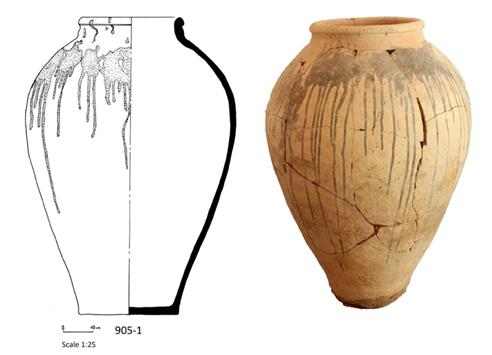

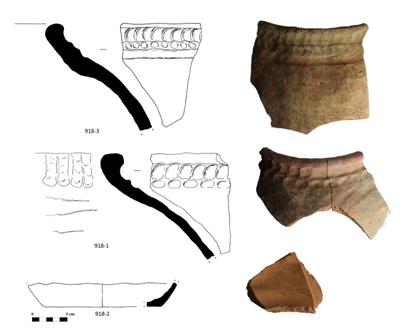

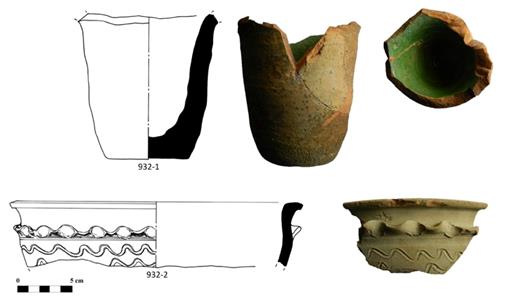

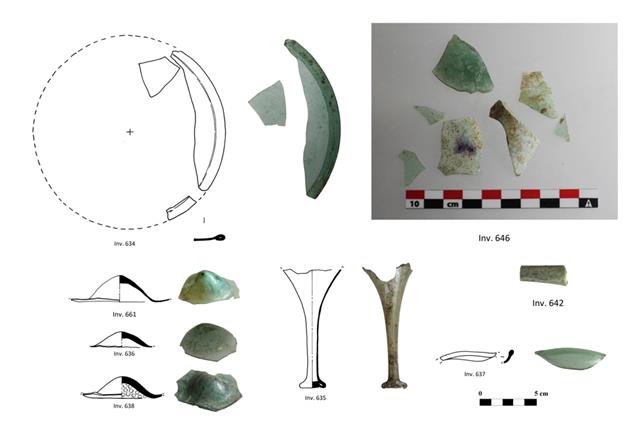

The second Early

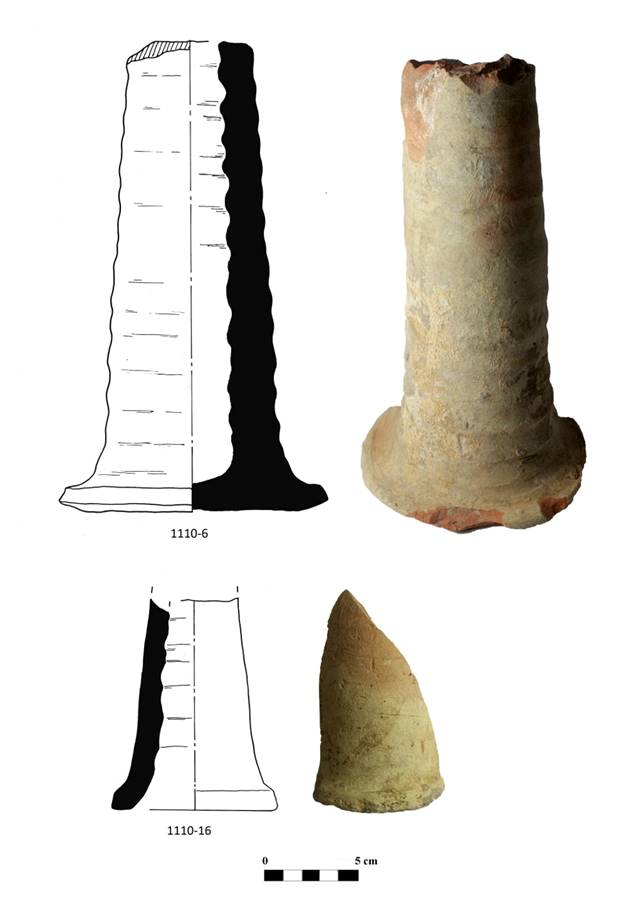

Medieval complex (second half of the 7th- beginning of the 8th centuries AD) presents a more diversified range of shapes, among them large

and small khums, pots, jugs used for household purposes, cups, basins and

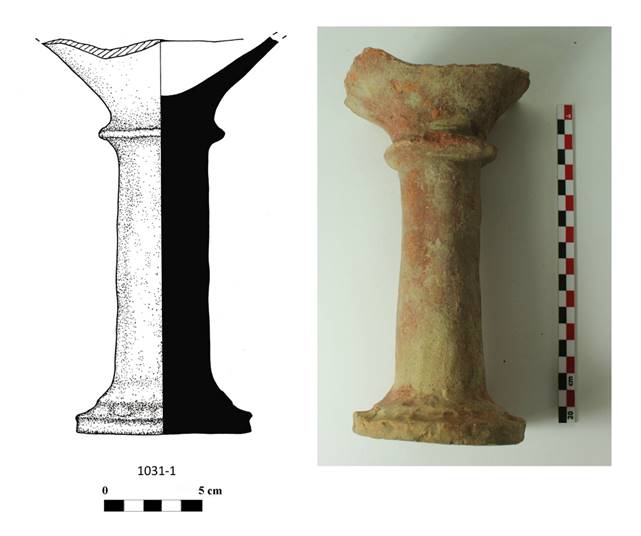

goblets (Pl. 6). Many of the larger khums were prepared on a

potter’s wheel and the rims present rounded or triangular sections (Pl. 2).

The necks, more pronounced than in the preceding pottery, are decorated by

finger impressions and elongated incisions, slightly oblique. In

the smaller vessels the external surface is often covered with a white-yellow

slip and it is decorated with a red slip forming irregular streaks along the

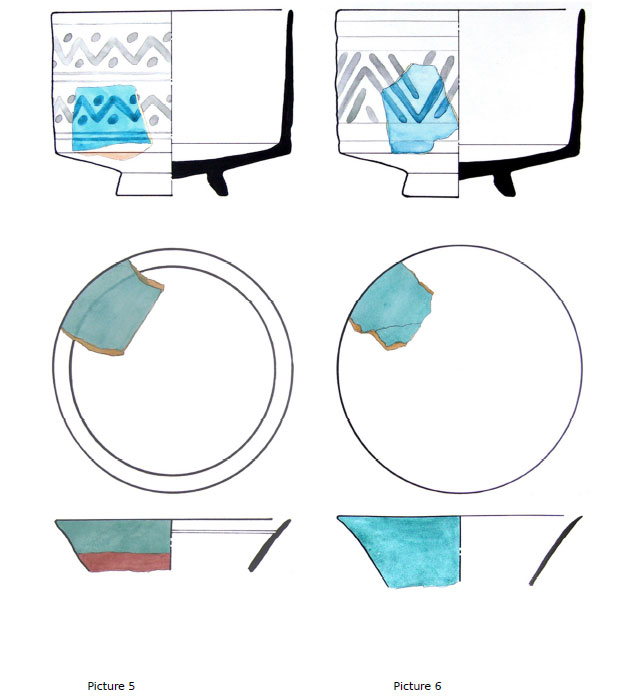

body (Pls. 3-5). The dominant decoration of the small jars, however,

consists in rows of wavy lines (pointed or rounded) incised with a sharp stick,

a well-known motif widespread also in other contemporary Sogdian centres. In

two exemplars of small jars, the rim presents an inset for the lid and the neck

is pierced probably for hanging. Another type of decoration, typical of the

small jars with an reverted globular rim, consists in small oblique dots and

wavy lines incised on the sharp edge between the neck and the shoulder (Pl.

5).

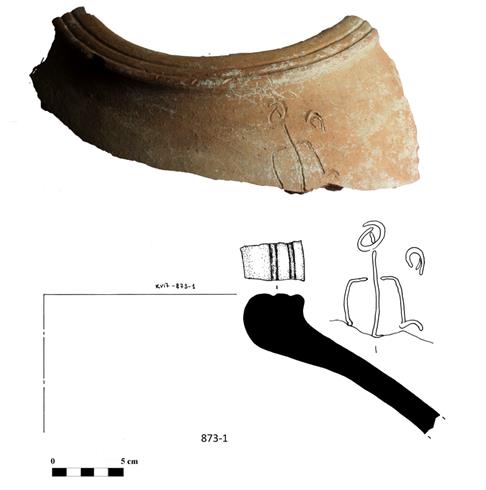

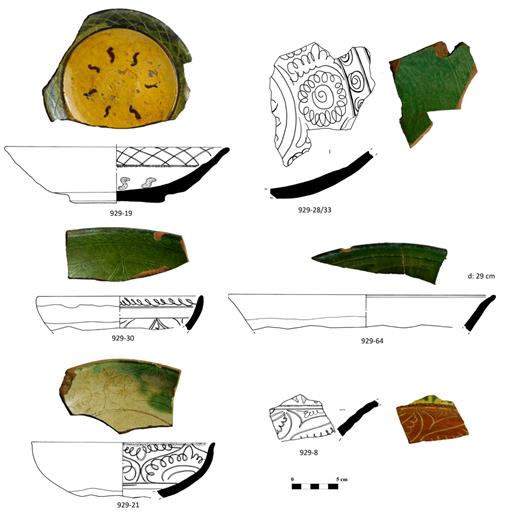

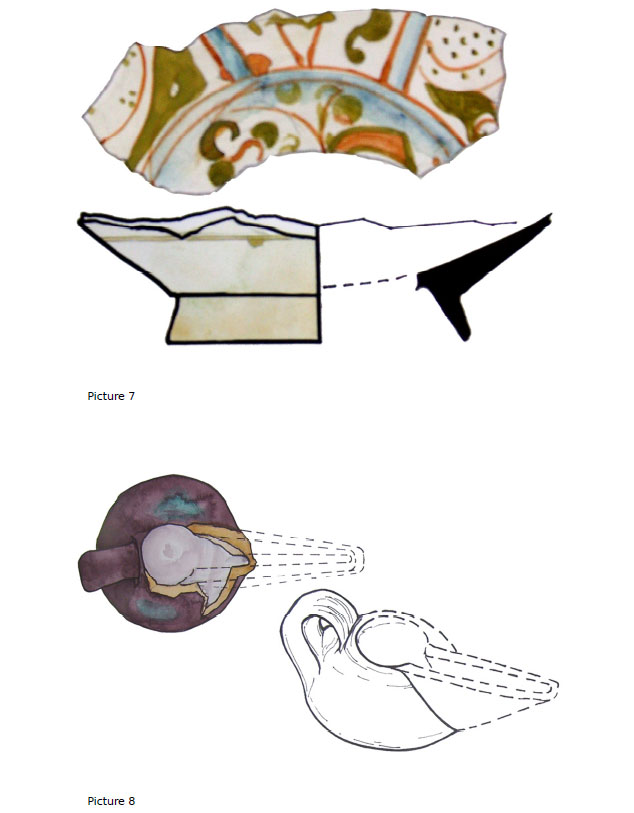

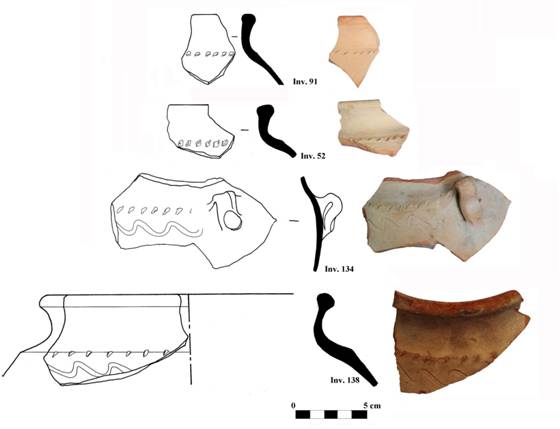

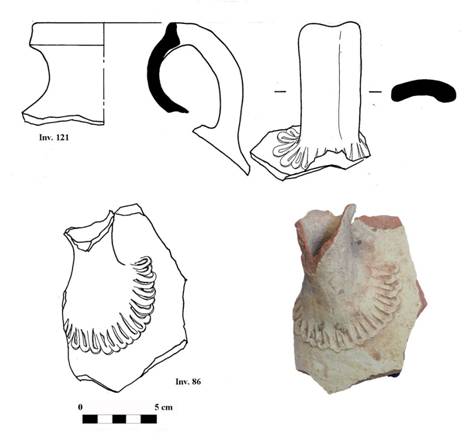

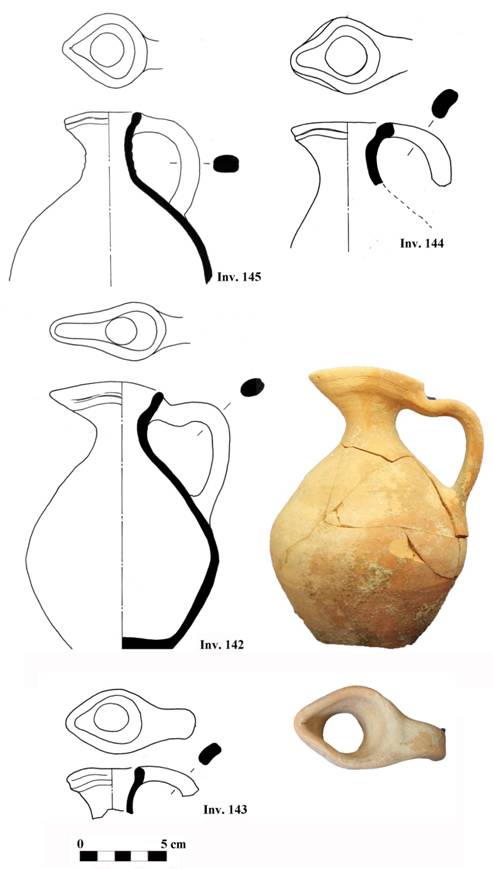

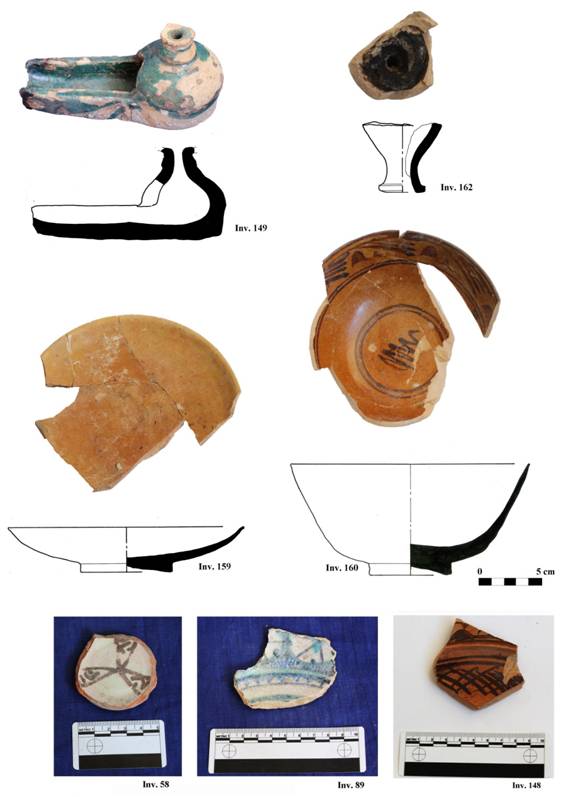

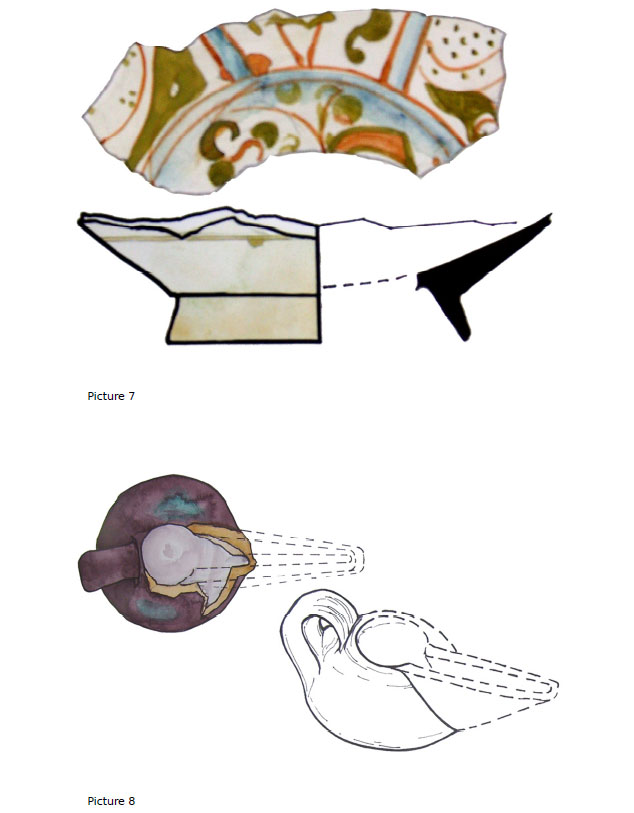

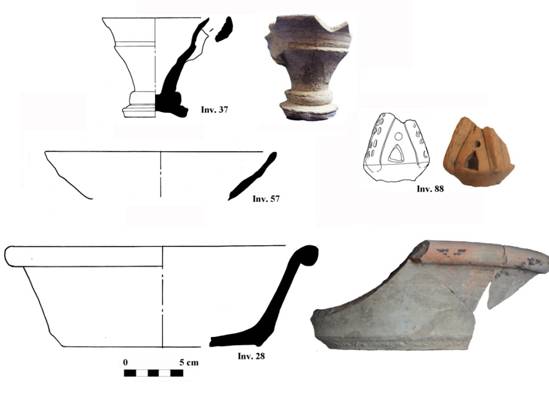

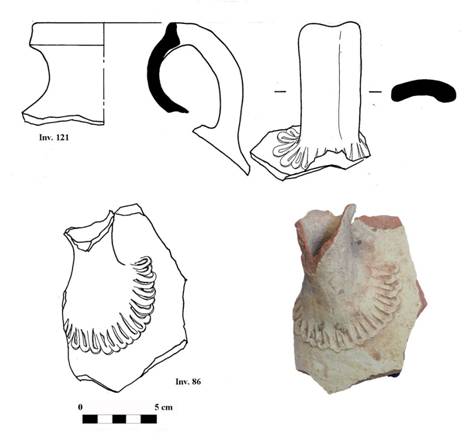

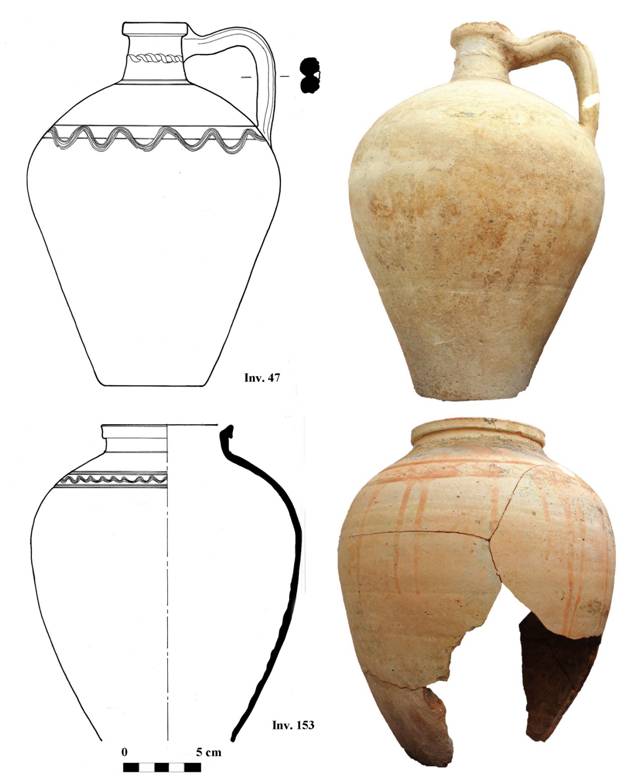

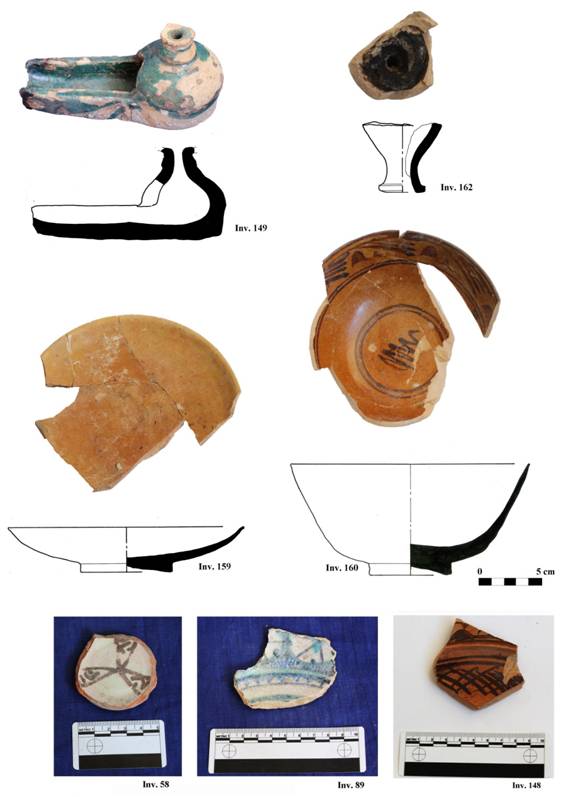

Several examples

of jugs were recovered this year. The jugs may or may not have a handle and

they are usually made with a pale reddish clay, covered with a white slip (Pl.

7). The beak (Ø: 11-14 cm ca) presents a straight rim with rectangular

section, slightly concave on the external side. In one exemplar, a petal-like

ornament decorates the bottom part of the handle and of the spout located under

the neck (Pl. 8). It is probable that this particular decoration,

unknown before, represents a peculiar local motif. Lastly, the discovery of

some fragments of ‘oinochoe-like’ juglets deserves to be mentioned. The juglets

were found all outside perimeter wall 29 (Pl. 9). These vessels are made

of a light red-orange clay and they are decorated with a fine white-red slip.

To conclude, we

can recognize two different trends in the local pottery production between the

6th and the 8th centuries AD. The first one is based on

the classic Sogdian tradition and it presents close analogies with the

contemporary complexes of the whole Sogd. The second type of production,

technically inferior, was influenced by the Kaunchi culture, as shown by the

recurrent ornamental features. If we compare the local Early Medieval pottery

with the production of the other settlements and villages in the Western Sogd, we

can see a more intense influence of the Kaunchi in the vessels of Vardāna.

It is not surprising, since Vardāna was situated on the borderline between

the sedentary area and the steppe, a territory under the control of the nomadic

populations.

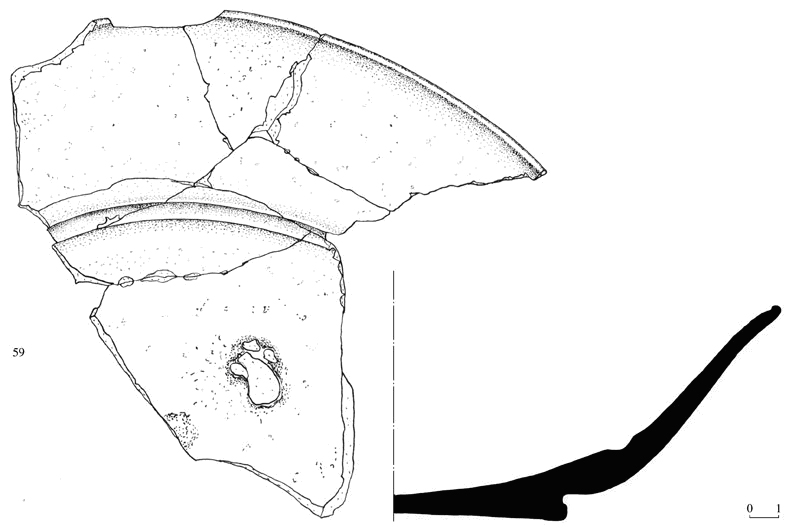

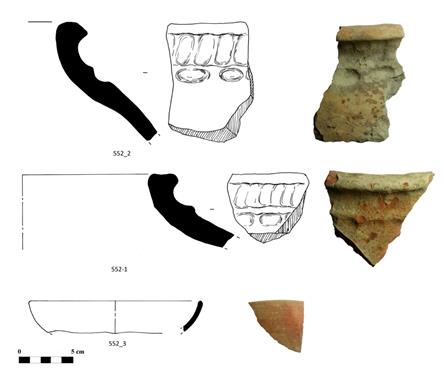

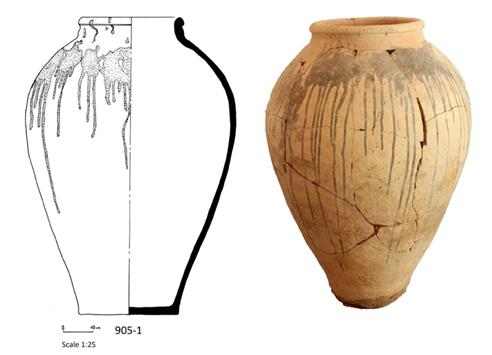

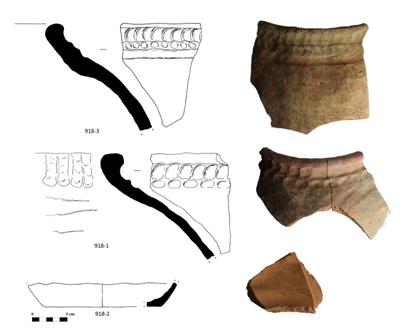

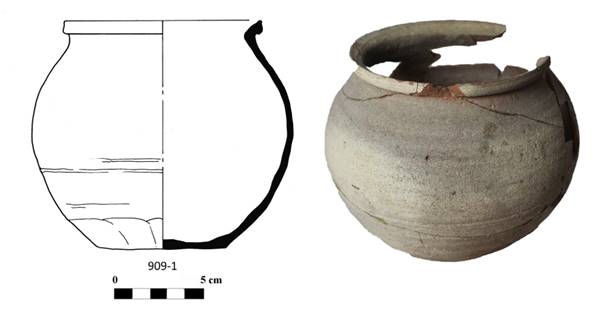

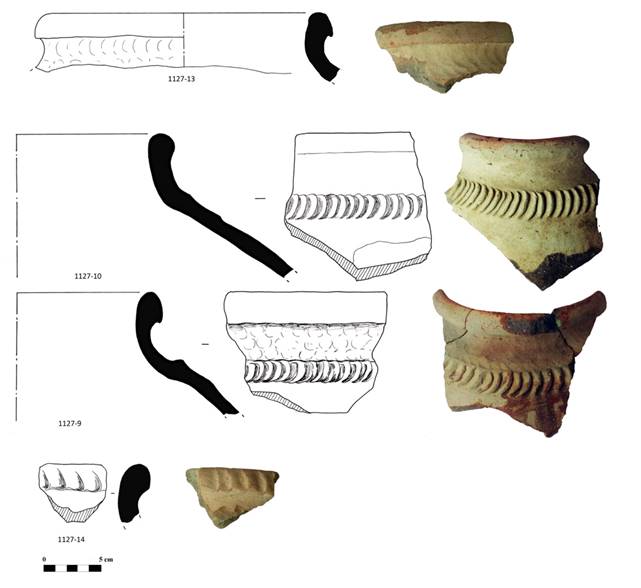

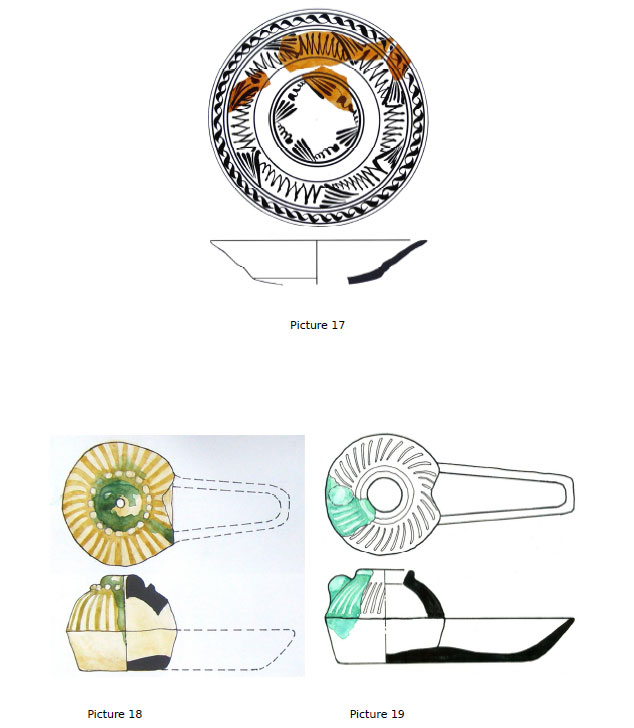

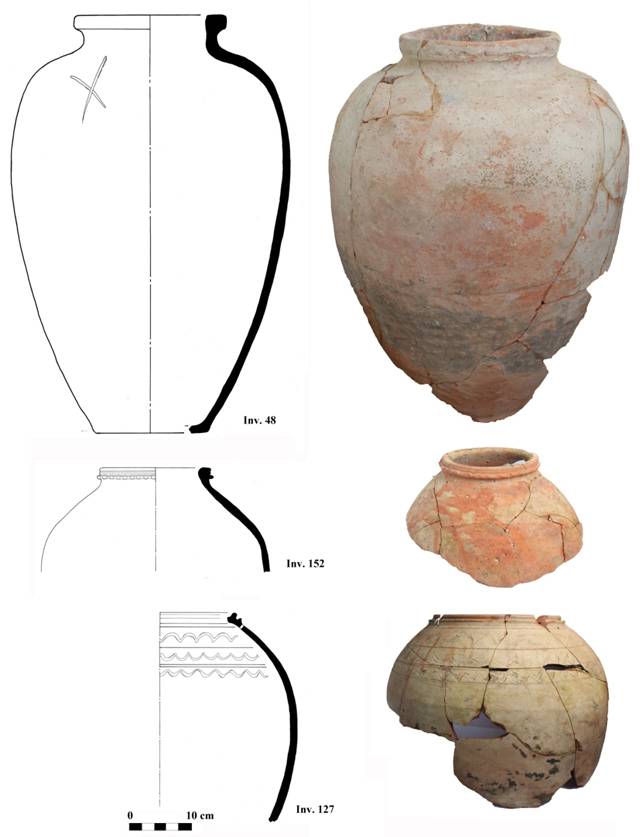

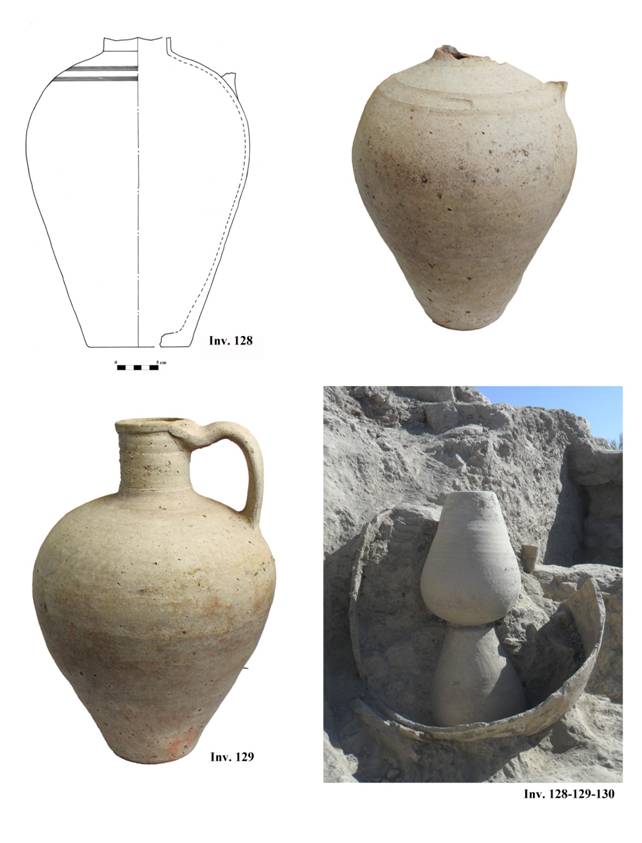

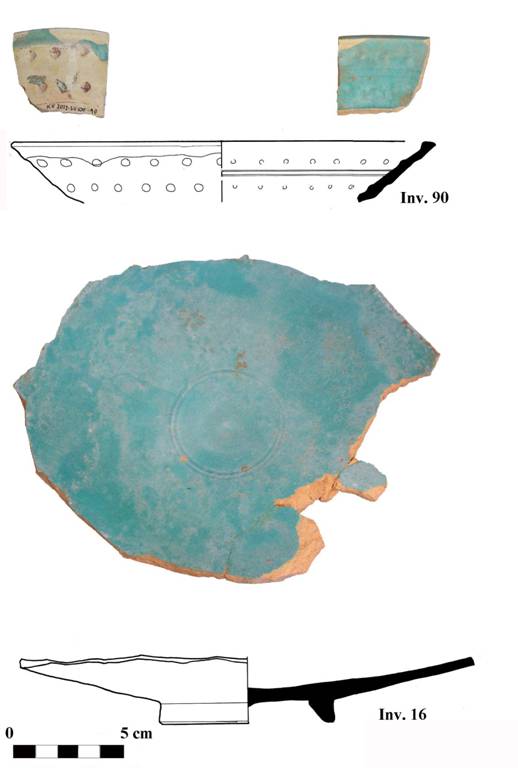

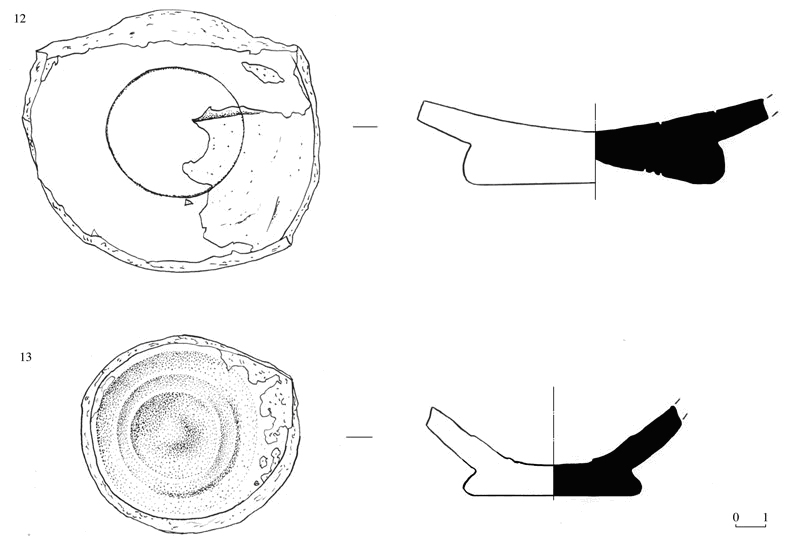

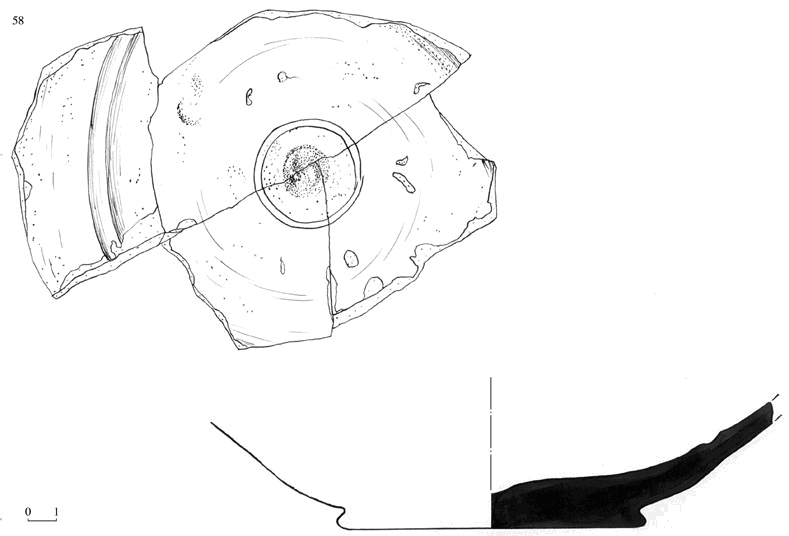

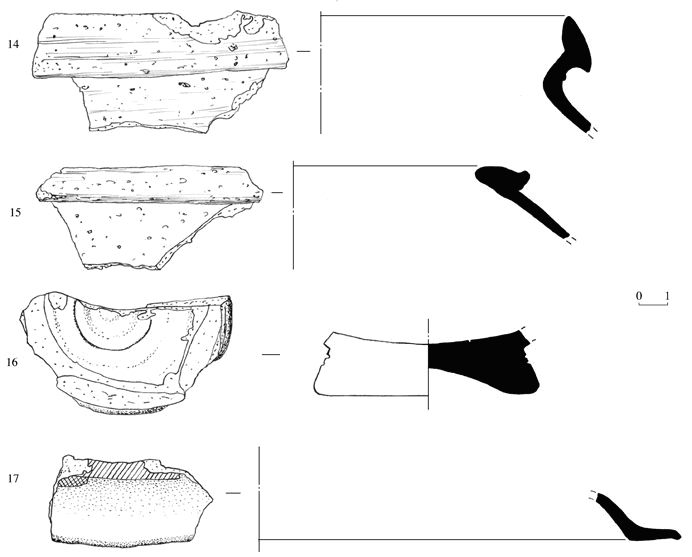

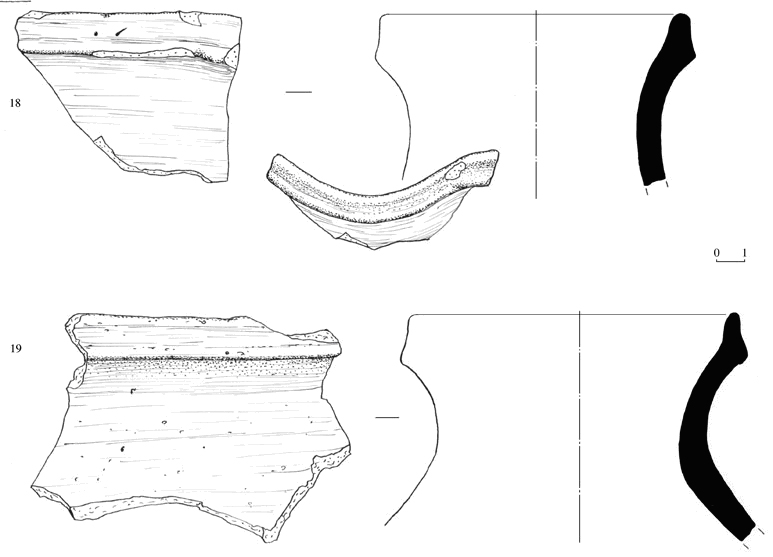

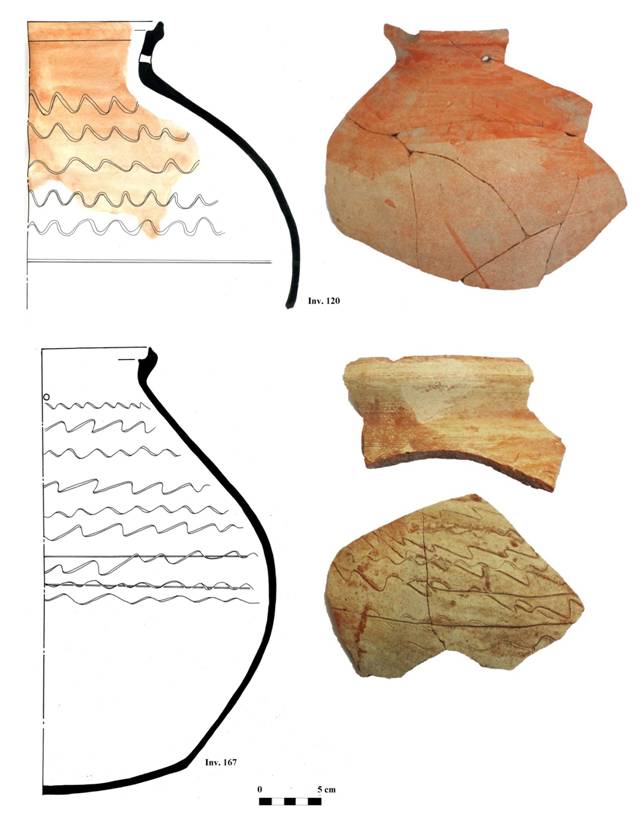

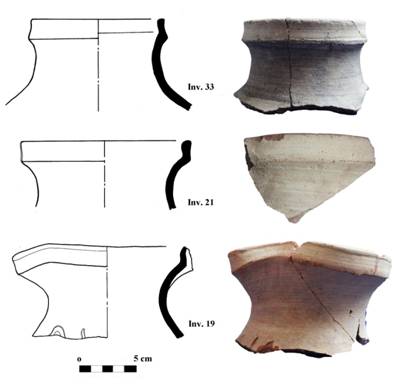

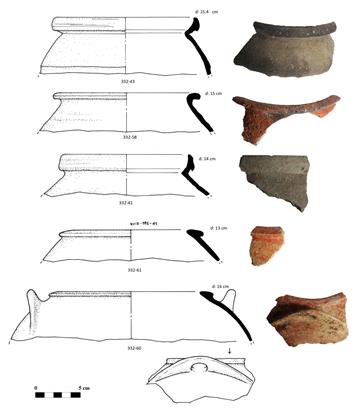

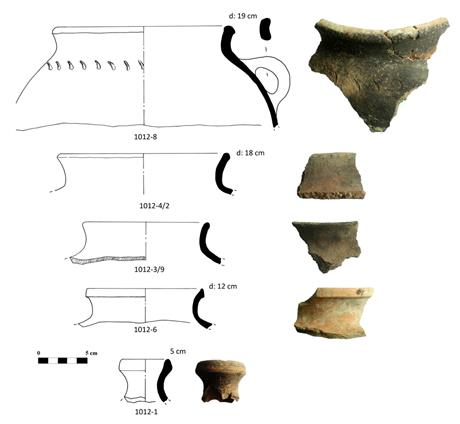

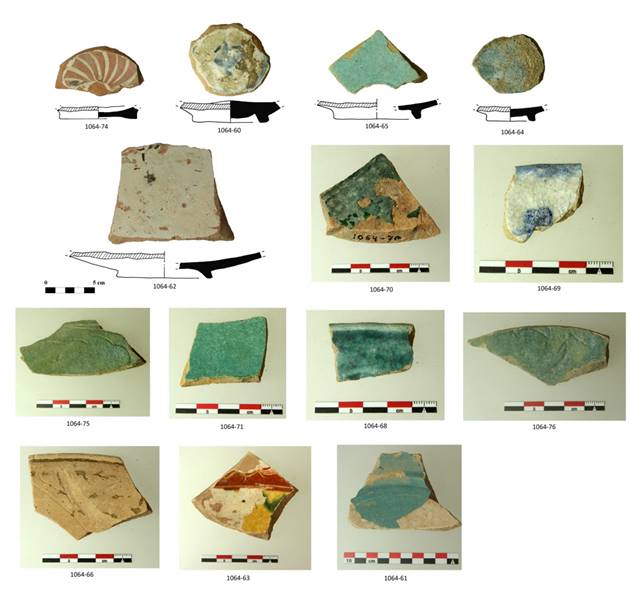

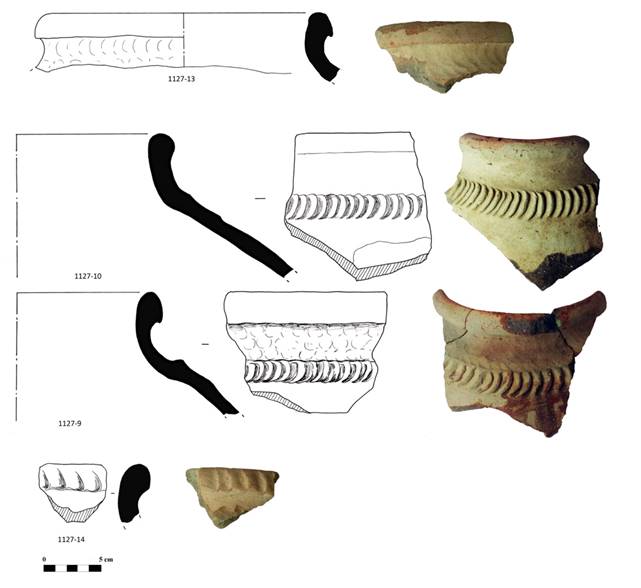

The

chronological complex of ceramics dating to the 12th century AD is

represented mostly by large khums and jugs found superimposed in canalization

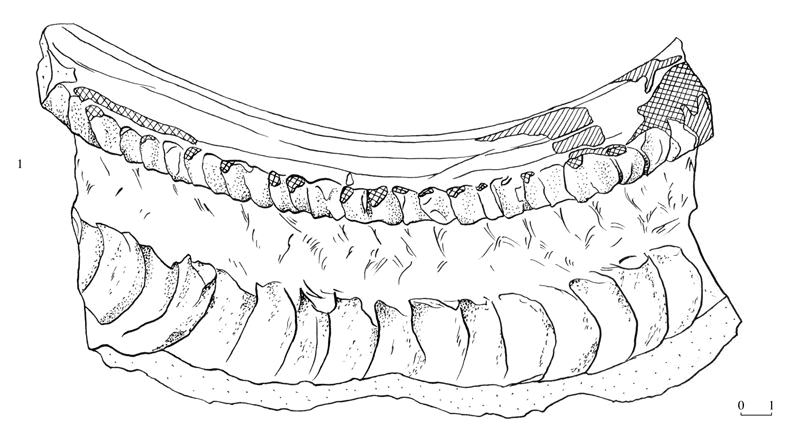

systems (tashnau). The khums are wheel-made and present an ovoid body

often covered with a white slip (Pl. 13). The rim of the larger khums

(Ø: 25 cm) is usually straight while in the smaller vessels it presents an

inset for the lid or an external groove, probably used for functional purposes

(to tie a fabric used as lid?) (Pl. 15, inv. 127-152). The rims are

usually not decorated, or otherwise they present a simple ribbon motif. Incised

or stamped decorations are generally concentrated on the shoulder, in form of

concentric lines or wavy motifs. The latter design, still in use since the

Early Medieval period, is then more stylized and approaches comb-like patterns

(Pls. 14-16). Continuity in production can be recognized also in the red

slip applied to the body to form irregular streaks, which remains in use in the

later period.

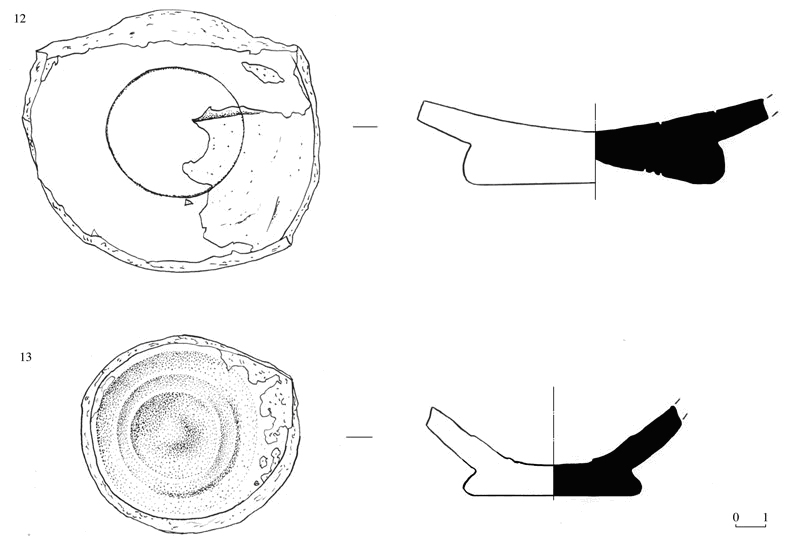

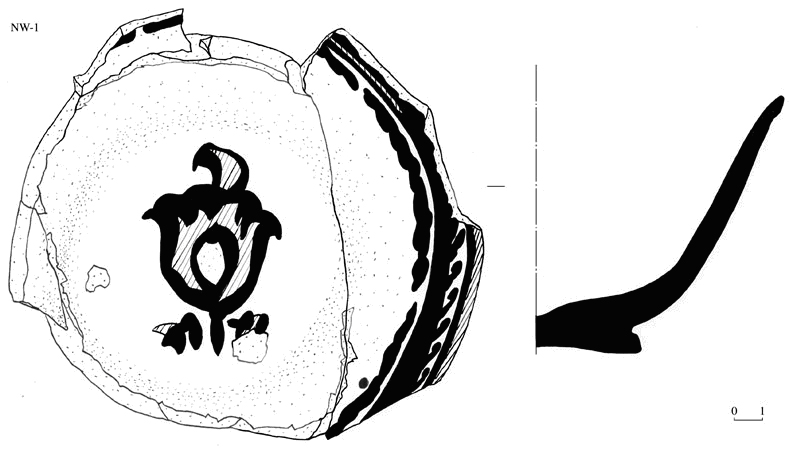

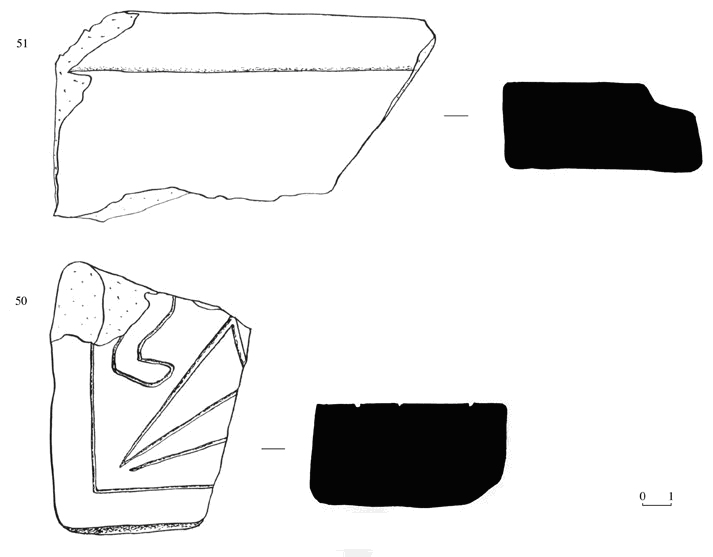

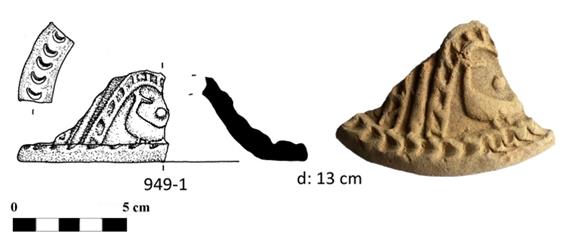

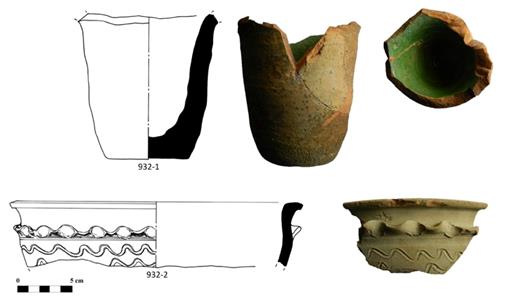

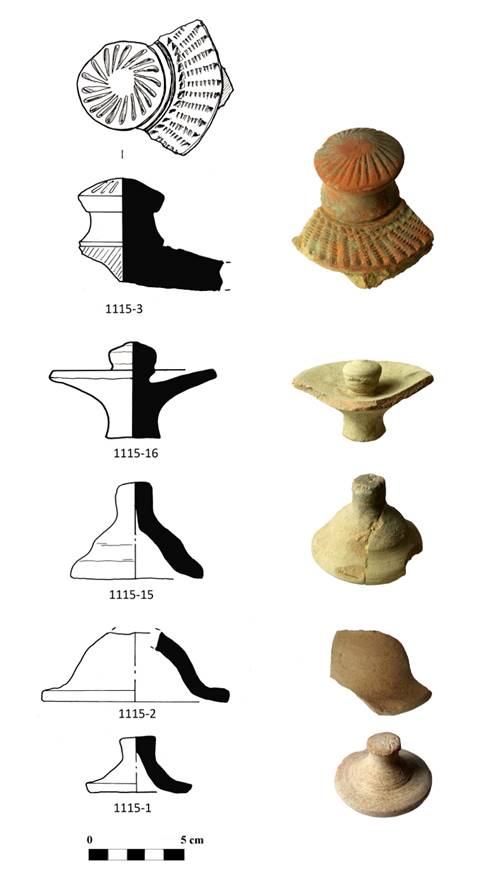

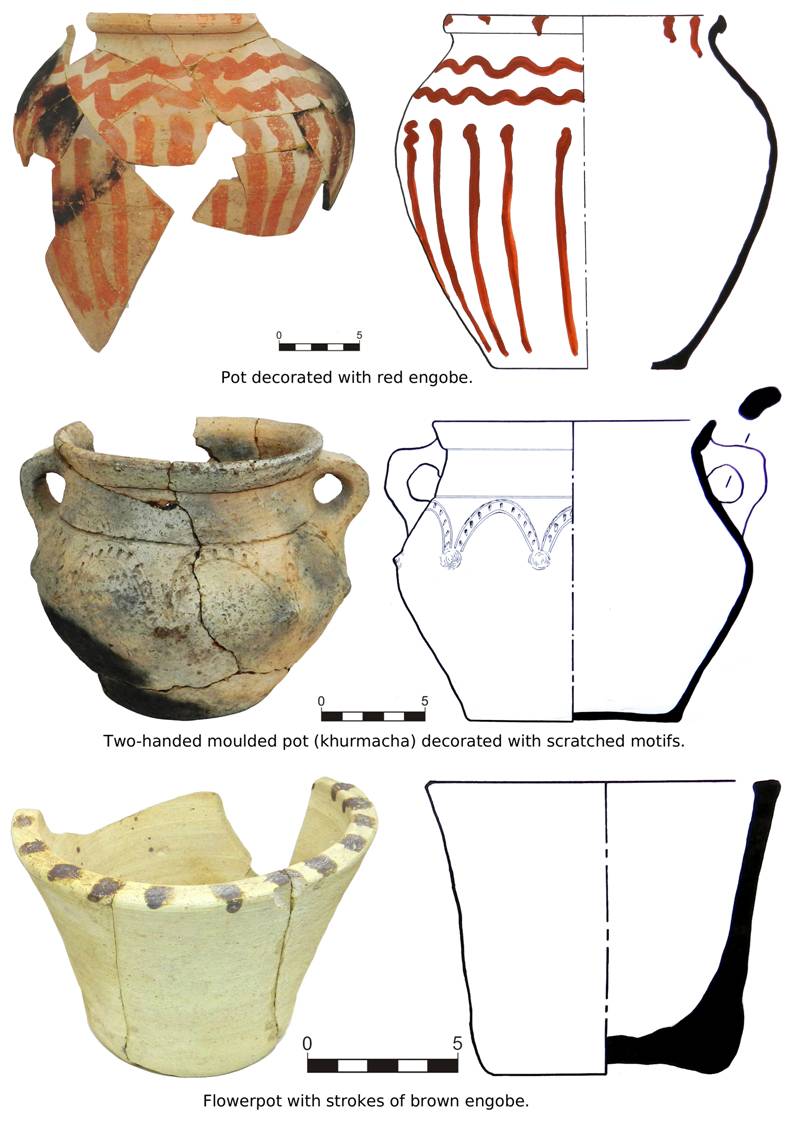

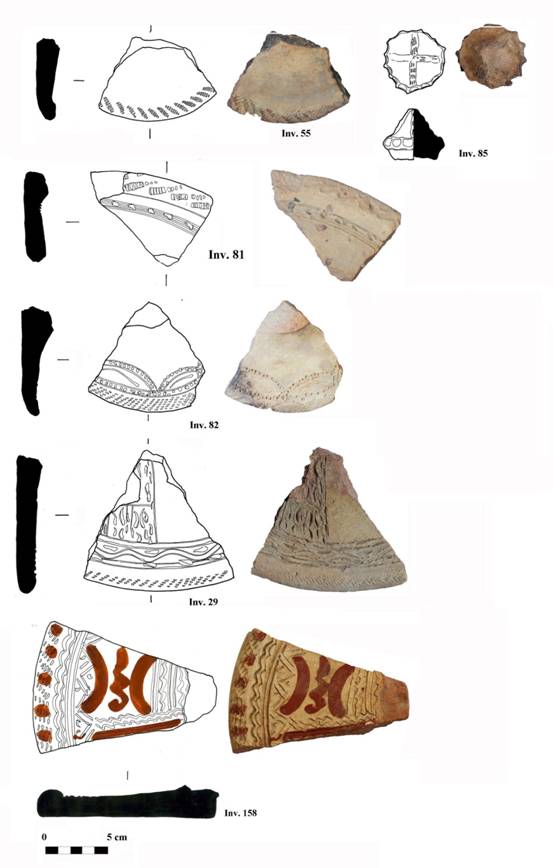

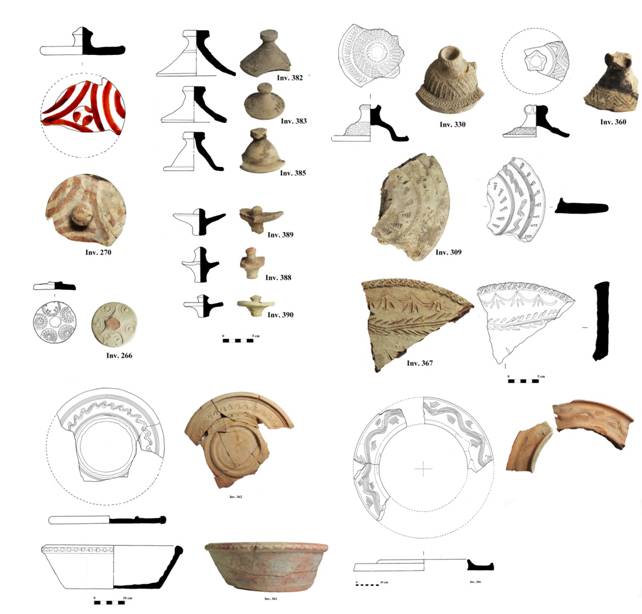

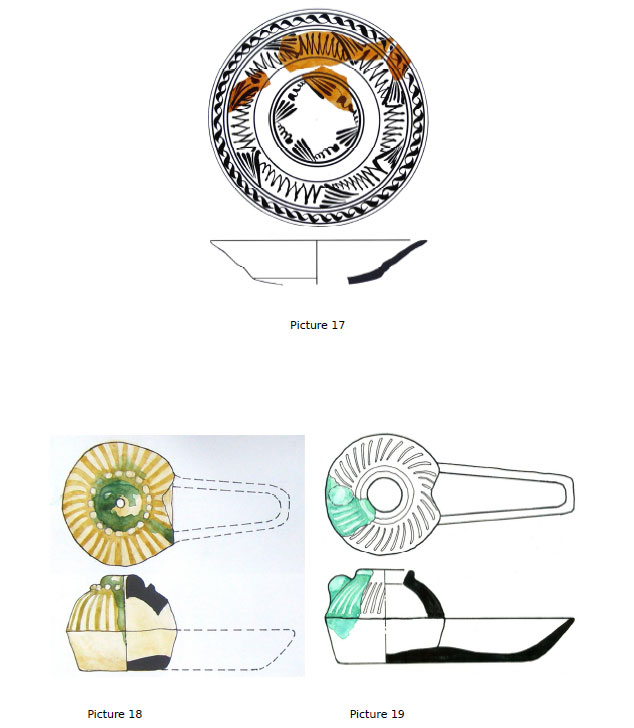

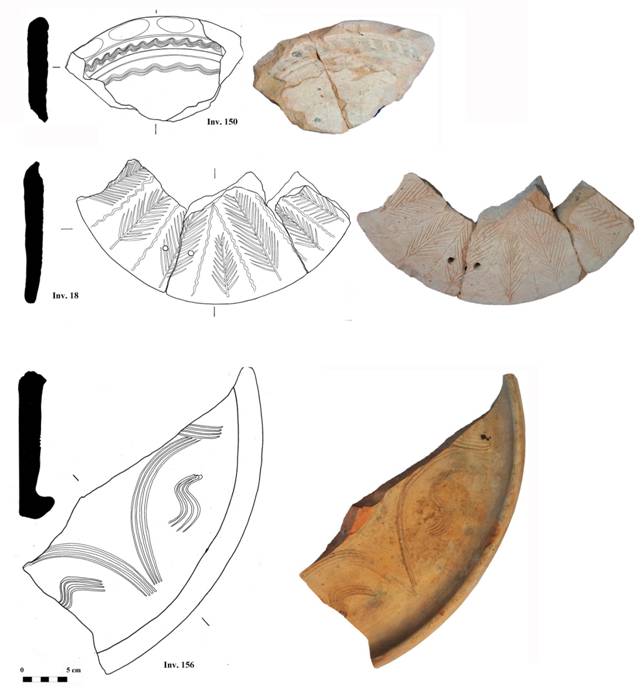

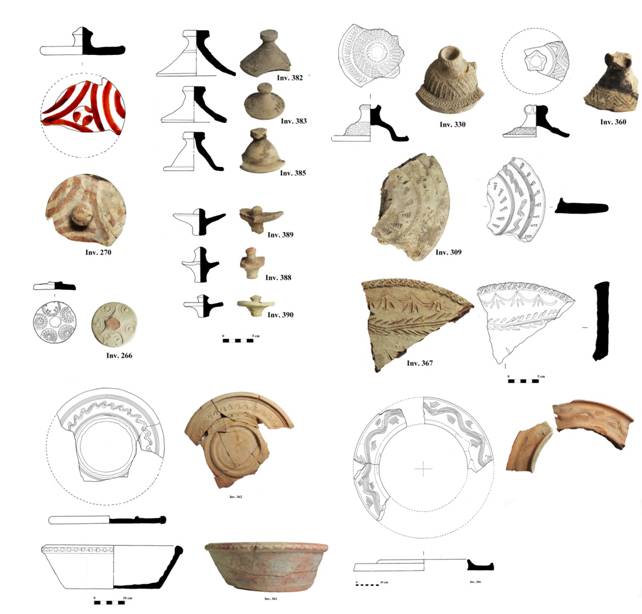

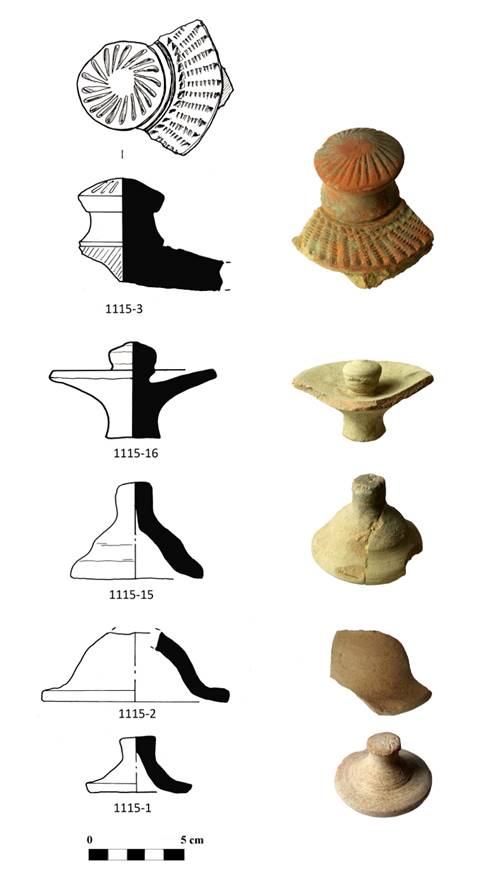

A large

assemblage of lids (Ø: 32-34 cm), mostly wheel-made and used to cover the

jars, has been found (Pl. 18-20). Some of the lids are covered with a

white slip and the surface is decorated with incisions or stamped decorations.

The incised decorations are mainly geometric and stylized, showing similarities

with the motifs on the storage vessels. Among the stamped decorations are both

geometric and elegant vegetal motifs. All the lids date to the 12th century AD, except for a fragment showing an incised tree-motif (Pl. 18,

inv. 18). This lid could be earlier, as suggested by some ceramics from

Paykend, which are characterized by a similar motif called the ‘tree-of life’. It is

interesting to note that this decoration is also very common on the ossuaries

from Sogd and the neighbouring regions.

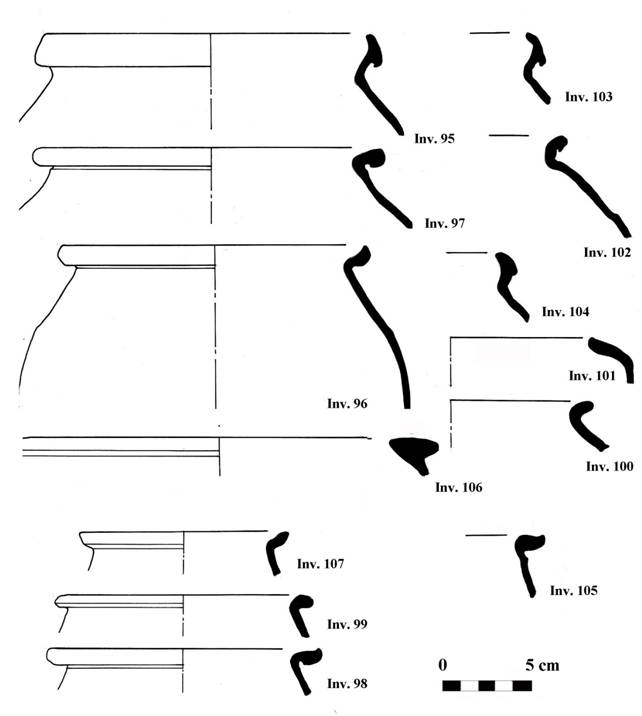

A large

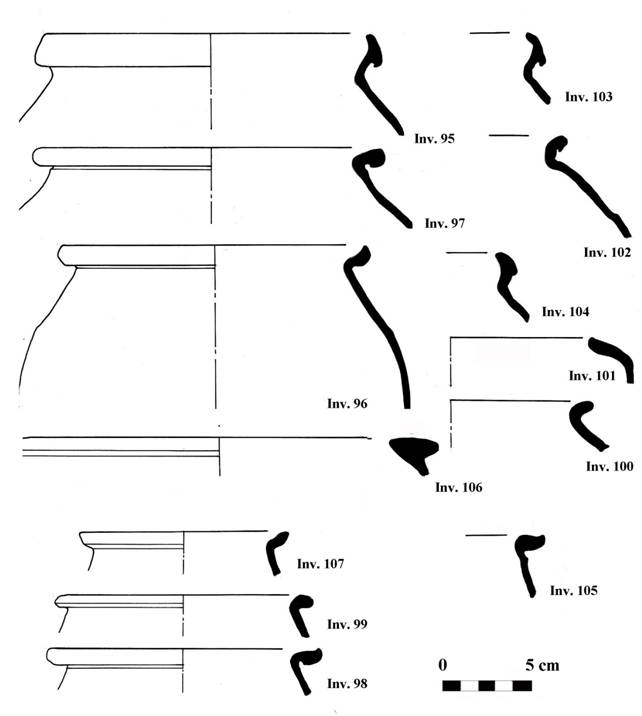

assemblage of cooking pots has been found inside pit hole SU 100 (room 7).

Most of the vessels are wheel-made and do not carry any decoration (Pl. 11).

The clay contains small inclusions and the predominant colour is grey. The rim

shards (Ø: 13-20 cm) can be divided into four general groups even if they are

irregular: inverted rims with an elongated section (Pl. 11, inv. 95, 103,

104); reverted rims with round section (Pl. 11, inv. 97, 99, 100);

reverted rims with an inset for the lid (Pl. 11, inv. 96, 107); reverted

rims with a flattened upper part (Pl. 11; inv. 98, 105, 106). A

particular inverted rim with vertical body has also been found (Pl. 11, inv.

101).

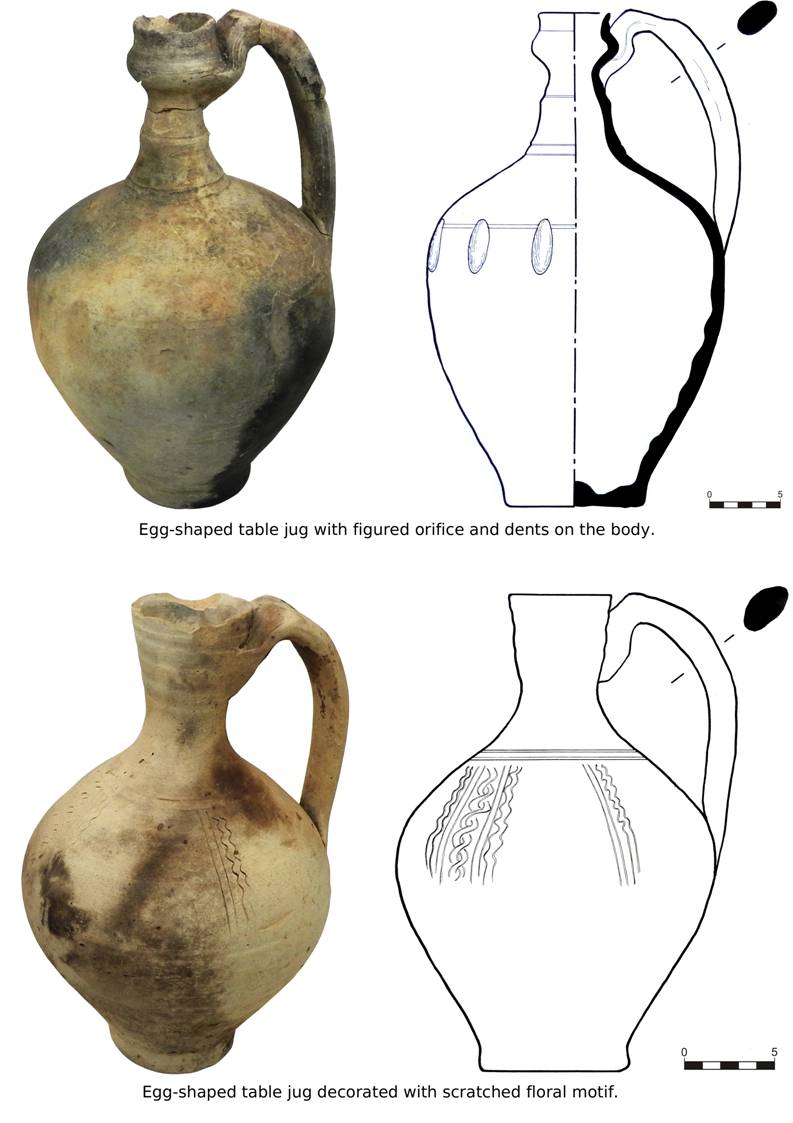

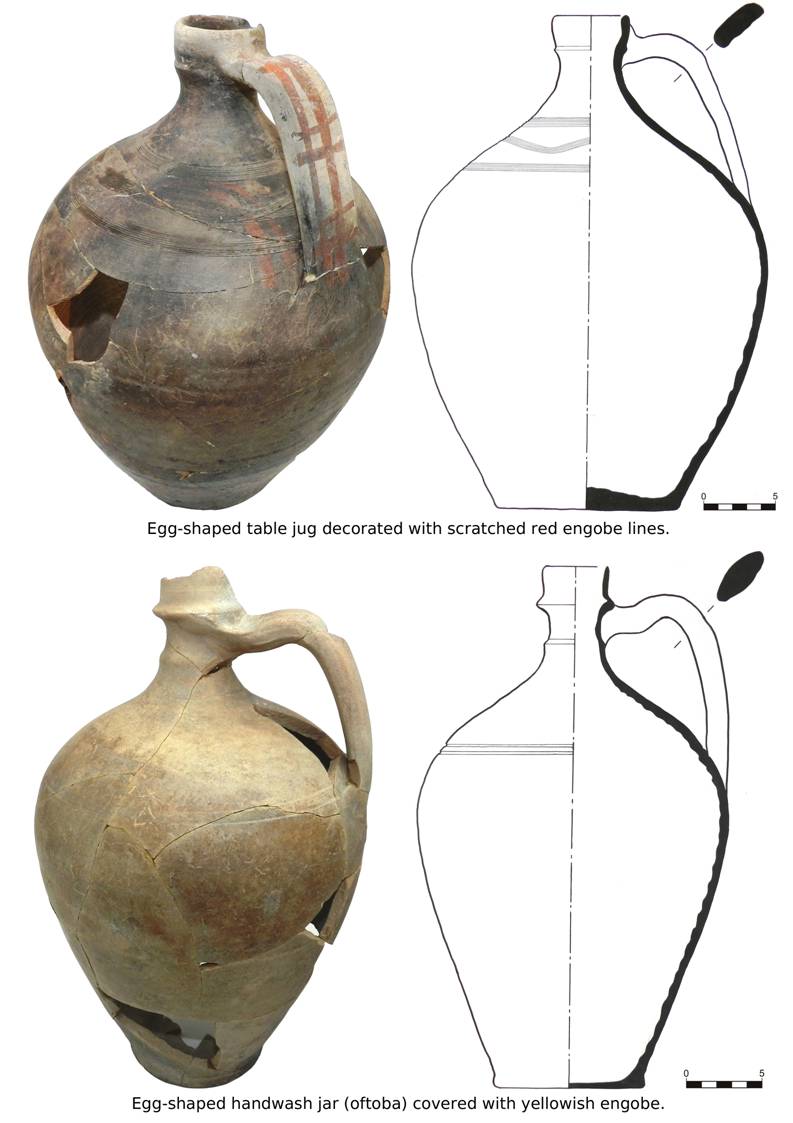

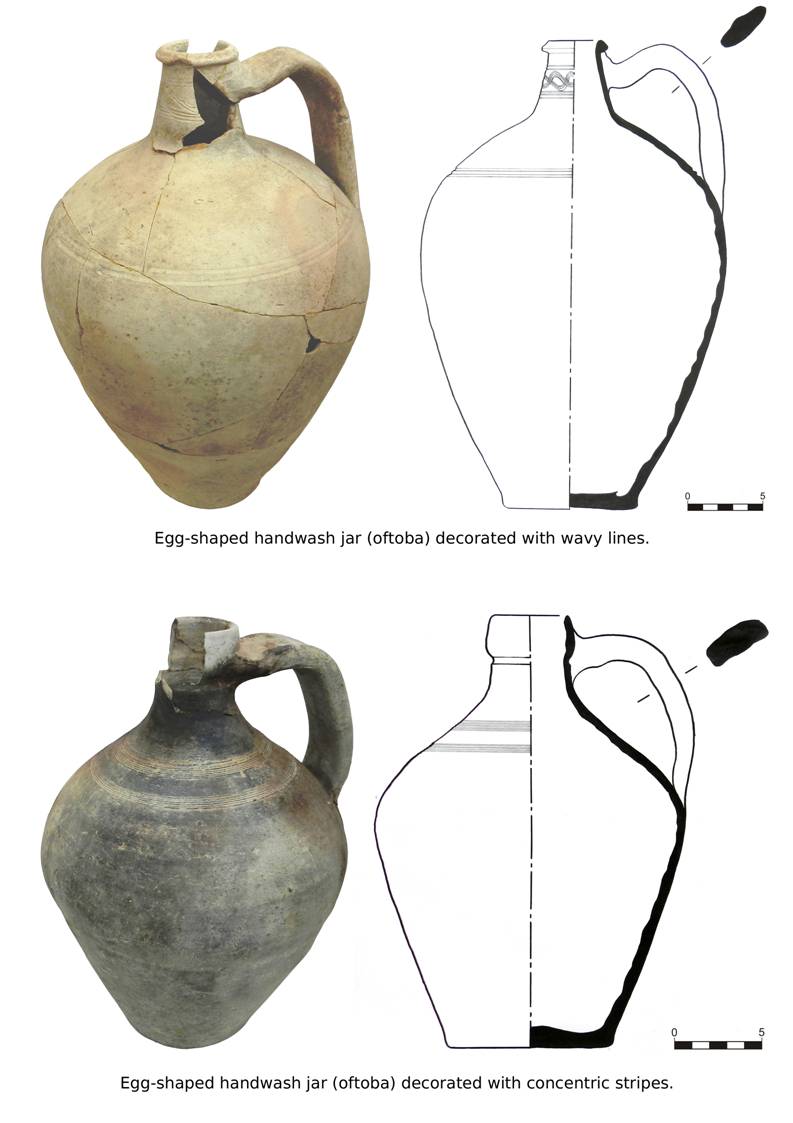

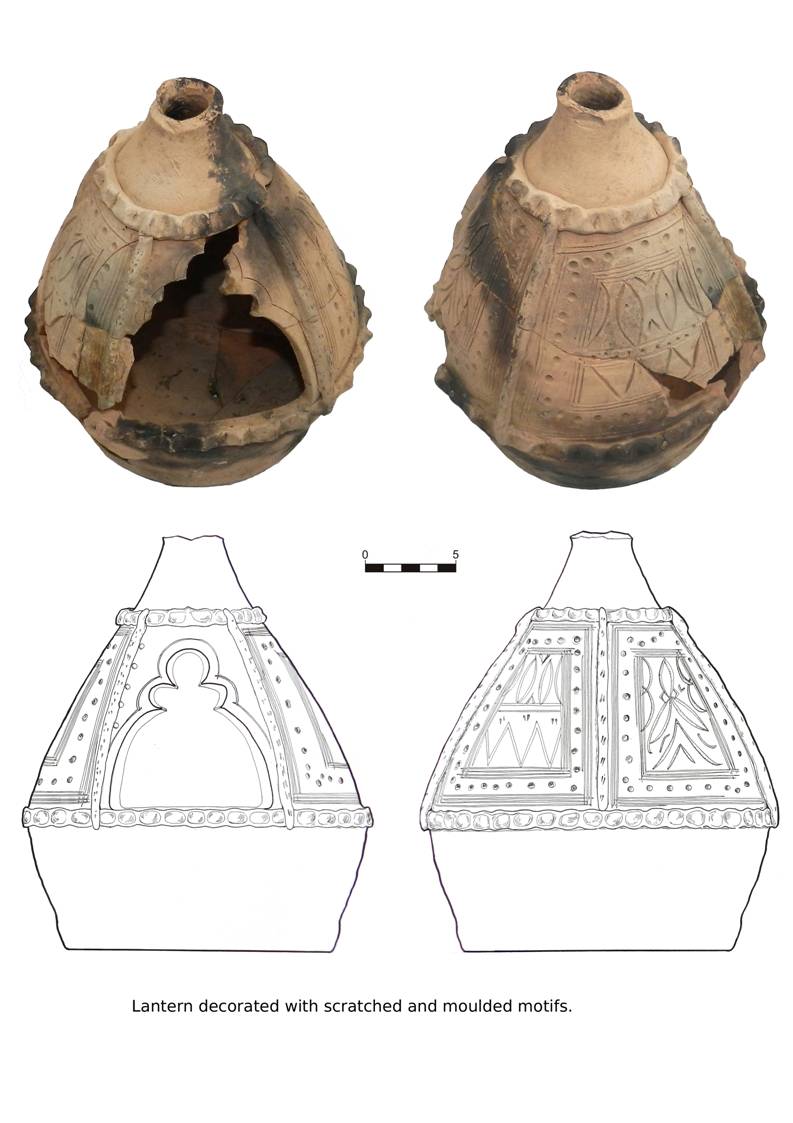

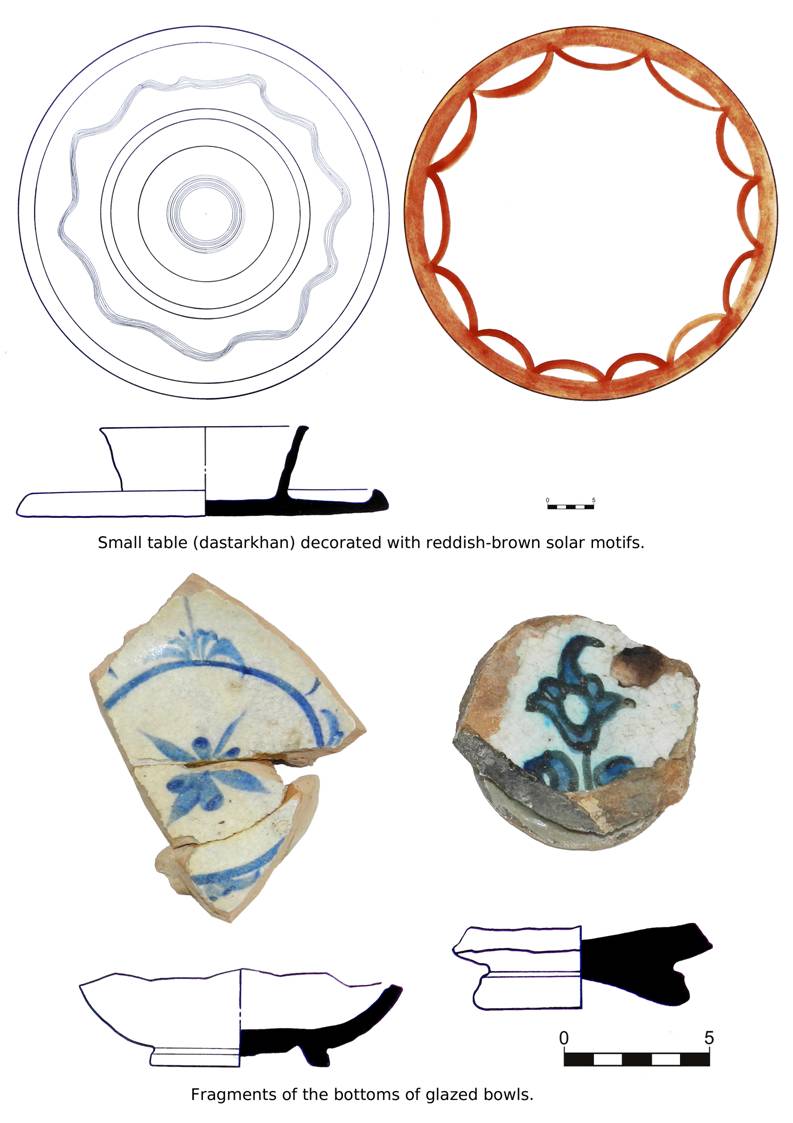

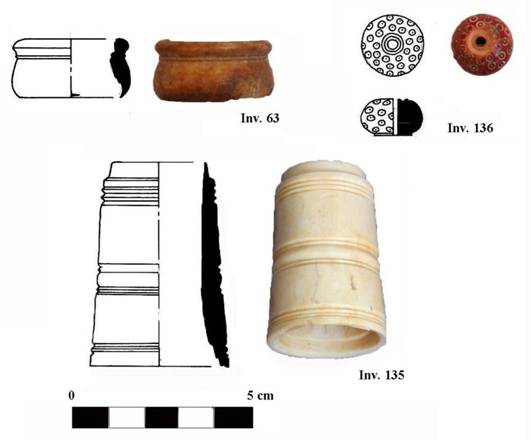

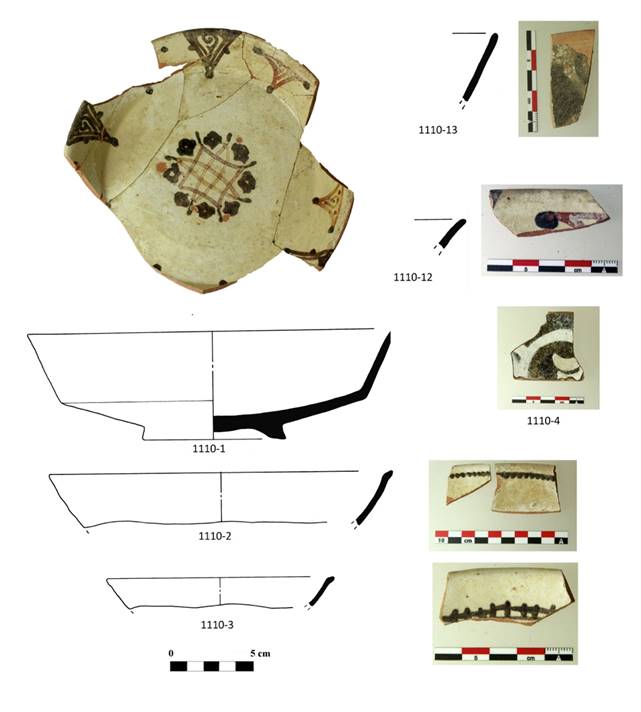

A varied ceramic

assemblage dating to the 12th century –beginning of the 13th century AD was discovered in the large pit hole SU 23 during the 2011 campaign,

but some vessels were reconstructed and then catalogued only this year. The

assemblage contained mostly egg-shaped juglets with funnel-like rim, but there

is also an ovoid jar, two small table pots decorated with thin incisions, a

cooking pot and a lid (Pls. 25-28). All the fragments present traces of

a later fire that interested only the material found in the pit hole (see 2011

report).

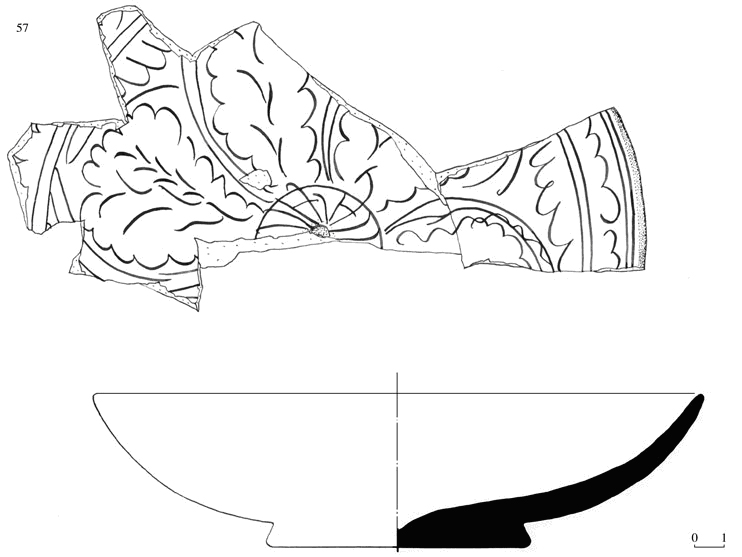

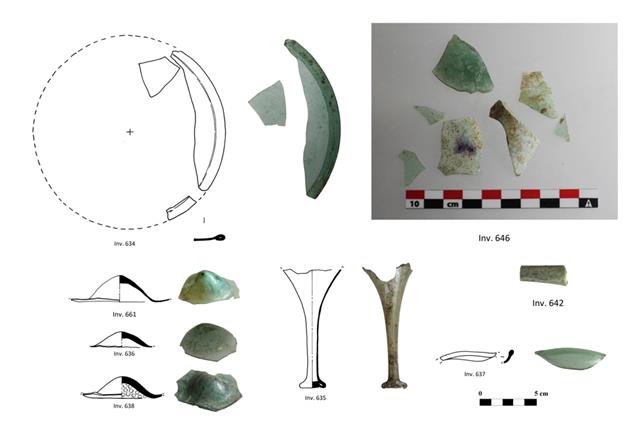

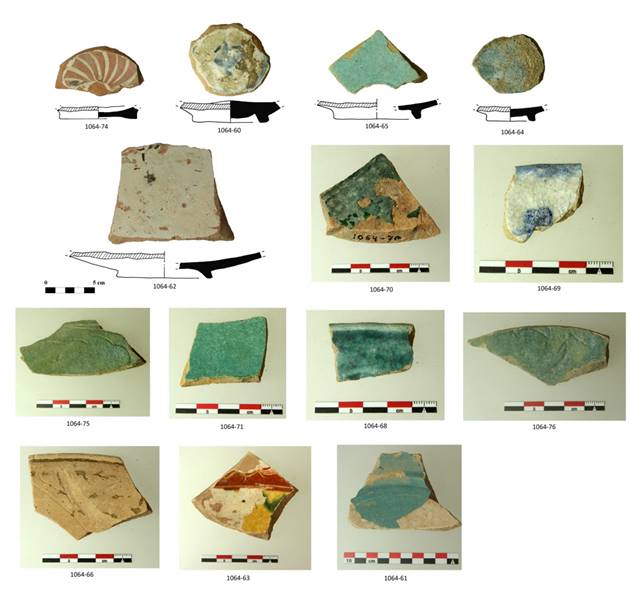

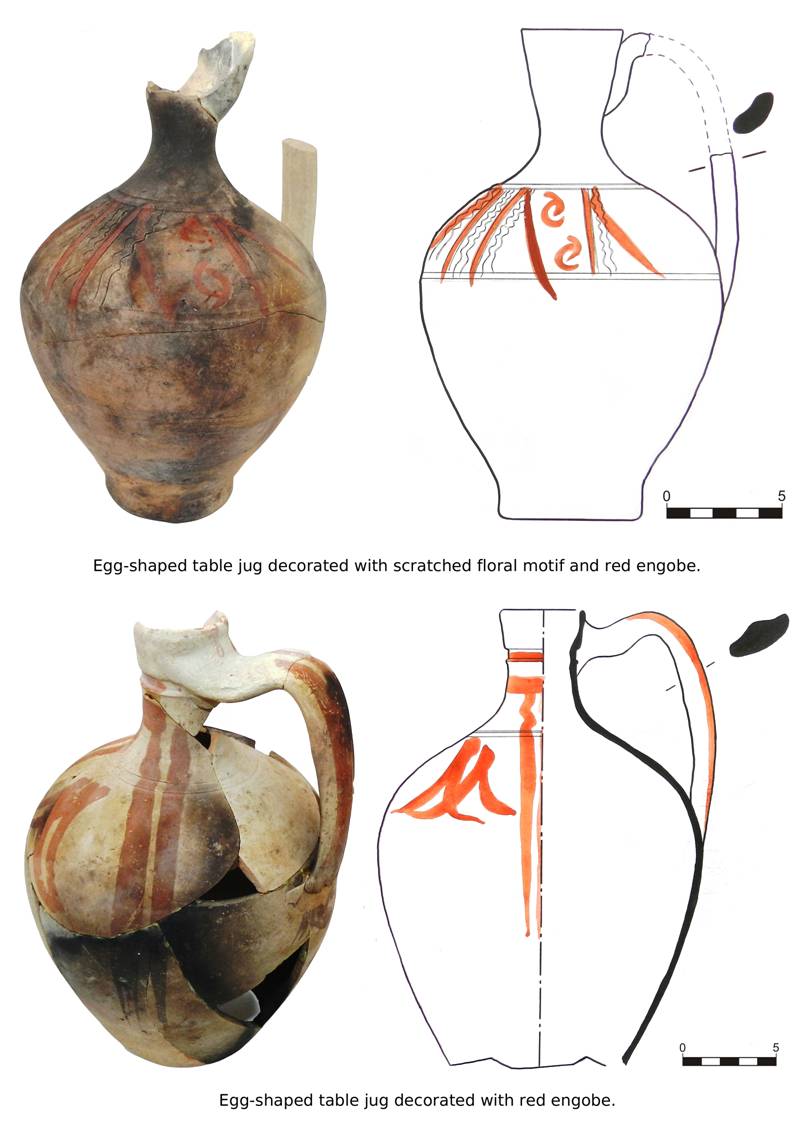

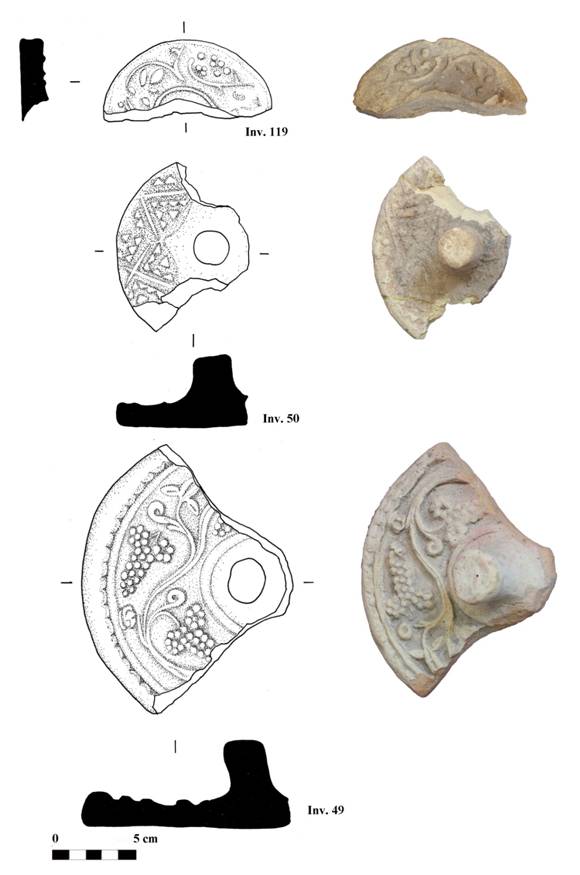

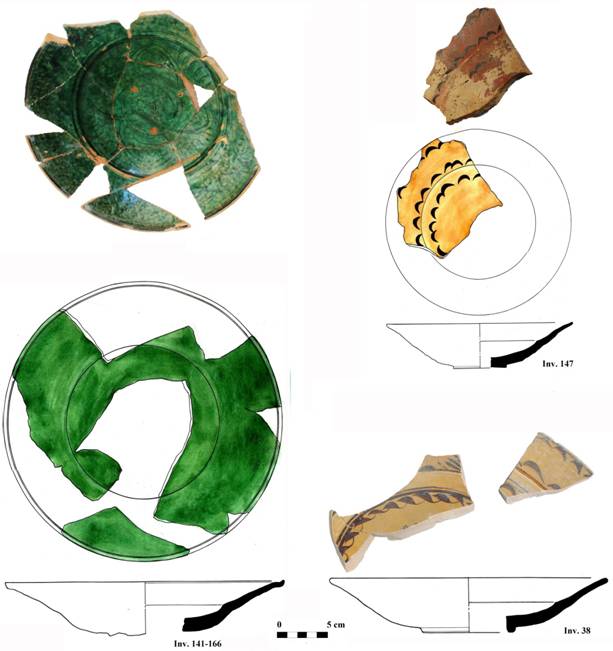

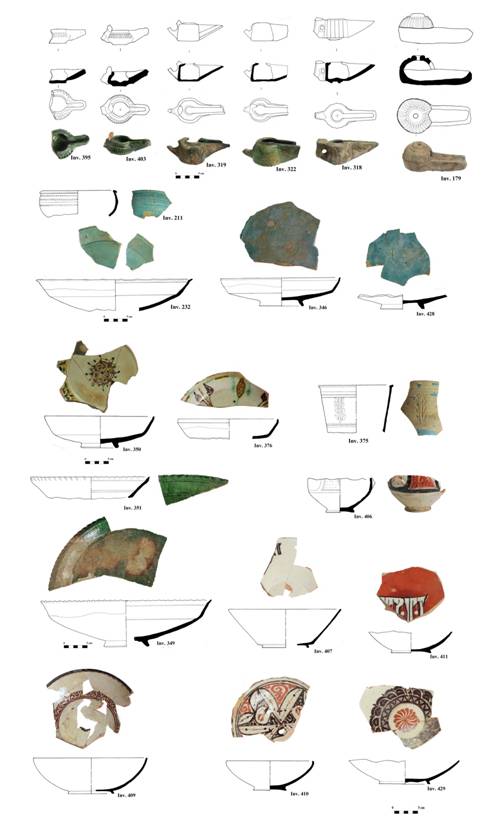

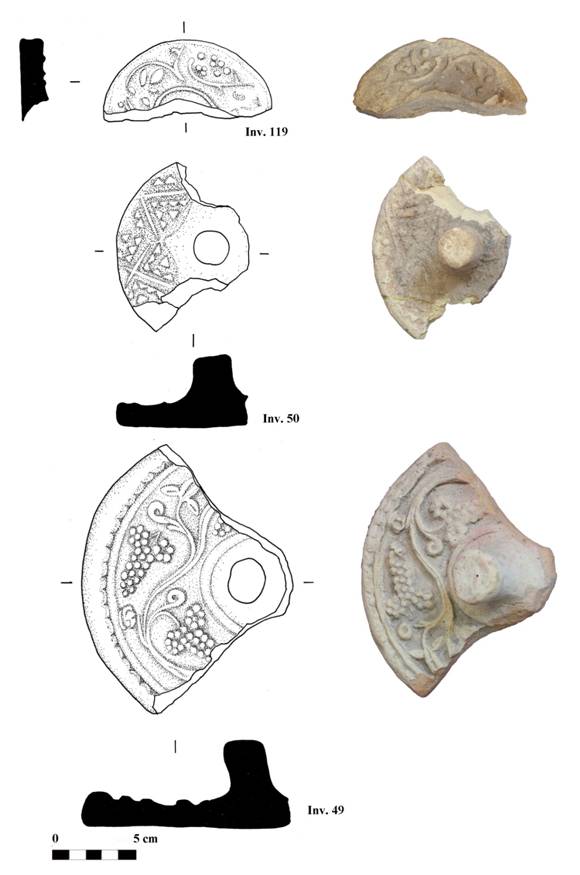

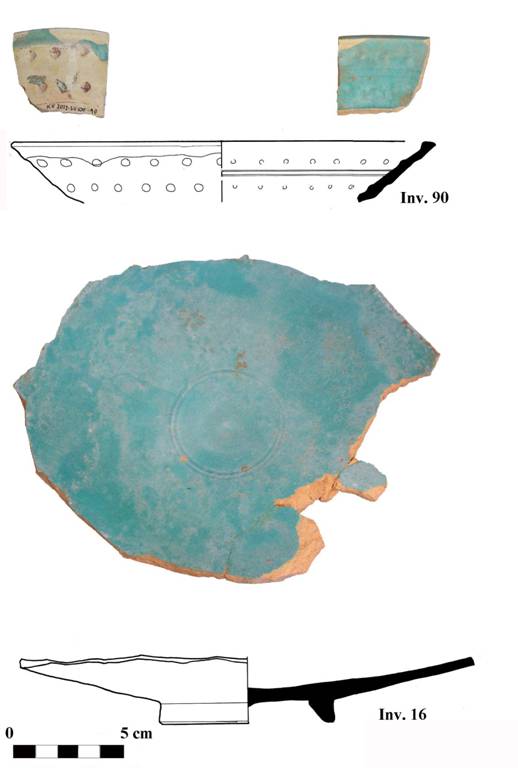

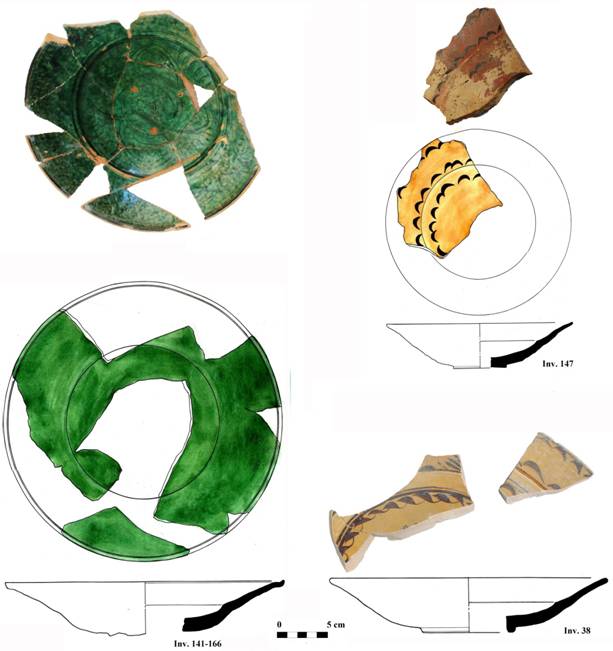

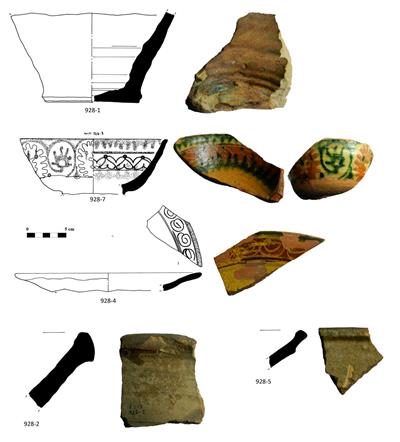

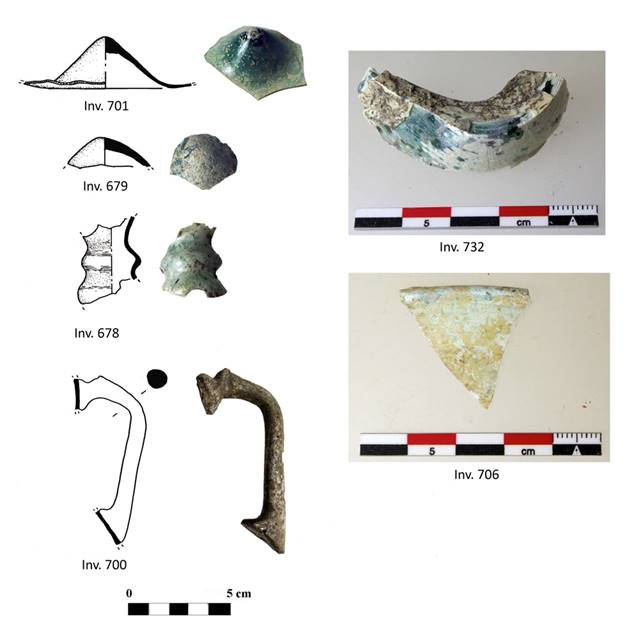

The glazed

pottery dating to the 12th century AD consists of a few fragments of

turquoise plates, a small fragment of a lamp and a fragment of a whitish plate

decorated with radial motif (Pls. 21-24). The pottery dating to the 18th-19th AD centuries includes a glazed greenish plate decorated with scratched stylized

motifs, a yellowish plate decorated with brownish ‘zangir’ motifs, a

glazed turquoise lamp, a small glazed yellowish plate and a pale brownish cup,

decorated with stylized motifs.

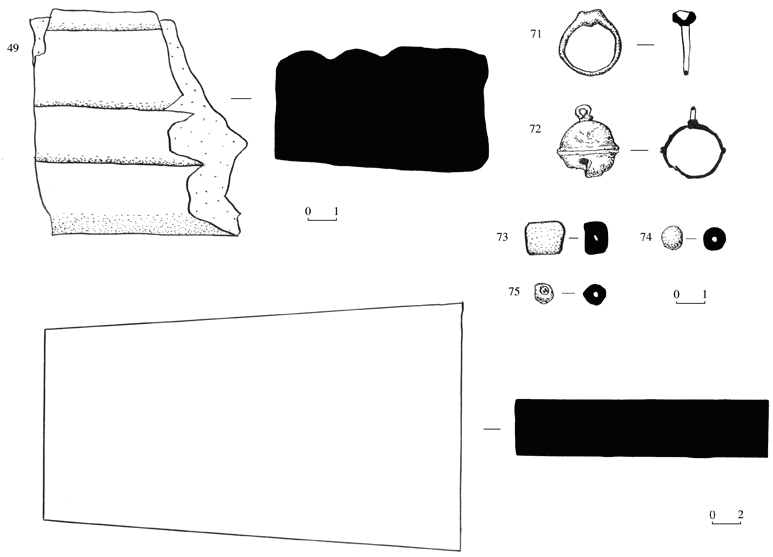

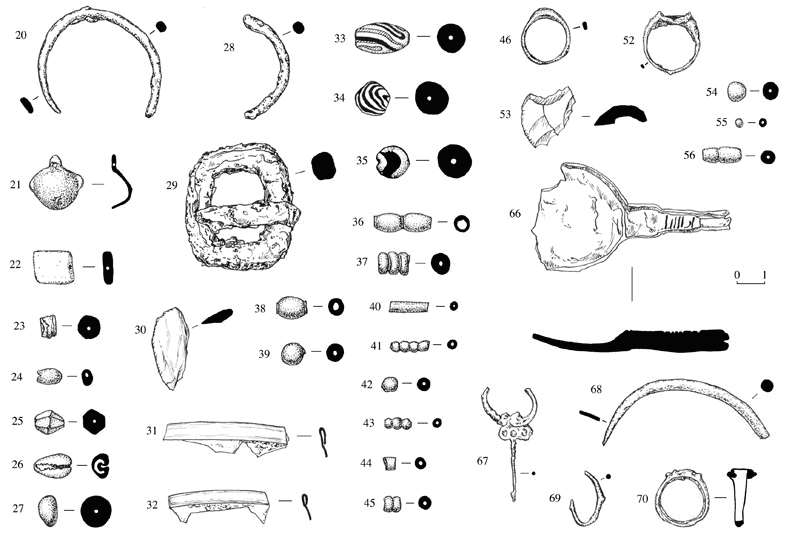

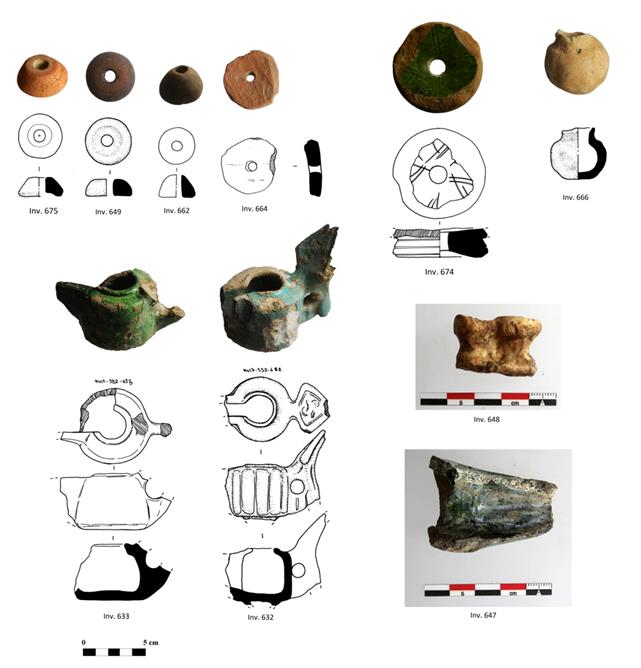

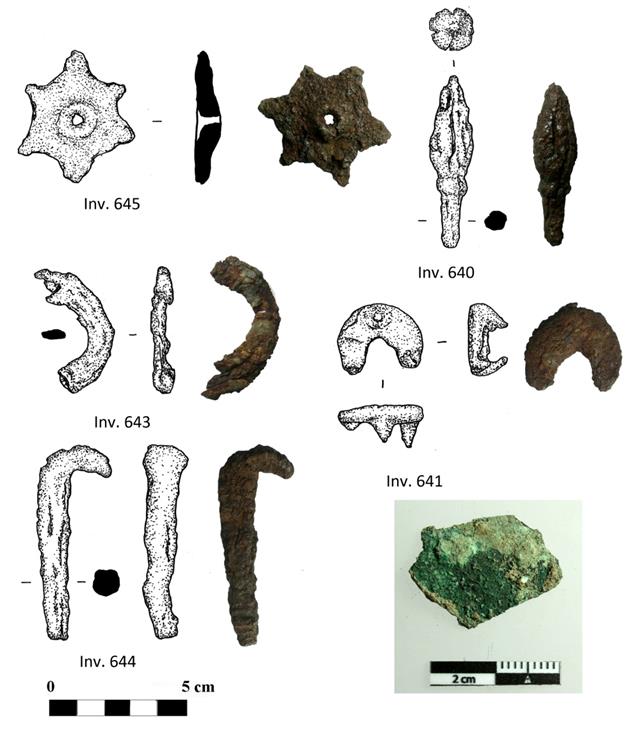

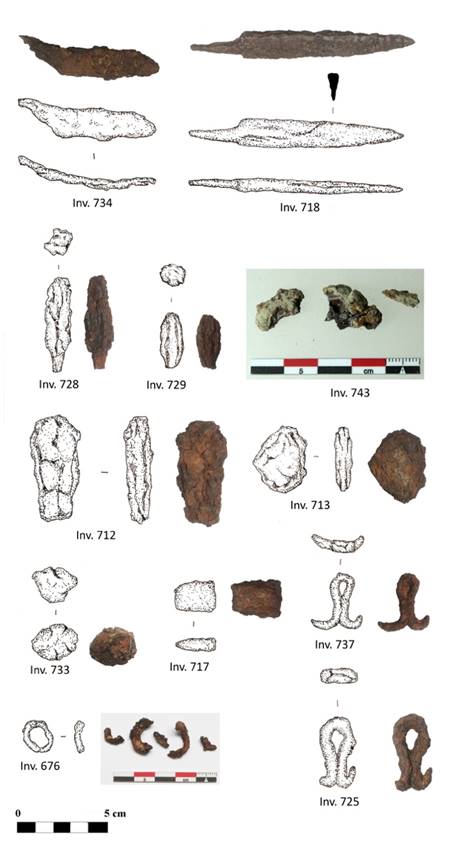

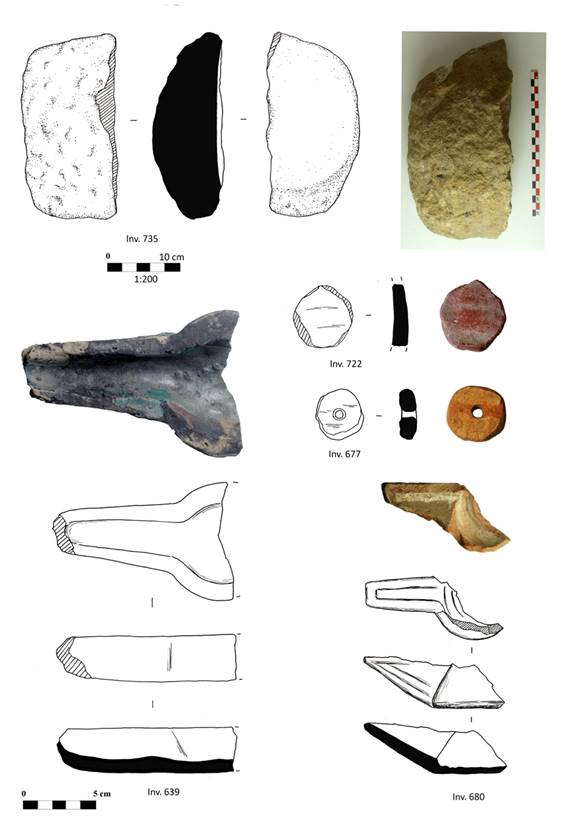

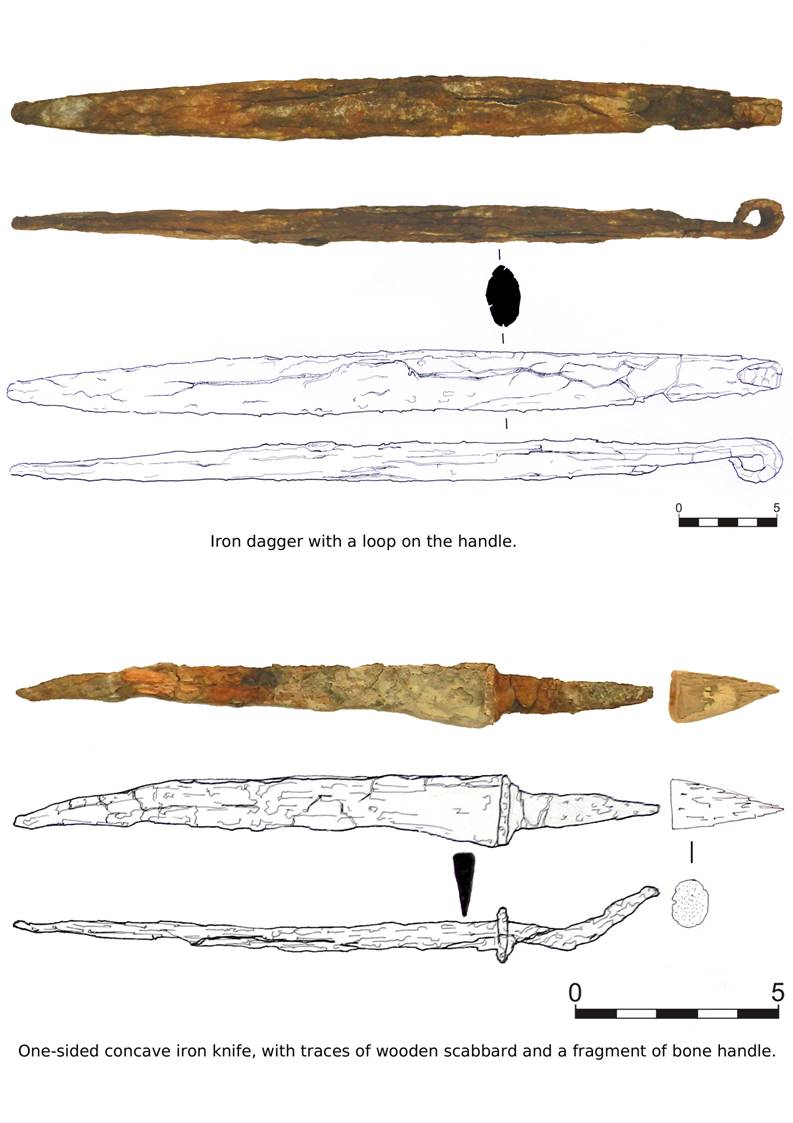

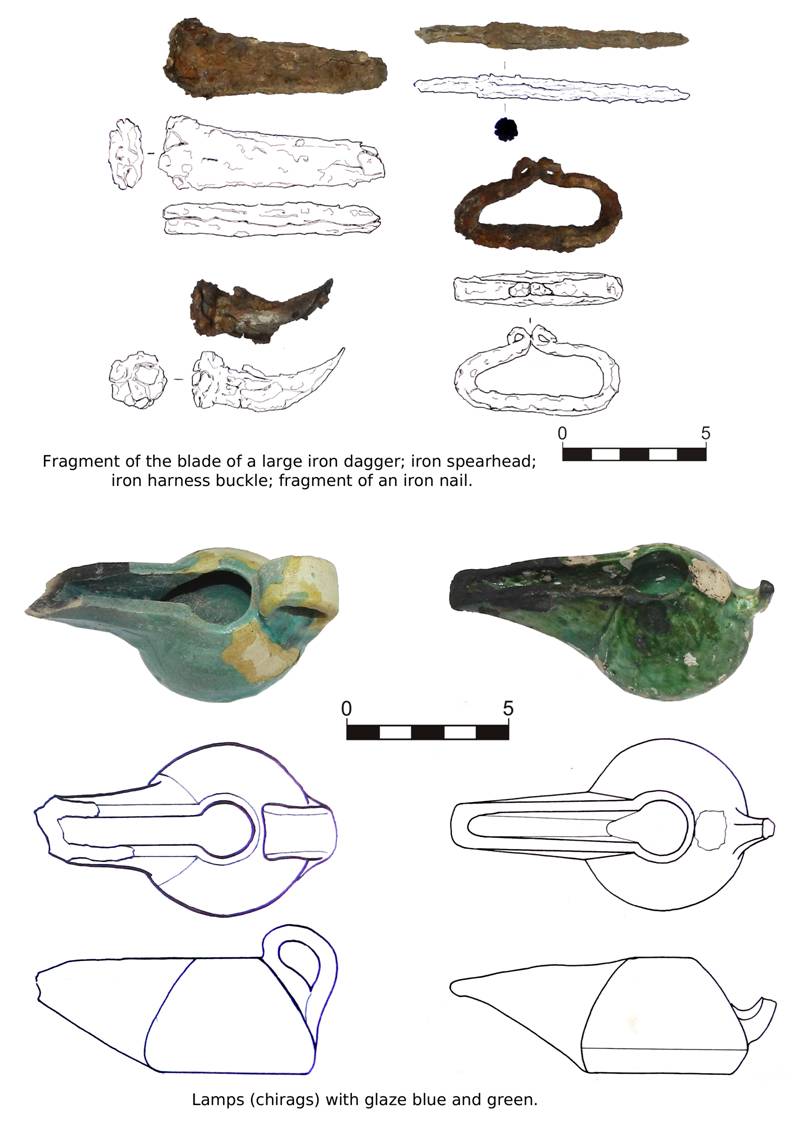

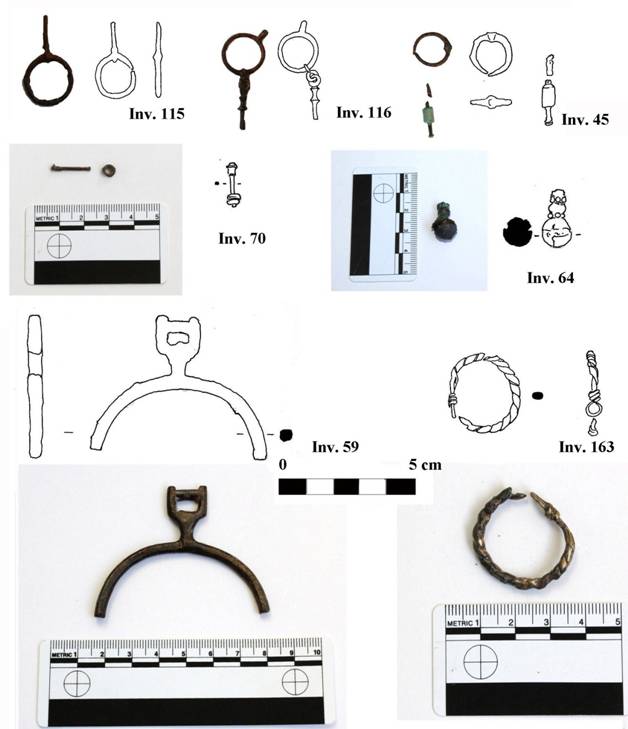

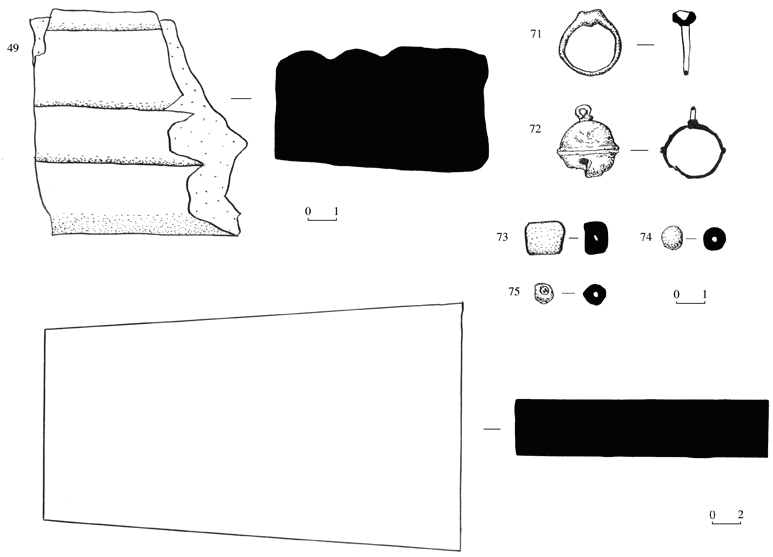

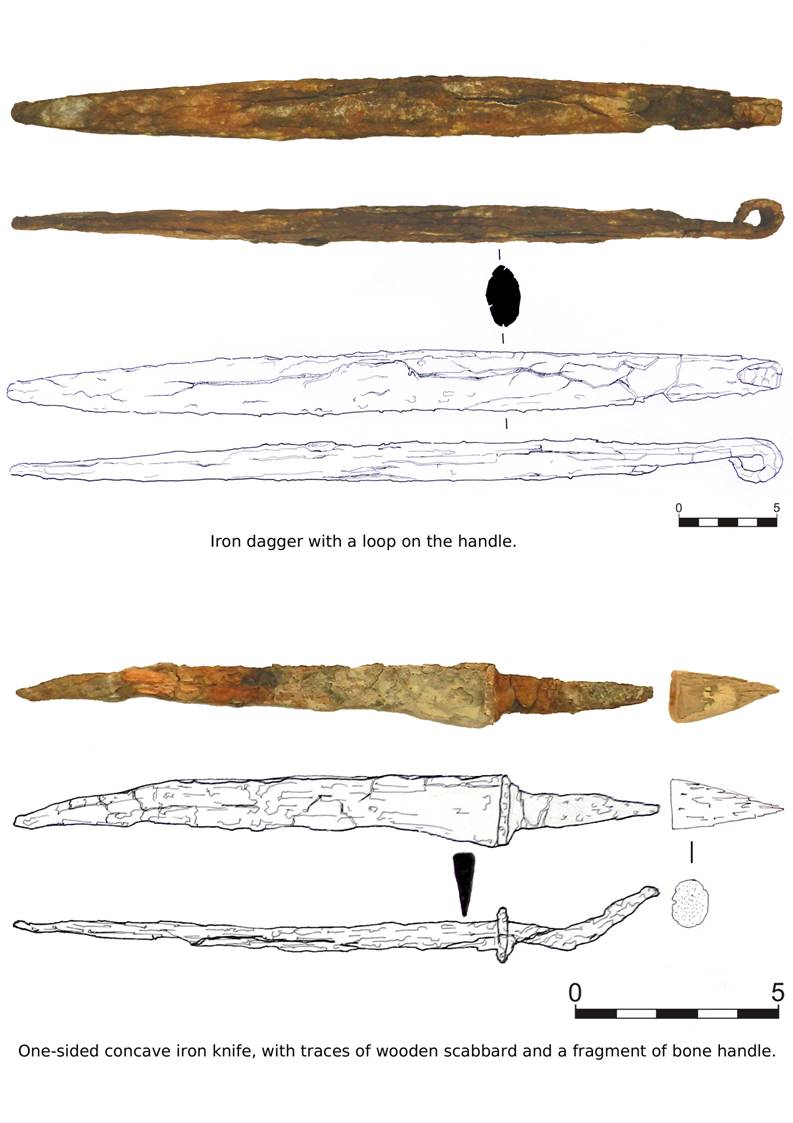

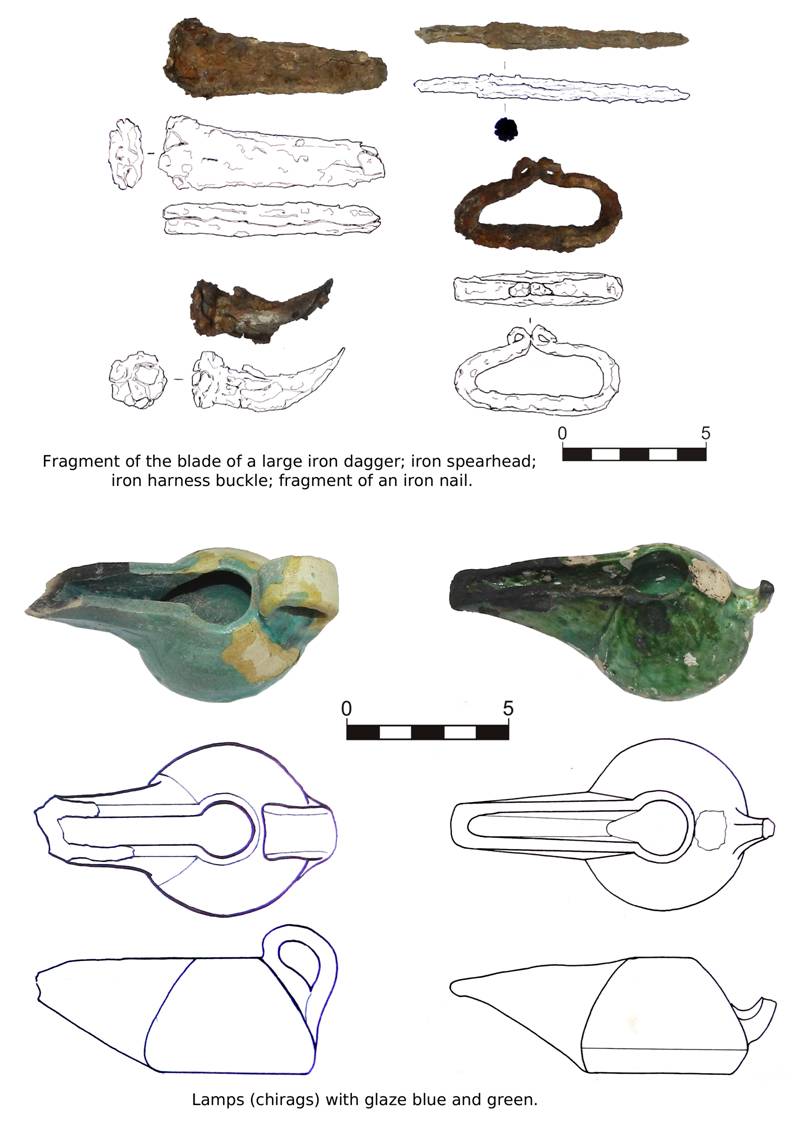

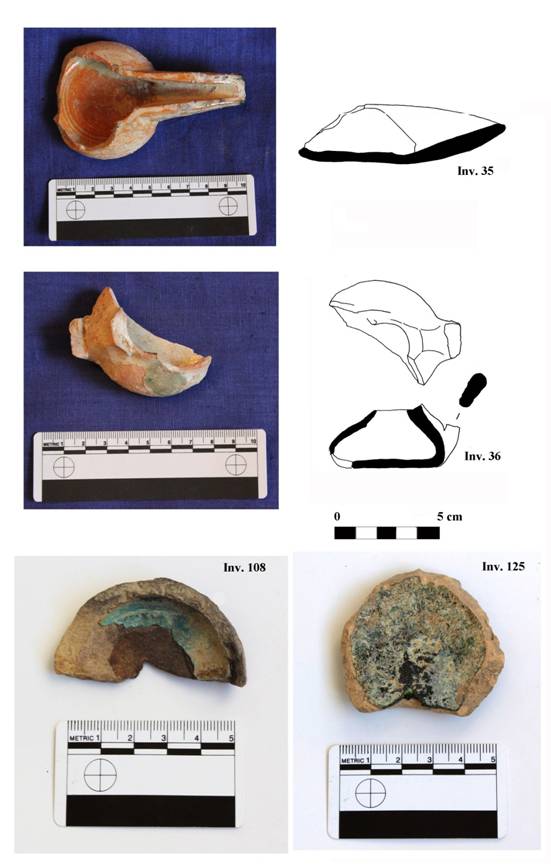

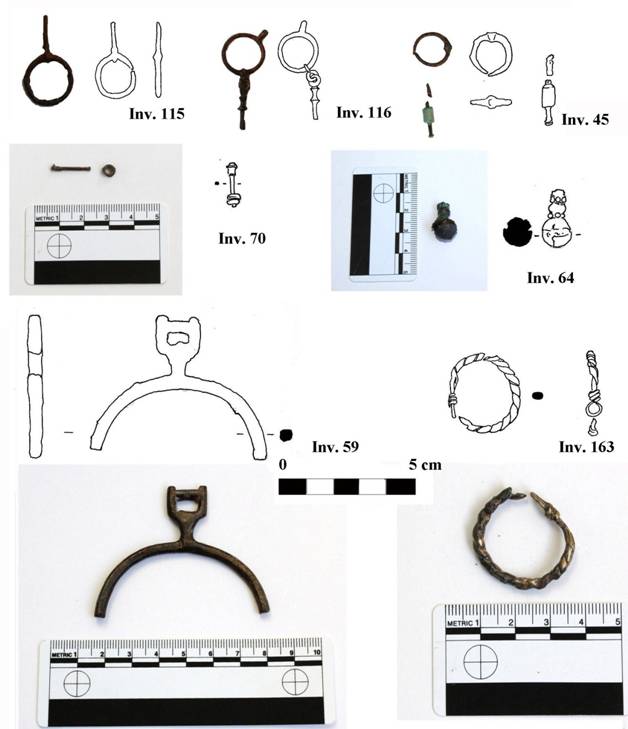

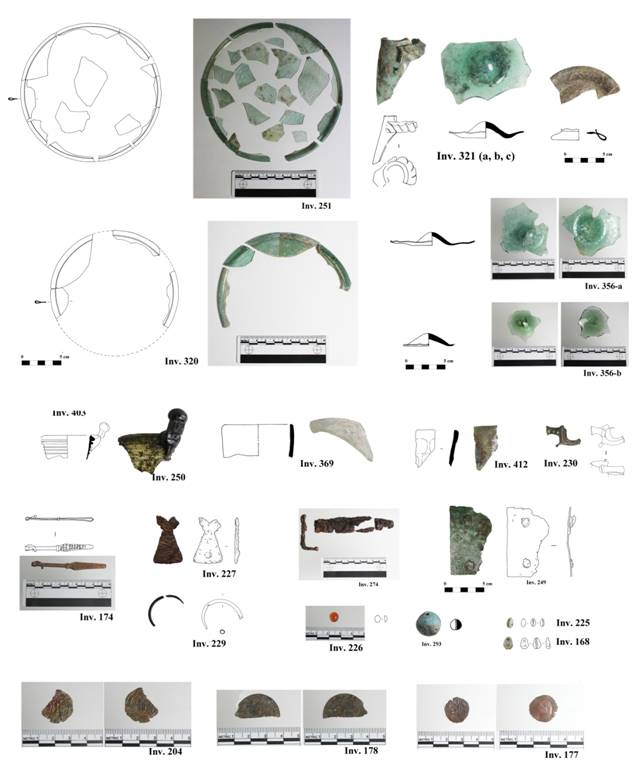

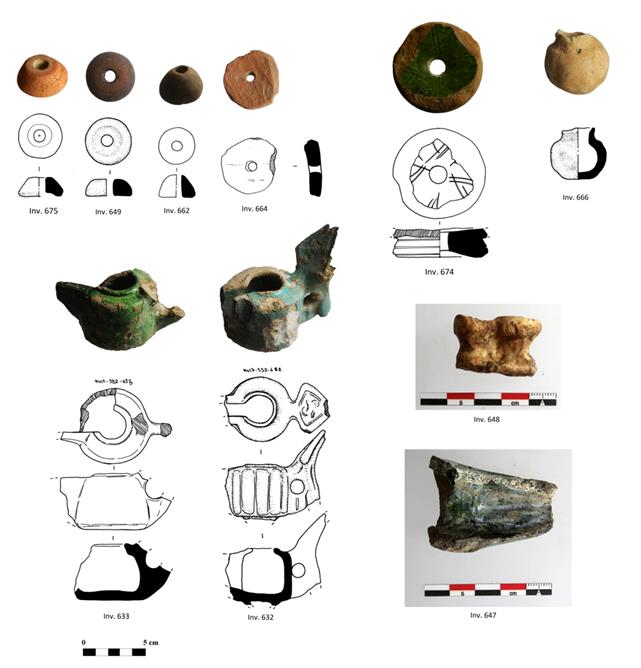

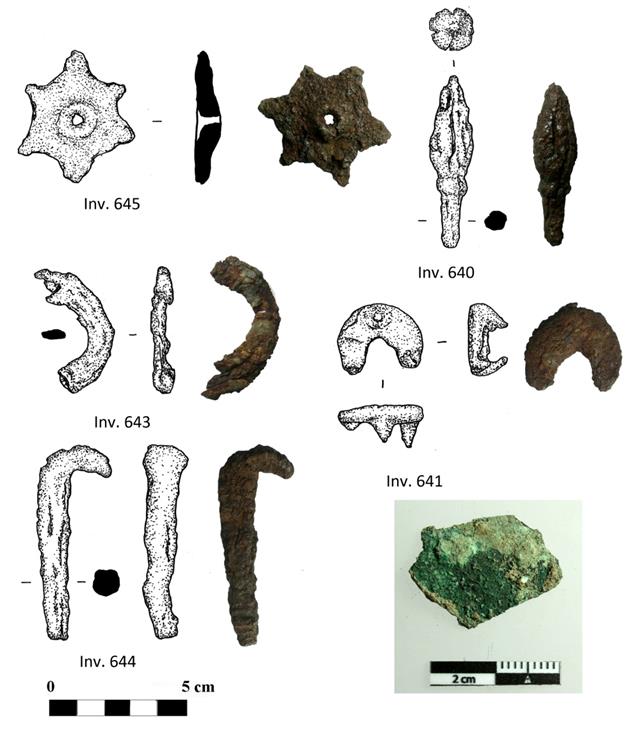

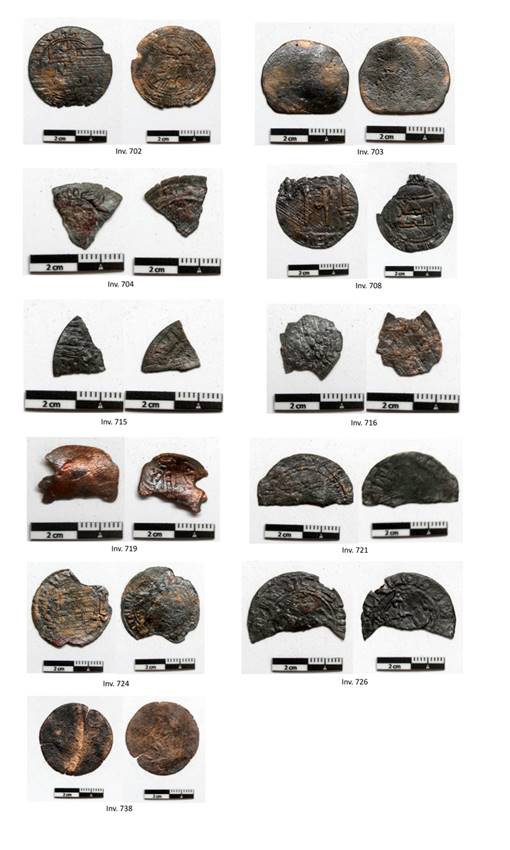

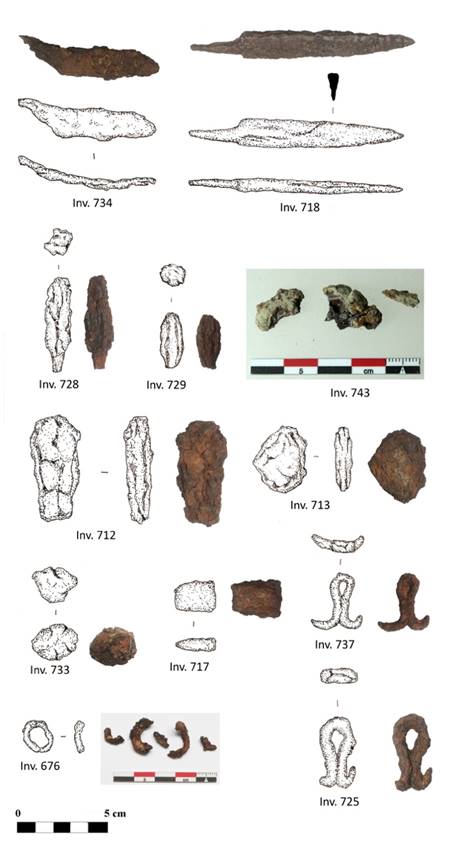

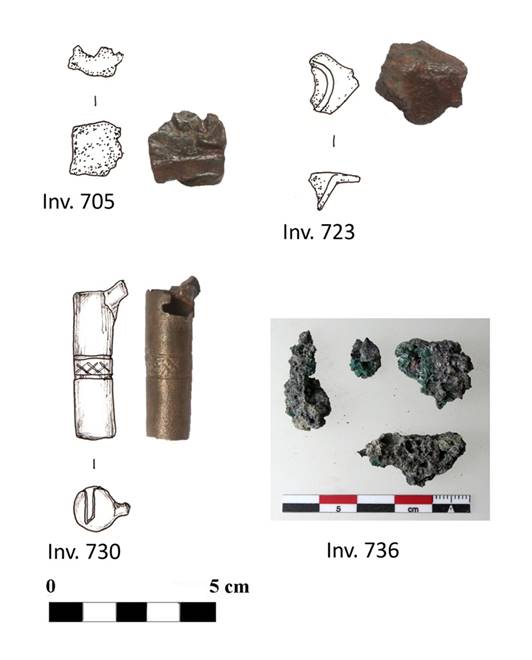

A conspicuous

assemblage of metal artefacts was found this year and it includes iron weapons,

bronze ornaments and a copper coin (Pls. 29-31). Among the weapons are a

sickle of uncertain dating (12th century?) and an arrowhead dated

to the beginning of the 8th century AD. A copper coin pertaining to

the ‘Asbar series’ was discovered in room 7 under the layers formed following

the abandonment of the site and it is of great importance for dating the

structures. Slightly scyphate, on the obverse it is still discernible the

portrait of the king, unusually facing left, while on the reverse it is

represented a stylized fire altar on the Bukharan tamgha. The

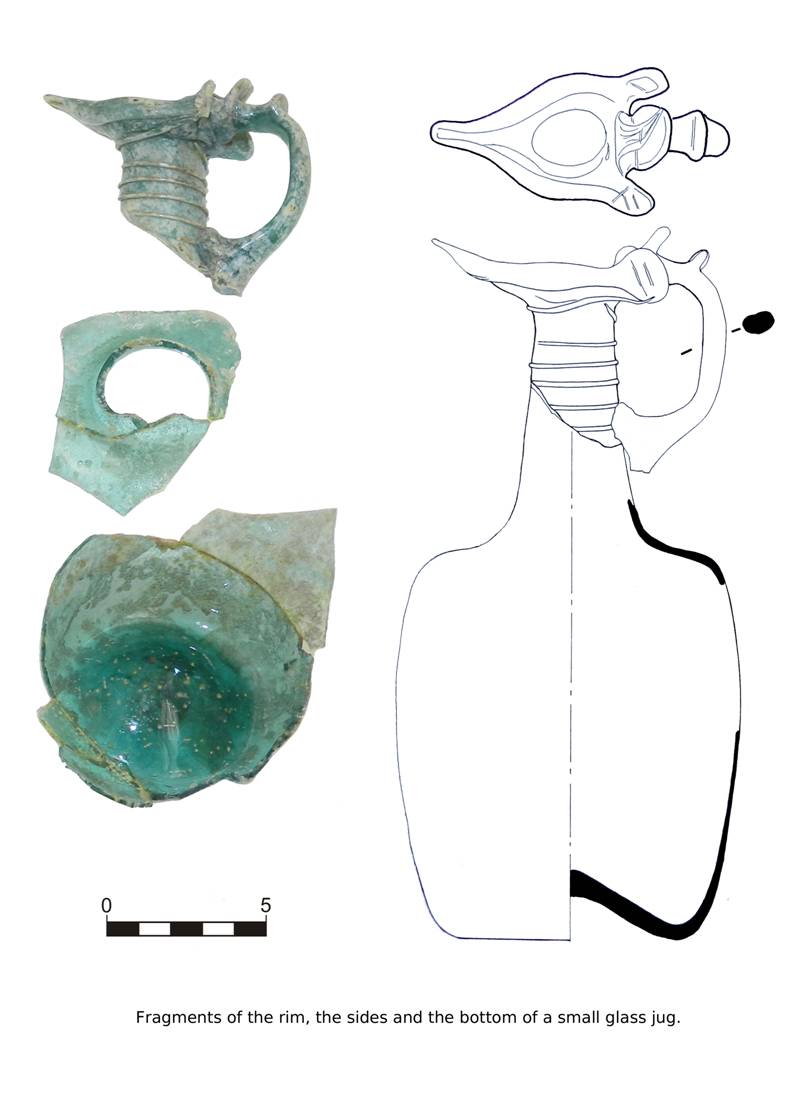

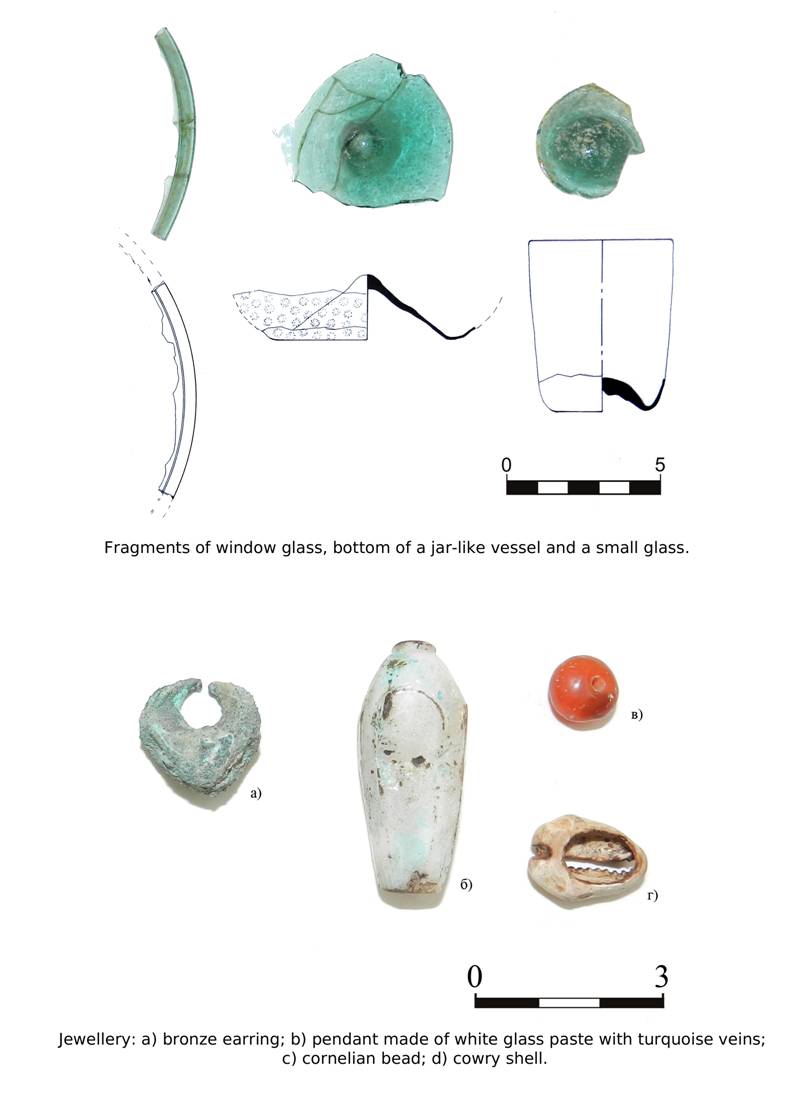

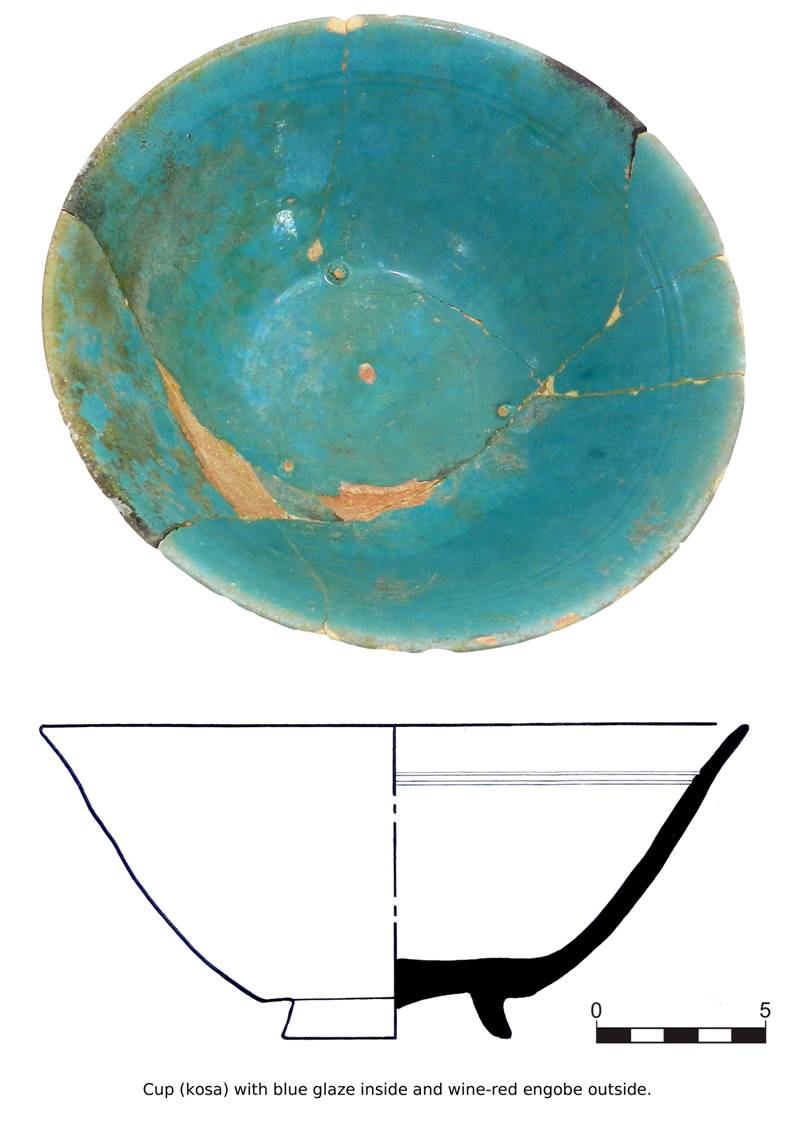

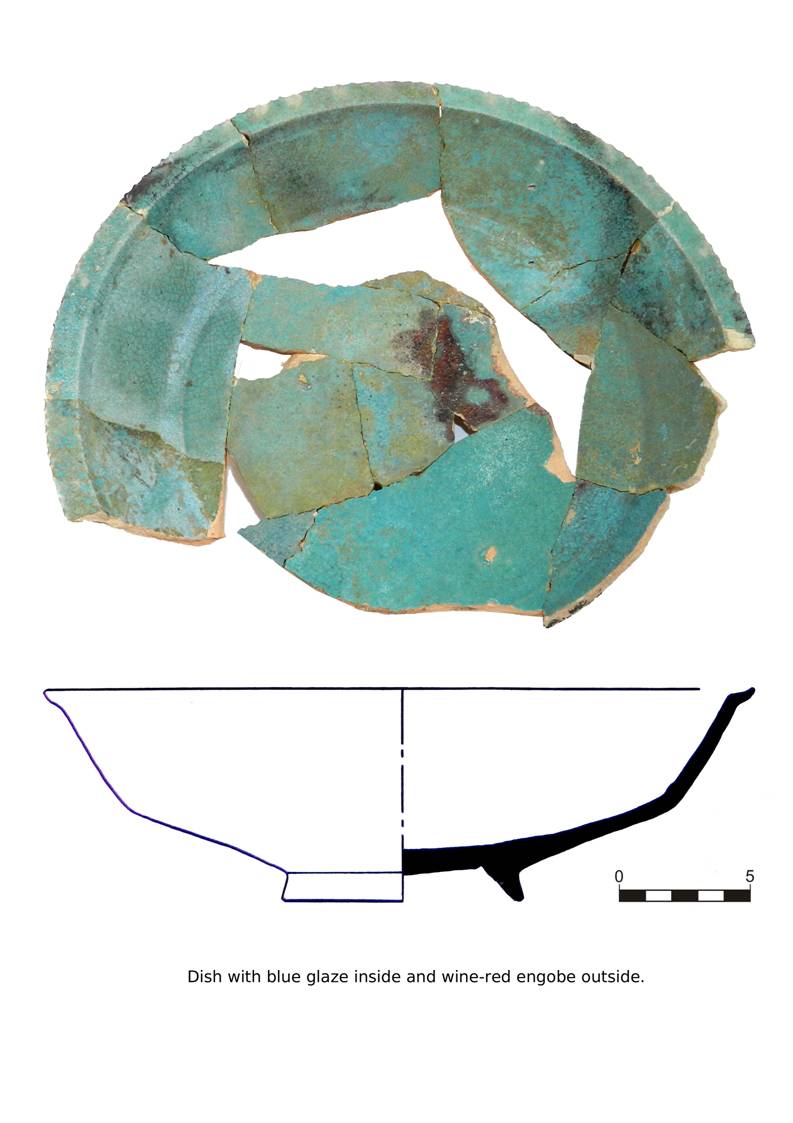

Sogdian legend usually present on these coins identifies the king as Asbar, probably a local Bukharan ruler whose kingdom has