The tenth archaeological excavation on the site of Vardanzeh, the ancient Vardana, was realized between October 7 and November 9, 2019, plus another two days devoted to complete the documentation. The research staff was composed of three archaeologists: Ilaria Vincenzi, Džamal K. Mirzaachmedov and Aysulu Iskanderova. Siroj Mirzaachmedov, architect, updated the topography of the site while Munira Sultanova, architect as well, drew a selection of artefacts, for a total of 385 finds among pottery (311) and small finds (74). The conservator, Dilmurod Kholov, was in charge of the cleaning and the conservation of the artefacts while Anvar Athakodjaev was in charge of the cleaning and the study of the coins found during the excavation.

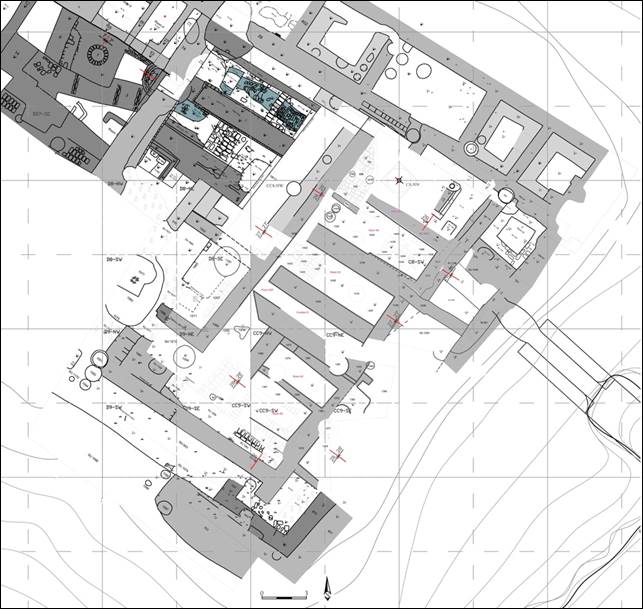

This year the activities focused on the citadel, where we opened only new trenches, all localized in the eastern sector. We can divide the excavated area into two main parts: the first one, under the supervision of I. Vincenzi, was located to the SE of the trigonometric point and included trenches CC8NE, C8NW, CC8SE, C8SW, C8SE, CC8SE, CC9NE, C9SW (in this report referred to as ‘northern trenches’). The second area, excavated under the supervision of A. Iskanderova, was located SW of the previous one and included D8SE, D9NE and parts of D8NE, D8SW, D9NW, D9SE (in this report referred to as ‘southern trenches’). The area investigated this year has a total surface of 152 square metres.

The investigation carried out this year in the ‘northern trenches’ cast some light on two rooms dated to the medieval period (9th-12th cent. AD), one of them is characterized by bath units and underground systems of canalization. The hypothesis is that the bath units were part of a building, possibly a bathhouse, a kind of construction that spread in Mawarannahar from the 9th-10th cent. AD onwards. Some fragments of ‘tiles’, smoothed with paint of red and brown color, have been unearthed; they may have decorated the inner walls of the bathhouse, as we know that the rooms of these buildings were plastered with waterproof paints. Three fragments of decorated baked bricks, possibly part of a doorframe, would also corroborate the presence, on the citadel, of a building of a certain importance, and not of simple dwellings. Among the finds, the circular windowpane fragments, always found in abundance in the medieval deposits, are a further proof of the presence of an important building on top of the citadel. According to the size of the baked bricks that formed the first medieval walls, the origin of the bathhouse could be dated back to the Samanid period, but the building probably experienced a long life, as confirmed by the sequence of floors, by the destruction/abandon of some drainage systems as well as by the type of storage jars and jugs re-used in the canalizations. However, it cannot be excluded that some parts of the bathhouse were no longer in use in the 12th cent. AD, as suggested by the several holes (rubbish pits) that destroyed the medieval walls and that contained pottery already dating to the 12th cent. AD. Another significant result of this campaign concerns the identification of a transitional phase, dated between the 8th and the 9th cent. AD, i.e. from the end of the early medieval palace which occurred after the defeat of Vardan Kudah and the construction of the bathhouse, where this area of the citadel was only sporadically used, possibly by shepherds of passing nomads. On this phase, attested by rammed floors and holes, a mud brick platform was built. The platform covered this abandoned phase and constituted the base of the later medieval structures, such as the bathhouse. As far as the early medieval palace is concerned, the excavation carried out in the ‘southern trenches’ revealed, under the deposits dated to the medieval period, a room (48) that was part of the eastern sector of the palace. This room, located to the south of the large hall 32, had a square plan and probably a sufa on the eastern side. Also here, as already attested in hall 32 unearthed northwards, traces of mural paintings were found in the infill of the room, confirming that this area was probably used for representative purposes. In the ‘northern trenches’ we only detected some walls that belonged to the early medieval palace, on which the medieval structures were built.

Pottery

A total of 5.848 pottery fragments were unearthed this year, among them 5.003 un-diagnostic (87%) and 739 (13%) diagnostic potsherds: the majority is represented by un-glazed ware (97%) and only 3% consisted of glazed ware. As already explained above, this year we found a lot of pottery in rubbish pit SU 1191: all the fragments were counted, but not all of them were registered in the Database, since the glue process is still going on. The potsherd from this pit represents the 46 % of the whole pottery unearthed this year. The analysis of the functional classes within the diagnostic pottery unearthed this year evidenced, as usual, that the most common class is represented by storage ware (66%), followed by glazed table ware (15%) and by cooking ware (10%). The un-glazed tableware represents the 3%, the storage ware re-used as pipelines the 2% while the specific pipelines the 2%. A small percentage (2%) consisted of glazed oil lamps (1%), and of pottery used for specific purposes (stamp for pottery, weight loom, trays).

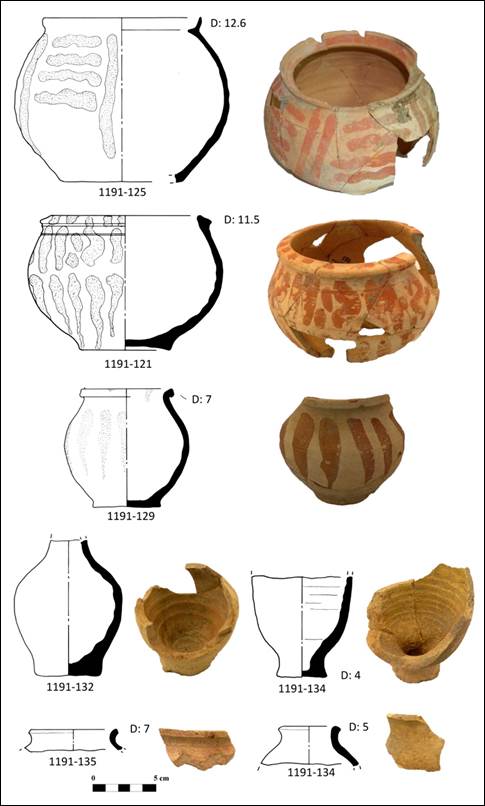

Only few potsherds represent the early medieval pottery. Specimens dated to the 5th-6th cent. AD consist in fragments of large storage jars (khum) decorated with circular finger marks impressions, as well as a rim of jug characterized by an S-shaped profile. A fragment of cooking ware dated to the 5th cent. AD was also found. Pottery dated to the 7th-8th cent. AD is also meagre in number and it is mainly represented by several large jars decorated with elongated finger marks impressions and red stripes of paint. Besides the storage jars, a rim of an oinochoe-like juglet, made of depurated clay, can probably be dated to the same period, as well as the handle of a jug made of less refined clay that shows a rectangular section with slightly marked extremities.

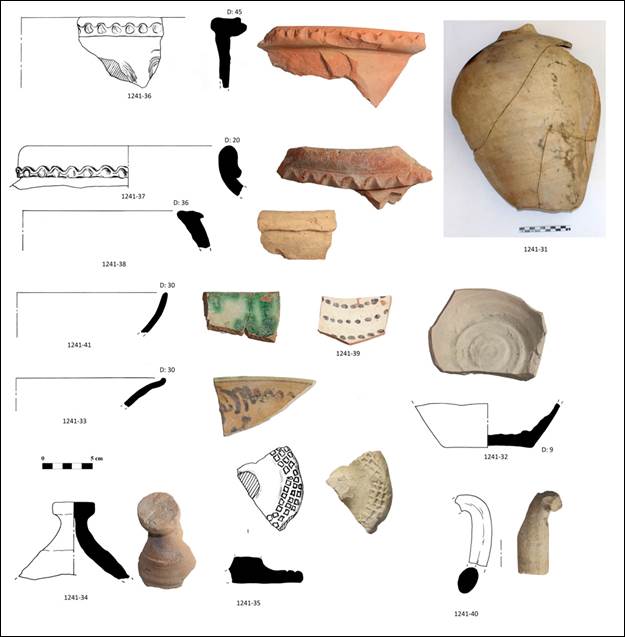

The majority of pottery unearthed this year is represented by Medieval finds and can be divided, according to the forms and the decoration, into the following chronological periods: 9th-12th-early 13th, 16th-18th centuries AD. The pottery dating to the 9th cent. AD includes two fragments of hemispherical dishes covered with white opaque alkaline glaze with spots and streaks of turquoise paint. Among the materials dated to the 10th cent. AD, we have three fragments of the rims and walls from dishes and bowls. The first fragment is covered with white engobe and a green-yellow-brown motif on a white background. The second is characterized by white engobe coating and epigraphic ornament, while the third is painted with black, red and olive flowers on a white engobe background. Among the finds from the south-eastern excavation are two fragments of bases. In the first case, a stylized floral motif of brown and green paint is applied on the white background. In the second, a stylized vegetal scratched motif, coated with greenish glaze, is applied on a white background. Pottery dating to the 11th cent. AD is represented, in the northeastern excavation, by fragments of a rim, walls, and the bases of dishes and bowls characterized by white ornamentation of the background and a dark brown rosette, as well as floral, geometric and pseudo-epigraphic ornamentation. Pottery dating to the 12th / beginning of the 13th cent. AD is represented by fragments of rims of dishes and bowls, by bases of jugs and by the body of a lamp (chirag) covered with turquoise glaze and, in the last sample, green glaze. Among the pottery from the south-eastern excavation some tableware (more than 30 archaeologically intact pieces and fragments - the pit complex has not yet been fully processed) have been identified. They consist of bowls, dishes, cups, lamps completely covered with opaque turquoise glaze. In the sector of pottery from the north-eastern and the southern trenches, more than a thousand fragments of unglazed ceramics of the second half of the 12th – beginning of the 13th cent. AD were found. More specifically, in the southern trenches we found large quantities of fragments of ceramic cauldrons, basins (tagora), lids of jugs and jars, lids, pipelines, mercury bowls (sim-ob), jugs used as tableware and jugs used as storage ware, pots, portable lanterns (fanus) and jars (khum). This material, whose complete study will require another 5 months of scientific processing, represents a large and closed complex dating to the pre-Mongol period, and it represents an important occasion to shape the integral characterization of the ceramic production of this period. Among the potsherds dating from the 16th -17th cent. AD, unearthed in the south-eastern excavation, a potsherd of a dish (1198-232) and the base of a bowl (1180-117) were identified. They represent typical examples of glazed ware dating from this period. The first specimen (1198-232), covered with bluish glaze, shows a dark brown floral ornament applied against a white background. On the second (1180-117), two ribbon lines and a spiral curl are drawn with dark brown paint over the white background of the engobe.Pottery dating to the 18th cent. AD is represented by a large number of fragments of glazed bowls and dishes, with a predominance of the latter. These are bases, walls and rims, covered with a thin mono-color glaze, ranging from yellow to green, without engobe. The items characterized by a yellow background are ornamented with simple floral motifs, stylized, of dark brown color. The dishes are covered with dark green glaze, often without ornamentation or characterized only by schematic vegetal motifs engraved on the surface. Several specimens have no decorative motifs or glazing. In some cases, potsherds can also be covered only with a reddish-brown engobe.

Finds

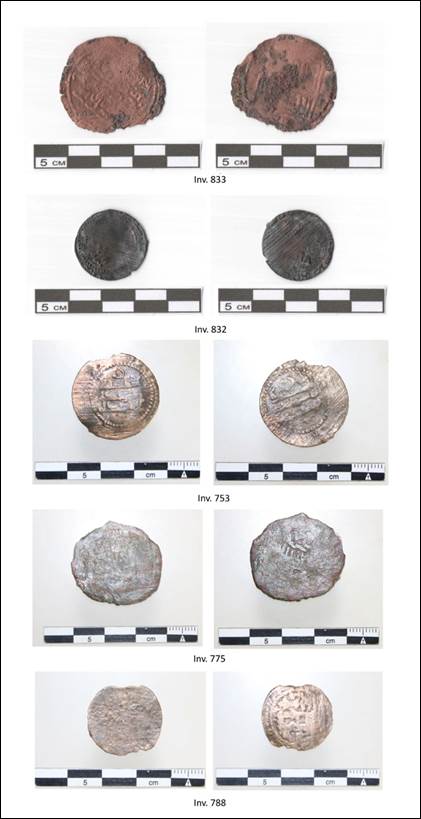

The corpus of the finds unearthed during the archaeological excavation of this year is quite large, it includes metal objects, glass objects, stone finds, terracotta finds, faience (kashin) finds, bones objects and a fragment of cotton fabric. The total number of the inventoried finds is 89. The metal artefacts are 27 in total: 21 iron objects, 5 coins and 1 copper mirror. With regard to the coins (Fig. 117,) we have to underline that two coins were found in the filling layer, the other three in the large hole SU119. All the coins were oxidized and, after been cleaned, a copper coin resulted to be a fake, produced around the end of 10th early-11th cent. AD and circulated during the same period. Two copper coins are Qarakhanid of Ilek Yusuf b.’Ali dated 1st half of 11th cent. AD. Another specimen, dated 13th cent., is a silver washed copper dirham of Khwarizmshahs Anushteginid Muhammad b.Tekishof Seljuk dynasty [1] . The last one is a billon coin, almost illegible, found in the filling layer SU1255, next to the trigonometric point. This specimen is dated to the second half of the 17th - beginning of the 18th cent. AD.

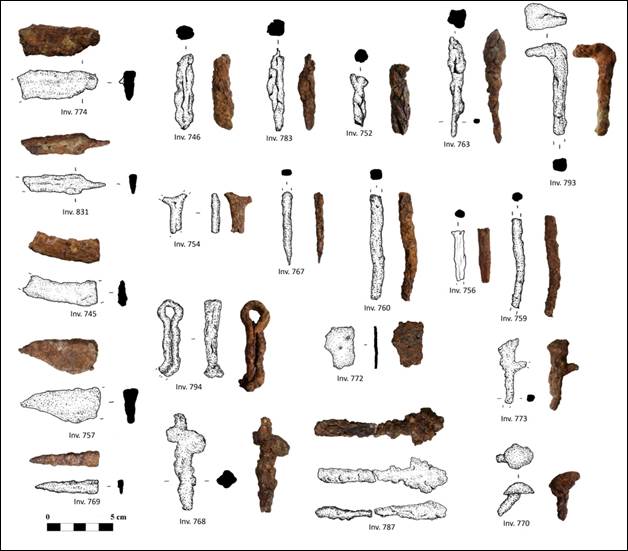

The assemblage of the iron finds, all dating from between the 10th and the 12th cent. AD includes: fragments of knife blades; fragments of nails; an arrow blade; two dagger blades; part of a coating; two fragmented parts of a door locker; a hook-shaped object, also part of a door locker, plus six objects of unknown use. A little fragment of an iron object has been interpreted as a part of the ring-shaped handle of a cosmetic pot. A circular and flat copper object, fragmented and covered by rust, was also found and interpreted as a mirror.

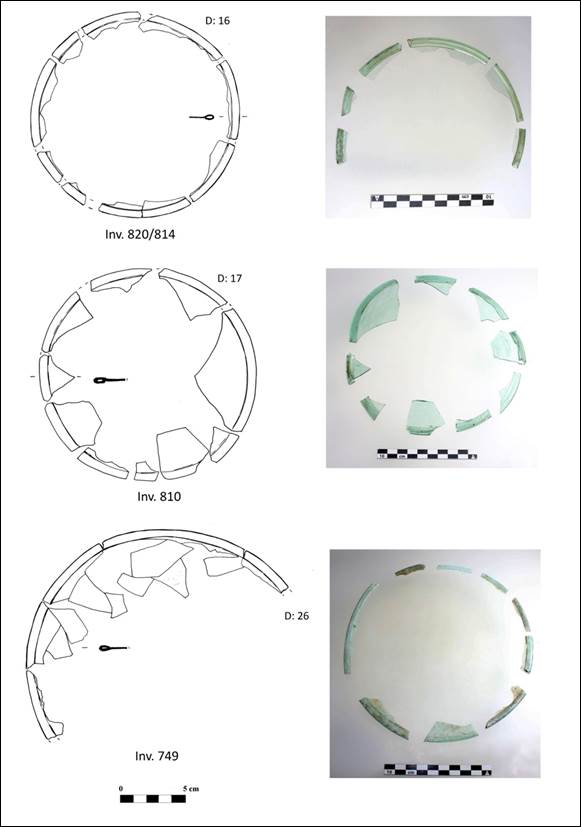

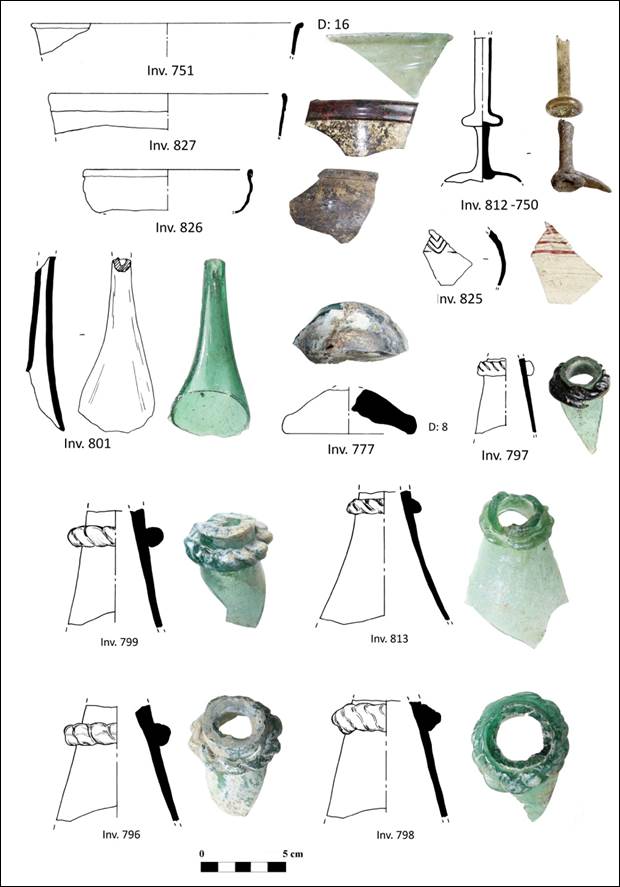

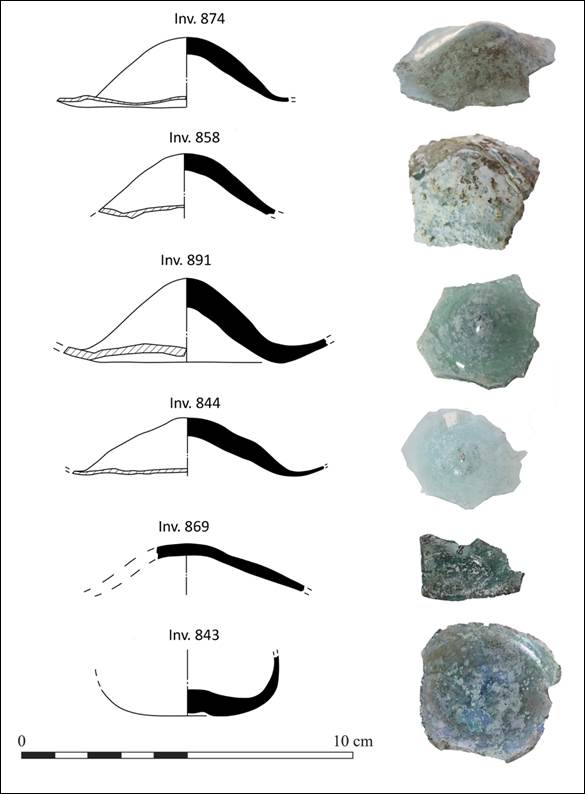

The bulk of glass finds includes 43 glass artefacts that can be divided into two categories: circular windows and tableware. The circular glass window panes, very small fragments, are of blue aquamarine, light green and green color. The tableware glass finds consist of fragments of rims and necks of jugs, bottles and bases. We also found fragments of a goblet of blue aquamarine color with the upper part of the stem; a bottle sprout of green color; a fragment of the base of a goblet; a fragment of the decorated wall of a goblet; a vase rim; a glass rim and tow rims of jugs, one of green color, the other one of brown and red color. Apart from a fragment of a dome-shaped coffer lid, in dark color and covered with patina, dated to the 15th-16th cent. AD., all the other finds are dated to the 10th -12th cent. AD.

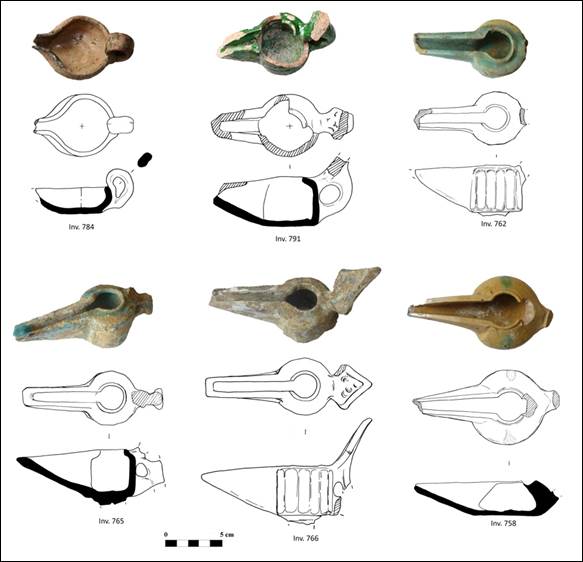

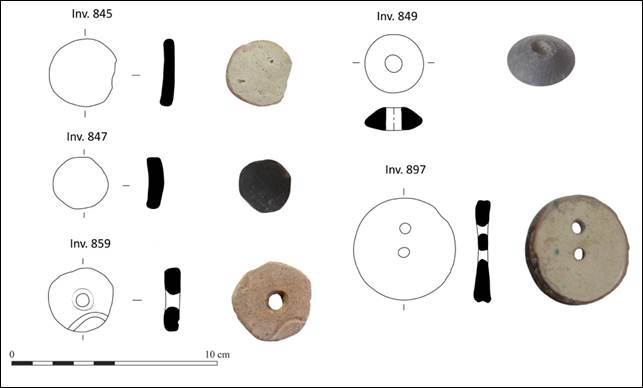

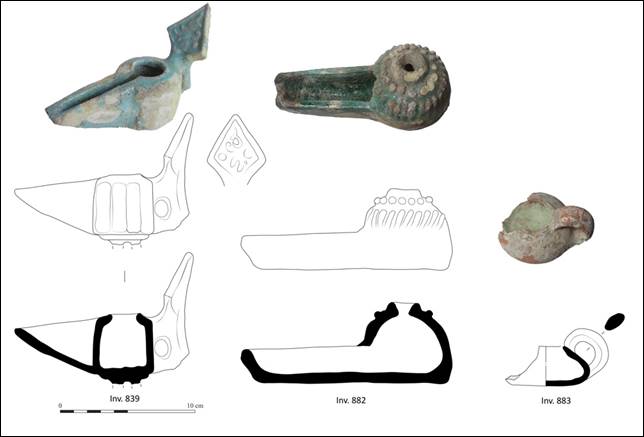

The terracotta finds include six glazed oil lamps, chirag, a dome-shaped button with a flat base, decorated with geometrical features, framed concentric lines, and dated to the 9th -10th century. One glazed turquoise bead and a small green and orange glazed coffer lid, dated to the 9th-10th cent. AD, was also found, as well as two spindle whorls made of the wall of a vessel. Both specimens should be dated to the Early Medieval period (5th -6th cent. AD). This year some architectural ornamentation, dated to the 10th -11th -12th cent. AD, has been unearthed: two pieces are fragments of rectangular baked bricks decorated with geometric patterns, probably parts of a portal frame. Another piece could have been part of the outer facade of the entrance of a palace. Then, two fragments of tiles with traces of paint, one with a red-colored surface, one of red ochre color.

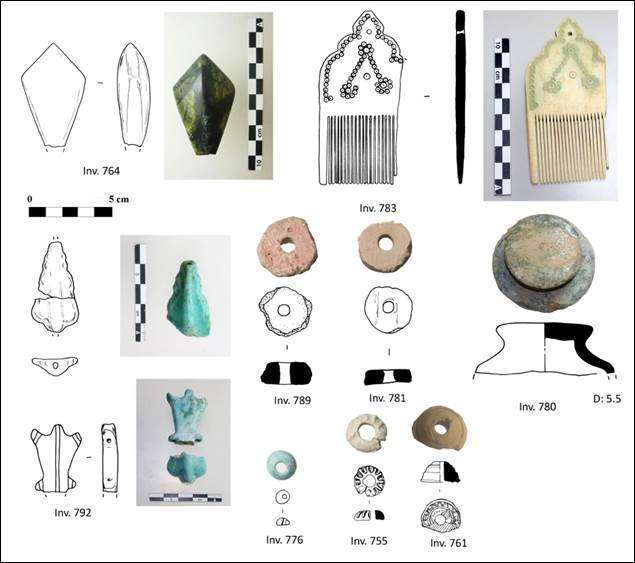

Among the stone finds unearthed this year there are a rhomboid pendant of dark green jasper, a round small bead with a flat base and a wavy grooved decoration, and finally a white translucent stone. Two faïence (kashin) pendants were found in hole SU1191, both dated to the 12th cent. AD. The first one, of turquoise color, has the shape of a torso; the left shoulder is missing. The second one, also of turquoise color, is triangular.

Among the bone finds, we have a fragment of a bone comb, dated to the 10th cent. AD. The specimen is decorated with little circles that run around all the top. A ring made of the vertebral column of a fish was also found.

Fig. 1 Vardanzeh 2019, citadel: general

plan with trenches excavated this year (in pink) (topography by S. Mirzaachmedov).

Fig. 2 Bath Area, room 47/trenches C8/sw CC8NE: SU1257 mud brick structure, bath unit SU1250, bath unit 1254, floor 1248,

wall1228, partition wall 1264, SU 1271 mud bricks structure, floor 1270, SU1273 drainage system, SU1279 pipeline (view from N).

Fig. 3 Trenches C8NW/C8SW: Bath

Area, room 47:wall1228,wall1242, hole 1247, mud bricks structure 1257, bath unit 1250, bath unit 1254 (view from S).

Fig. 4 Citadel,

trenches C8SW/probing trench CC9NE: wall 1126 (view

from E).

Fig. 5 General view (from W).

Fig. 6 Drainage system SU 1183 (view from W).

Fig. 7 Fragment of wall painting on the floor (view from N).

Fig. 8 General view (from N).

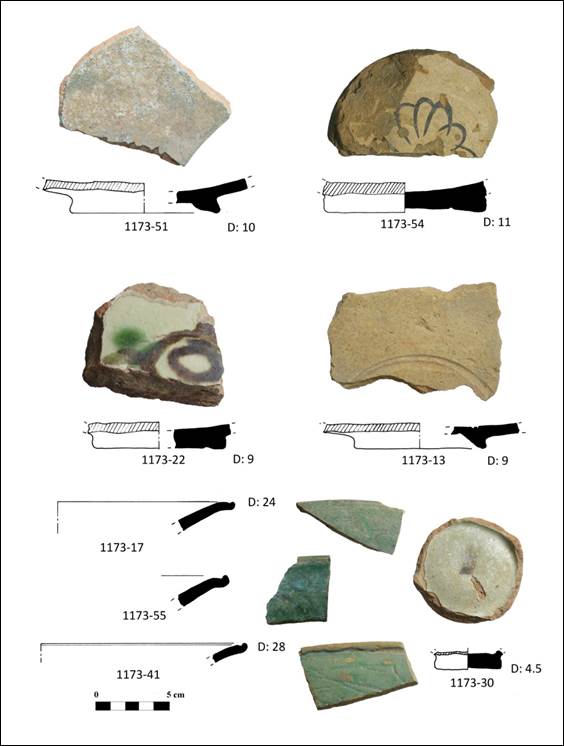

Fig. 9 Trench CC8SW, SU 1173: bases of glazed dishes (22, 51, 54, 13);

base of a glazed bowl (30); rims of glazed dishes (17, 41, 55).

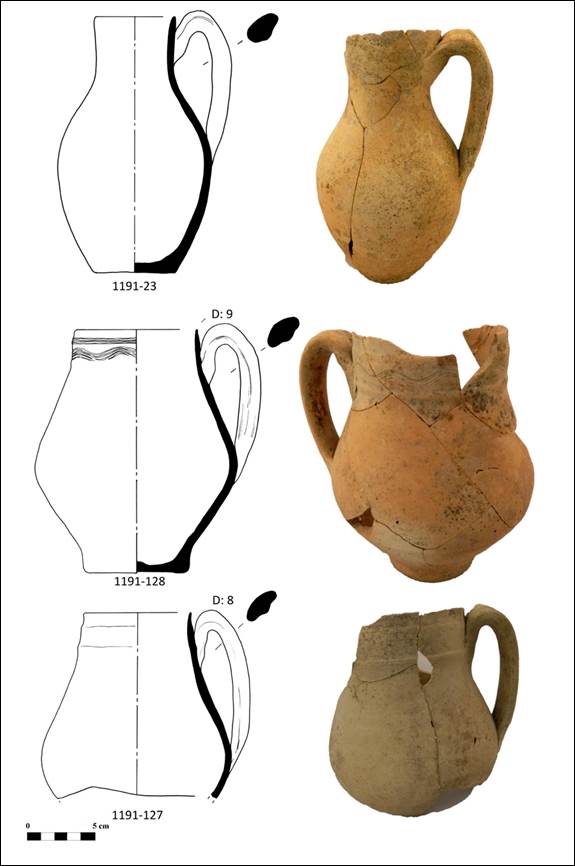

Fig. 10 Trench D8SE, SU 1191: juglets (123, 127,

128).

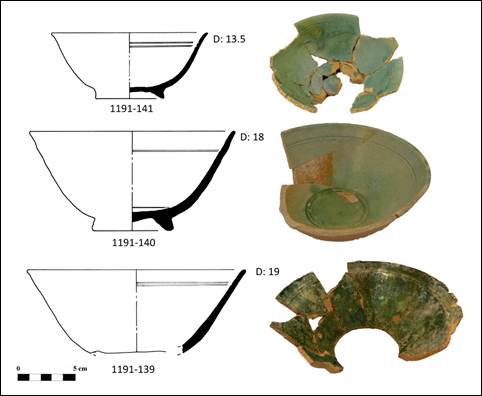

Fig. 11 Trench D8SE, SU 1191: glazed bowls (139, 140, 141).

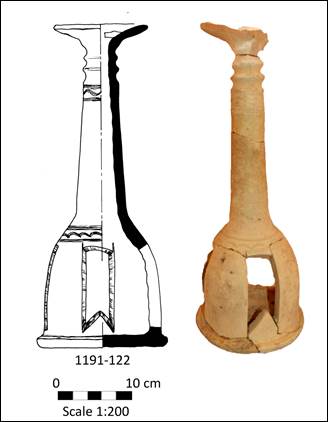

Fig. 12 Trench D8SE, SU 1191: lamp (122).

Fig. 13 Trench D8SE, SU 1191: small pots (121,

125, 129, 135); juglet (132, 135).

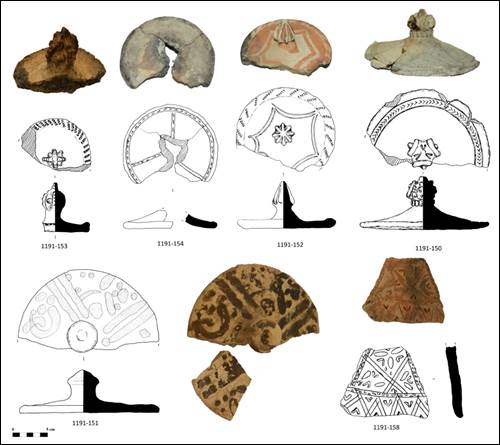

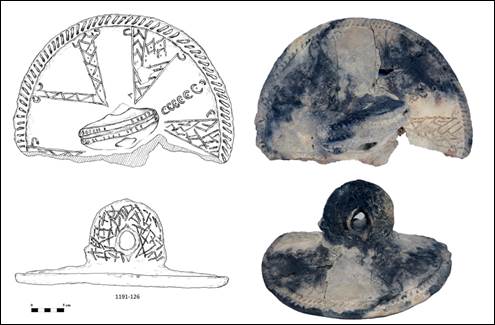

Fig. 14 Trench D8SE, SU 1191: modelled flat lid, decorated with stamped motifs (150,

153); flat lid decorated with painted, shaped and incised motifs (152, 158); flat lid decorated with painted motifs (151), bell-shaped lid, decorated with incised motifs.

Fig. 15 Trench D8SE, SU 1191: modelled lid, decorated with incised motifs (126).

Fig. 16 Trench C8SE, SU 1241: rim of jars (36, 37, 38); ovoid jug (31); base of a jar (32);

handle of a jug (40); glazed bowl (41); glazed dishes (33, 39); bell-shaped lid (34); flat lid decorated with incised motifs (35).

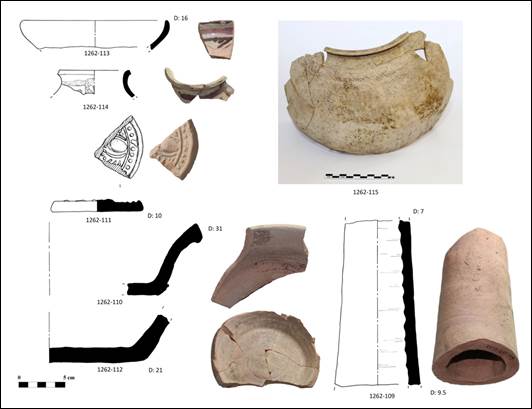

Fig. 17 Trench CC8NE, SU 1262: glazed bowl (113); small pot decorated with painted motifs (114); flat lid decorated with stamped motifs (111); basins (tagora) (110, 112); pipeline (kubura) (109).

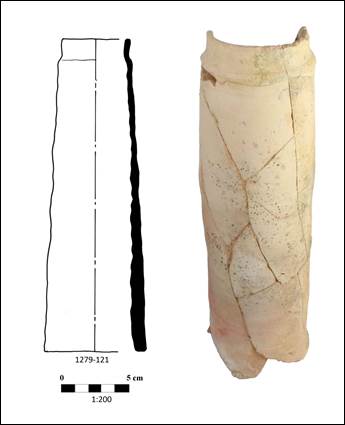

Fig. 18 Trench CC8NE, SU 1279: pipeline (kubura) (121).

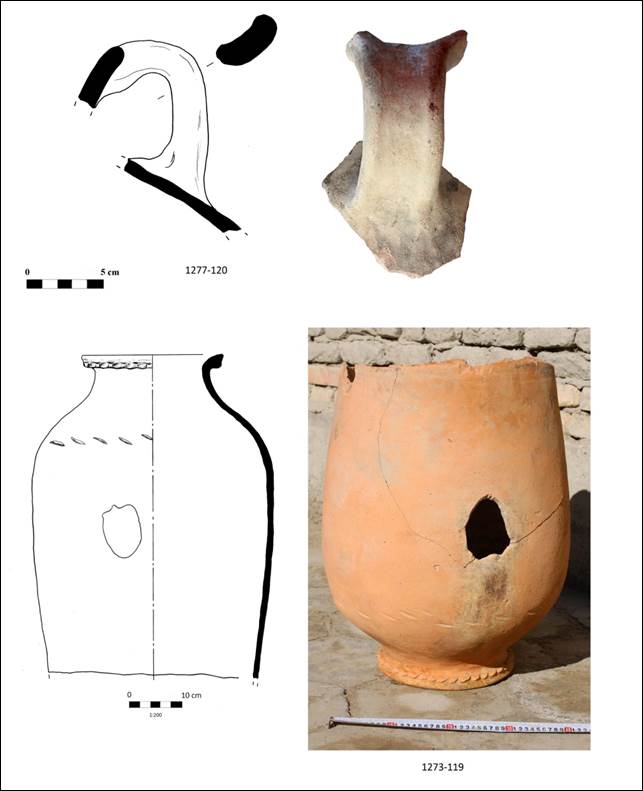

Fig. 19 Trench C8SE:

handle of a juglet (1277-120); trench CC8NE: storage jar re-used as pipeline (1273-119); trench CC8NE: pipeline (kubura) (1279-121).

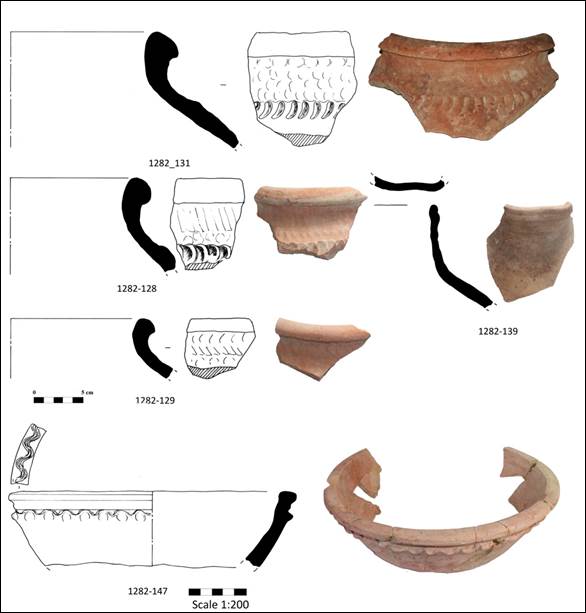

Fig. 20 Trench CC8SE-C8SW, SU 1282: rims of storage jars decorated with finger marks impressions (128, 129, 131); basin (tagora) (147).

Fig. 21 Coins: Khuwarizmshahs Anushteginid Muhammad b.Tekish coin (Inv. 833); Karakhanid coins (Inv. 753, 832); Janids Bukhara(?) coin (Inv. 775); falsification of a copper coin dated end 10th/early 11th AD (Inv. 788).

Fig. 22 Terracotta finds: glazed oil lamp (chirag) dated 10th century AD. It has a circular tank and a loop-shaped handle (Inv.784); glazed

green oil lamp (chirag)

with a circular oil tank (Inv.791; glazed turquoise oil lamp (chirag) with a circular multifaceted oil tank,

open in the upper part (Inv. 762); turquoise glazed oil lamp, the glazing very

damaged, with circular oil tank and open in the upper part (Inv.765); turquoise

oil lamp (chirag) with a multifaceted oil tank (Inv.

766); yellow brown glazed oil lamp (chirag) with two splashes of glazed green decoration on

both sides of the circular oil tank (Inv. 758).

Fig. 23 Rhomboid pendant

of dark green jasper (Inv.764); small stone bead with flat base (Inv. 755);

glazed turquoise bead (Inv. 776); turquoise faïence pendant (kashin), torso-shaped

(Inv.792); tourquoise faïence pendant (kashin),

triangular shape (Inv. 795); red buff ware: dome-shaped button with flat base

(Inv. 761); spindle whorl made of red buff ware

(Inv.781); spindle whorl (Inv. 789); green and orange glazed coffer lid (Inv.

780); bone comb (Inv.785).

Fig. 24 Various artefacts: cotton

fabric (Inv. 744); earth natural mineral pigment red ochre(Inv.747);

earth natural mineral pigment, ochre (Inv. 748); rectangular baked bricks

decorated with geometric patterns (Inv. 828); rectangular baked bricks decorated with geometric patterns; brick of the

architectural décor (Inv.730); rectangular ‘tile’ with traces of red paint (Inv. 782); rectangular ‘tile’ with traces of red ochre (Inv. 786); ring

made of the vertebral column of a fish (Inv. 790).

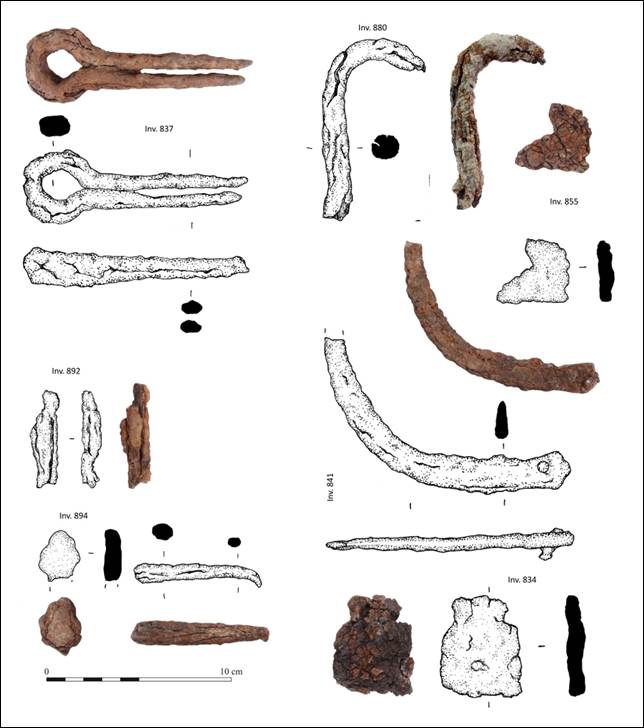

Fig. 25 Iron finds: knife blade (Inv.745,

769,783); arrow blade (Inv.763); fragments of nails (Inv.756, 759, 770, 773); dagger blade (Inv. 757,774); part of coating (Inv.772), door

locker (Inv. 767,793, 794);

objects of unknown use (Inv. 746, 752,760,768,783,831);

ring-shaped handle of a cosmetic pot (Inv.754).

Fig. 26 Glass finds: circular windows.

Fig. 27 Glass vessels: rims of bowls (Inv. 751, 826, 827); stem of a glass? (Inv. 850-712); wall of a vessel (Inv.

825); decorated necks of jugs (Inv. 797, 799, 813, 796,

798), spout of an alambic (Inv 801); lid (Inv. 777).

Due to Corona, no excavation could be carried out in Vardanzeh in 2020.

Due to local administrative difficulties, no excavation could be carried out in Vardanzeh in 2021. The excavations will be continued in summer 2022.

PRELIMINARY REPORT

ON THE 2022 FIELD WORK AT VARDANZEH

The eleventh archaeological excavation on the site of Vardanzeh, the ancient Vardana, was realized between August, 20, and September, 20, 2022, plus other two days devoted to complete the documentation (pottery, topography, finds).

The research staff was composed of four archaeologists: Silvia Pozzi, Ilaria Vincenzi, Makhsuma Niyazova and Dzamal K. Mirzaachmedov. Silvia Pozzi and Ilaria Vincenzi alternated their presence on the site: Pozzi worked the first half of the season, from the 20th of August to the 5th of September, while Vincenzi from the 6th of September until the end. Siroj Mirzaachmedov, architect employed at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand (now under the Ministry of Tourism of Uzbekistan) was in charge of the topographic documentation, using also photogrammetry techniques for a better representation of the excavated structures. Munira Sultanova, architect and conservator also working at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand, drew a selection of artefacts, for a total of 378 finds among pottery and small finds. The conservator, Dilmurod Kholov, was in charge of the cleaning and the conservation of metal artefacts and of an organic find unearthed this year.

The excavation of this year focused in the eastern part of the citadel and involved both new squares (CC7-SE, CC8-NW, CC8-SW, CC9-NW, CC9-NE, CC9-SW, CC9-SE) and already excavated squares that were further investigated (CC8-NE, CC8-SE, C8-NW, C8-SW), for a total surface of ca. 150 square meters. The decision to continue the investigation of this areahas been led because this sector is considered very promising for the general understanding of the history of the site. In fact, the stratification of the archaeological deposits was higher than in any other parts of the citadel and here we were able to trace the sequence of occupational phases at least from the Late Antiquity to the late 19th cent.

The present campaign of excavation gave us possibility to obtain important details for a better knowledge and understanding of the Early Medieval structures as well as of Medieval bathhouse, already identified in the past years.

Pozzi excavated the SE part of trench CC7-SE and the NW part of CC8-NE. Specific parts of trenches CC8-NE (SE quadrant), C8NE (SW quadrant), C8-SW (NW quadrant) and CC8-SE (NE corner), already opened in 2019, were further investigated. Trenches CC8-SW/CC8-NW/CC8-SE were excavated for first for first by Pozzi and then by Vincenzi (we will refer to this part labelling it the Northern trenches). Trenches CC9-NW, CC9-NE, CC9SE and CC9SE were excavated by Niyazova (we will refer to this part as the Southern trenches).

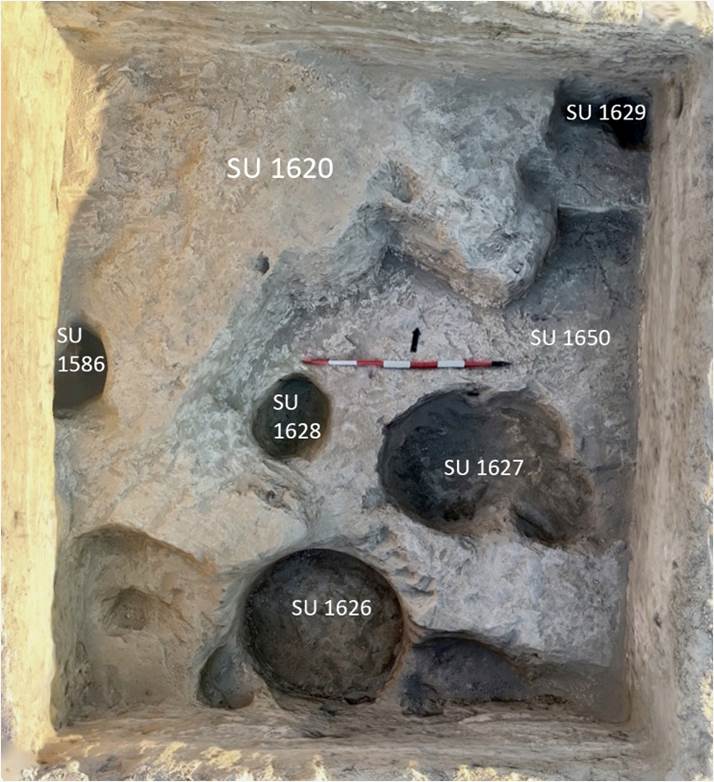

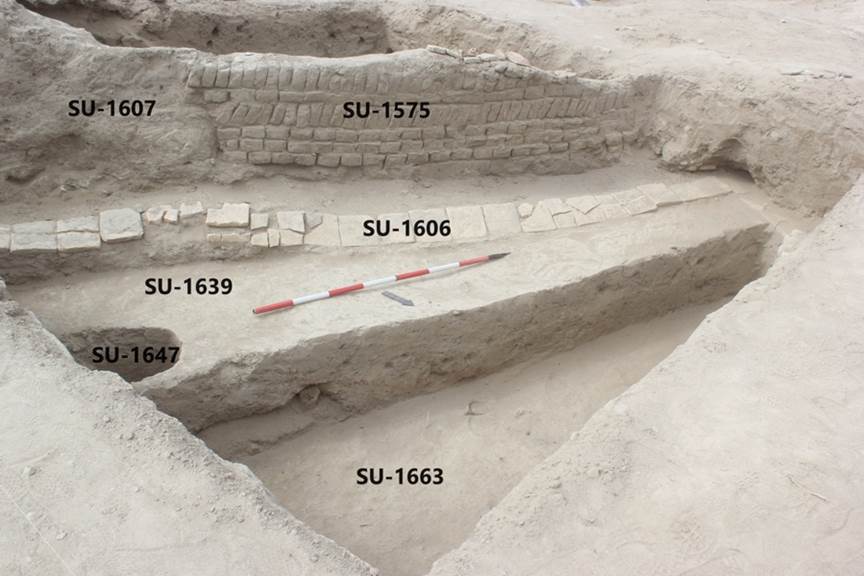

The features unearthed in the N trenches gave us a better comprehension of the complex canalization system related to the bath house built in the Samanid period 9th-10th cent. AD and in use, after underwent several reconstruction, till the 12th cent. AD. Several traces of canalization or drainage systems still in situ, made with interconnected tubular pipelines (kubura) or superimposed storage vessels re-used for this purpose (tashnau) have been found. Two elongated rooms, 49 and 50, as well as room/corridor 51 were probably part of the bathhouse. Room 49 evidenced the presence of a bath unit with a preserved tiled floor and at least other four bath units, as suggested by the drainage systems found there (tiled floors not preserved); room 50 has not a preserved floor. It was also remarkable the discovery of an iron making area that re-used a previous bath space, where a large quantity of iron slags was found. The removal of the structures related to the bath house clearly attested how this new architectural model was built: we detected both new walls as well as walls rebuilt on top and often reusing the early medieval structures, altering their original physiognomy.

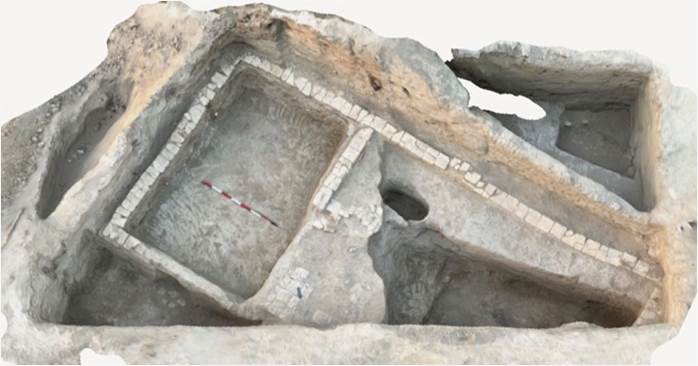

In the upper levels of the southern trenches we met a similar situation, i.e. a series of medieval holes both used as pit holes as well as drainage systems. Very interesting it is a circular structure realized with trapezoidal baked bricks, probably a well for the water supply or a sort of granary. As far as the early medieval phase is concerned, in two different trenches we identified the mud brick platforms that belonged to the last phase of occupation of the early medieval palace, when this area was reconverted into storage rooms. Another significant result concerns the identification, of two rooms (52 and 53) that belonged to the first building phase of the palace (the moment of its foundation). Also part of the eastern corridor of surveillance of the early medieval palace was exposed.

POTTERY

This year a total of 3.073 pottery fragments were unearthed, among them 2.309 un-diagnostic (75%) and 762 (25%) diagnostic potsherds: the majority is represented by un-glazed ware (98%) and only the 2% consisted in glazed ware. The analysis of the functional classes within the diagnostic pottery unearthed this year evidenced, as usual, that the most common class is represented by the storage ware (63%), followed by the un-glazed table ware (23%). The pottery used for drainage systems (pipelines, storage ware reused for drainage system) represents overall the 5 % while the cooking ware represents only the 4%. The glazed tableware represents the 3%, while a very small percentage is represented by oil lamps and pottery used for specific purposes (trays, sanitary).

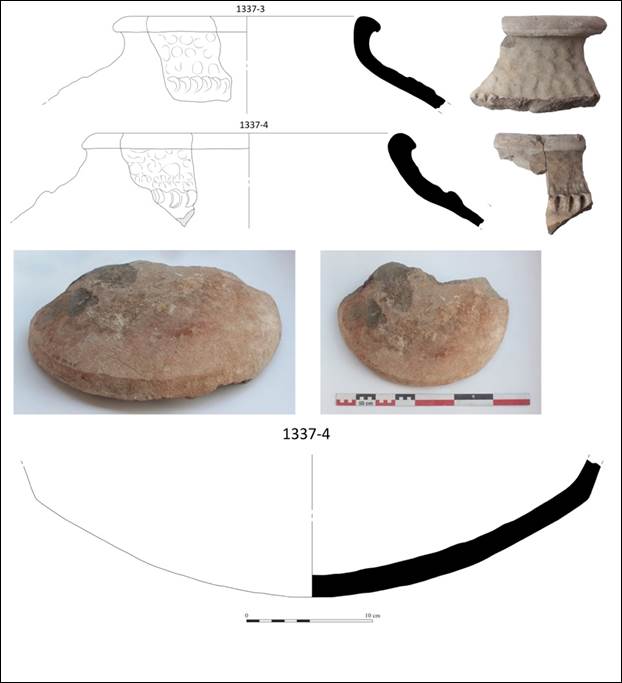

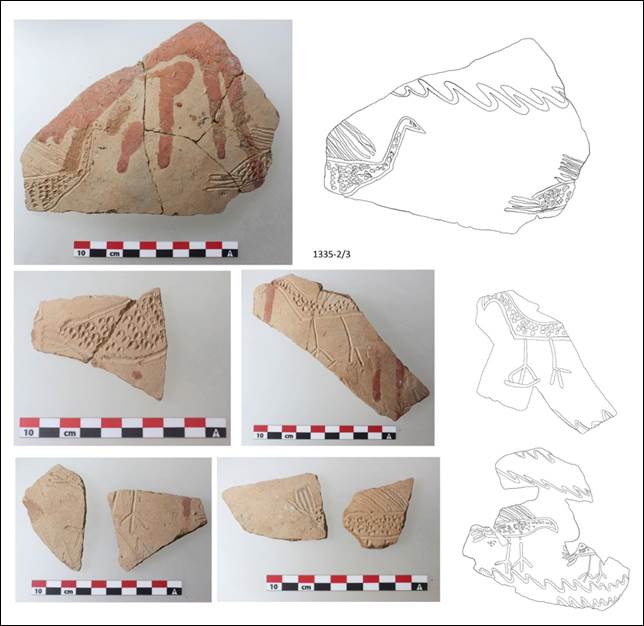

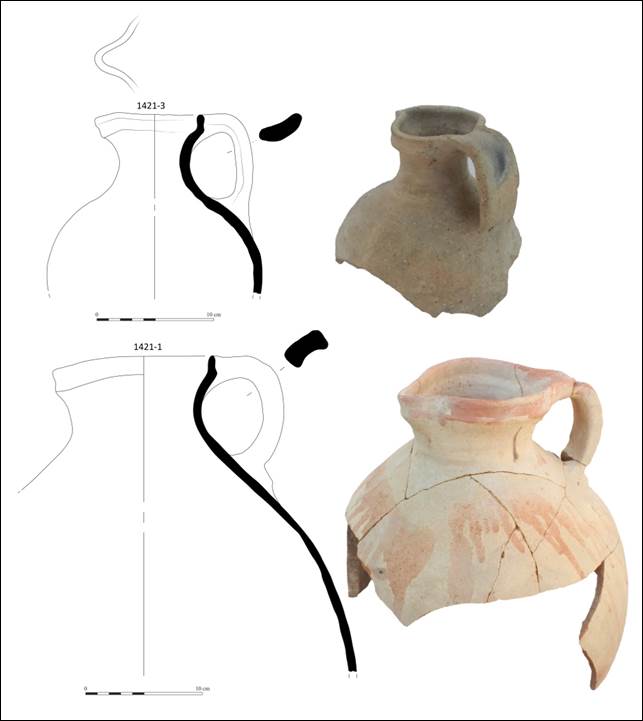

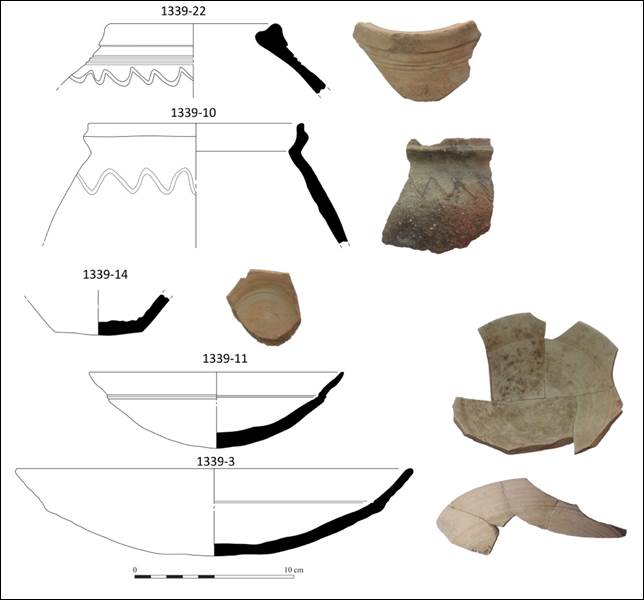

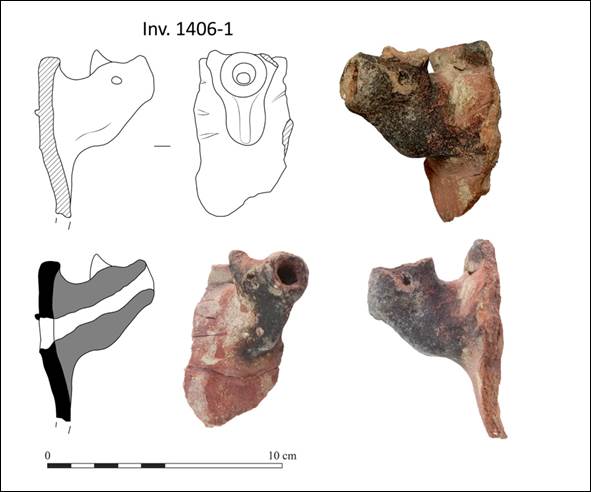

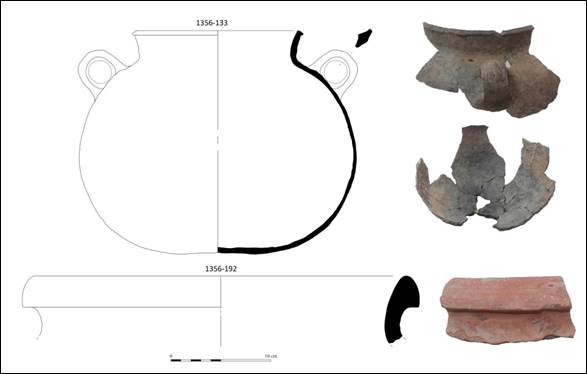

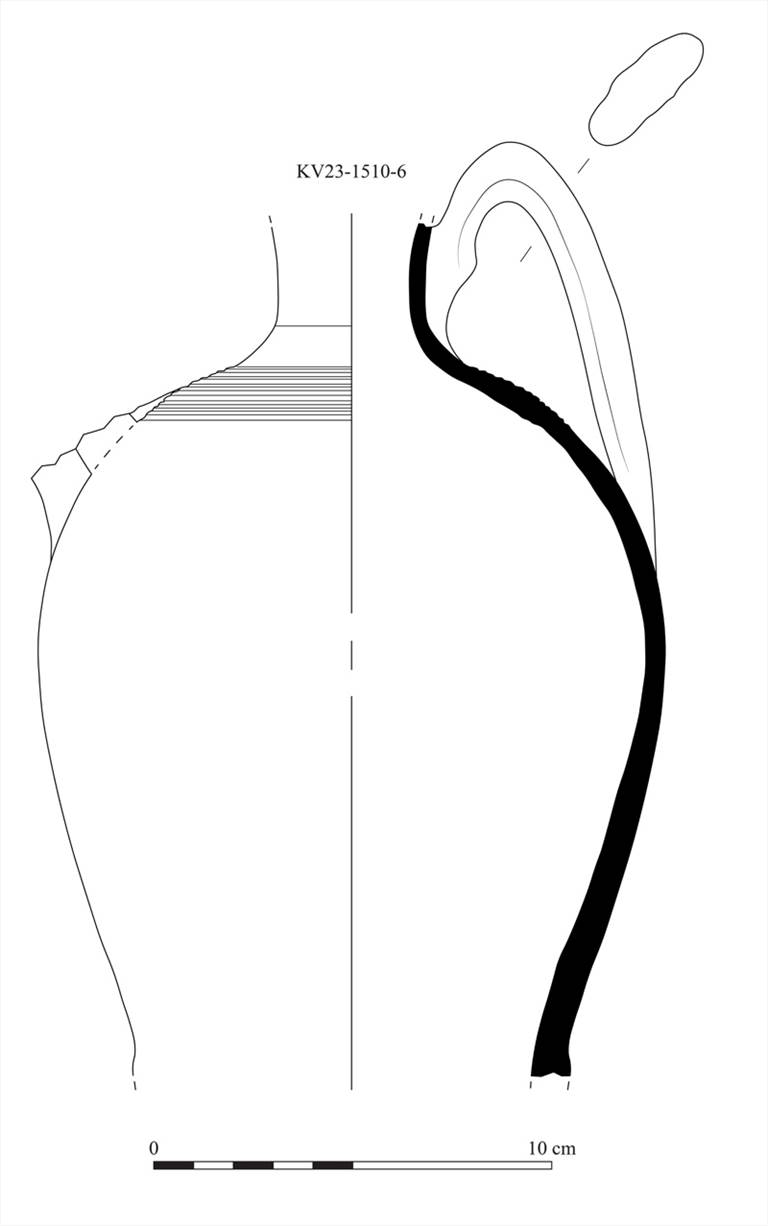

Pottery found this year includes specimens dating from the 5th to the 19th cent. AD. The pre-Islamic ware includes mainly finds dating to the 7th-8th cent. AD and few specimens dated to the 5th – 6th cent. AD. The majority of the storage vessels are wheel-made and includes well-know shapes of jars and of jugs. The most common category of jar is that characterized by an ovoid body, a short neck and a beak like rim (Fig. 17). The jars, usually covered with a pale slip, are decorated with one or more rows of elongated finger mark impressions and red paint drained on the upper part of the vessel. Some specimens probably dated to the 5th-6th cent. AD have a more rounded rim section and circular finger marks decorations. Also globular jars without neck were unearthed: this shape, usually characterized by an inset for the lid and holes for ventilations, is made of fine fabric and more rarely of rough fabric (Fig. 20: 1339-22). We found also some necked jars with inset for the lid, characterized by a rougher fabric. One specimen, found fragmented, had a rounded base, red stripes of paint and beautiful birds incised on the body: realized with schematic traits, the birds should have decorated the whole vessel, since we recognized at least five animals (Fig. 18). As far as the storage jugs are concerned, we found several examples of large jugs made of the same fabric of the jars that have circular mouth (diam. 10-12 cm) and a modelled spout (Fig. 19). The tableware includes both juglet and bowls, usually wheel made and realized with a fine fabric. As far as the juglets, we have globular vessels with circular mouth (diam. ca. 8 cm) and thickened rim, specimens with short but large neck and collared like-rim characterized by a modelled spout, as well as narrow-necked jugs with elongated mouth of ca. 5 cm in length (Fig. 23). Looking at the bowls unearthed this year, all made in fine ware, we have and example of high trunk conic bowl with straight walls as well as low trunk conic vessels, indistinct rim marked outside a carination and flat base externally ‘cut’ with a knife (Fig. 20: 1339-3). A specimen that deserves a special mention is a beautiful spout of a bowl, modelled with the shape of a bovine protomae (Fig. 21). The open mouth is realized with a circular hole, the ears are pointed (one is broken) and the eyes incised. The lower part of the neck is modelled with the typical shape of the bulls and both the neck and the mouth are blackened. This find has analogies with similar fragments from the 7th-8th cent. AD layers of Pendjikent. The pre-islamic cooking ware is represented by very few finds, the most representative one is an archaeologically complete modelled pot with two handles, of globular shape, made with a rough fabric very peculiar in the last early middle ages production (Fig. 23: 1356-133).

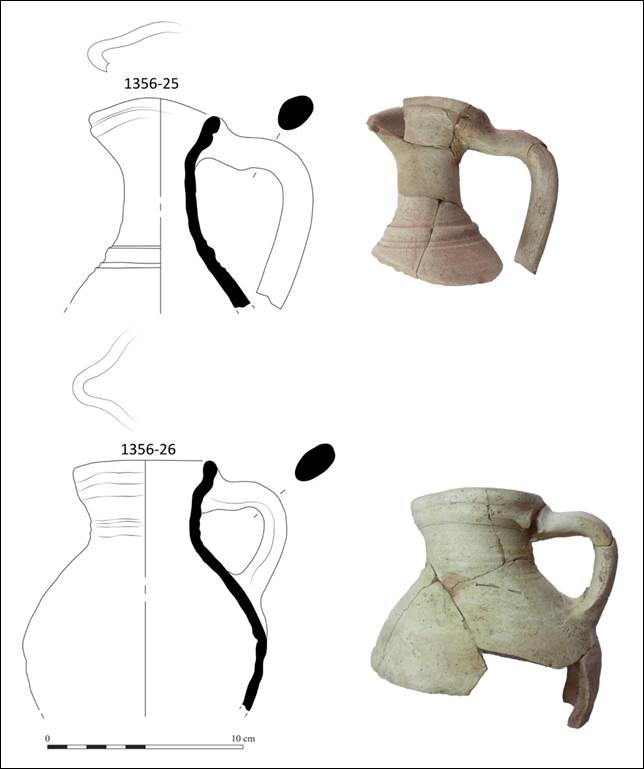

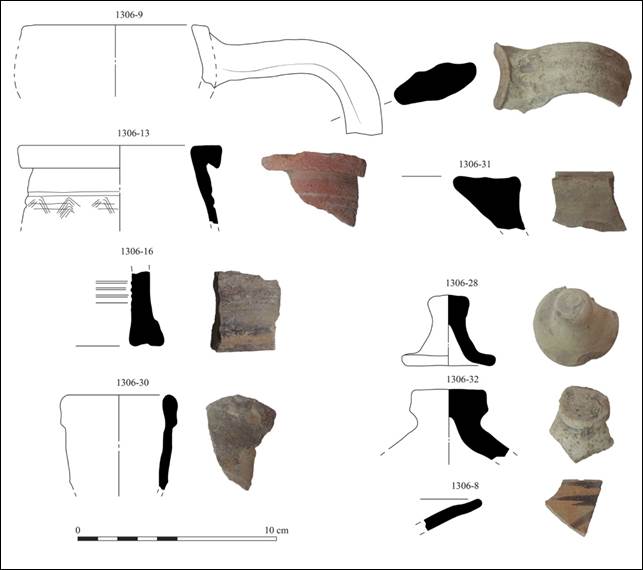

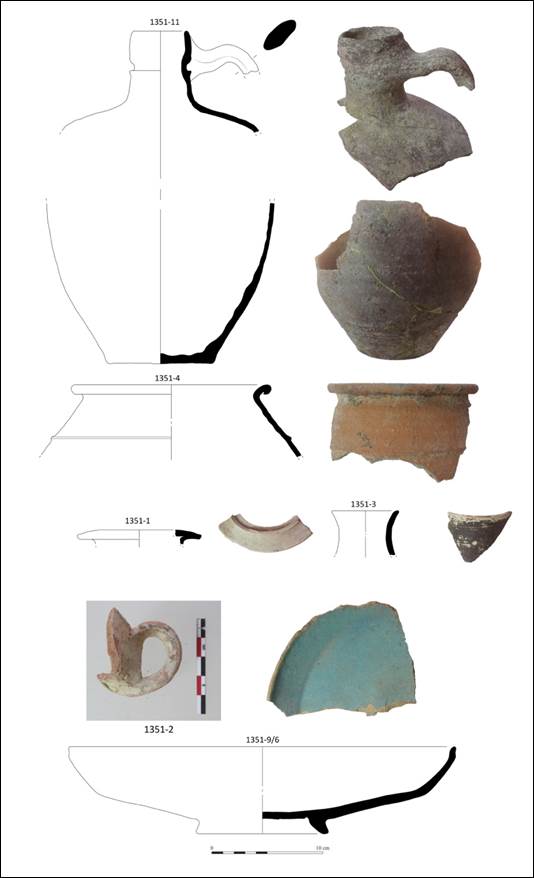

The Islamic ware includes both glazed and unglazed vessels dating from the 9th to the 19th cent. AD (Figg. 24-29). Pottery dating to the 9th-10th cent. AD includesseveral fragments of tableware, as handles and bases from table jugs. Made of fine ware, the handles were often decorated with a twisted motif. The storage ware includes large jugs with tapered handle profiles, used to carry or store water (Fig. 26: 1351-11). We have also examples of small basins with sub-triangular rim and lids, both flat and bell-shaped. As far as the cooking ware is concerned, we found fragments of cauldrons and ovens characterized by flat base and tapering wall rising upwards, with corrugated horizontal comb lines for better adhesion of the dough.

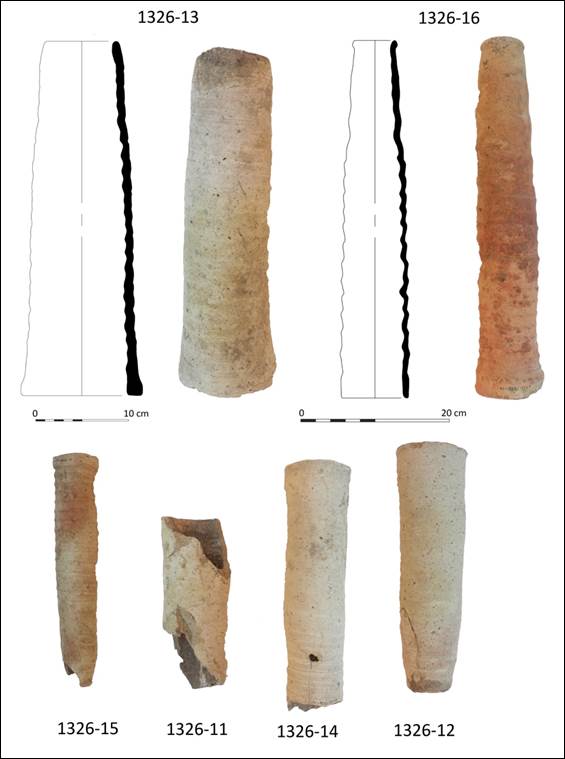

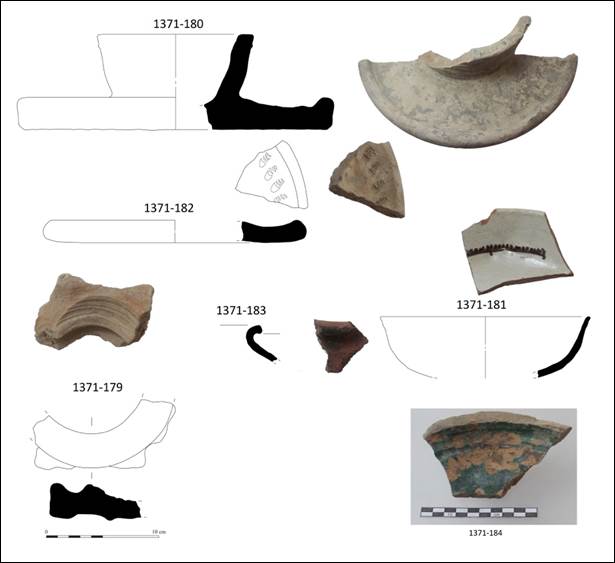

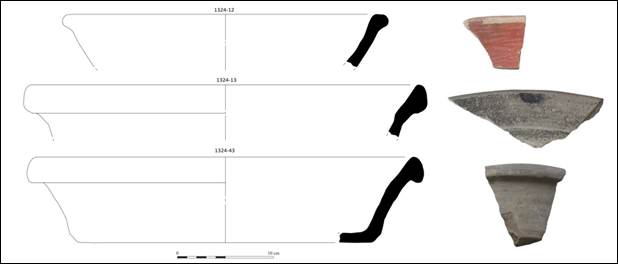

Pottery dating to the 10th-12th cent. AD includes several examples of storage ware, mainly large jugs for conservation or transport of the waters, the handles decorated with ribbon like motifs and covered with grey and reddish slip. We have also found jars, a lid of jar and basins that can have red or black slip, or they can be without slip. This shape was used both for washing purposes, as in the case of the large vessels, as well as for kneading dough, when the size was smaller. Another category is constituted by the open mouth large vessels, characterized by flat reverted rim decorated with modelled motif. Among the lids, we have bell-shaped lids, used in jug-shaped vessels, a modelled lid with a modelled motif on the rim. The tableware includes mainly jug and a fragment of a bowl-shaped vessel decorated with stripes and spots of dark red slip paint. Examples of cooking ware are cauldrons, jugs for boiling waters and ovens. Among the glazed ware, we found dishes with green or turquoise glaze (Fig. 26: 1351-9/6), bowls with olive background or with turquoise glaze. Dating from the 9th to the 12th cent. AD are also several examples of tubular pipelines used in canalization systems (Fig. 16), as well as several examples of storage vessels re-used for the same purpose (Fig. 29).

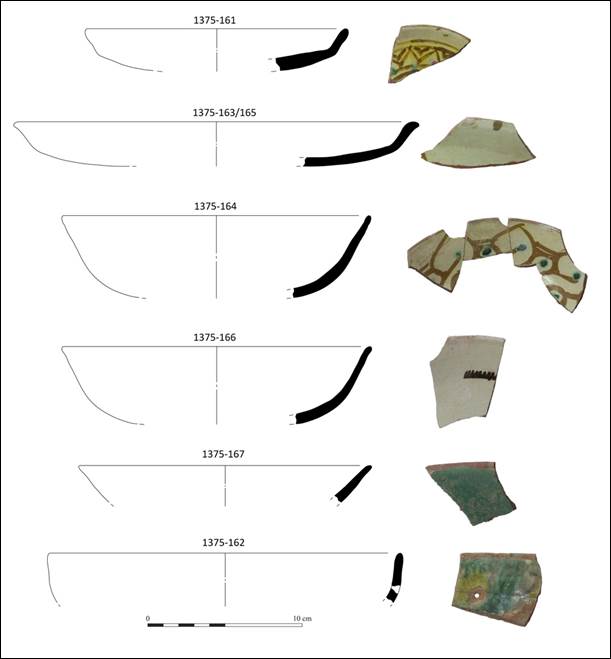

Among the pottery dating to the 18th – 19th cent. AD we have mainly dishes decorated with linear or vegetal scratched motifs along the walls and the rims and covered by low quality glazing (Fig. 24: 1375-162-167). The glazing can be dark green, yellow or they can have a yellow glaze with spots of green paint.

Finds

The corpus of the finds unearthed during the archaeological excavation of this year a total of 64 inventoried finds, among metal objects, glass, terracotta, stones, mineral finds and organic materials. The majority was unearthed inside the medieval contexts (9th-12th cent. AD).

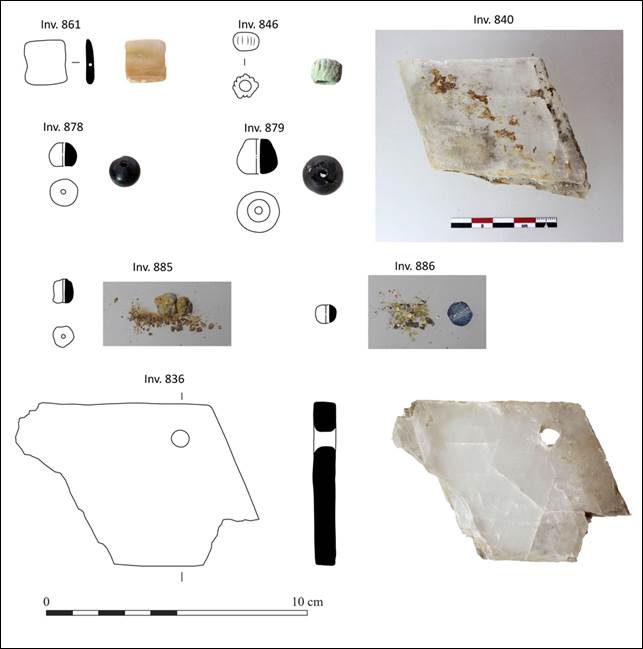

All the iron finds were covered by rust and some of them were also broken. The majority belong to the category of tools: fragments of straight blames, a curved blame probably a broken knife, hooks, nails, door bolts, two object objects of unknown use and a broken arrow head. We found also slags of amorphous shape, of grey colour and a wavy surface characterized by bubbles, a typical result of a smelting process. The bulk of the glass find includes a narrow necked juglet of light green color, found fragmented. The upper part, still well preserved, shows a rim characterized by an elongated spout, positioned on a tapered neck decorated with horizontal and protruding ribbons. We have also a small handle of a juglet, of green color, the concave bottom part of glass vessels of light green color, always covered with an iridescent patina, and some fragments of circular glass windows of turquoise color. The glass past (kashin) finds include a very small cylindrical bead of turquoise color, decorated with vertical ribbons, and a spherical bead of blue color, covered by a tiny gold polish very badly preserved. The terracotta finds include oil lamps (chirag), tokens, spindle whorls and baked bricks with special shapes. Under the category organic finds we have the circular base of a basket made of intertwined straw, found on the floor of the storage room dating to the early medieval period. The specimen was preserved thanks to the fire that interested this area and it is still visible the texture of the basket and the knots. A quadrangular bead in nacre, of pale yellowish color, was also found. The stone finds unearthed this year we have two very similar flat slabs of crystal, in almost trapezoidal shape of white color and transparent. We found also two beads in jet (known also as lignite or gagate), a sedimentary rock of vegetal origin.

Flotation

This year we collected several litres of sediment samples that were floated in the fieldwork using an overflow machine, collecting both heavy and light fraction samples. The material will be further processed and then sent to Jena, (Germany) for archeobotanical analysis that will be led by the team directed by Dr. R. Spengler (Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History), who is carrying on the study of ancient Central Asian flora. This is the second year that Vardana participate to this study. Particularly promising are the samples collected from the storage area dating to the 7th-8th cent. AD, fired during the Arab conquest of the region. Well visible on the floor on this area, as well as under the storage jar found still in situ, a very large quantity of seeds was found, among them rests of lentils, barley and nuts.

Fig. 1 Vardanzeh, genarl plan of the citadel

and the trenches excavated in 2022 (in pink) (Topography by S. Mirzaachmedov on Cerasuolo plan).

Fig.

2 Eastern sector, plan

updated to the 2022 (Topography by S. Mirzaachmedov).

Fig. 3 Trenches CC8-NE/C8-NE: medieval drainage

systems (view from N).

Fig. 4 Trenches CC8-NE/CC8-NW: Top view.

Fig. 5 Trenches CC7-SE/CC8-NE: early medieval

remains from the storage area (top view).

Fig.

6 Trenches CC7-SE/CC8-NE:

mud brick platforms under the early medeival floors

of the storage area (top view).

Fig. 7 Trenches CC8-SW/CC8-NW: early medieval mud

brick platforms (view from SE).

Fig. 8 General view at the end of the excavation.

Fig. 9 Trenches CC8-SW/CC8-NW: drainage system SU

1342 (view from E).

Fig. 10 Trenches CC7-SE/CC8-NE: drainage system (view

from E).

Fig. 11 Trench CC9-SW: mud brick platform SU 1373

(view from E).

Fig. 12 Trench CC9-NW: room 52 (view from W).

Fig. 13 Trench CC9-NW/CC9-SW: room 53 (view from

W).

Fig. 14 General view at the end of the excavation.

Fig. 15 General view at the end of the excavation.

Fig. 16 Trenches CC7-SE/CC8-NE: tubular pipelines

(kubura).

Fig. 17 Trenches CC7-SE/CC8-NE: rims of storage

jars (1337-2/3); rounded base of storage jar (1337-4).

Fig. 18 Trenches CC8-NW/CC8-SW: storage jar

decorated with incised birds (fragments from the same vessel).

Fig. 19 Trench CC8-SW: large storage jugs.

Fig.

20 Trenches CC8-NW/CC8-SW:

cooking pot (1339-10); bowls (1339-3; 1339-11); base of a jug? (1339-14);

globular jar (1339-22).

Fig. 21 Trench CC8-SW: spout of a cup decorated with

bine protomae.

Fig. 22 Trench CC9-NW: cooking pot (1356-133);

storage jar (1356-192).

Fig. 23 Trench CC9-NW: table jugs.

Fig. 24 Trench CC9-NW/CC9-SW: glazed dishes.

Fig. 25 Trenches CC7-SE/CC8-NE: jugs (1306-9, 1306-30); pot (1306-13); jar (1306-31); oven (1306-16); lids (1306-28-32); glazed dish (1306-8).

Fig. 26 Trench CC9-NW: jug for boiling water (1351-11); thin walled pot

(1351-4); table jug (1351-3); jug? (1351-1); oil lamp? (1351-2); glazed dish

(1351-6/9).

Fig. 27 Trenches CC9-NW/CC8-NW: tray (dastarkhan)

(1371-180); lid (1371-182): cooking pot (1371-183); glazed bowl (1371-181);

glazed dish (1371-184).

Fig. 28 Trench CC8-SW: basins.

Fig. 29 Trench C8-NW: Storage pot (1435-2);

storage jug re-used as pipeline (1435-2).

Fig.

30 Iron finds: door bolt

(Inv. 837); hook (Inv. 880); curved blame (Inv. 841); broken straight blames

(Inv. 834, 855); broken knife? (Inv. 894); unknown object (Inv. 882).

Fig.

31 Glass finds: juglet

(Inv. 839); glass window (Inv. 875); very ruined fragments of glass (Inv. 877);

handle of small glass vessel (Inv. 852).

Fig. 32 Glass finds: bottom part of glass vessels.

Fig. 33 Terracotta finds: tokens (Inv. 845-847); spindle

whorls (Inv. 849-859); weight loom? (Inv. 897).

Fig. 34 Terracotta finds: oil lamps (chirags).

Fig.

35 Various finds: nacre

bead (Inv. 861); glass paste bead (Inv. 846-866); jet beads (Inv. 878-879);

terracotta bead (Inv. 885); crystal slabs (Inv. 836, 840).

Fig. 36 Team workers.

Fig. 32 Team workers.

The Society for the Exploration of EurAsia (Switzerland)

Samarkand Archaeological Institute named after Y. Gulomov under

the cultural Heritage Agency of Republic of Uzbekistan

THE WEST SOGDIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION

AT VARDANZEH (ANCIENT VARDĀNA)

REPORT ON THE 2023 FIELD WORK

Directors

Džamal K. Mirzaahmedov, Silvia Pozzi

Field director

Ilaria Vincenzi

Research staff

Junior archaeologists: Orifhoja Muminov, Nishonboy Qulboyev

Architect and topographer: S. Mirzaahmedov

Artifact draft woman: M. Sultanova

Conservator: D. Kholov

INTRODUCTION

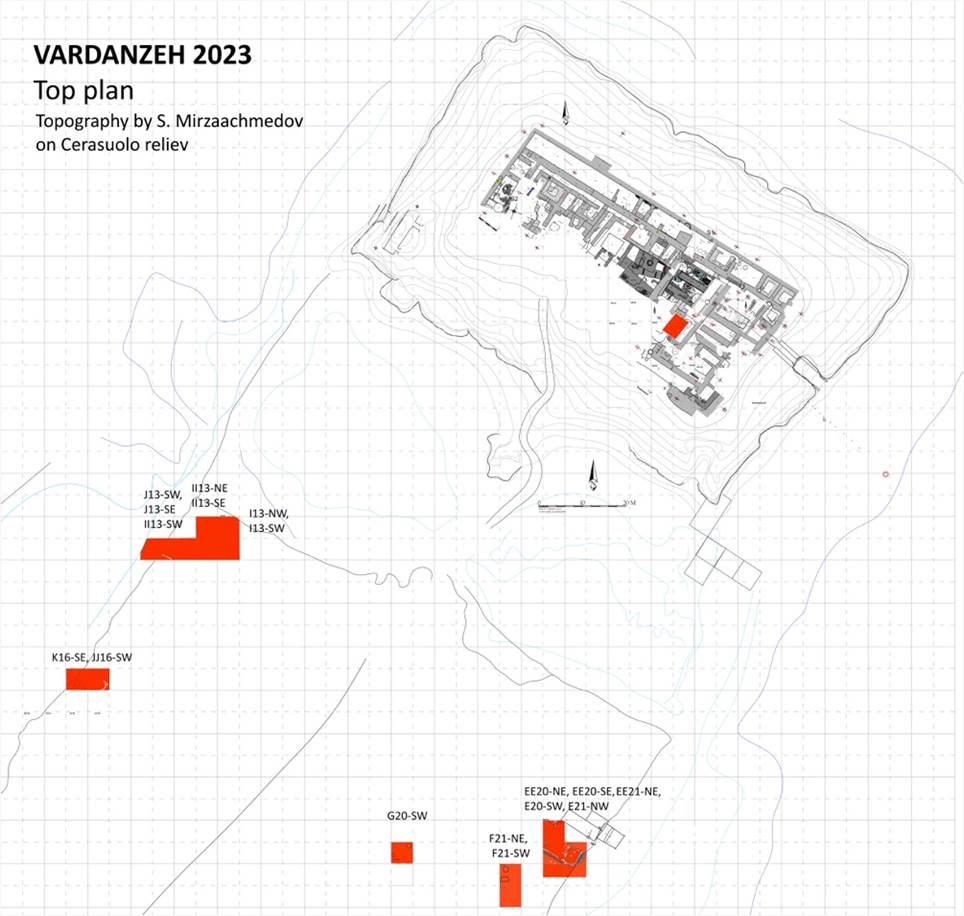

The twelfth archaeological expedition at Vardanzeh was realized between August, 19, and September, 20, plus other full 4 days devoted to complete the graphic and photographic documentation, as well as to the pottery database. The activity focused on the lower city (shahristan) located to the south from the citadel. At Vardanzeh the shahristan is formed by two distinct areas, one of quadrangular shape, located to the south from the citadel and separated from it by a deep moat, and a second area that spreads irregularly to the south from the previous one. We conventionally labeled these two areas shahristan 1 (the northern one) and shahristan 2 (the southern one). This year the shahristan 1 was investigated extensively, opening trenches both to the west and to the east from the street that runs trough the whole shahristan and ends to the citadel (Fig. 1). This street, detached from the main road located southwards, is modern but it is not excluded it overlapped an older one. The area to the west of the street was labeled ‘Shahristan 1-West’ and the one to the east ‘Shahristan 1-East’, in order to facilitate the localization of the excavated squares.

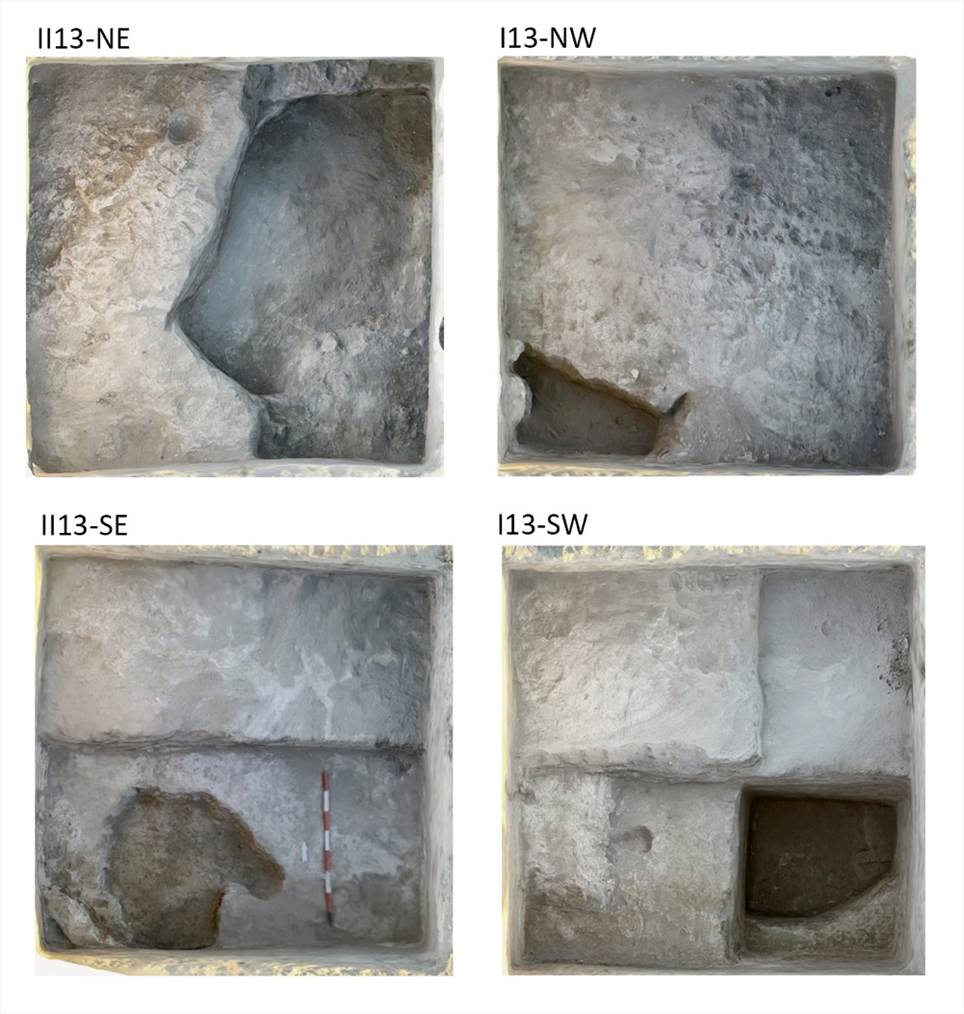

Following the topographic grid system we opened 9 squares in the Shahristan-1 West and 7 squares in the Shahristan-1 East (Fig. 2). Each square measured 5x5 m, for a total surface of 400 m2, with adjoining squares separated each other by balks 1 m wide. A localized excavation interested the citadel as well: we opened an area of ca. 9 m2 in the eastern part of the citadel.

This year research staff was composed of five archaeologists: Silvia Pozzi, Ilaria Vincenzi and Dzamal K. Mirzaachmedov in quality of senior archaeologists. Two PhD students, Orifhoja Muminov and Nishonboy Qulboyev, from the National Center of Archaeology of Academy of Science of the Republic of Uzbekistan based in Tashkent, took part to the excavation in quality of junior archaeologists. Siroj Mirzaachmedov, architect from the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand, was in charge of the topographic documentation, using also photogrammetry techniques for a better representation of the excavated structures. This year we introduced 3D Lidar technology using Polycam application available for free in Ipad Pro. This instrument allowed us to make measurable 3D reliefs of the stratigraphic units and structures. A daily documentation trough this tool has revealed a valid support in addition to the more traditional documenting techniques.

Munira Sultanova, architect and conservator also working at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand, drew a selection of artefacts, among pottery and small finds. The conservator, Dilmurod Kholov, was in charge of the cleaning and the conservation of metal artefacts unearthed this year.

Activites and results

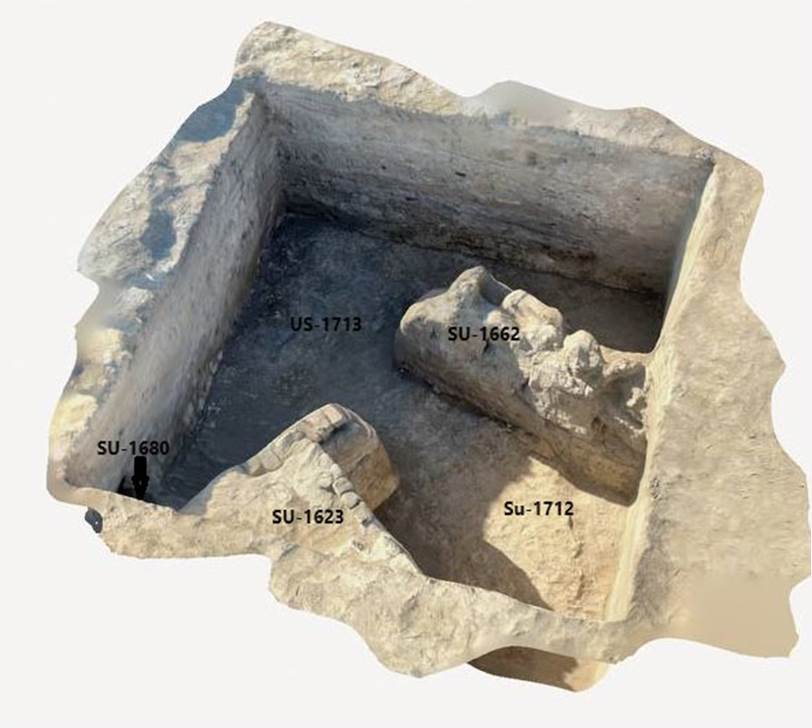

On the citadel, the activities carried on the eastern area put in light the late antique structures buried under meters of pebbles and sand deposits. Two underground galleries labeled Gallery A and Gallery B with Corridor N and Corridor S to it connected; remains of the roof of the gallery A made in three-four layers of mud bricks put in horizontally (Figg 4-6). The underground system of galleries should have been connected to rooms and halls and traces of similar features were already detected in the past years in other parts of the citadel, attesting the existence of a net of galleries probably connected with the eastern gate of the citadel. It is not excluded that the eastern gate could have represented, at a given moment, the main entrance of the citadel, without excluding the existence of more upper passages/exits leading to the Early Medieval Palace.

The lower city has been investigates extensively, both in its western and eastern sides. It was ascertained that the most recent traces of a stable occupation are dated to the late 19th – beginning of the 20th cent. AD, as attested by the recovery of several glazed and unglazed pottery finds dated to this period, as well as a large quantity of iron fragments (tools, buckets), oil lamps, shoes, traditional Uzbek hats made of cotton, terracotta toys and many other finds.

On Shahristan 1-West the pottery found in the lower phases can be dated at the Early Medieval Period and consisted mostly in potsherd of storage and tableware ware. All trenches, in their upper layers, are characterized by series of deposits of compact clay and soft soils with traces of burning, charcoal, kilns, drainage systems and a lot of ceramics dated late 19th - early 20th cent (Figg. 7-12). A interesting bulk of 72 bronze coins, mainly formed by Russian kopeks and Bukhara late emir coins was found at this level, directly on a floor and close to the remains of a tree and to two glazed cups (Fig. 6). This feature would suggest that this area could have been a sort of holy place where locals left small coins as devotional offerings. Instead, the lower layers were very compact and hard to excavate: these features, that we cannot still label platform, let us assume that their function could have been that of sealing the previous phases (i.e. the EMP) of the life of the shahristan.

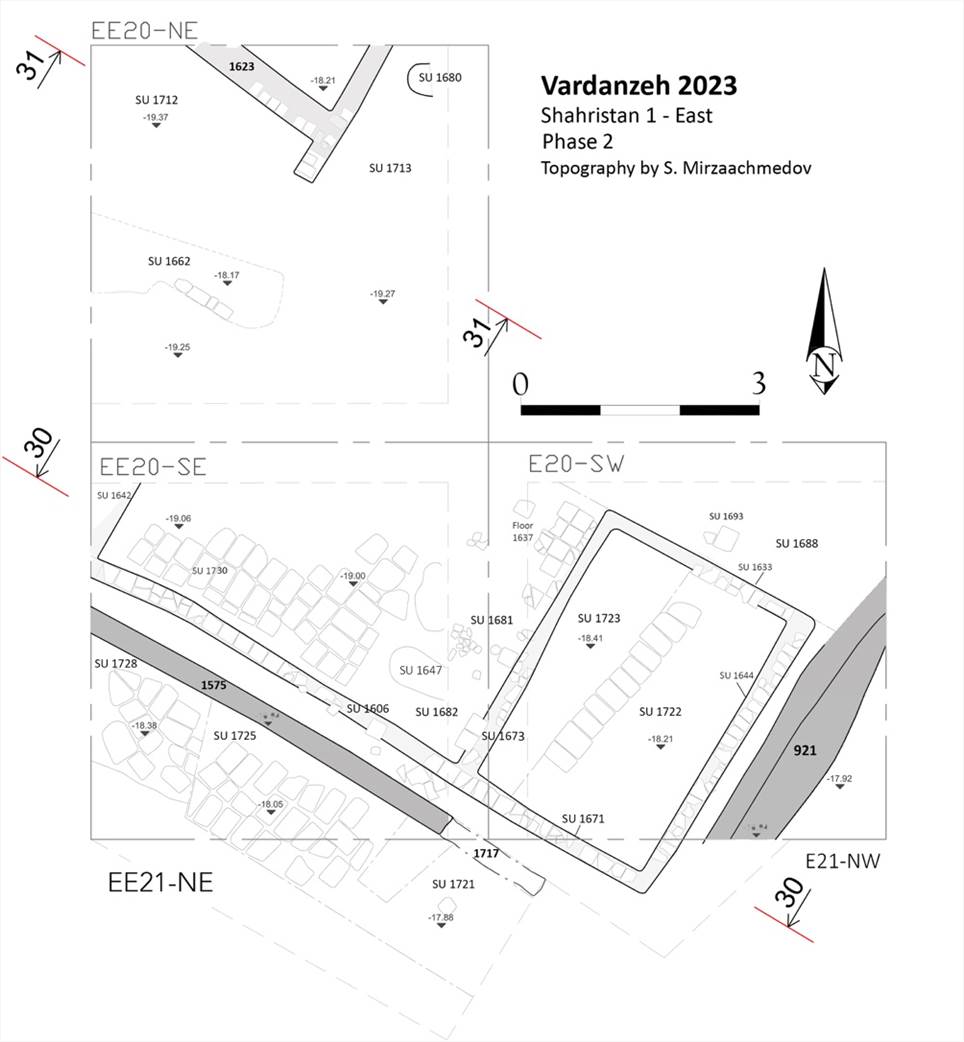

On the Shahristan 1-E, the upper levels were characterized by layers of sandy soil, soil mixed with pebbled and compact layers of clay, walking passage cut by fire place with traces of burnt, charcoal and bones. The upper deposits can be dated from the 16th to the 20th cent. AD.

The southwestern extension of the shahristan E perimeter wall, already exposed in the past years and dated at the late early medieval period, was identified. On its western façade, in a more recent time, a house has been built. Two rooms were exposed up to now (rooms 54 and 55) (Figg. 13-15). The floor of the room 54 was realized using quadrangular backed bricks laid on a foundation made by consistent layers of compact soil alternating with layers of sandy soil mixed with pebbles (technique still in use in the area). On top of those layers, compact layers of clay forming a kind of cortina where the baked bricks were laid and the inner wall of the room were built. An important function of the baked bricks was to isolate the inner house from humidity and keep it warm. This hypothesis was conceived thanks to the analysis of the building techniques employed here: between walls 921 1598 there was an empty space of 15 cm that could be interpreted as a buffer space realized in order to have a good and efficient thermal and acoustic isolation from the outside. Moreover, the wall that delimitated the southern side of room 55 was realized in two different techniques: on east it was used paksha, with several works of reconstruction; on west there were employed mud bricks brick arranged in three rows of stretchers and on top a raw of headers and so on (Fig. 14). This technique has been used from the 4th-5th CE till the 20th century AD, attesting the persistence of this tradition trough the centuries. Finds and pottery found in this level, mostly storage and tableware, can be dated from 19th to 8th-9th century. The removal of this building phase put in light the remains of the early medieval phase, mainly attested by wide mud brick platforms and by the perimeter walls of the shahristan, built in pakhsa. The ancient phase of the perimeter wall of the shahristan consisted in rectangular mud bricks of big dimensions, in use in Sogdiana, Tocharistan e Khorasan until the 5th cent. AD.

In several parts of the trenches, after the removal of very hard layer of clay and paksha, we met a layer of adobe bricks of the big dimensions. All those bricks seem to have been part of a platform, the real use and the purpose of which is still not well ascertained at the actual state of the research. Just the further scientific investigation of this area can give more light on our actual knowledge and clarify the real functions of this feature. We can however say that the platform could be hazardous dated back to at the 5th-cent. AD, if we look at the measurements of the adobe bricks. Pottery related of these layers can be dated around 6th-8th cent. AD, as for example the potsherds of storage jars (khum). In trenches F21-NE and F21-SE we exposed a series of layers of soft and compact clay cut by holes; in a pit, potsherd of the Samanid period have been also found. The rest of the pottery can be dated from 18th to the 9th cent. In the central part of the shahristan 1-E, after the removal of the superficial deposits we found a floor cut by holes, the rectangular one probably used, as happens still nowadays, for storage the vegetables. The pottery found can be dated at the 12th cent and are potsherd of storage and tableware.

To conclude, this first year of extensive excavation in the shahristan seems to evidence that the last occupational level occurred between the late 18th – beginning of the 19th cent. AD. At the present state of the research we can localize the dwelling area mainly along the perimeter walls of the shahristan, while the more inner parts do not show clear and well defined structures but, rather, pits and holes (storage areas functional to the dwelling?). The presence of a two-rooms house, built paying a special attention to the thermic and acoustic insulation, let us to suppose that we are in presence of a stable occupation. The absence of any consistent structures, a part from the house, in the other upper levels of the excavated trenches could eventually suggest the hypothesis that Vardana was organized, at that time, as a village with dwellings built only along the perimeter walls of the shahristan, that represented solid structures that could furnish a barrier for the winds and the sand, with a central area devoid of structures, an empty space or a square welcoming a bazar. The future excavation will clarify if there existed more dwellings and, if so, if they were located, as the one excavated this year, only along the perimeter walls of the shahristan or also in the central area.

The removal of the thick infillings found under the superficial layers didn’t evidence any clear structure yet, but only badly preserved walls. It is thus difficult to say something more about the Medieval occupation of the shahristan, whose presence at the site is however confirmed by the recovery of potsherds dated to the Samanid period. As far as the Early Medieval phase, again is the eastern area of Shahristan 1-E that delivered us more information, as demonstrated by the mud brick and pakhsa platforms. These structures, better preserved in the Shahristan 1-E but unearthed also in the Shahristan 1-W, clearly indicate the original majesty and strength of the shahristan defensive system. Just and only the continuing of the excavation can more knowledge on the evolution and the relations of the architectonical structures in the sequel of the historical events.

Finds

The metal artifacts recovered this year includes 80 bronze coins, 53 iron objects and 8 bronze finds. The coins inventoried as Inv. 898 (Figg. 36-38) in total 77 pieces, were found in an area of ca. 1 m2 and they belong mainly to two main categories: the first is represented by Russian kopecs dating from the end of the 19th to the first decades of the 20th cent. AD and includes coins of 3 kopecs, 2 kopecs 1 kopec and smaller coins (1/2 kopec?). We have also oval and irregular coins that belonged to the Bukharan emirs coinage and two very thin coins.

As far as the iron finds, although of modern dating (late 19th – beg. of the 20th cent. AD), their variety is noteworthy and gives us an idea of the grade of technology in use at Vardanzeh at that time (Figg. 39-41). The majority of the iron finds is represented by tools as knives, mostly fragmented, nails, shovels, hooks, dagger, coal tongs, thimbles, but we found also two buckets, broken during they were unearthed, a teapot a cylindrical box, iron-heels, a doorknob and an oil lamp. Many other registered finds were fragmented and their use is unclear. Interestingly, we also found a weight and two iron slags that would attest some handcraft activity.

The bronze finds unearthed this year include three ornaments, i.e. a bell, part of an earring decoration and a bronze button (Fig. 42). We also found part of an oil lamp and three fragments whose use remains unclear, as well as a rimmed rifle cartridge in use by the Russian Empire.

The glass artifacts (Fig. 45) unearthed this year are few but among them stands a complete pear-shape inkpot, with the inner content still preserved. Made of light greenish glass, the vessel has large neck and ring-shaped rim and it was found on the citadel, inside a rubbish pit dated to the 12th cent. AD. It contained the remains of tissue and herbs, collected for analysis. From the same context comes the bottom part of a glass vessel of turquoise color, probably dated to the same epoch. Another fragment of glass vessel of turquoise color, dated to the 12th cent. AD as well, was unearthed also in the shahristan. More recent (end of 19th – beg. of the 12th cent. AD) are a small essence pot made of uncolored glass and the neck of a small bottle of green color, very encrusted. A bulk of glass past beads of various colors (red, blue, turquoise) was also found.

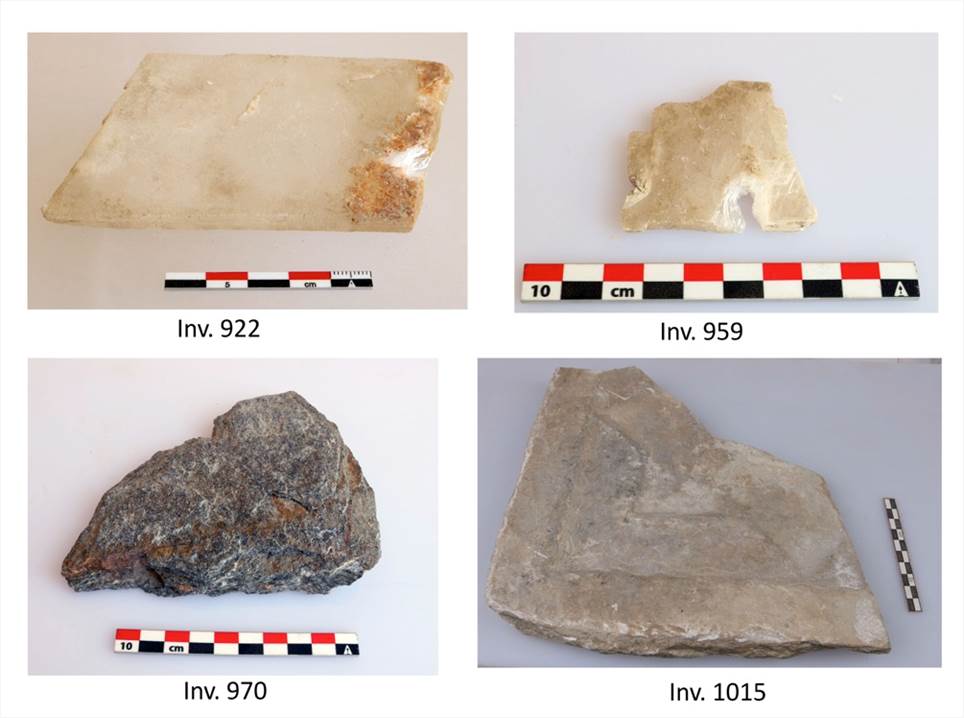

The stone finds (Fig. 43) recovered this year in the trench localized in the citadel consist in two crystal slabs of trapezoidal shape, pierced with a hole, a fragment of millstone in schist, all found inside the medieval hole and thus dated to the 12th cent. AD. From the shahristan it comes a broken marble block, characterized by a carved decoration that seemed to reproduce a star. Most probably this find is a traditional element (in Tajik language daylez) usually positioned inside the houses after the proper entrance, pierced for the drainage of water, still in use until the 20th century.

This year we found several artifacts made of terracotta, both glazed and unglazed (Figg. 44, 46). Among the unglazed finds the zoomorphic toys represent the most interesting category, dated to the late 19th beg. of the 20th cent. AD. The first specimen, probably a horse or a bull, is very badly preserved and only one leg and part of the trunk are still recognizable. The second find, probably a horse, has a quite well preserved trunk and the upper part of the legs is also recognizable. The best-preserved toy functioned also as a whistle: it represents a dog with the muzzle in upper position and a twisted nail. Locally known as hushtak (or khustak), the origins of this kind of toy can be dated back to the Zoroastrian traditions (early medieval period), when the initial use could be that of talismans. A plain whistle was also found. Interesting is also the recovery of a three-armed support used in pottery making for separating the vessels during the heating in the kilns. Among the un-glazed finds there are two terracotta balls and a miniature vessel, pierced on the lateral side, probably used for smoking. Among the finds used in weaving activities we have a small clepsydra-like reel and a spindle whorl probably realized from a potsherd and dated back to the 7th-8th cent. AD. The glazed terracotta finds include some oil lamps (chirag). The first is a fragment of an unusual oil lamp decorated with whitish glazing: still preserved only the dish-like base and the central foot that should have supported the upper lamp. We found also three oil lamps with a circular oil-tank, covered by greenish glazing, similar to the specimens found very often in the past years.

The excavation of the superficial and relatively recent (late 19th beg. of the 20th cent. AD) deposits localized in the shahristan allowed us to find several examples of organic materials that usually are difficult to discover. Most of this kind of finds was unearthed in the E trenches, more precisely in the rooms along the inner side of the E perimeter wall of the shahristan. Among the several fragments of cotton clothes we were able to isolate two well-preserved traditional hats (arak chin) (Fig. 46). Judging from the size, they probably belonged to young persons. The first specimen was made by enrolled woven elements of light green color, radially positioned, and had an inner lining decorated with a colorful pattern, white and pink. The second, better preserved, was realized exactly in the same way but the green color was slightly more marked. Several fragments of leather shoes were also recovered and one of them was inventoried: this is the point of a leather shoe of black color, very big, that probably belonged to a male. Of great interest is also the finial of a traditional Uzbek crib (beshik). Cone shaped, the finial measured 12 cm in length and was found completely burned on the floor of the room along the perimeter wall. Still visible the horizontal carved bands that decorated the surface. The last two finds that deserve a mention are a dome-shaped object, possibly a sort of large spindle whorl used for weaving activities, realized with a bone, a small cylindrical bead made in coral and a very small cowry shell .

INTRODUCTION

The twelfth archaeological expedition at Vardanzeh was realized between August, 19, and September, 20, plus other full 4 days devoted to complete the graphic and photographic documentation, as well as to the pottery database. The activity focused on the lower city (shahristan) located to the south from the citadel. At Vardanzeh the shahristan is formed by two distinct areas, one of quadrangular shape, located to the south from the citadel and separated from it by a deep moat, and a second area that spreads irregularly to the south from the previous one. We conventionally labeled these two areas shahristan 1 (the northern one) and shahristan 2 (the southern one). This year the shahristan 1 was investigated extensively, opening trenches both to the west and to the east from the street that runs trough the whole shahristan and ends to the citadel (Fig. 1). This street, detached from the main road located southwards, is modern but it is not excluded it overlapped an older one. The area to the west of the street was labeled ‘Shahristan 1-West’ and the one to the east ‘Shahristan 1-East’, in order to facilitate the localization of the excavated squares.

Following the topographic grid system we opened 9 squares in the Shahristan-1 West and 7 squares in the Shahristan-1 East (Fig. 2). Each square measured 5x5 m, for a total surface of 400 m2, with adjoining squares separated each other by balks 1 m wide. A localized excavation interested the citadel as well: we opened an area of ca. 9 m2 in the eastern part of the citadel.

This year research staff was composed of five archaeologists: Silvia Pozzi, Ilaria Vincenzi and Dzamal K. Mirzaachmedov in quality of senior archaeologists. Two PhD students, Orifhoja Muminov and Nishonboy Qulboyev, from the National Center of Archaeology of Academy of Science of the Republic of Uzbekistan based in Tashkent, took part to the excavation in quality of junior archaeologists. Siroj Mirzaachmedov, architect from the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand, was in charge of the topographic documentation, using also photogrammetry techniques for a better representation of the excavated structures. This year we introduced 3D Lidar technology using Polycam application available for free in Ipad Pro. This instrument allowed us to make measurable 3D reliefs of the stratigraphic units and structures. A daily documentation trough this tool has revealed a valid support in addition to the more traditional documenting techniques.

Munira Sultanova, architect and conservator also working at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand, drew a selection of artefacts, among pottery and small finds. The conservator, Dilmurod Kholov, was in charge of the cleaning and the conservation of metal artefacts unearthed this year.

Activites and results

On the citadel, the activities carried on the eastern area put in light the late antique structures buried under meters of pebbles and sand deposits. Two underground galleries labeled Gallery A and Gallery B with Corridor N and Corridor S to it connected; remains of the roof of the gallery A made in three-four layers of mud bricks put in horizontally (Figg 4-6). The underground system of galleries should have been connected to rooms and halls and traces of similar features were already detected in the past years in other parts of the citadel, attesting the existence of a net of galleries probably connected with the eastern gate of the citadel. It is not excluded that the eastern gate could have represented, at a given moment, the main entrance of the citadel, without excluding the existence of more upper passages/exits leading to the Early Medieval Palace.

The lower city has been investigates extensively, both in its western and eastern sides. It was ascertained that the most recent traces of a stable occupation are dated to the late 19th – beginning of the 20th cent. AD, as attested by the recovery of several glazed and unglazed pottery finds dated to this period, as well as a large quantity of iron fragments (tools, buckets), oil lamps, shoes, traditional Uzbek hats made of cotton, terracotta toys and many other finds.

On Shahristan 1-West the pottery found in the lower phases can be dated at the Early Medieval Period and consisted mostly in potsherd of storage and tableware ware. All trenches, in their upper layers, are characterized by series of deposits of compact clay and soft soils with traces of burning, charcoal, kilns, drainage systems and a lot of ceramics dated late 19th - early 20th cent (Figg. 7-12). A interesting bulk of 72 bronze coins, mainly formed by Russian kopeks and Bukhara late emir coins was found at this level, directly on a floor and close to the remains of a tree and to two glazed cups (Fig. 6). This feature would suggest that this area could have been a sort of holy place where locals left small coins as devotional offerings. Instead, the lower layers were very compact and hard to excavate: these features, that we cannot still label platform, let us assume that their function could have been that of sealing the previous phases (i.e. the EMP) of the life of the shahristan.

On the Shahristan 1-E, the upper levels were characterized by layers of sandy soil, soil mixed with pebbled and compact layers of clay, walking passage cut by fire place with traces of burnt, charcoal and bones. The upper deposits can be dated from the 16th to the 20th cent. AD.

The southwestern extension of the shahristan E perimeter wall, already exposed in the past years and dated at the late early medieval period, was identified. On its western façade, in a more recent time, a house has been built. Two rooms were exposed up to now (rooms 54 and 55) (Figg. 13-15). The floor of the room 54 was realized using quadrangular backed bricks laid on a foundation made by consistent layers of compact soil alternating with layers of sandy soil mixed with pebbles (technique still in use in the area). On top of those layers, compact layers of clay forming a kind of cortina where the baked bricks were laid and the inner wall of the room were built. An important function of the baked bricks was to isolate the inner house from humidity and keep it warm. This hypothesis was conceived thanks to the analysis of the building techniques employed here: between walls 921 1598 there was an empty space of 15 cm that could be interpreted as a buffer space realized in order to have a good and efficient thermal and acoustic isolation from the outside. Moreover, the wall that delimitated the southern side of room 55 was realized in two different techniques: on east it was used paksha, with several works of reconstruction; on west there were employed mud bricks brick arranged in three rows of stretchers and on top a raw of headers and so on (Fig. 14). This technique has been used from the 4th-5th CE till the 20th century AD, attesting the persistence of this tradition trough the centuries. Finds and pottery found in this level, mostly storage and tableware, can be dated from 19th to 8th-9th century. The removal of this building phase put in light the remains of the early medieval phase, mainly attested by wide mud brick platforms and by the perimeter walls of the shahristan, built in pakhsa. The ancient phase of the perimeter wall of the shahristan consisted in rectangular mud bricks of big dimensions, in use in Sogdiana, Tocharistan e Khorasan until the 5th cent. AD.

In several parts of the trenches, after the removal of very hard layer of clay and paksha, we met a layer of adobe bricks of the big dimensions. All those bricks seem to have been part of a platform, the real use and the purpose of which is still not well ascertained at the actual state of the research. Just the further scientific investigation of this area can give more light on our actual knowledge and clarify the real functions of this feature. We can however say that the platform could be hazardous dated back to at the 5th-cent. AD, if we look at the measurements of the adobe bricks. Pottery related of these layers can be dated around 6th-8th cent. AD, as for example the potsherds of storage jars (khum). In trenches F21-NE and F21-SE we exposed a series of layers of soft and compact clay cut by holes; in a pit, potsherd of the Samanid period have been also found. The rest of the pottery can be dated from 18th to the 9th cent. In the central part of the shahristan 1-E, after the removal of the superficial deposits we found a floor cut by holes, the rectangular one probably used, as happens still nowadays, for storage the vegetables. The pottery found can be dated at the 12th cent and are potsherd of storage and tableware.

To conclude, this first year of extensive excavation in the shahristan seems to evidence that the last occupational level occurred between the late 18th – beginning of the 19th cent. AD. At the present state of the research we can localize the dwelling area mainly along the perimeter walls of the shahristan, while the more inner parts do not show clear and well defined structures but, rather, pits and holes (storage areas functional to the dwelling?). The presence of a two-rooms house, built paying a special attention to the thermic and acoustic insulation, let us to suppose that we are in presence of a stable occupation. The absence of any consistent structures, a part from the house, in the other upper levels of the excavated trenches could eventually suggest the hypothesis that Vardana was organized, at that time, as a village with dwellings built only along the perimeter walls of the shahristan, that represented solid structures that could furnish a barrier for the winds and the sand, with a central area devoid of structures, an empty space or a square welcoming a bazar. The future excavation will clarify if there existed more dwellings and, if so, if they were located, as the one excavated this year, only along the perimeter walls of the shahristan or also in the central area.

The removal of the thick infillings found under the superficial layers didn’t evidence any clear structure yet, but only badly preserved walls. It is thus difficult to say something more about the Medieval occupation of the shahristan, whose presence at the site is however confirmed by the recovery of potsherds dated to the Samanid period. As far as the Early Medieval phase, again is the eastern area of Shahristan 1-E that delivered us more information, as demonstrated by the mud brick and pakhsa platforms. These structures, better preserved in the Shahristan 1-E but unearthed also in the Shahristan 1-W, clearly indicate the original majesty and strength of the shahristan defensive system. Just and only the continuing of the excavation can more knowledge on the evolution and the relations of the architectonical structures in the sequel of the historical events.

Finds

The metal artifacts recovered this year includes 80 bronze coins, 53 iron objects and 8 bronze finds. The coins inventoried as Inv. 898 (Figg. 36-38) in total 77 pieces, were found in an area of ca. 1 m2 and they belong mainly to two main categories: the first is represented by Russian kopecs dating from the end of the 19th to the first decades of the 20th cent. AD and includes coins of 3 kopecs, 2 kopecs 1 kopec and smaller coins (1/2 kopec?). We have also oval and irregular coins that belonged to the Bukharan emirs coinage and two very thin coins.

As far as the iron finds, although of modern dating (late 19th – beg. of the 20th cent. AD), their variety is noteworthy and gives us an idea of the grade of technology in use at Vardanzeh at that time (Figg. 39-41). The majority of the iron finds is represented by tools as knives, mostly fragmented, nails, shovels, hooks, dagger, coal tongs, thimbles, but we found also two buckets, broken during they were unearthed, a teapot a cylindrical box, iron-heels, a doorknob and an oil lamp. Many other registered finds were fragmented and their use is unclear. Interestingly, we also found a weight and two iron slags that would attest some handcraft activity.

The bronze finds unearthed this year include three ornaments, i.e. a bell, part of an earring decoration and a bronze button (Fig. 42). We also found part of an oil lamp and three fragments whose use remains unclear, as well as a rimmed rifle cartridge in use by the Russian Empire.

The glass artifacts (Fig. 45) unearthed this year are few but among them stands a complete pear-shape inkpot, with the inner content still preserved. Made of light greenish glass, the vessel has large neck and ring-shaped rim and it was found on the citadel, inside a rubbish pit dated to the 12th cent. AD. It contained the remains of tissue and herbs, collected for analysis. From the same context comes the bottom part of a glass vessel of turquoise color, probably dated to the same epoch. Another fragment of glass vessel of turquoise color, dated to the 12th cent. AD as well, was unearthed also in the shahristan. More recent (end of 19th – beg. of the 12th cent. AD) are a small essence pot made of uncolored glass and the neck of a small bottle of green color, very encrusted. A bulk of glass past beads of various colors (red, blue, turquoise) was also found.

The stone finds (Fig. 43) recovered this year in the trench localized in the citadel consist in two crystal slabs of trapezoidal shape, pierced with a hole, a fragment of millstone in schist, all found inside the medieval hole and thus dated to the 12th cent. AD. From the shahristan it comes a broken marble block, characterized by a carved decoration that seemed to reproduce a star. Most probably this find is a traditional element (in Tajik language daylez) usually positioned inside the houses after the proper entrance, pierced for the drainage of water, still in use until the 20th century.

This year we found several artifacts made of terracotta, both glazed and unglazed (Figg. 44, 46). Among the unglazed finds the zoomorphic toys represent the most interesting category, dated to the late 19th beg. of the 20th cent. AD. The first specimen, probably a horse or a bull, is very badly preserved and only one leg and part of the trunk are still recognizable. The second find, probably a horse, has a quite well preserved trunk and the upper part of the legs is also recognizable. The best-preserved toy functioned also as a whistle: it represents a dog with the muzzle in upper position and a twisted nail. Locally known as hushtak (or khustak), the origins of this kind of toy can be dated back to the Zoroastrian traditions (early medieval period), when the initial use could be that of talismans. A plain whistle was also found. Interesting is also the recovery of a three-armed support used in pottery making for separating the vessels during the heating in the kilns. Among the un-glazed finds there are two terracotta balls and a miniature vessel, pierced on the lateral side, probably used for smoking. Among the finds used in weaving activities we have a small clepsydra-like reel and a spindle whorl probably realized from a potsherd and dated back to the 7th-8th cent. AD. The glazed terracotta finds include some oil lamps (chirag). The first is a fragment of an unusual oil lamp decorated with whitish glazing: still preserved only the dish-like base and the central foot that should have supported the upper lamp. We found also three oil lamps with a circular oil-tank, covered by greenish glazing, similar to the specimens found very often in the past years.

The excavation of the superficial and relatively recent (late 19th beg. of the 20th cent. AD) deposits localized in the shahristan allowed us to find several examples of organic materials that usually are difficult to discover. Most of this kind of finds was unearthed in the E trenches, more precisely in the rooms along the inner side of the E perimeter wall of the shahristan. Among the several fragments of cotton clothes we were able to isolate two well-preserved traditional hats (arak chin) (Fig. 46). Judging from the size, they probably belonged to young persons. The first specimen was made by enrolled woven elements of light green color, radially positioned, and had an inner lining decorated with a colorful pattern, white and pink. The second, better preserved, was realized exactly in the same way but the green color was slightly more marked. Several fragments of leather shoes were also recovered and one of them was inventoried: this is the point of a leather shoe of black color, very big, that probably belonged to a male. Of great interest is also the finial of a traditional Uzbek crib (beshik). Cone shaped, the finial measured 12 cm in length and was found completely burned on the floor of the room along the perimeter wall. Still visible the horizontal carved bands that decorated the surface. The last two finds that deserve a mention are a dome-shaped object, possibly a sort of large spindle whorl used for weaving activities, realized with a bone, a small cylindrical bead made in coral and a very small cowry shell .

Fig. 1 Satellite photo of Vardanzeh archaeological area: in green modern road external to the site, in red modern road crossing the site (Courtesy of The Digital Globe Foundation).

Fig. 2 Citadel, general plan of the 2023 excavated squares (topography by Mirzaachmedov on Cerasuolo relief).

Fig. 3 Shahristan 1-E, Lower levels plans (topography by S. Mirzaachmedov).

Fig. 4 Citadel,: Voids on the W and E sections of the trench, view from S.

Fig. 5 Citadel: Gallery B, particular of wall 1516.

Fig. 6 Shahristan 1-W, trench I13-NW: Bulk of coins on floor 1480 (view from N).

Fig. 7 Shahristan 1-W, trench I13-NW: Drainage system SU 1479 and mud brick structure SU 1484 (view from E).

Fig. 8 Shahristan 1-W, trench II13-NE: Wall 1518; fireplaces SSUU 1519,1523; rammed floor SU 1536; layer of soft soil with potsherds SU1534 (view from N).

Fig. 9 Shahristan 1-W, general view of the final situation in trenches I13-NW, I13-SW, II13-NE, II13-SE (Polycam).

Fig. 10 Shahristan 1-W, trenches J13-SW, J13-SE, II13-SW: Mud brick floor SU 1551 and platform 1526 (Polycam).

Fig. 11 Shahristan 1-W, trenches J13-SW, J13-SE, II13-SW: Wall 1550 (view from NW) (Polycam).

Fig. 12 Shahristan 1-W, trench K16-SE: Final situation (Polycam).

Fig. 13 Rammed floor SU 1679, baked brick floor 1679, SU1681; 1682 (view from N).

Fig. 14 General view of the trench and of the infillings under room 55 (view from NE).

Fig. 15 Progressive phases of excavation (Polycam).

Fig. 16 Final situation (Polycam).

Fig. 17 Final situation (view from E).

Fig. 18 Bases of bowls, pierced in the central part (1488-1; 1488-2), rim of dishes (1487-7; 1487-8; 1488-12, 1488-13); walls of glazed vessels (1488-6; 1488-11; 1488-14).

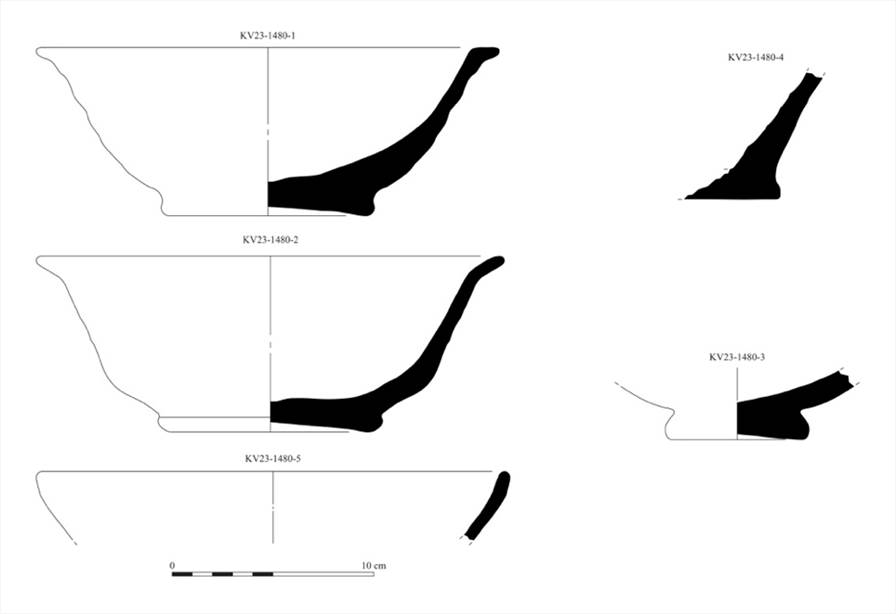

Fig. 19 Archaeologically complete plates (1480-1, 1480-2); base of jar? (1480-4); base of a plate (1480-3); rim of a plate (1480-5).

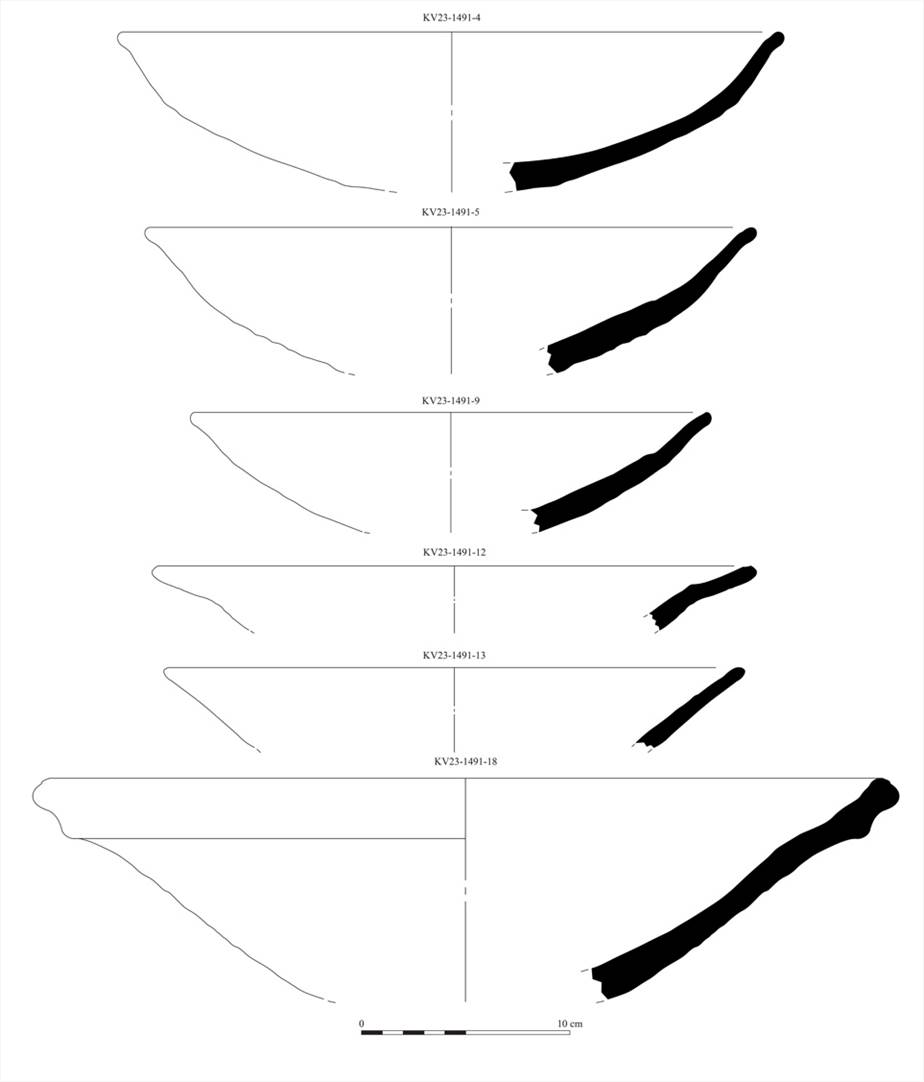

Fig. 20 Base of a basin (1491-1); base of a jug (1491-2); rim of a a glazed dish (1491-3); rim of a glazed dish with an inciced geometrical decoration of black colour (1491-4); rim of a glazed yellow and brownglazed dish (1491-5); base of a glazed yellow plate with a a green decoration (1491-6; rim of a glazed green plate (1491-7); base of a glazed yellow plate with a brow green decoration inside (1491-8); base of a green glazed dish with a geometrical incised decoration (1491-9); base of a glazed dish (1491-13); base of a yellow glazed dish (1491-15); base of a black glazed jar (1491-16); tourqoise glazed handle of a jug (1491-10).

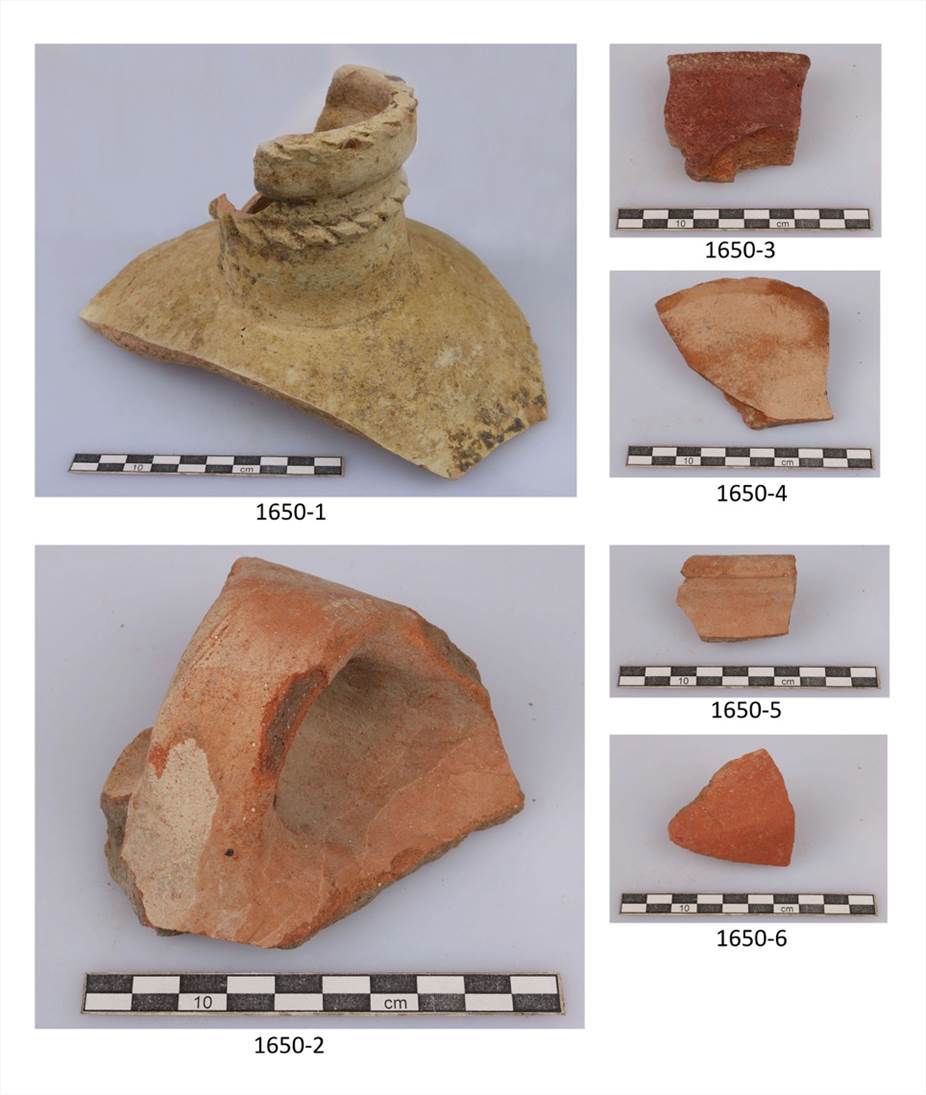

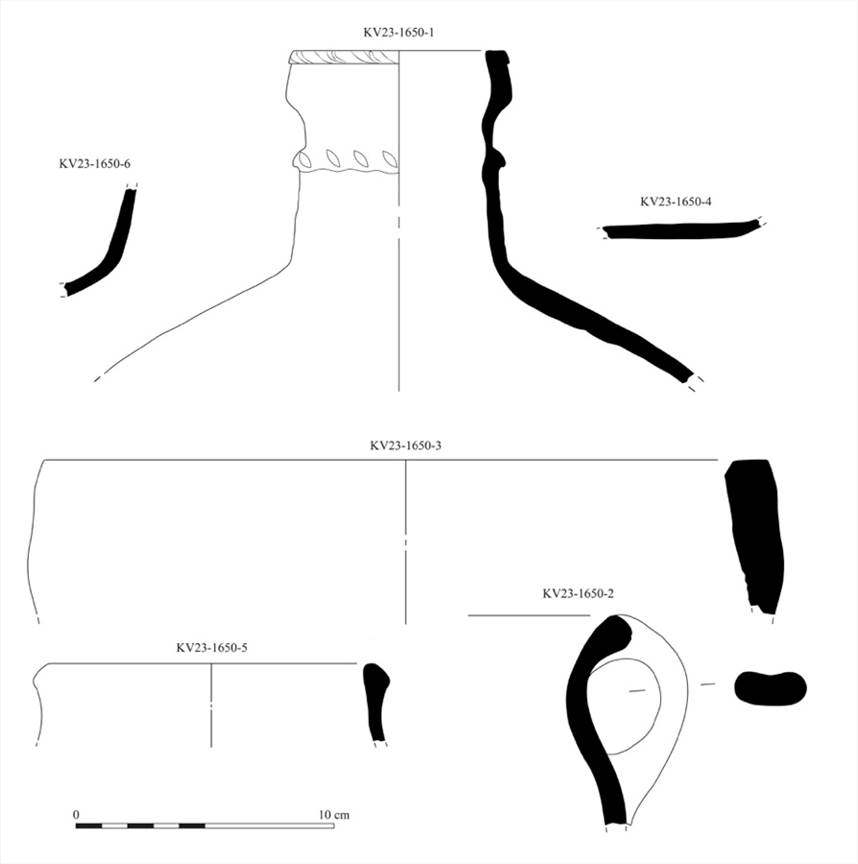

Fig. 21 Rim and shoulder of a Jug (1650-1), rim of a jug (1650-3) base of a pot (1650-4); handle of an ollae (1650-2); rim of a jug (1650-5); wall of a jug (1650-6).

Fig. 22 Rim of a glazed dish with a green brown decoration (1570-6); base of a glazed green dish with incised decoration (1578-8); base and wall of a glazed green bowl (1670-9); Jug with an incised decoration on the shoulder (1570-1); wall of an ovoid jug (1570-7); handle of a jug (1570-11); lid of a bottle (1570-10); cup in porcelaine (1570-4) cup in porcelaine (1570-5); glazed yellowish bowl (1570-3); glazed brown-green dish (1570-2).

Fig. 23 Base of a glazed yellow-green bowl with a brow-dark decoration (1571-1); glazed green jug (1571-2); glazed green cup (1571-3).

Fig. 24 Rim of a glazed white bowl with a brown and red decoration (1715-1); base of a glazed bowl (1715-2); wall of a bowl (1715-3).

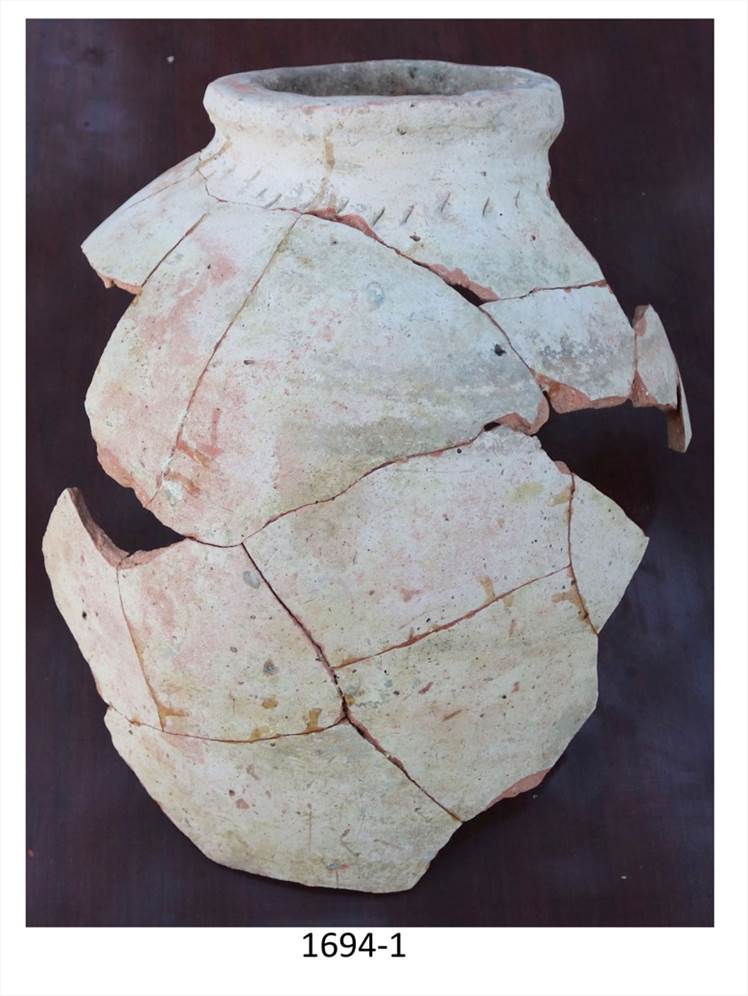

Fig. 25 Medieval jar (1694-1).

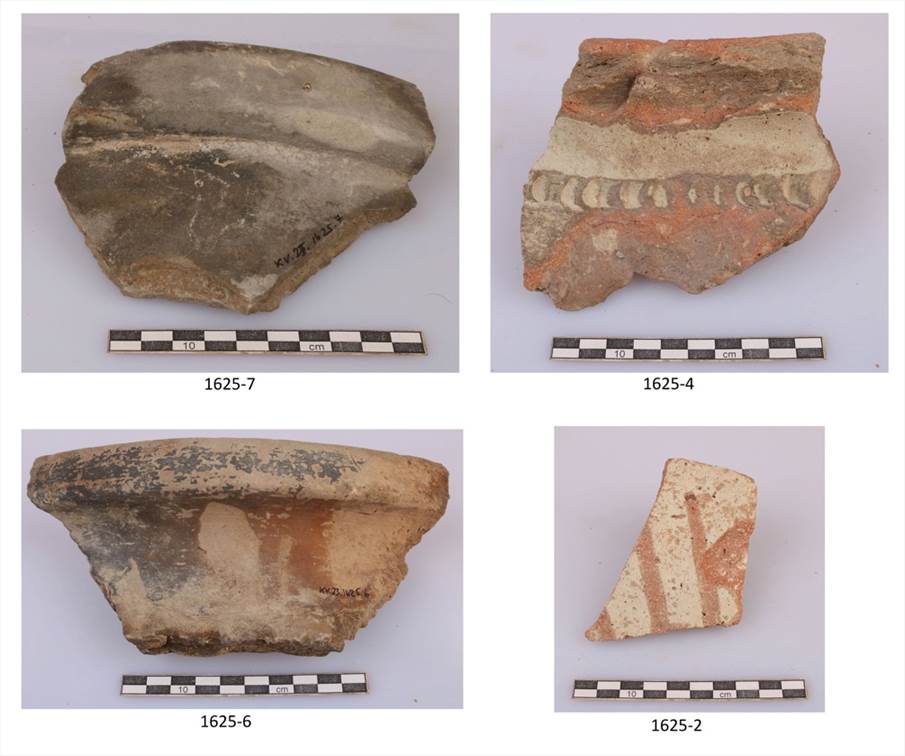

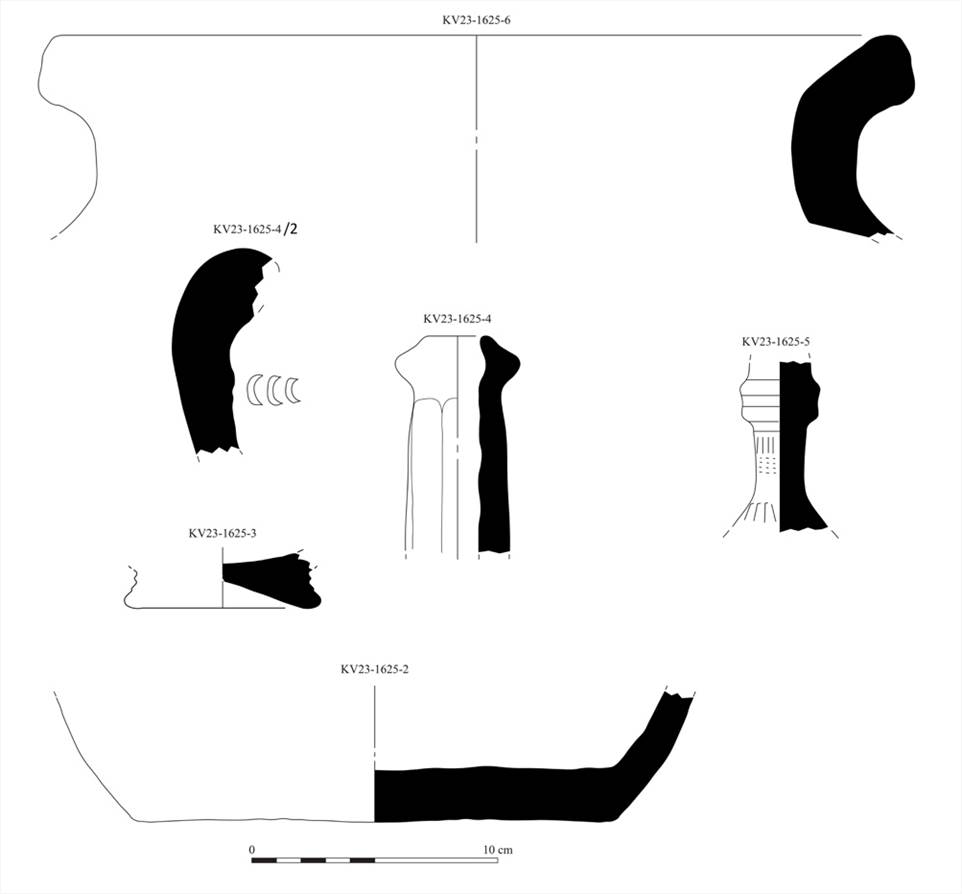

Fig. 26 Rim of a jar (1625-7); rim of a jar decorated with fingermarks (1625-4); rim of a basin (1625-6); decorated wall of a jar (1625-2).

Fig. 27 Glazed plate (1696-1); rim of jar (1696-2).

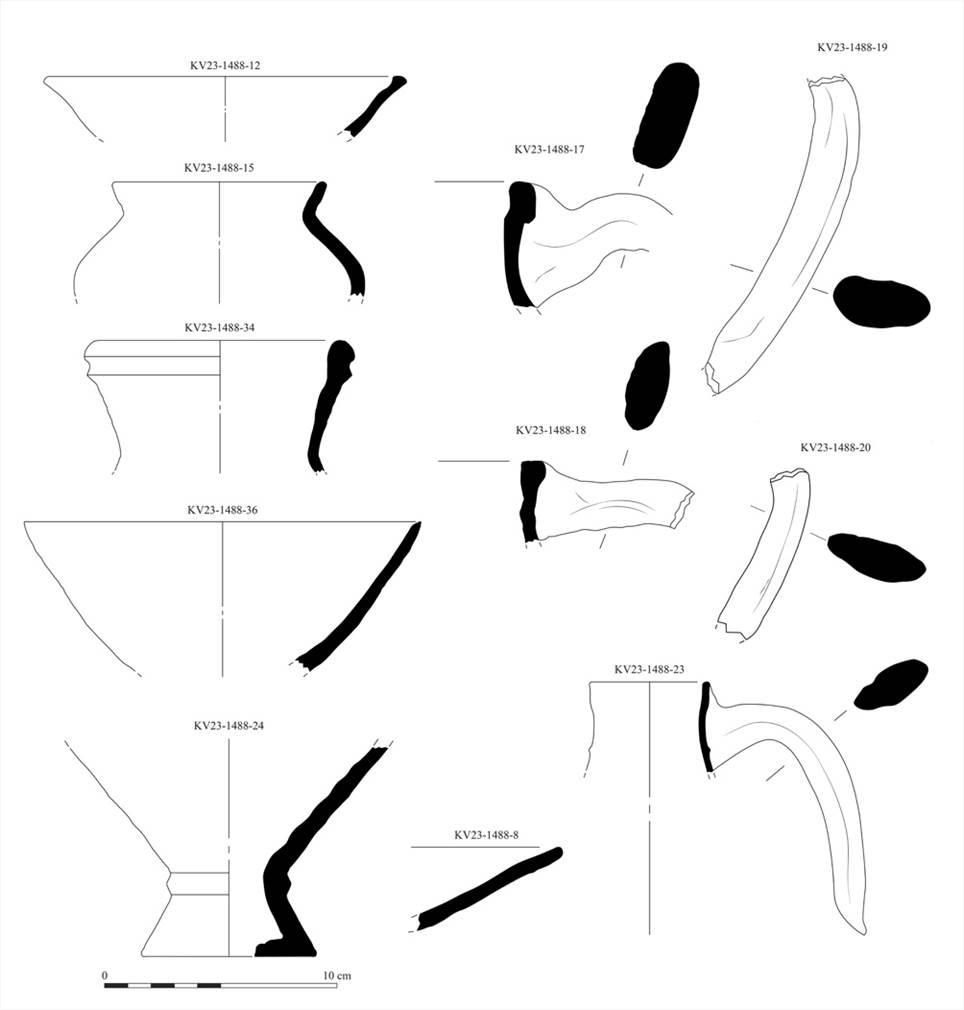

Fig. 28 Unglazed ware: 1488-15, 1488-34, 1488-24, 1488-17, 1488-18, 1488-19, 1488-20, 1488-23; glazed ware: 1488-12, 1488-36, 1488-8 (drawings by M. Sultanova).

Fig. 29 Glazed ware: 1480-1,1480-2; 1480-3, 1480-5; unglazed ware: 1480-4(drawings by M. Sultanova).

Fig. 30 Glazed ware (drawings by M. Sultanova).

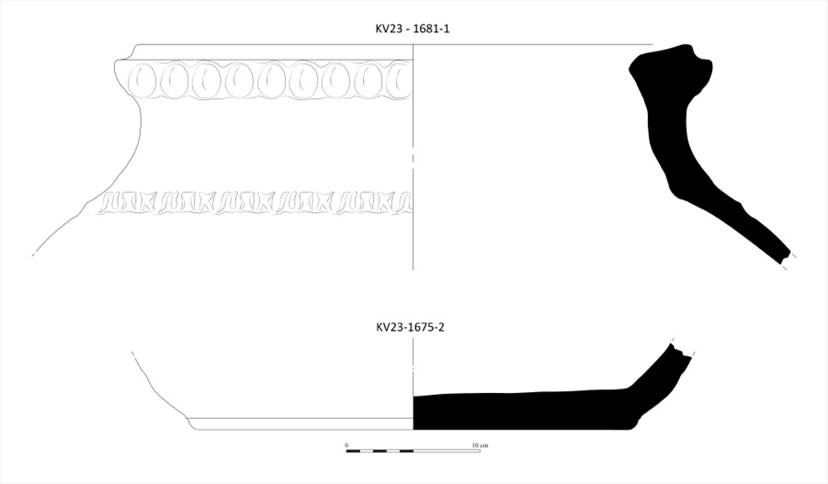

Fig. 31 Unglazed ware: 1681-1; glazed ware: 1675-2 (drawings by M. Sultanova).

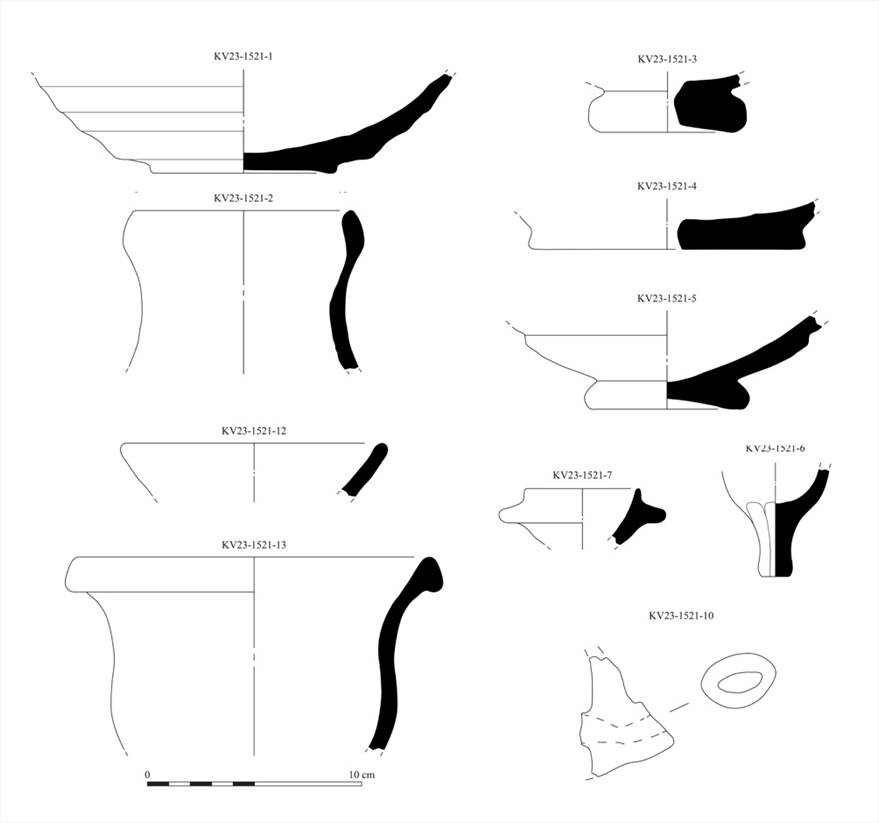

Fig. 32 Glazed ware: 1521-1, 1521-2, 1521-3, 1521-4, 1521-5, 1521-6, 1521-7, 1521-12, 1521-13; Unglazed ware: 1521-10 (drawings by M. Sultanova).

Fig. 33 Unglazed jug with decoration incised on the shoulder (drawings by M. Sultanova).

Fig. 126 Unglazed ware (drawings by M. Sultanova).

Fig. 35 Glazed ware; 1625-2, 1625-3; unglazed ware: 1625-4, 1625.5, 1625-6 (drawings by M. Sultanova).

Fig. 36 Small treasure of bronze coins (Inv. 898): oval and irregular coins of Bukharan 18th-19th cent. emirs (obverse).

Fig. 37 Small treasure of bronze coins (Inv. 898): oval and irregular coins of Bukharan 18th-19th cent. emirs (reverse).

Fig. 38 Small treasure of bronze coins (Inv. 898): Russian Kopecs (obverse and reverse).

Fig. 39 Iron finds: nails (Inv. 974, 979, 1007, 1003, 1010); doorknob (Inv. 984); dagger (Inv. 1012); door handle (Inv. 995); shovel (Inv. 991, 992); hook (Inv. 993); handle of a bucket (Inv. 997).

Fig. 40 Iron Finds: teapot (Inv. 902); cylindrical box (Inv. 905); shovel (Inv. 933); iron slags (Inv. 911); unknown objects (Inv. 930, 946, 947); knives (Inv. 900, 929, 942); part of a dish? (Inv. 908); fragment of a shovel (Inv. 971); iron rod (Inv. 967); fragment of an handle (Inv. 961); tongs for coals (Inv. 907).

Fig. 41 Iron finds: hook (Inv. 921); fragment of a tubular object (Inv. 932); handle (Inv. 939); thimbles (Inv. 935, 938); horseshoes/iron-heels? (Inv. 964, 927, 906); Bronze finds: bell (Inv. 901); oil lamp (Inv. 909).

Fig. 42 Bronze finds: cylindrical object of unknow use (Inv. 1004); rifle cartridge in use by the Russian Empire (Inv. 914); broken illegible coin (Inv. 983); illegible coin (Inv. 975); tubular pointed object of unknown use (Inv.976); botton (Inv. 994).

Fig. 43 Stone finds: crystal slabs (Inv. 922, 959); black stone (Inv. 970); broken decorated marble block (Inv. 1015).

Fig. 44 Terracotta finds: ball (Inv. 904); fragment of a zoomorphic toys (Inv. 960, 973, 999); three-armed support (Inv. 962); glazed oil lamp (Inv. 969; clepsydra-like reel (Inv. 985); miniature vessel, pipe? (Inv. 986); whistle (Inv. 988); ball (Inv. 1000); spindle whorl (Inv. 1011).

Fig. 45 Glass finds: pear-shaped ink pot (Inv.903); fragment of the bottom part of a bottle (Inv. 923); fragment of a bottom part of glass bottle (Inv. 1013); essence pot (Inv. 980); neck of a small bottle (Inv. 1014); red, blue, tourquoise beads (Inv. 1006).

Fig. 46 Terracotta finds: Glazed oil lamp (Inv. 987, 989, 1008); neckless bead (Inv. 996). Organic finds: part of a leather shoe (Inv. 944); bone-dome shaped object pierced in the middle (Inv. 972) traditional cotton hats (Inv. 977, 1009); wooden crib (beshik) (Inv. 981); iron weight (Inv. 918); little shell pierced in the middle used as a necklace bead (Inv. 1002); piece of iron unknown use (Inv. 913).

Fig. 47 Workes employed in the field work.

Fig. 48 Workes and archaeologists.

Fig. 49 Workes and archaeologists in the trenches excavated in Shahristan 1-East.

Fig. 50 Team involved in Vardanzeh excavation togheter with Dr. Chirstoph Baumer and Therese Weber visiting the site (the Society for the Exploration of EurAsia).

| copyright by The Society for the Exploration of EurAsia| E-mail | Home | ![]()