Eurasia Exploration Society, Switzerland International Institute for Central Asian Studies Archaeological Expertise LLP, Kazakhstan

FIELD REPORT ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS AT USHARAL-ILIBALYK, KAZAKHSTAN IN 2020

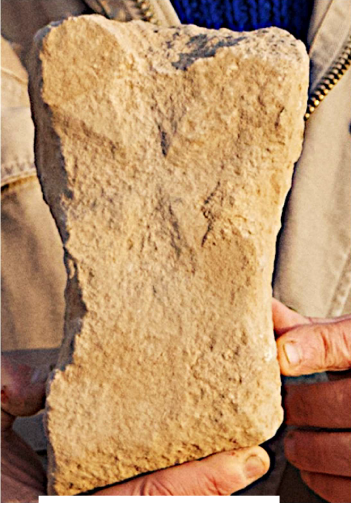

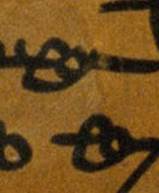

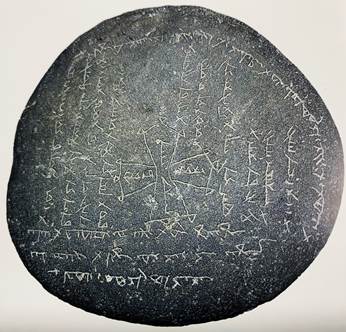

Gravestone found at Usharal-Ilibalyk in 2020 at cemetery with Syriac inscription

Almaty 2020

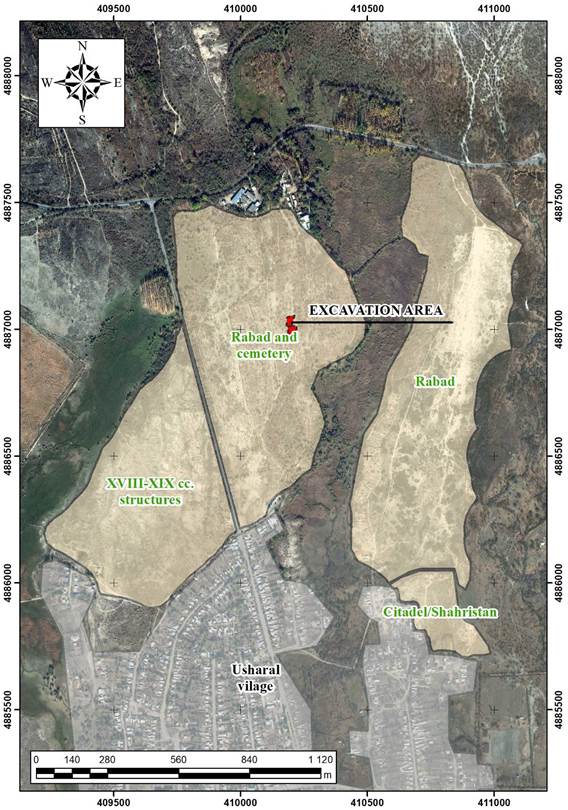

The object of archaeological research for this excavation in 2020 was the cemetery of the Ilibalyk settlement, located in the Panfilov district of the Almaty oblast on the northern outskirts of the village of Usharal, Republic of Kazakhstan.

Purpose of the work:

Research was conducted on the site of the western rabad (suburban district) in order to obtain additional data on the cemetery and to identify new cultural material related to the Christian community of the medieval city of Ilibalyk.

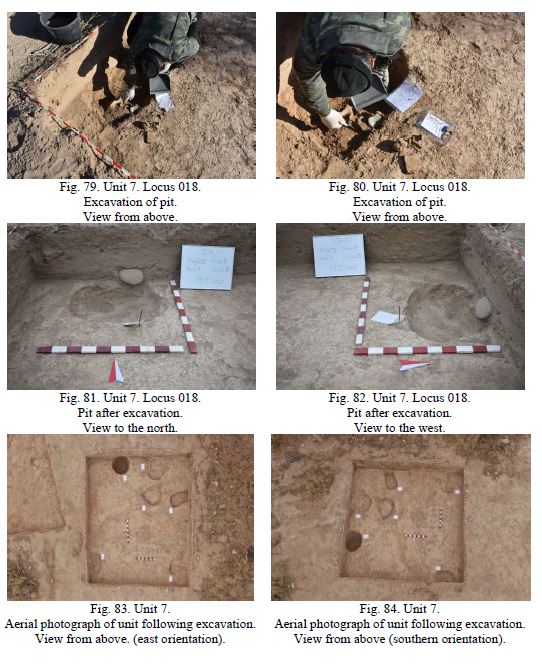

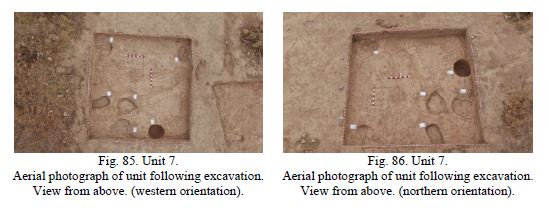

Goals:

-

To determine the limits of the cemetery to the south and east of the identified boundaries as revealed during the 2019 excavation.

-

To identify potential architectural features in Field IV (the western part of the rabad

(suburban district)) related to the cemetery.

-

To identify the revealed details of the archaeological excavation and study the stratigraphy.

-

To conduct aerial photography, a tacheometric survey, and photogrammetry.

-

To conduct soil samples for natural science analysis and archaeological flotation.

-

To identify all the revealed details of the archaeological excavation by means of aerial photography, microtopography, tacheometric survey, and photographic recording.

-

To provide laboratory processing of the cultural materials and a graphic presentation of the results.

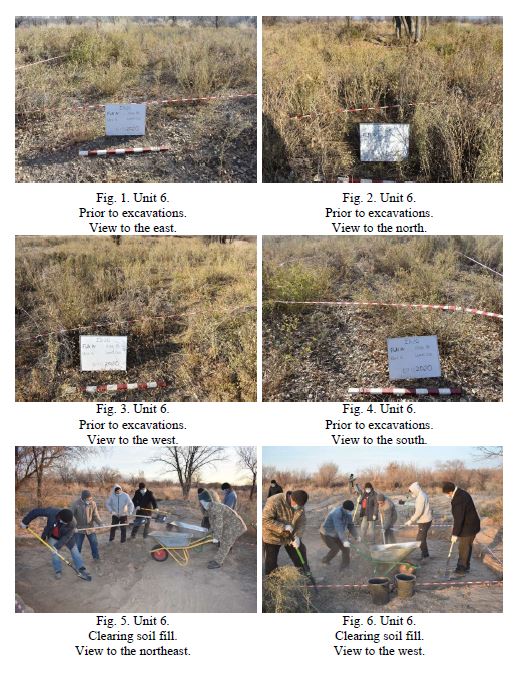

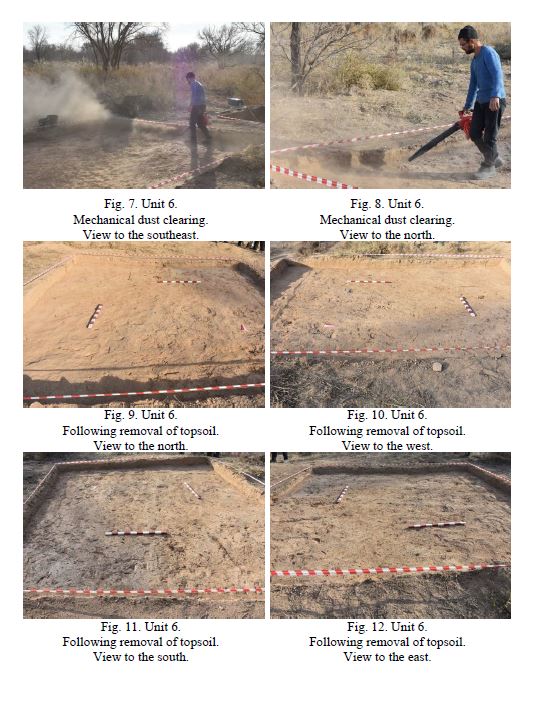

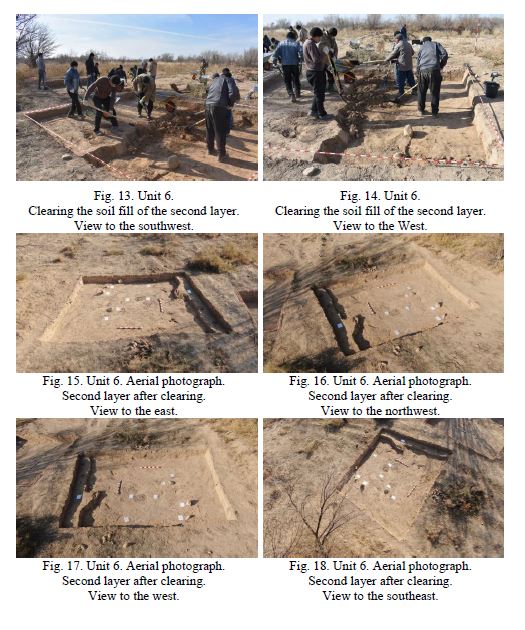

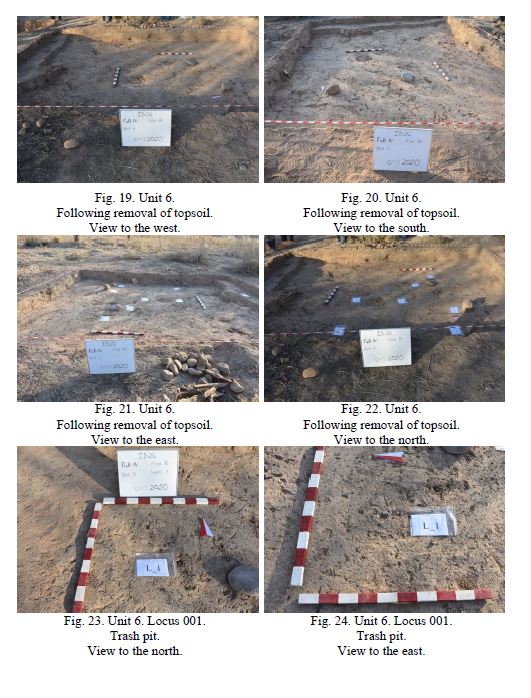

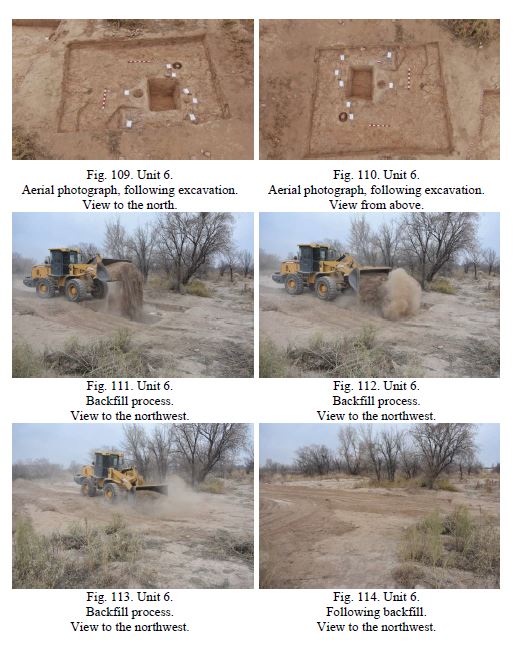

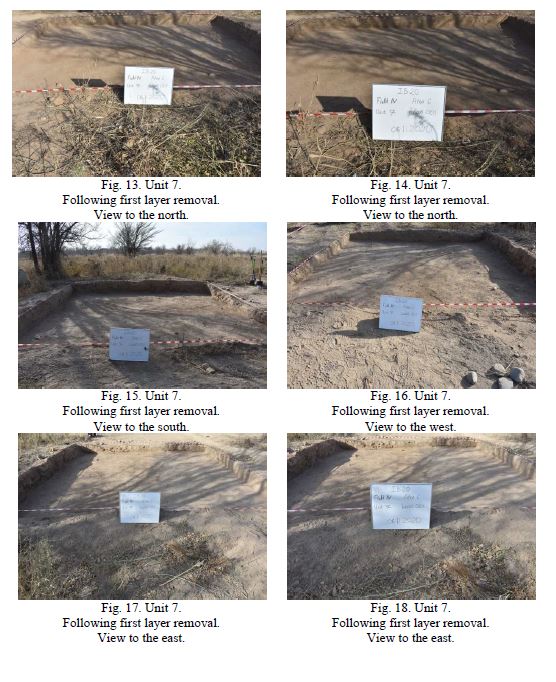

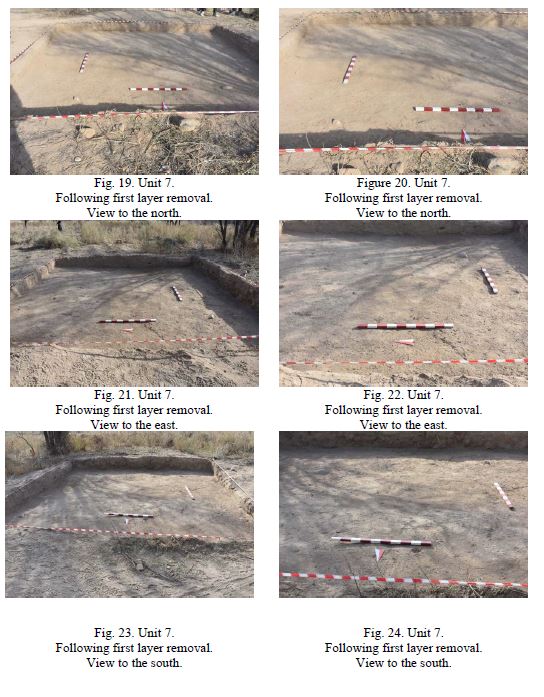

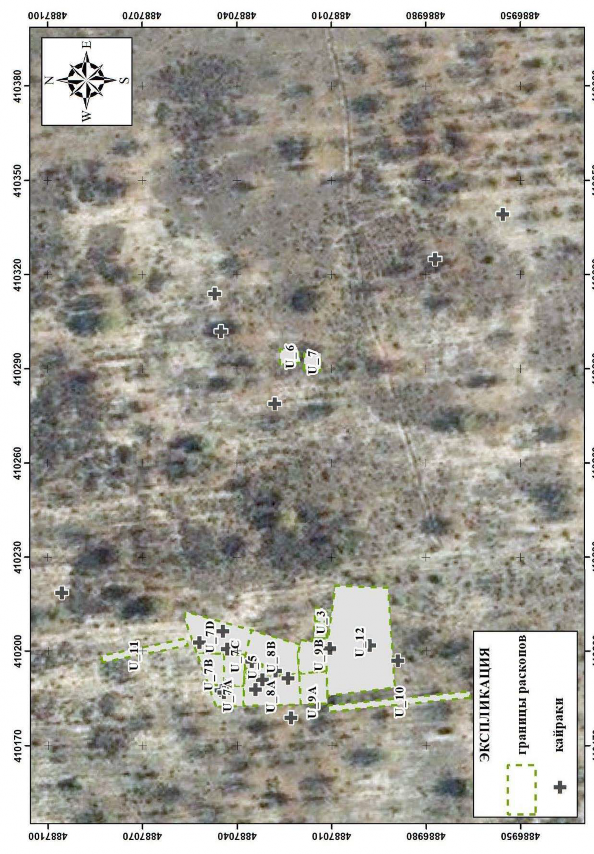

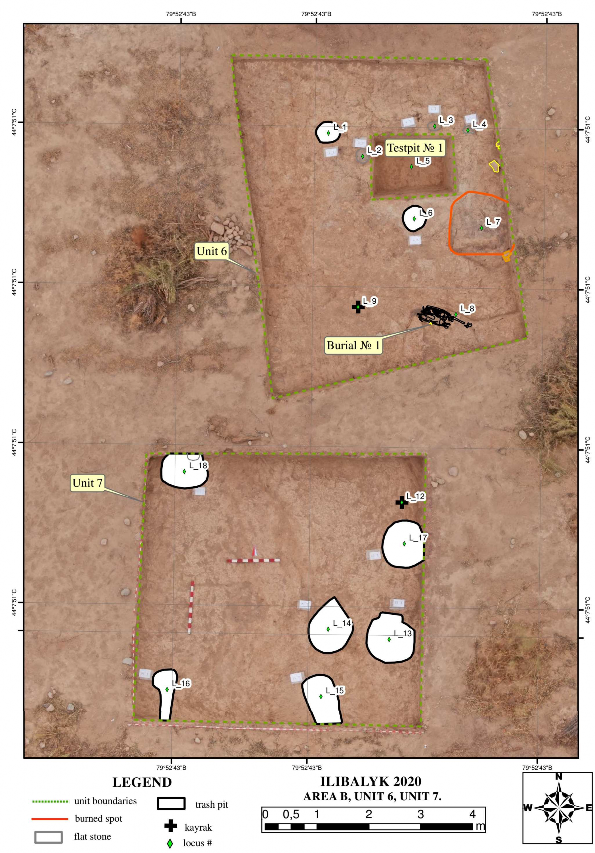

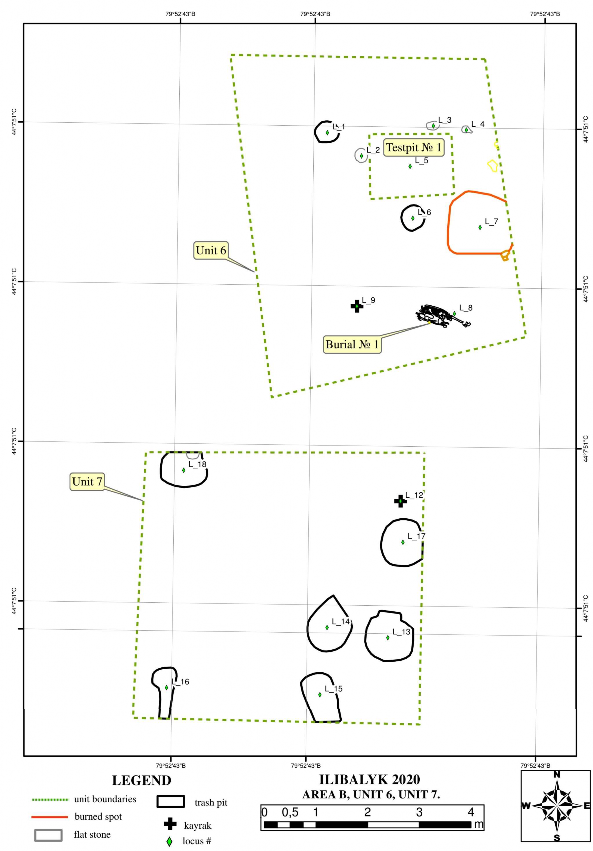

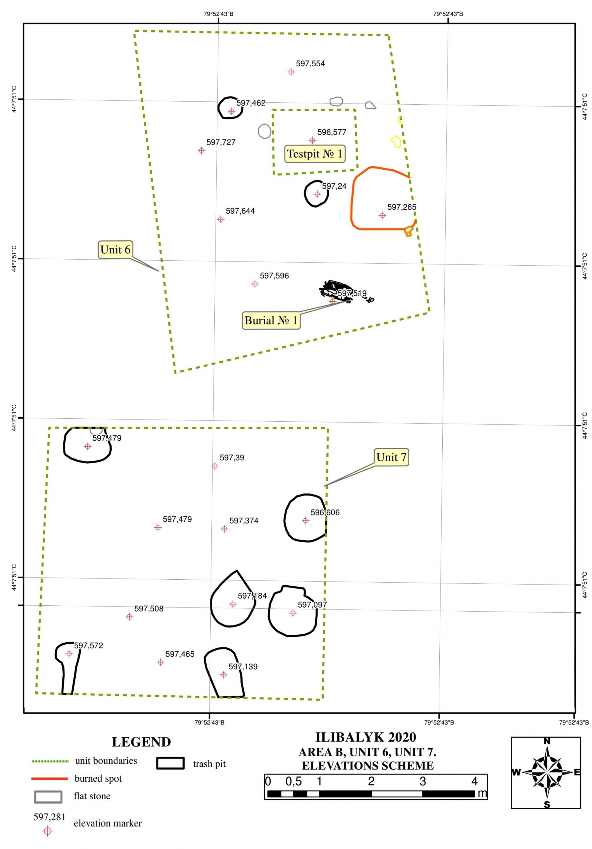

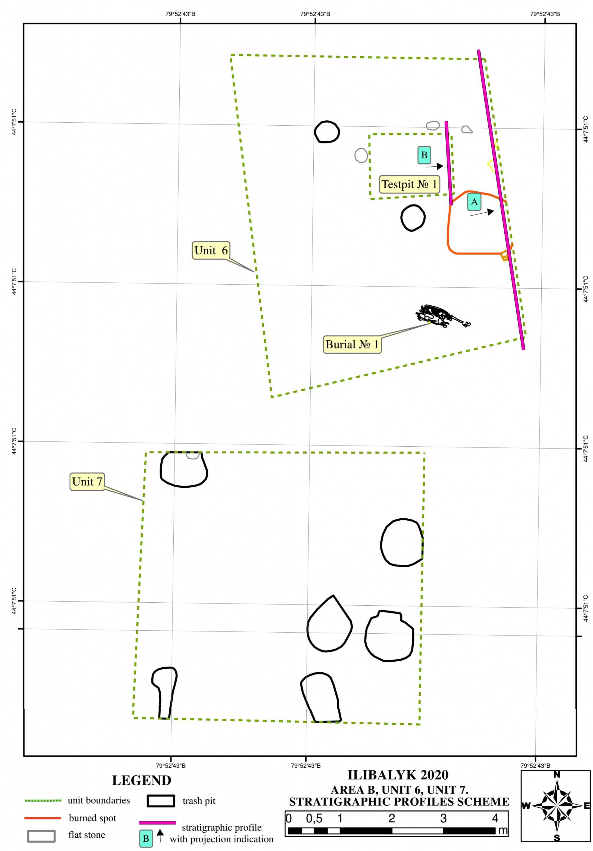

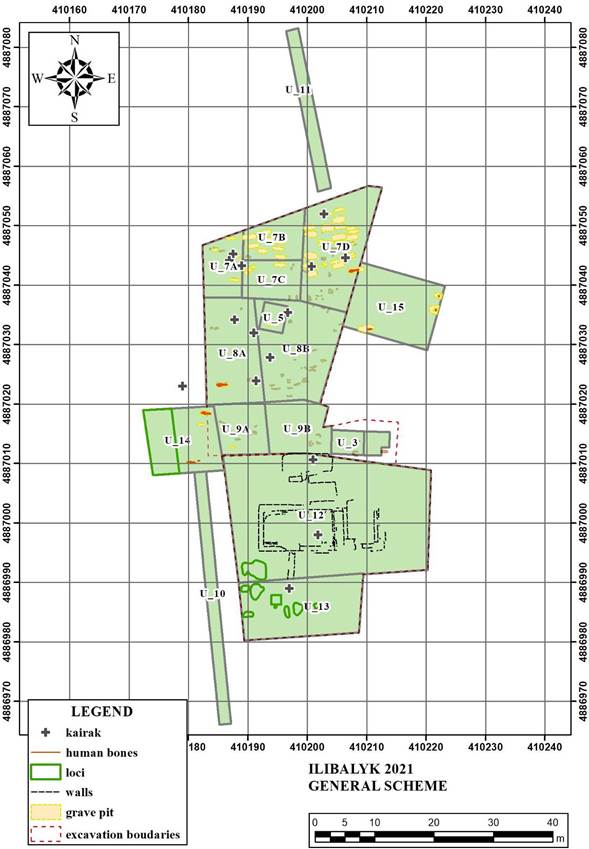

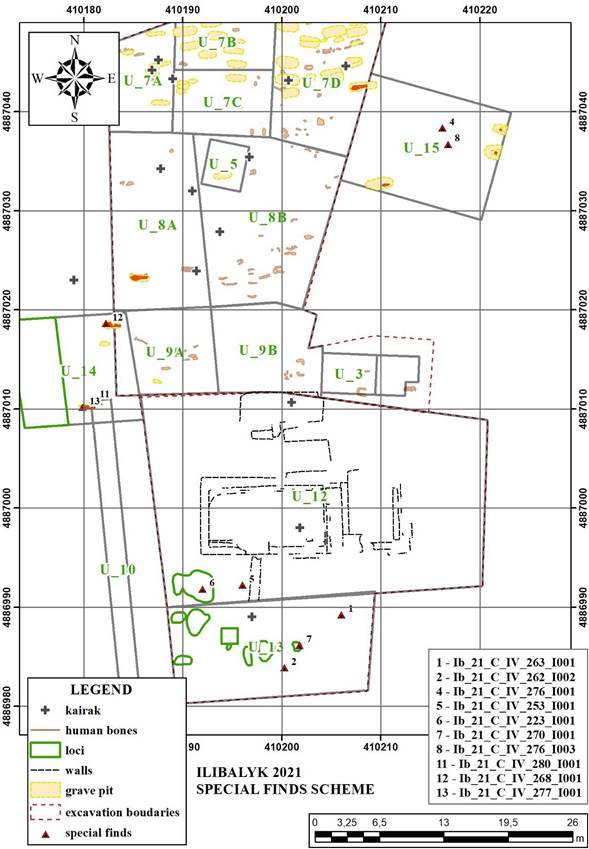

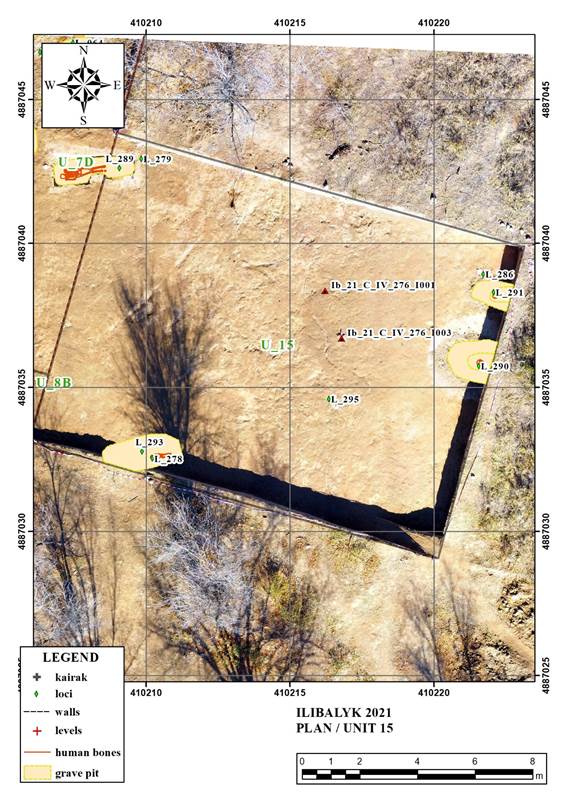

As a result, three excavation units were delineated: Units 6, 7 (in Area B), and 12 (in Area C).

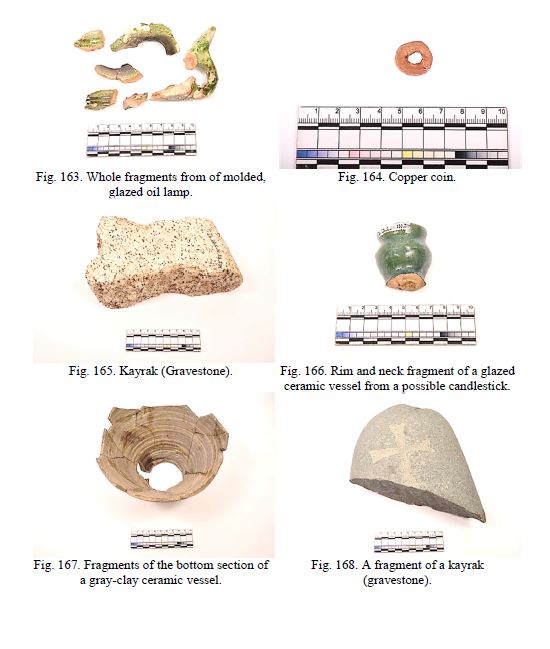

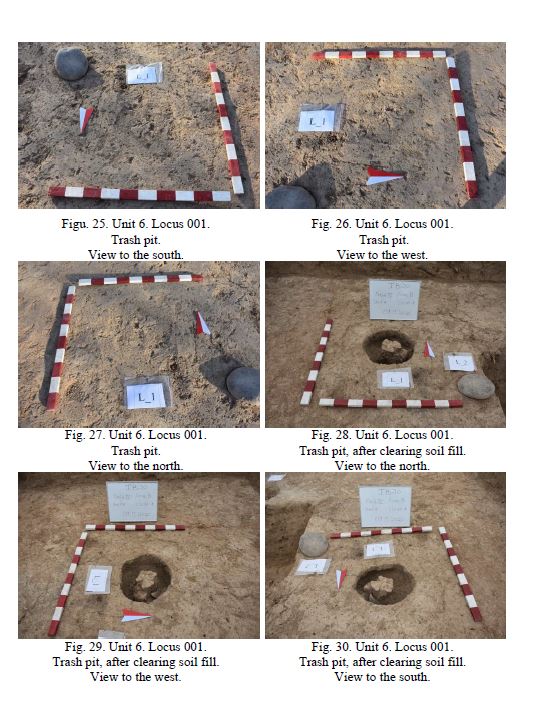

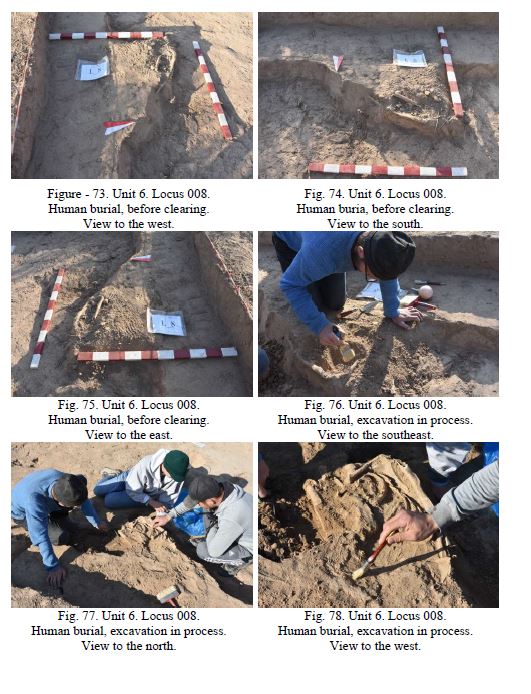

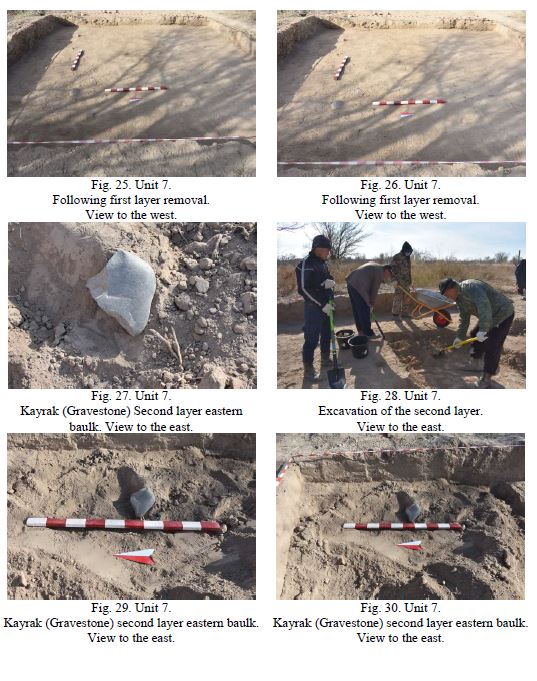

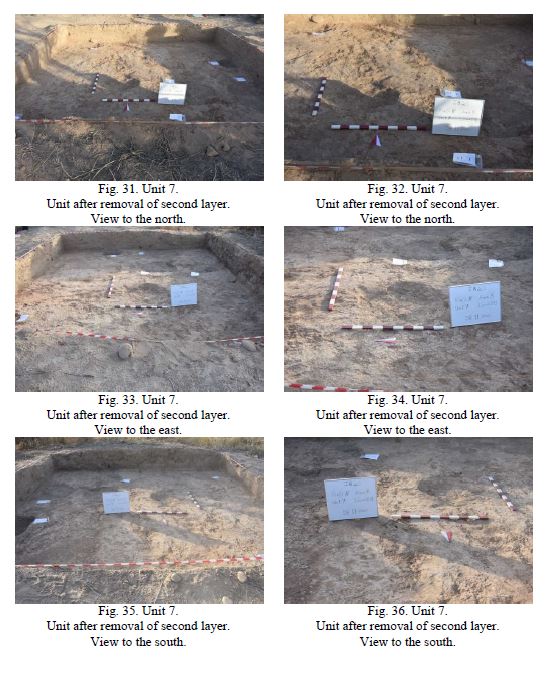

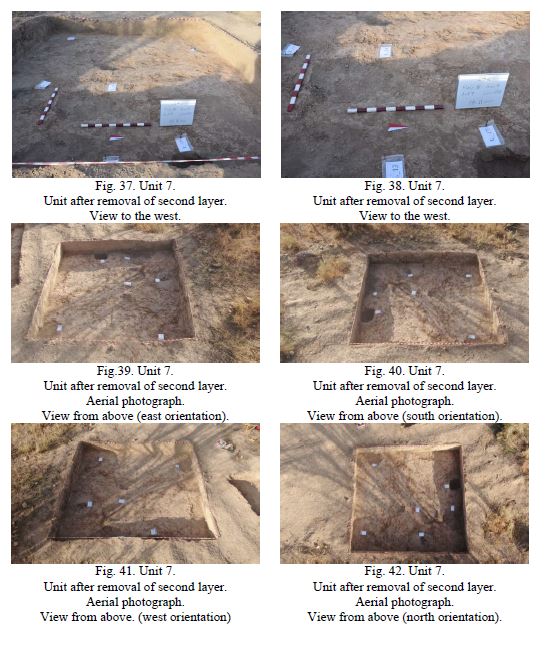

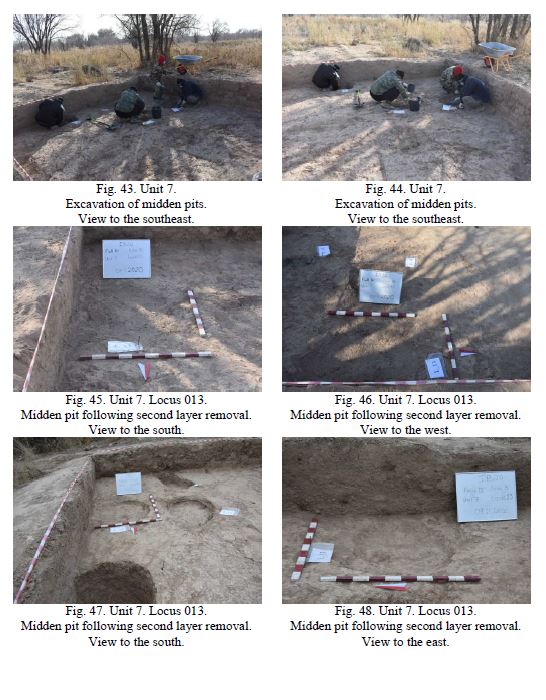

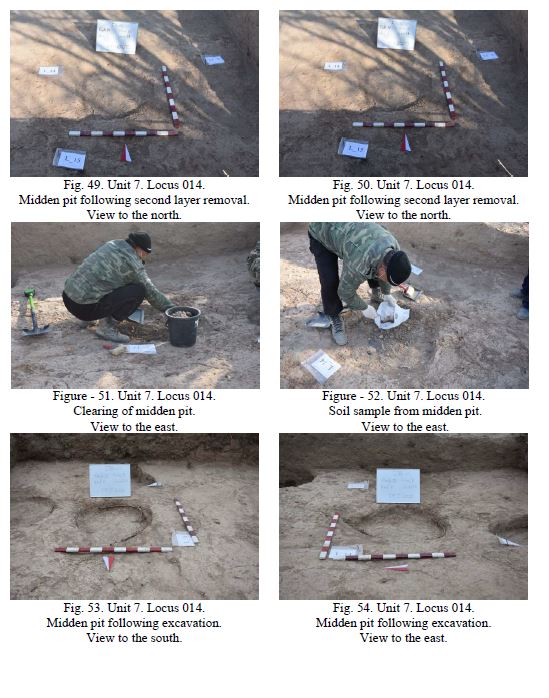

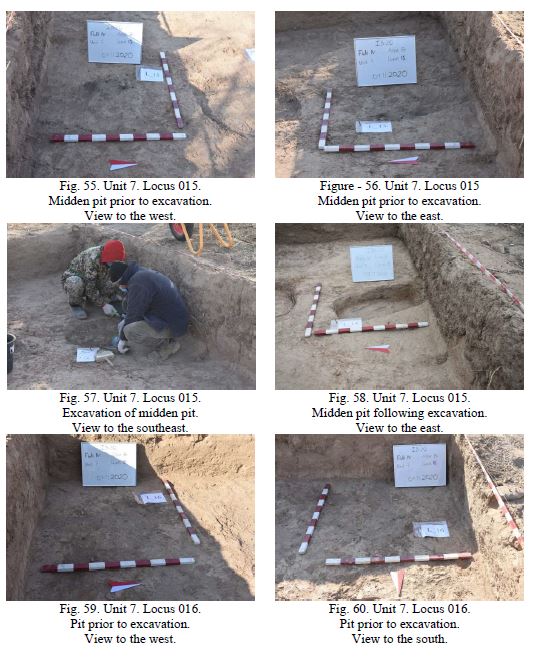

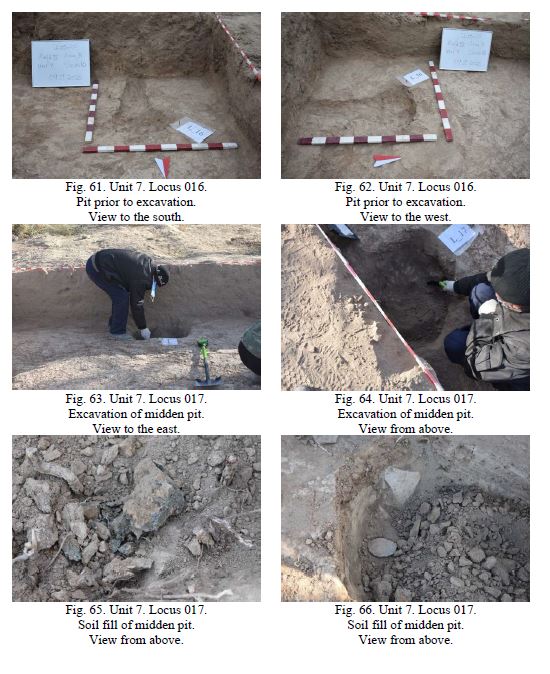

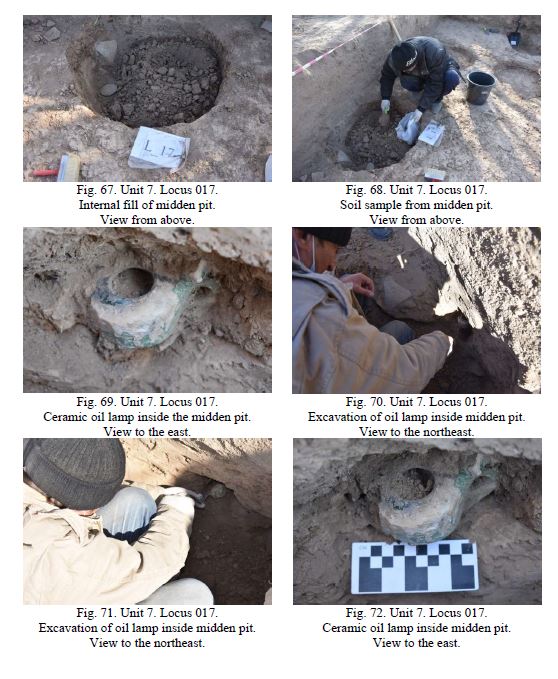

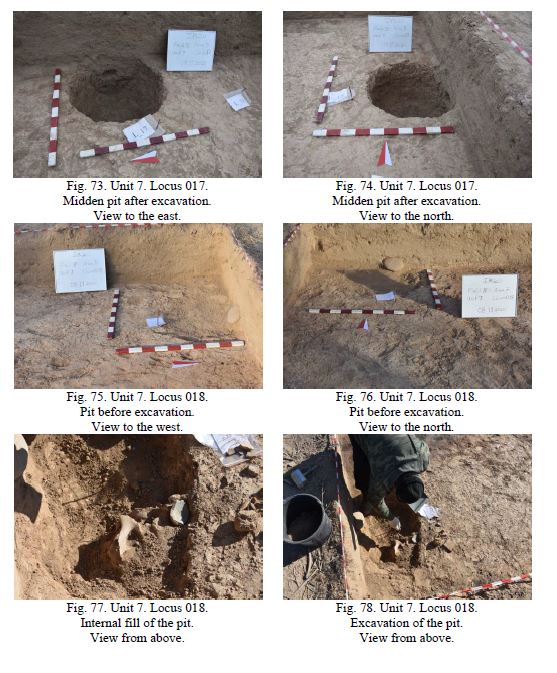

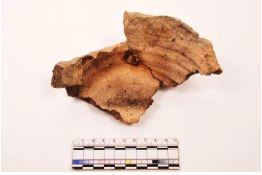

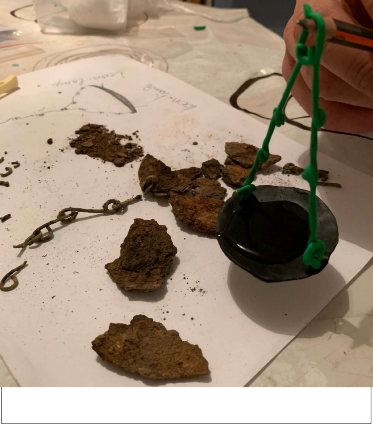

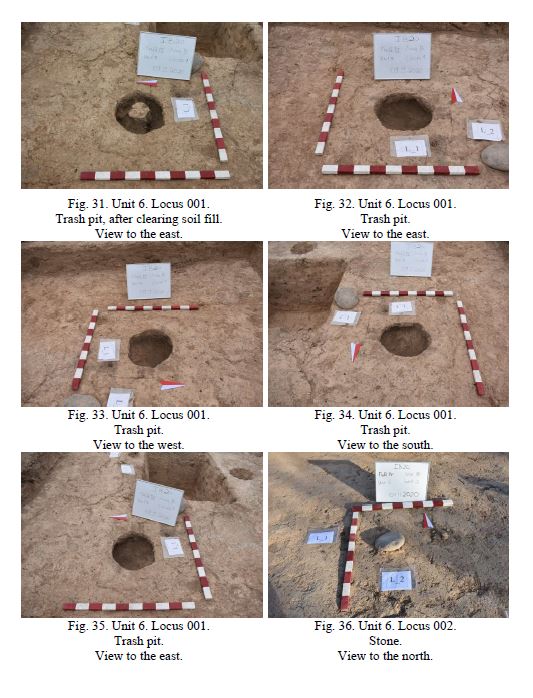

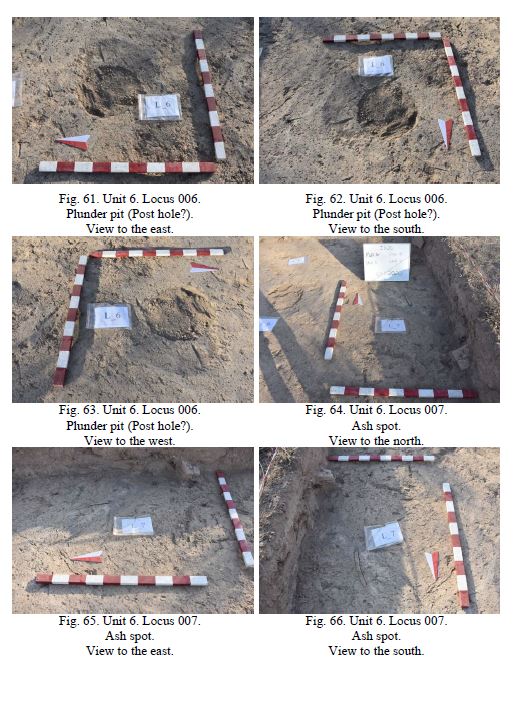

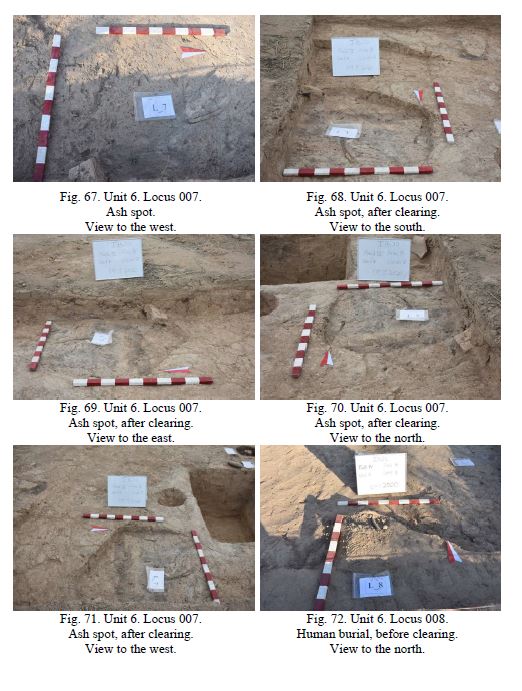

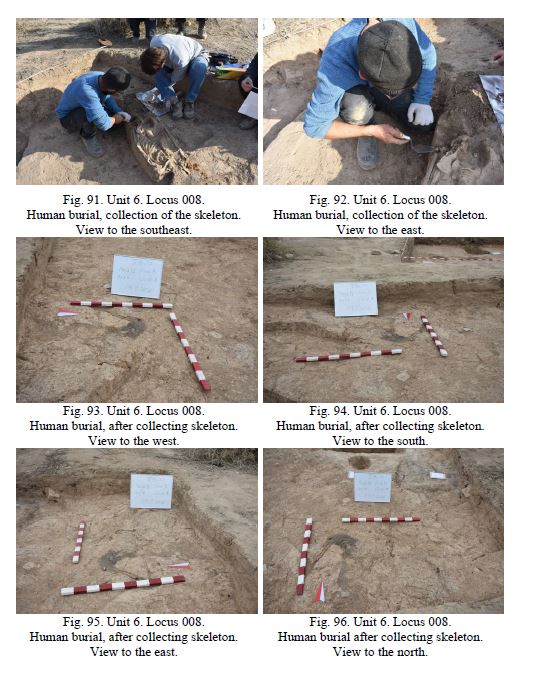

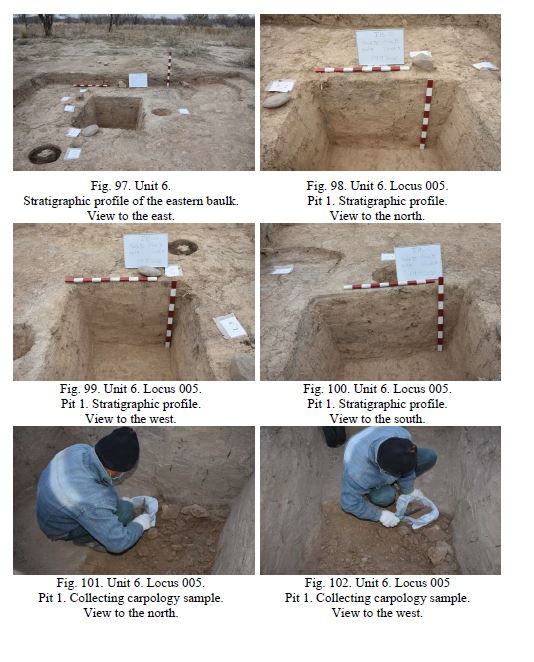

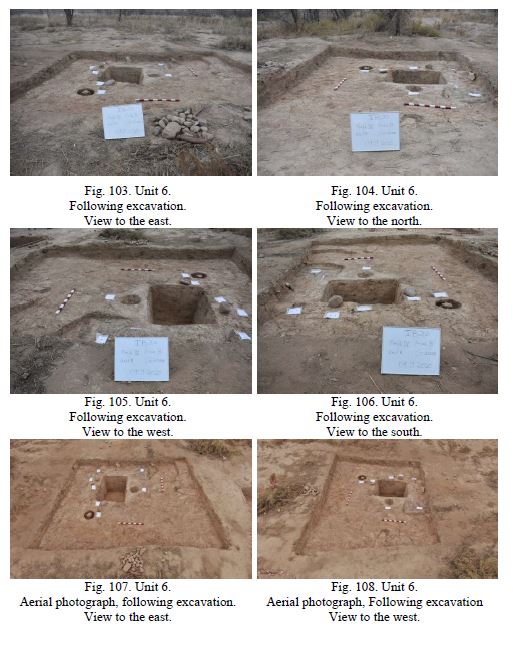

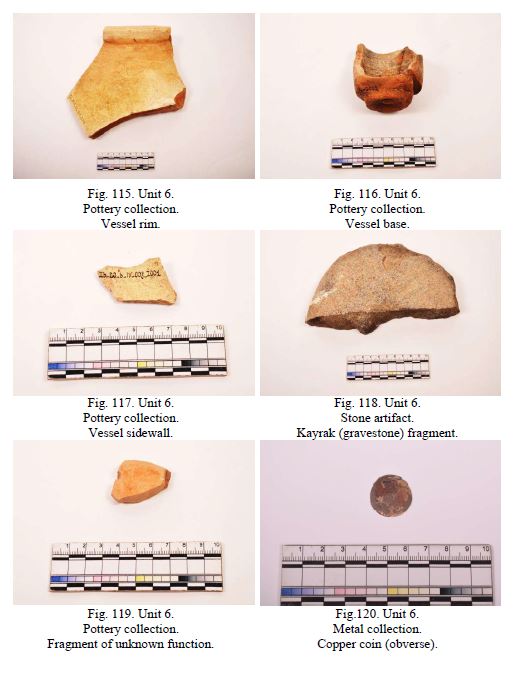

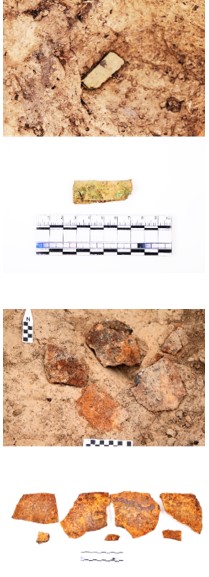

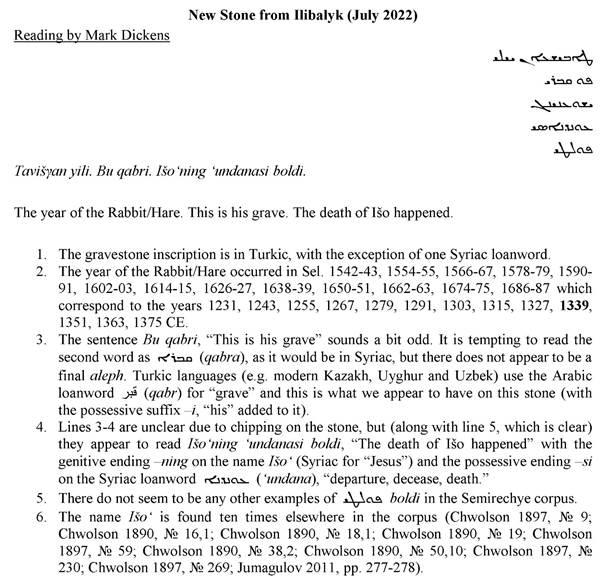

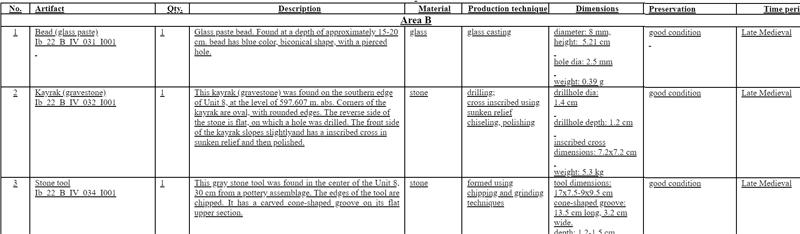

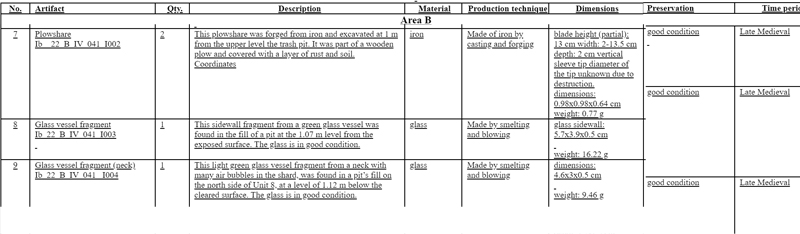

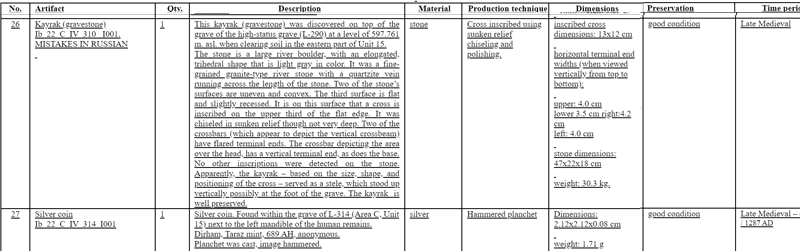

Units 6 and 7 (originally designated as test pits) were located 80 meters east of the previously identified necropolis. The excavation area was 60 m². Evidence of habitation were revealed in these units, represented by ash pits; middens; a large amount of ceramic material; as well as animal bones. Interestingly, along with evidence of occupation in this territory, elements related to the necropolis were also revealed which included one burial and two kayraks (gravestones). One contained a written inscription. While clarity on dating is still problematic it does appear possible that habitation and the cemetery are chronologically related based on ceramic evidence.

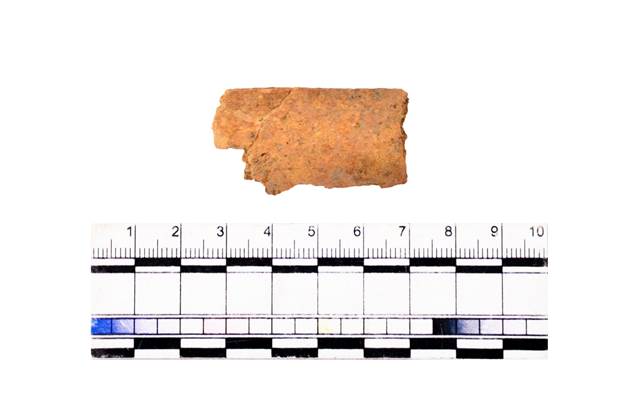

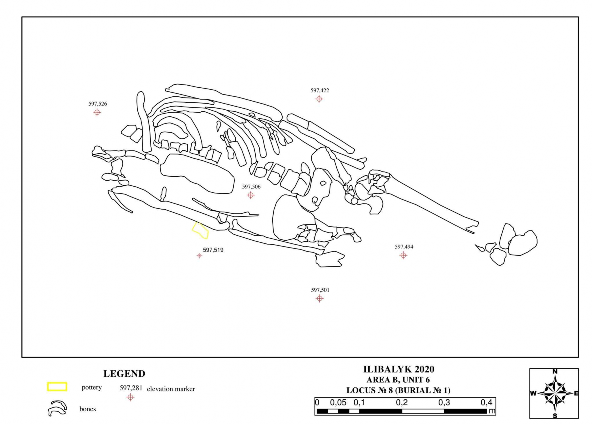

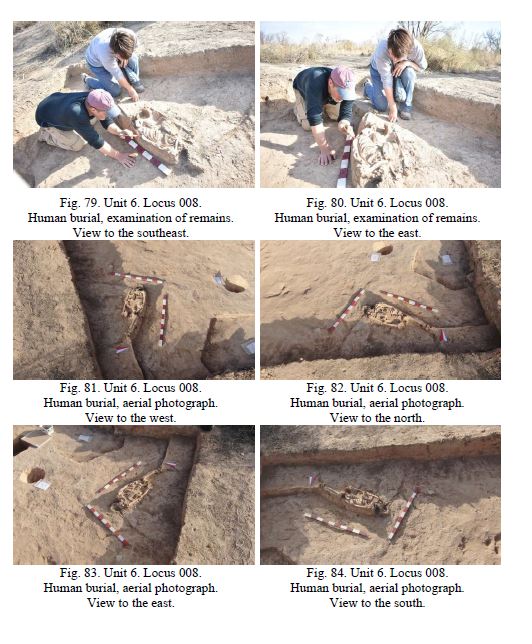

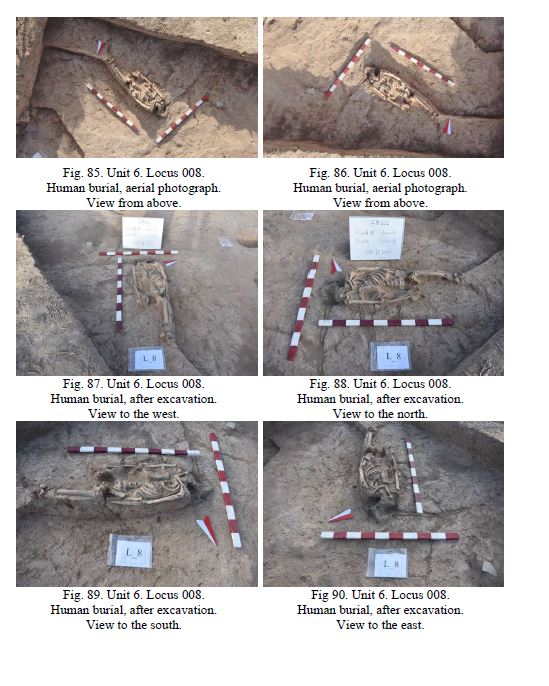

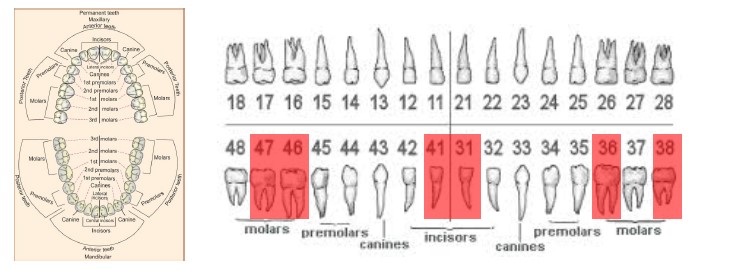

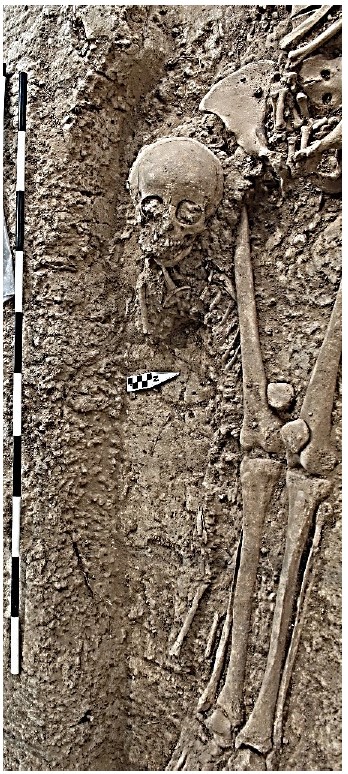

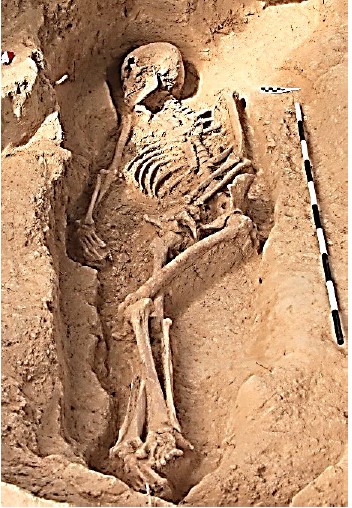

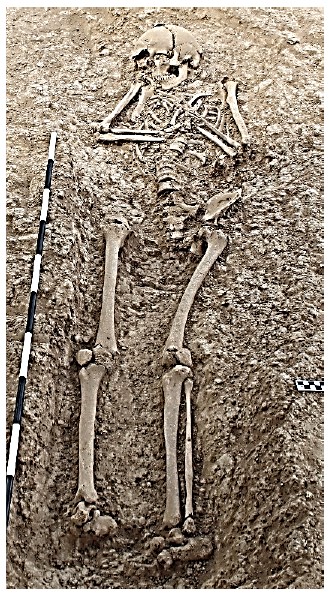

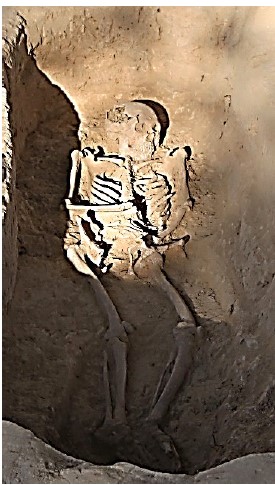

The remains of the discovered burial belong to an adult and the corpse’s position coincides with those previously studied with the head to the west, legs to the east, and extended on the back. The overall preservation of the bones was poor with the skull and feet missing, the hands appeared disturbed and were located under the pelvic bone. Apparently, the burial was damaged during agricultural plowing of the site during the Soviet era. A pottery sherd was found near the right elbow and an unidentified small piece of metal was found around the lower appendages.

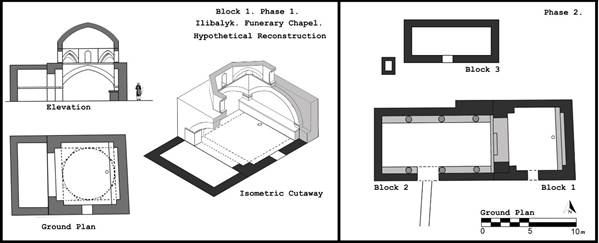

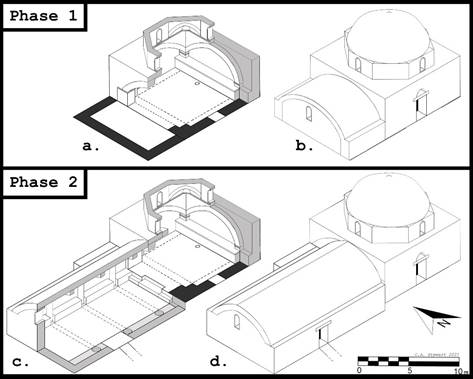

Excavations also revealed a rectangular building with dimensions of 21 x 8.7 meters, with a west-to-east orientation.

The building consisted of three rooms:

Room 1 was located in the western part of the building and occupied most of it. The dimensions of the room were 11.6 x 6 meters. Inside the building, from the northern and southern sides running along the walls, were ledges or platforms made of adobe bricks. The ledges measured 60 cm wide and 40 cm high. Five flat stones were found on these ledges, 3 on the northern ledge and 2 on the southern ledge. The stones were almost arranged parallel, but not exactly symmetrical from each other, which may have served as platforms for wooden columns, although this remains uncertain.

In the southeastern and northeastern parts of Room 1, the walls had a 4 x 0.5 meter-long outward indentation. Perhaps this location was a niche in the wall. A thick layer of clay plaster was found on the inner side of the northern niche indicating that the area was visible to the original occupants.

In the center of the southern wall of Room 1, a 2.5-meter gap was revealed. This gap may indicate an entrance to the premises.

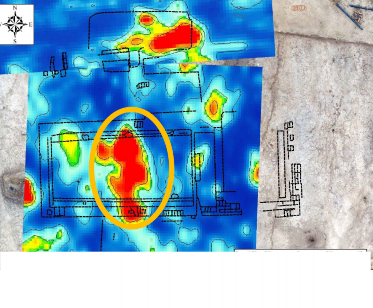

A large amount of charcoal was found on the floor of this room as well as within the soil fill. In the center of the room on the floor, there were three spots of calcined clay, which indicated the presence of burning.

The floor level of the room was sunken by 40 cm relative to the other occupational surface.

Room 2 was located to the west of Room 1. This room appeared to be a raised platform located 60 cm above the floor of Room 1. Rooms 1 and 2 were separated by a partition made of mud blocks measuring 2.1 x 0.3 meters and located exactly in the middle of the western edge of Room 2. The room itself measured of 5.9 x 1.6 m. The northern wall of the room has either not survived or perhaps this area was an entrance. The floor level in Room 2 corresponded to that of the level of the medieval occupational surface.

Room 3 contained the remainder of the eastern part of the building. The northern wall survived only in the northwestern part as seen in the traces of plaster. The western and eastern walls of this room were different from the rest of the walls of the building as they are made of pakhsa (tamped earth) fill, while the other walls were constructed from adobe blocks. A tandoor (furnace) was located at the edge of the western wall of room 3. The dimensions of the room were 4.5 x 7.4 meters and extended in a north-south direction.

To the north of Room 1, outside the building, is an adjoining area made of tamped, gray soil interspersed with charcoal. It was not possible to determine the full configuration of this feature, but presumably it represented two rectangular sections connected by a corridor. On the perimeter of this feature were traces of plaster and adobe blocks were found in certain sections. In the southeastern corner of this section, 4 fired, square-shaped bricks were found. They were possibly the remains of an entrance to room 2.

To the south of room 1, opposite the presumed entrance, the remnants of mudbricks were found which formed a meter-wide platform that extended in a north-south direction. Currently, it is assumed that this platform could be a pedestrian pavement leading to the entrance.

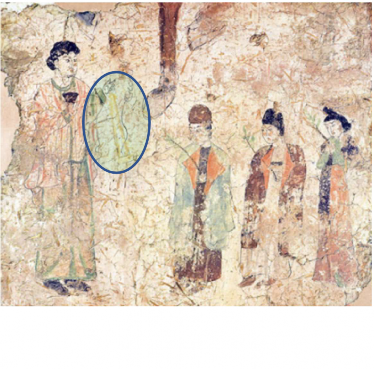

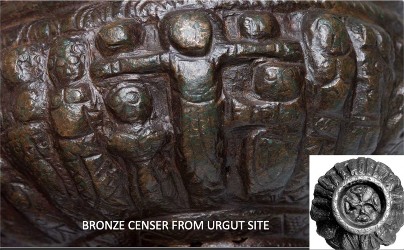

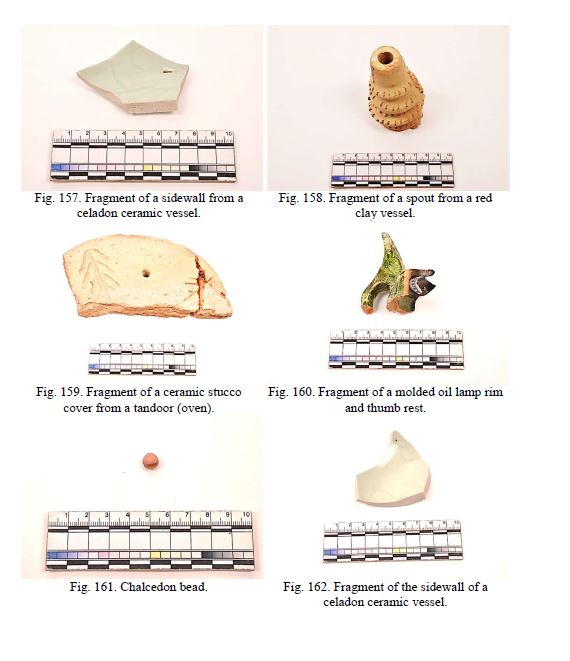

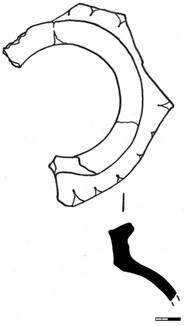

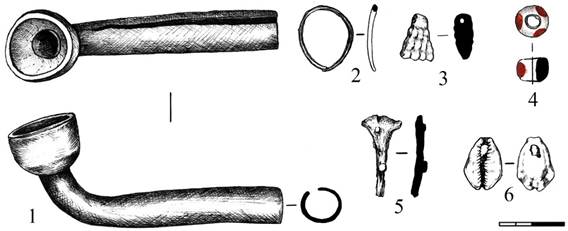

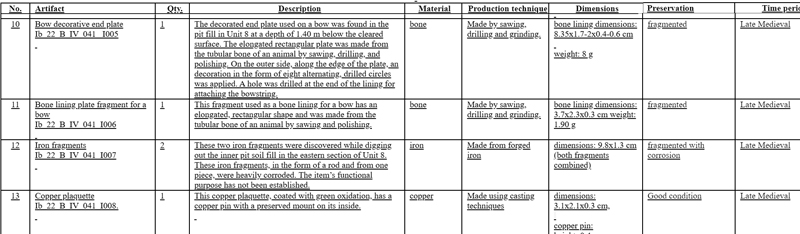

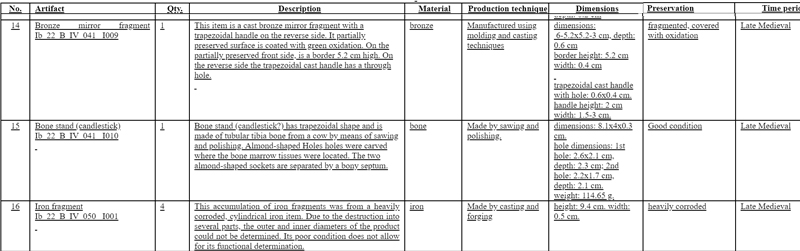

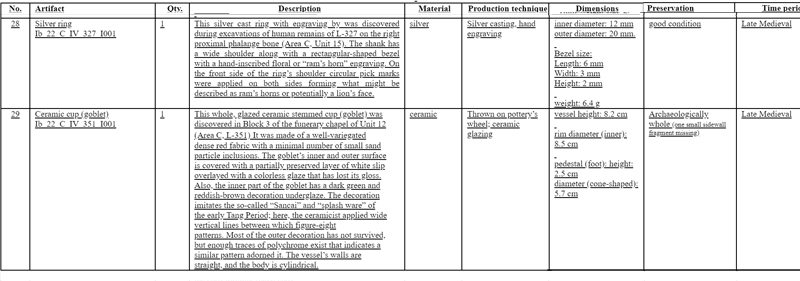

Cultural material within Unit 12 included a large amount of common ware pottery consistent with a 12th through 14th century chronology. Animal bones also indicate that food consumption occurred on the premises. However, most significantly, high status glaze ware and celadon finds, including ceramic lamps with thumb rests with floral designs of a cruciform shape as well as a possible open air metal lamp or censer, indicate the space possessed a possible ecclesiastical function.

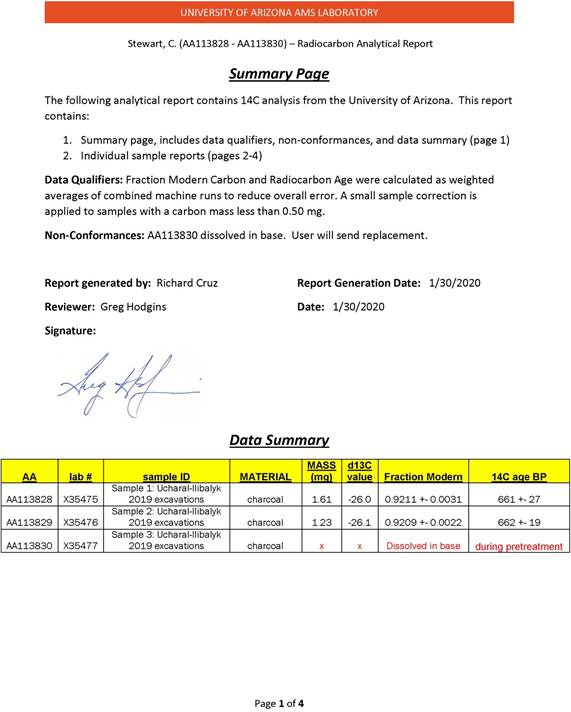

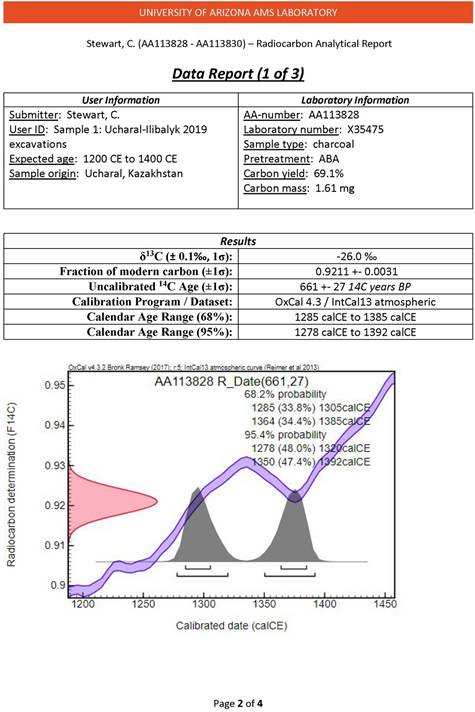

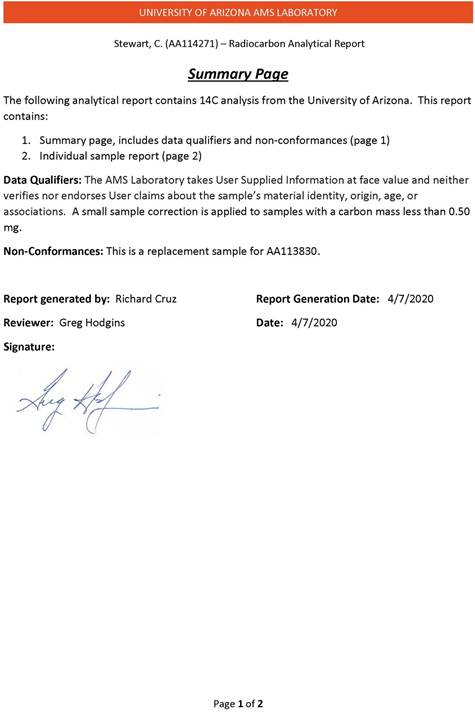

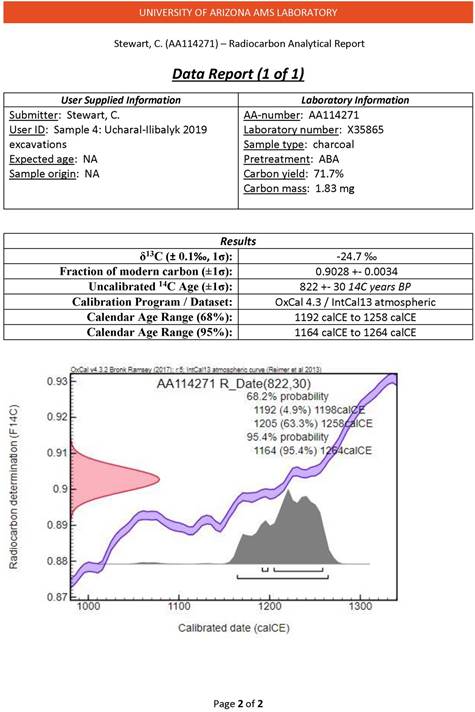

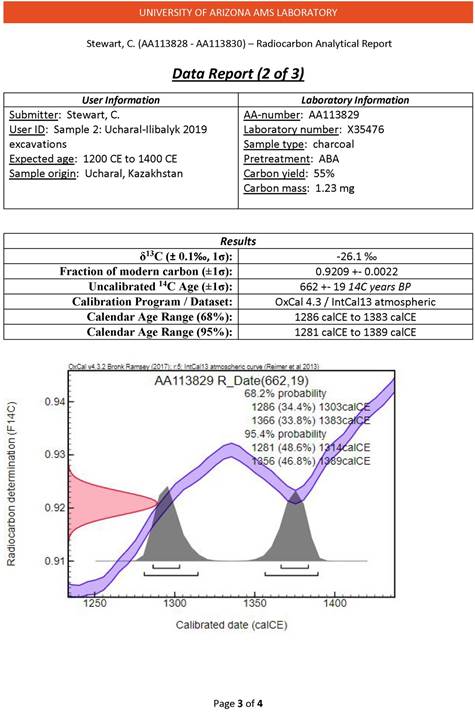

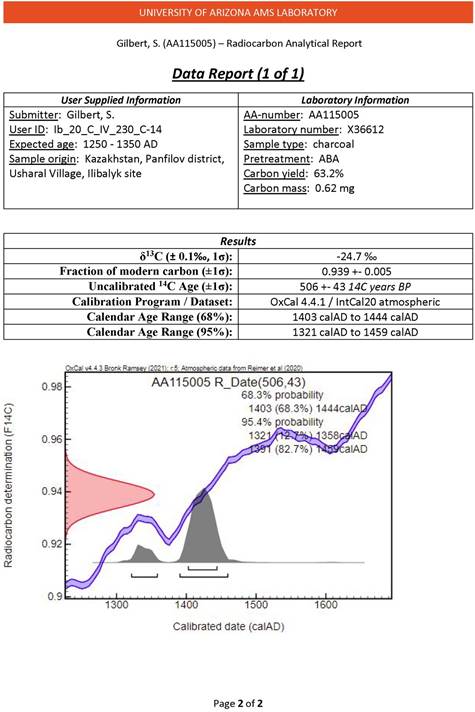

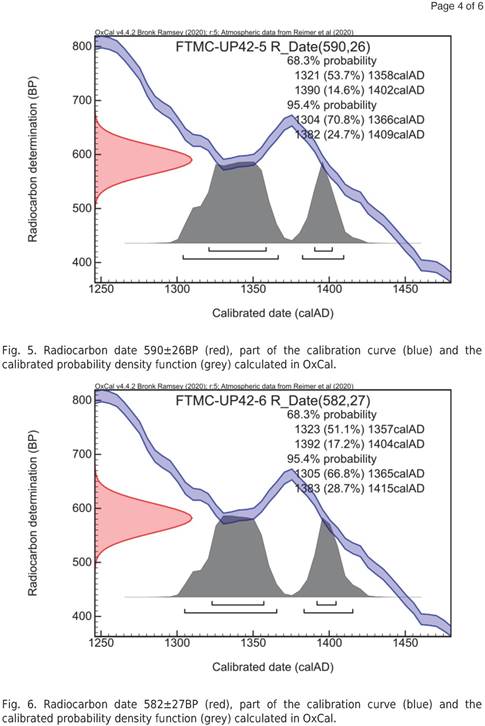

Based on the above, we can conclude that in 2020 at the excavation site of Unit 12, a building with a ritualistic function has been discovered which is geographically associated with the necropolis. Based on similar buildings found at medieval Christian necropolises, the current interpretation is that this structure was a small Christian church or funerary chapel. Evidence in the soil of Unit 12 also suggests that the structure burned and was never rebuilt. Radiocarbon analysis of a piece of charred wood from within Room 1 of the structure was submitted to the University of Arizona’s Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Lab (USA) and results are pending as of March 31, 2021. Once those results are obtained and addendum will be included in the report.

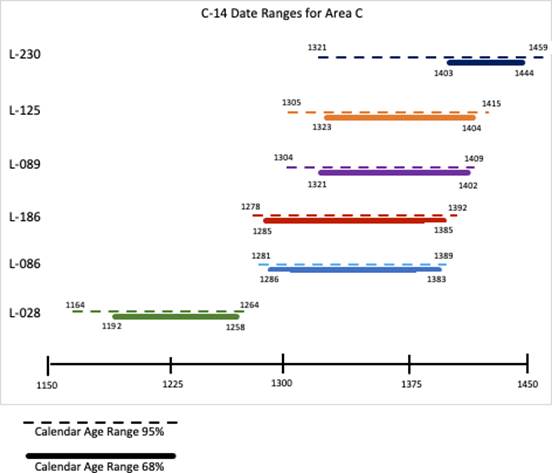

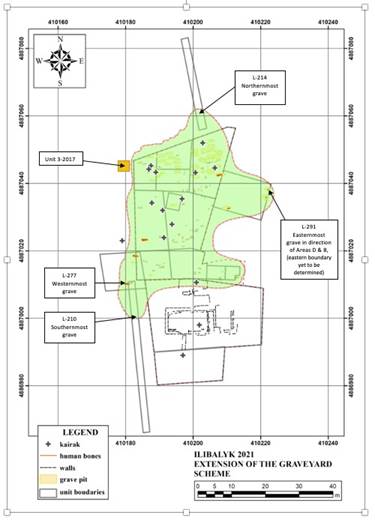

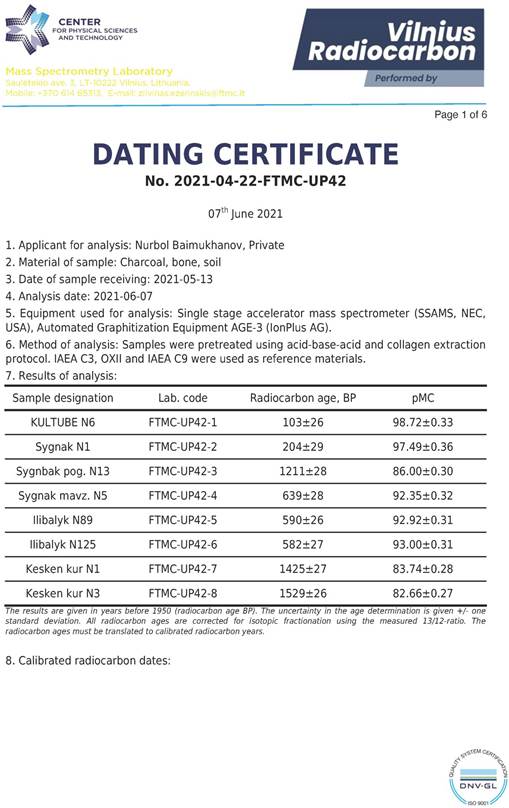

Excavations of Units 6 and 7 (originally designated as test pits) identified a burial which indicates the furthermost eastern extent of the cemetery, so far established. Whether other burials lie further east is still an open question, but the current eastern limit, due to the discovery of this grave, extends the cemetery by an additional 80 meters. The presence of two kayraks (gravestones) along with a burial utilizing traditional Christian rites, which are homogeneous throughout the cemetery, clearly indicate that there was also a cemetery on the section designated as Area B which lies due east of Areas C and D. Currently, it is impossible to say whether the cemetery occupied the entire territory between Area C and Unit 6 where the burial was revealed or if gaps exist between what we have discovered in Area C and Area B. This will have to be explored hopefully at a later date. The cultural material from the ceramic collection discovered provide a date range from the 13th -14th centuries, which is consistent with the radiocarbon samples taken in 2016 and 2019 from two different locations in and around the cemetery and can be compared with the most recently submitted sample once those results are available.

Introduction

The focus of archaeological research for the 2020 Ilibalyk expedition was the Christian cemetery of the Ilibalyk settlement, located in the Panfilov district of the Almaty oblast on the northern outskirts of the village of Usharal, in the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Purpose of the work:

Research was conducted on the site of the western rabad (suburban district) in order to obtain additional data on the cemetery and to identify new cultural material related to the Christian community of the medieval city of Ilibalyk.

Goals:

-

To determine the limits of the cemetery to the south and east of the identified boundaries as revealed during the 2019 excavation.

-

To identify potential architectural features in Field IV (the western part of the rabad

(suburban district)) related to the cemetery.

-

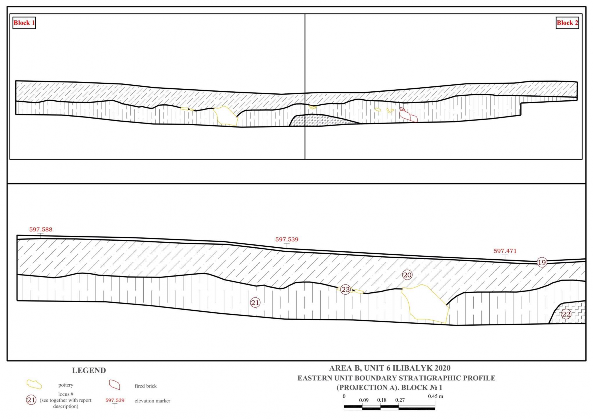

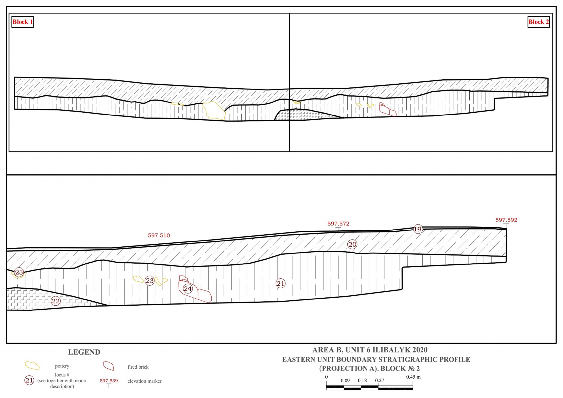

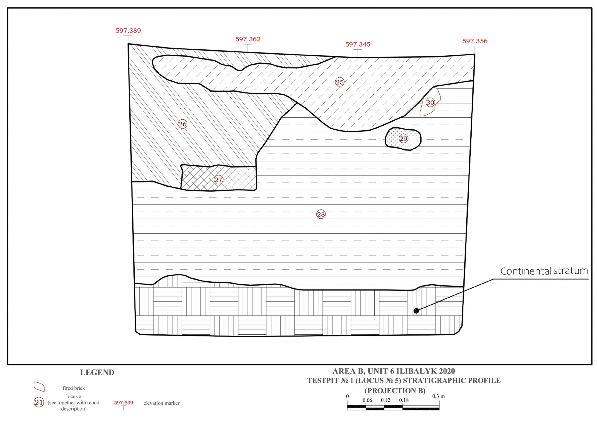

To identify the revealed details of the archaeological excavation and study the stratigraphy.

-

To conduct aerial photography, a tacheometric survey, and photogrammetry.

-

To conduct soil samples for natural science analysis and archaeological flotation.

-

To identify all the revealed details of the archaeological excavation by means of aerial photography, microtopography, tacheometric survey, and photographic recording.

-

To provide laboratory processing of the cultural materials and a graphic presentation of the results.

Based on these goals and objectives, an expedition was organized which included several specific groups and specialists who were responsible for carrying out the planned excavation which included the following:

-

A team of archaeologists. The task of this group was to carry out a series of investigations which involved the clearing and discovery of building structures aimed at providing detailed analysis of the cultural layers and cultural material including the discovery and analysis of materials from the ceramic and osteological collections; materials from metallurgy; and other artifacts.

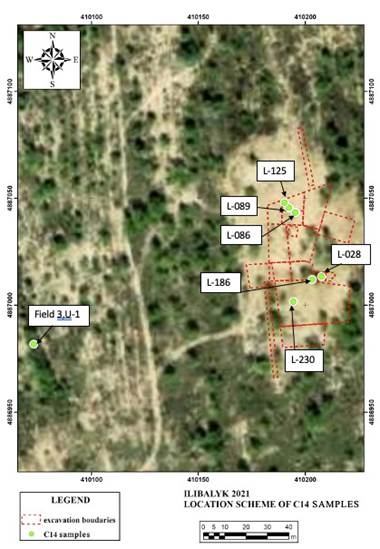

Also, this group collected samples for carpology, palynology, C-14 and flotation using generally accepted guidelines.

-

A recordation team. This team carried out the documentation of the entire process of archaeological investigations with the analysis of the results of the data obtained through the study of individual components of the Ilibalyk settlement and using advanced geodetic equipment. The resulting work of this group involved the construction of 3D models of the excavation sites; the creation of ortho-photomaps and stratigraphic profiles; detailed excavation plans; microtopography; and the development of plans which locate topographically the discovered materials.

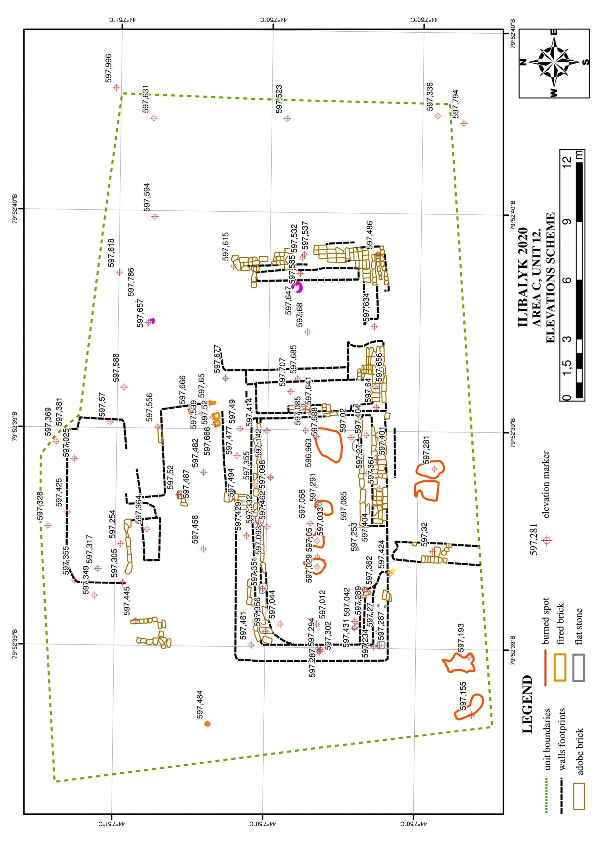

Documentation was carried out using a Leica TCR-407 total station with subsequent data processed in the AutoCAD and ArcGIS environment in parallel with photographic recordation of building structures and photogrammetry utilizing a Phantom-4 unmanned aerial vehicle.

In the process of conducting preliminary aerial photography, the following tasks were performed:

-

Preparation of the site by clearing the areas of grass and underbrush which creates difficulties in scanning. In addition, the site was cleared of modern household waste (glass, metal, etc.)

-

A breakdown of the entire excavation area into sections/units was made. The findings are reflected in the appendix of this report.

-

A team of ceramic technologists was formed for the task of processing the cultural material to study the production technology and provide a description of the ceramic collection and other discovered materials; draw the ceramics and other finds and record them in a spreadsheet of arranged tables. This team also reconstructed ceramic vessels and collected statistical data.

-

A team for logistical processing. The task of this group was to process the discovered cultural materials of the ceramic and osteological collections, as well as metal products and other artifacts by means of washing and cleaning ceramic and osteological materials in compliance with the conditions and the storage location. Metallic materials were processed in accordance with methodological recommendations and interpreted by specialists. All materials were carefully processed, labeled, and described with an individual serial number for each piece of material. The obtained data is displayed in the appendices of this report.

The main priority involved the implementation of the planned activities for the analysis and documentation of materials and elements of the building structures of the area of occupation discovered during the archaeological excavation.

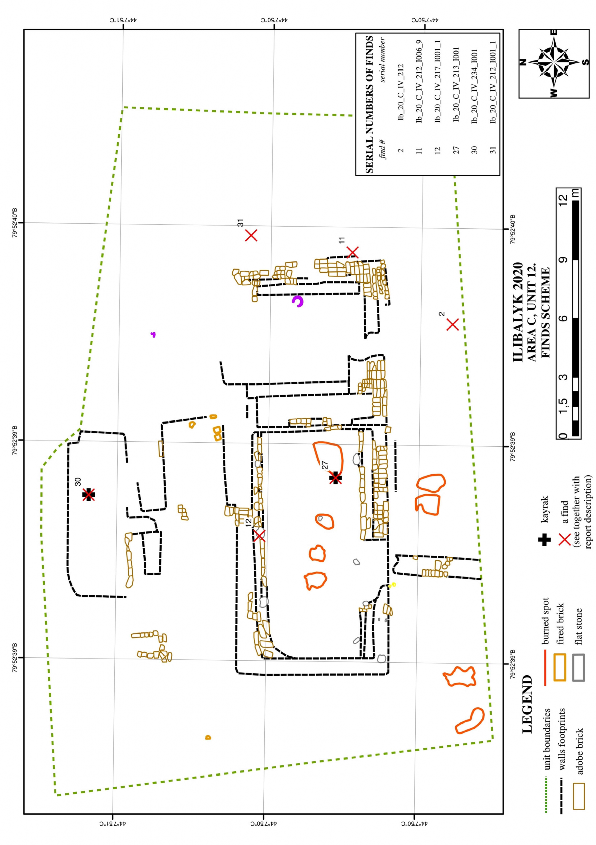

The cultural material found as a result of the abovementioned investigations were assigned a special serial number and special finds were measured using the theodolite- tacheometer and coordinates were obtained in the UTM system. These materials are displayed on the excavation top plan. All the material discovered as a result of the excavation have been carefully processed and cleaned in controlled conditions.

On the basis of the description and photographic record of the cultural materials from the excavation, a collection inventory was created, a general record was made, and statistical data of the revealed materials were established. Then, these materials were documented, packaged, and prepared for transfer in accordance with documentary regulations.

Once the excavation identified and cleared the building structures, descriptions were made of the identified components followed by design and drawing documentation.

This particular work was carried out by documentary specialists who know the latest methods and modern technologies in the field of geodesy and planography. In the course of this work, drawings of the identified elements, a general view of the excavation, and stratigraphic profiles were created.

The methodological basis of the excavation was conducted with the following components:

-

Excavations across wide areas.

-

Layer-by-layer and elevation recordation of the work performed.

-

Development of a detailed plan of the identified structures using electronic tacheometers.

-

A methodical, comparative analysis for the study of finds.

-

A recordation method for establishing the stratigraphic and planographic situation.

-

A method of including archeological features into a geographic information system (GIS) for their precise positioning in space relative to each other and the landscape background.

-

The collection of documentation is based on a system developed by specialists from the University of Aachen under the guidance of Professor Michael Jansen and Dr. Thomas Urban. This system is based on the completion of specially designed forms, whereby a certain level of data collection is achieved. While the presence of a field diary does not serve as the basis for reaching the desired level, the researcher is presented with a series of so-called forms.

The "Main form," providing a general description of a site or a separate excavation, as well as a description of plans, goals, objectives and ways to achieve them.

An "Action sheet" is a type of field diary, in which the researcher enters daily information about the actions performed, as well as about the objects found, sizes, etc.

“A Locus Sheet” is a detailed account of each feature detected, the layer removed, or a specific feature noticed, etc., and is called a "locus" followed by being assigned a locus number.

"Find Tag or Label" is a form that is set up specifically for certain finds that are clearly different from the bulk of the excavated material.

A "Photograph Log" is a type of database with a catalog of photographs taken during the excavation, indicating the location, the direction of the shot, followed by a brief description, etc.

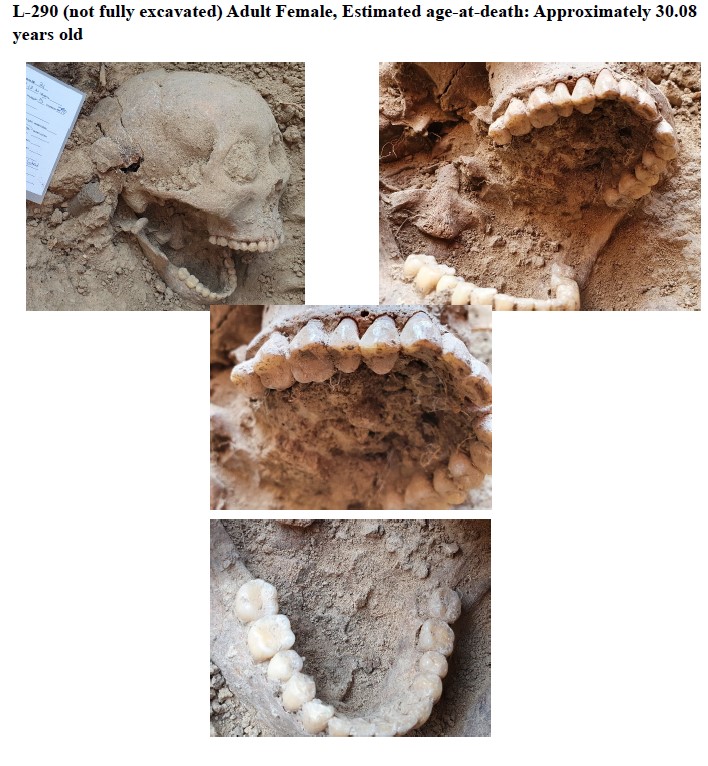

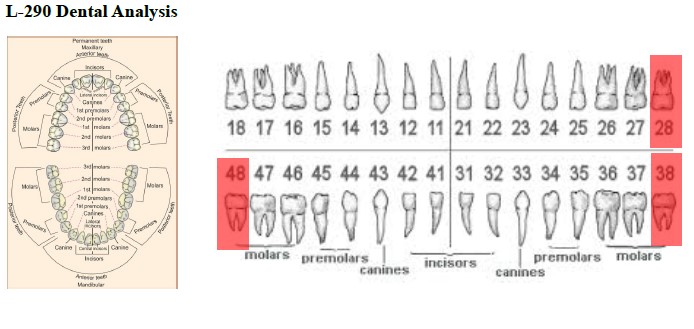

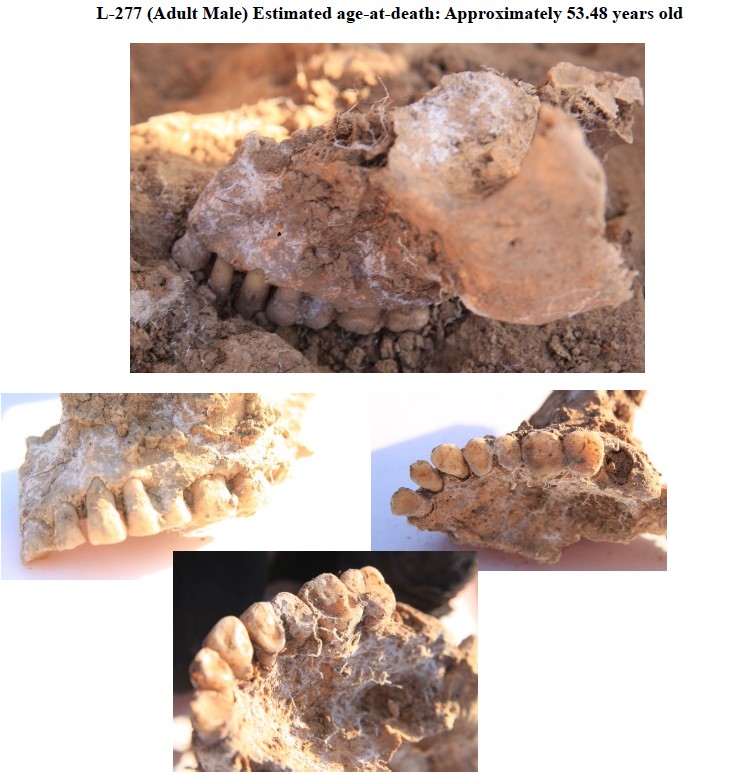

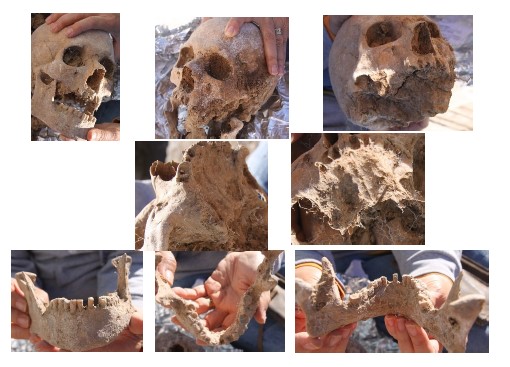

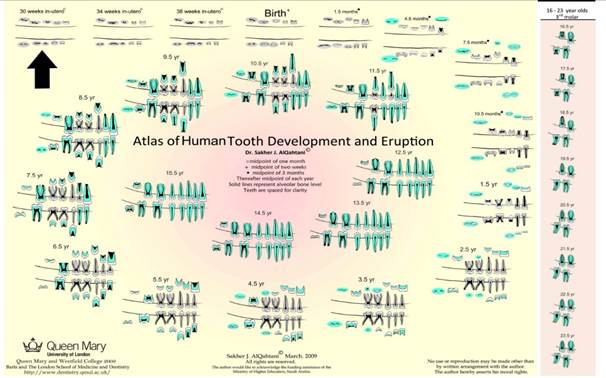

When human remains are discovered, an “Osteological Worksheet” is completed that aids the archaeologist in the process of examining the features of the burial and skeletal remains to provide rudimentary and preliminary identification of sex and age for adult remains. Our team does not have an osteoarcheologist or forensic scientist, therefore, any conclusions concerning human remains need to be considered as preliminary and in need of further examination by a specialist.

The team also included a brigade of local workers from both the village of Usharal itself as well as from other locations within Kazakhstan who assisted with excavation, photography, soil shifting, and recordation. Excavation involved the use of shovels, small hand tools, trowels, and dental tools. During the conservation and backfill stage at the conclusion of this year’s dig, mechanized equipment was utilized for that purpose.

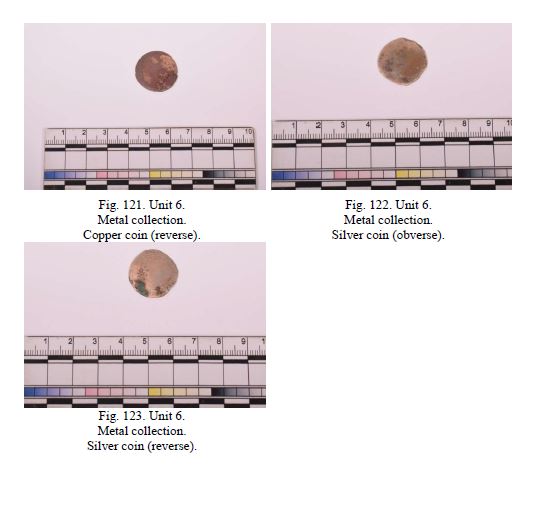

A metal detectorist was also used in controlled conditions to assist excavators with metal finds. Findspots were carefully recorded using the total station.

We would also like to acknowledge our gratitude to the people of Usharal village in the Panfilov district in the Republic of Kazakhstan, both in their assistance as workers on the site who cooperated with our adjusted Covid-19 protocols as well as other local Kazakhstani workers and volunteers who provide their skills and talents toward this project.

General Section

-

Description of the Excavation

-

Unit 12 (Area C) General Description

-

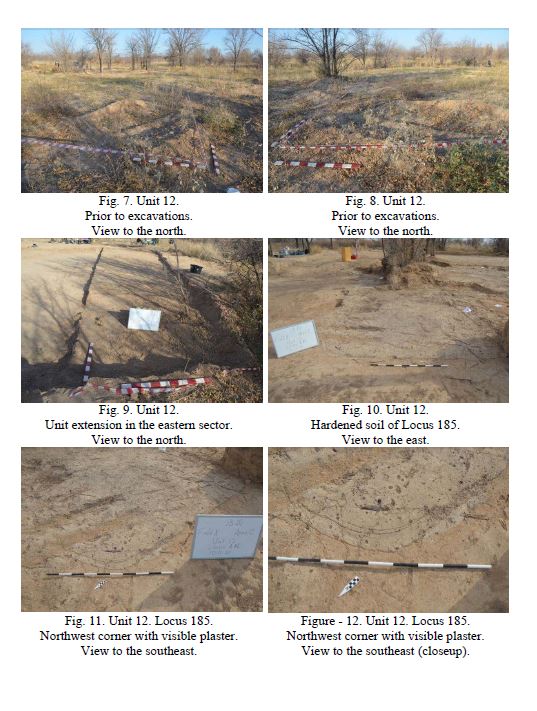

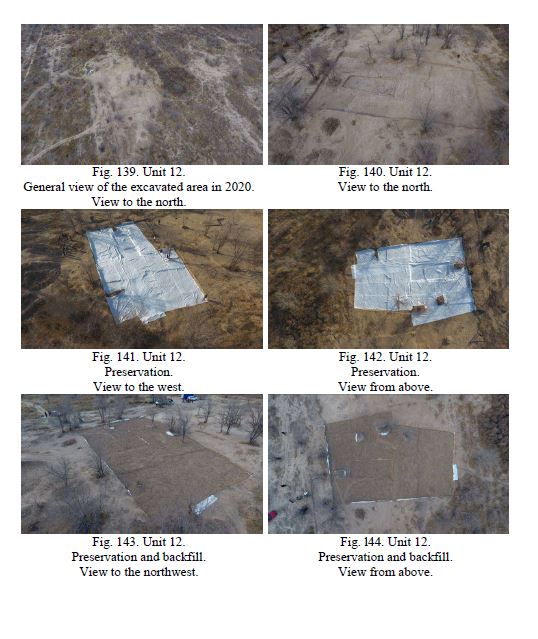

Unit 12 was a continuation southward of the 2019 excavation (Area C).

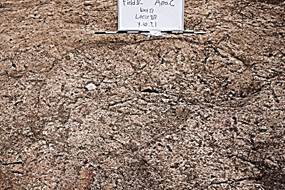

Residential buildings, a small scattering of local businesses, and a small guest house can be found to the north, west, and southwest of the excavation site approximately half a kilometer away. Prior to all excavations which began in 2016, this site has served as a grazing area for cattle and sheep, and as a result the area is covered with cow and sheep excrement. Traces of modern agriculture are also visible on the surface of the excavation site since the area was extensively plowed during the Soviet period beginning in the 1930s.

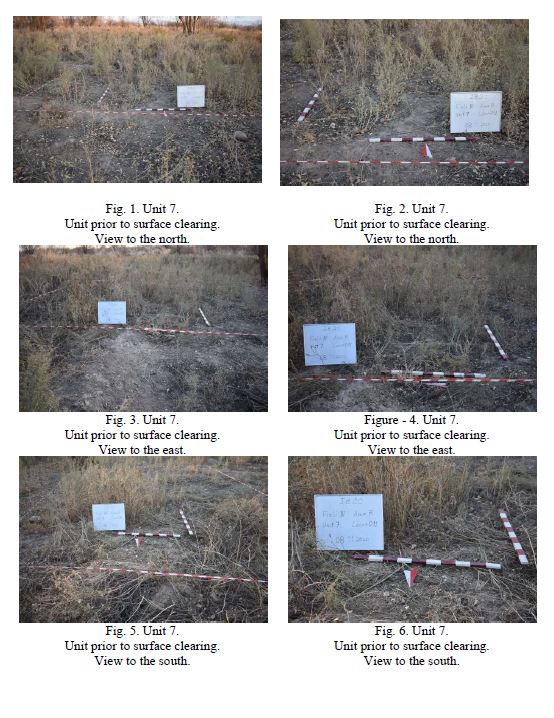

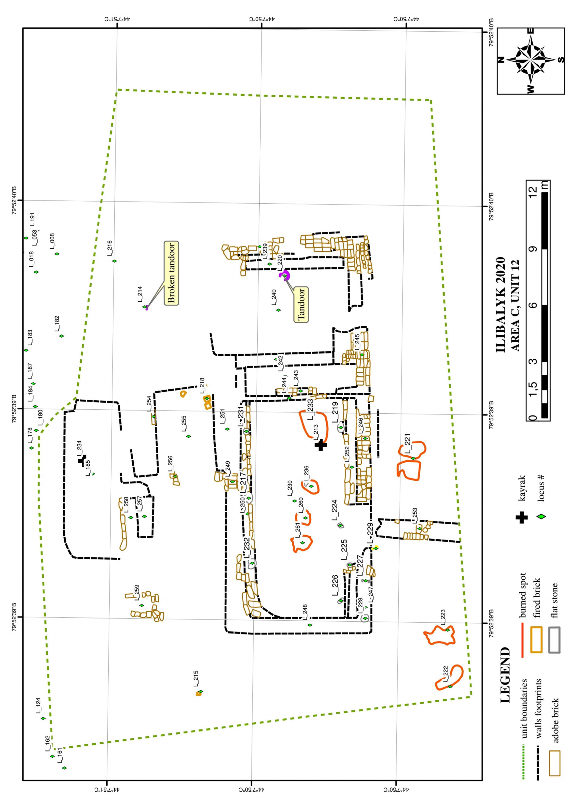

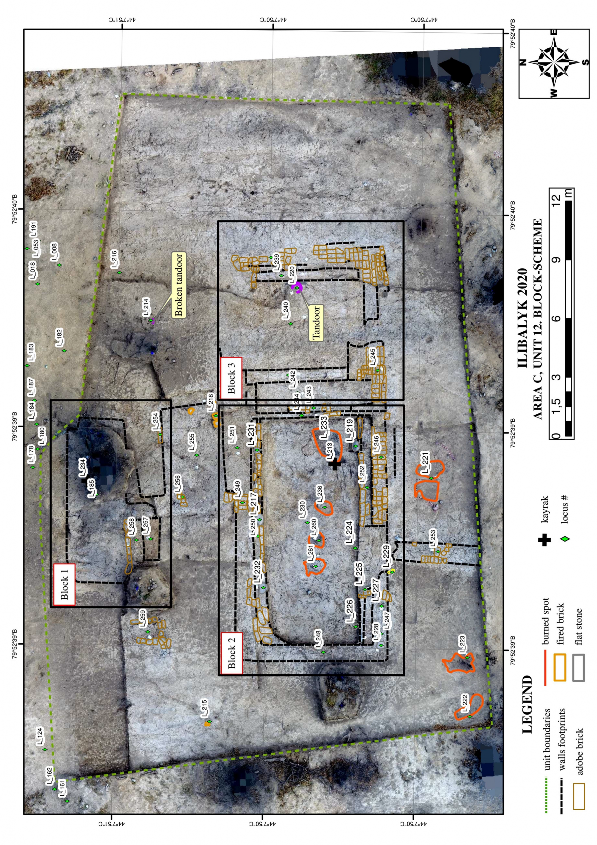

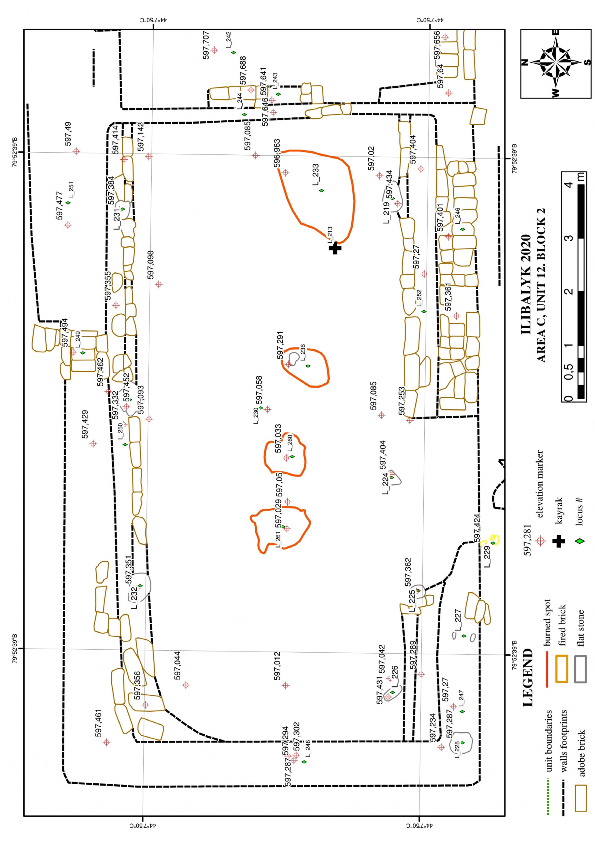

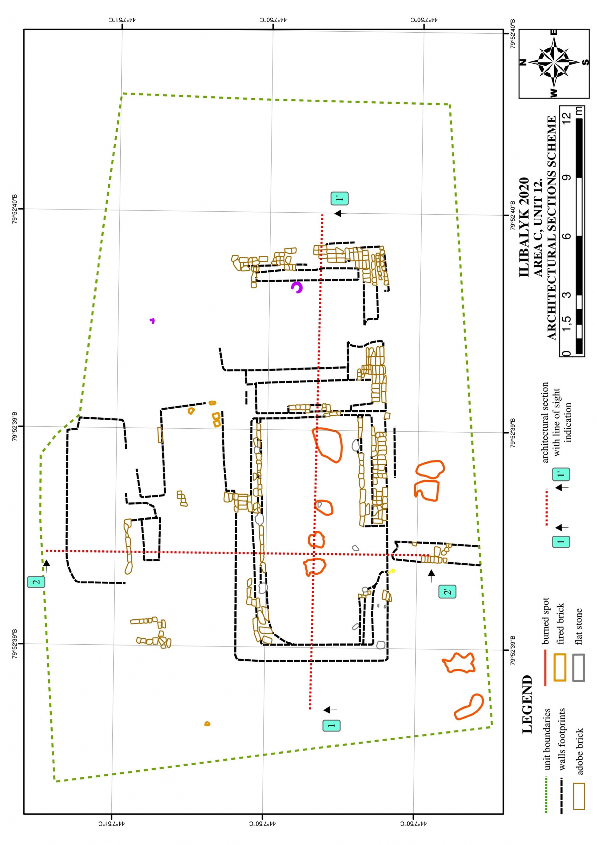

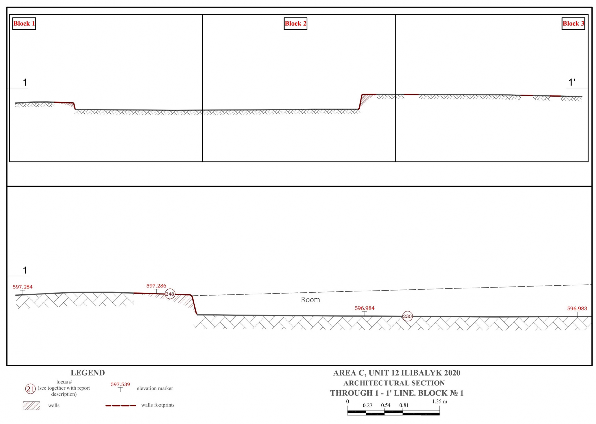

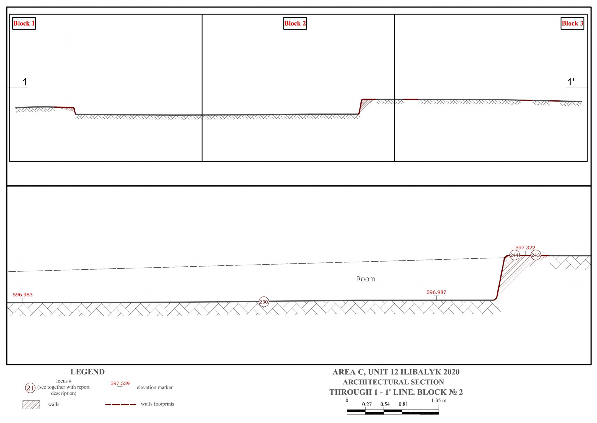

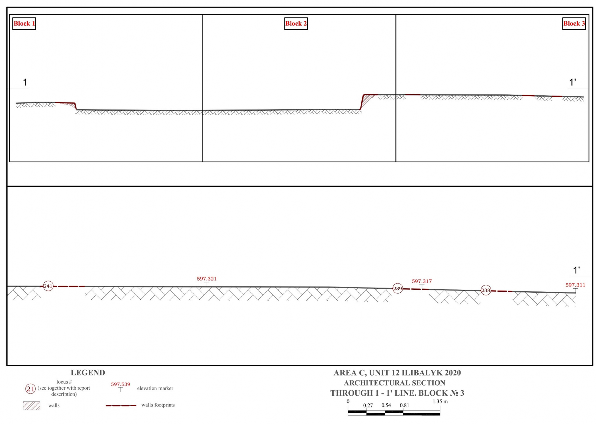

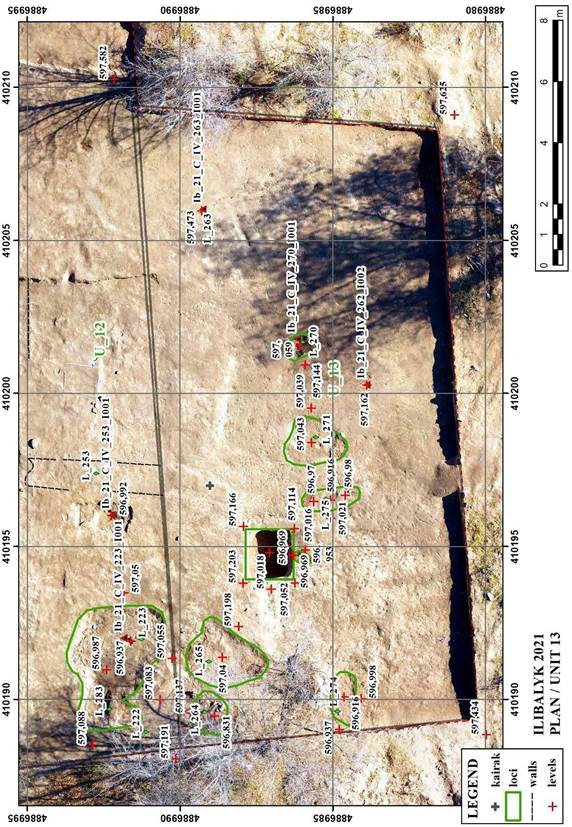

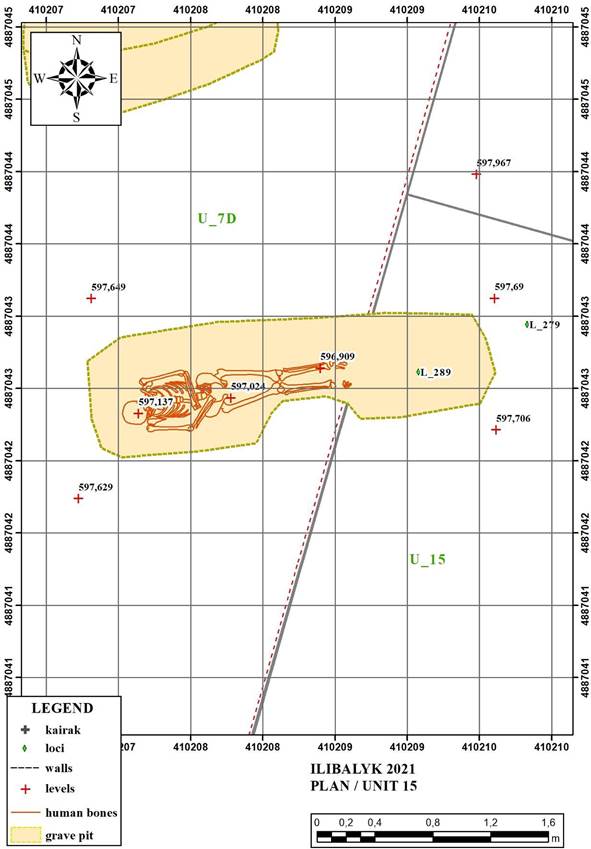

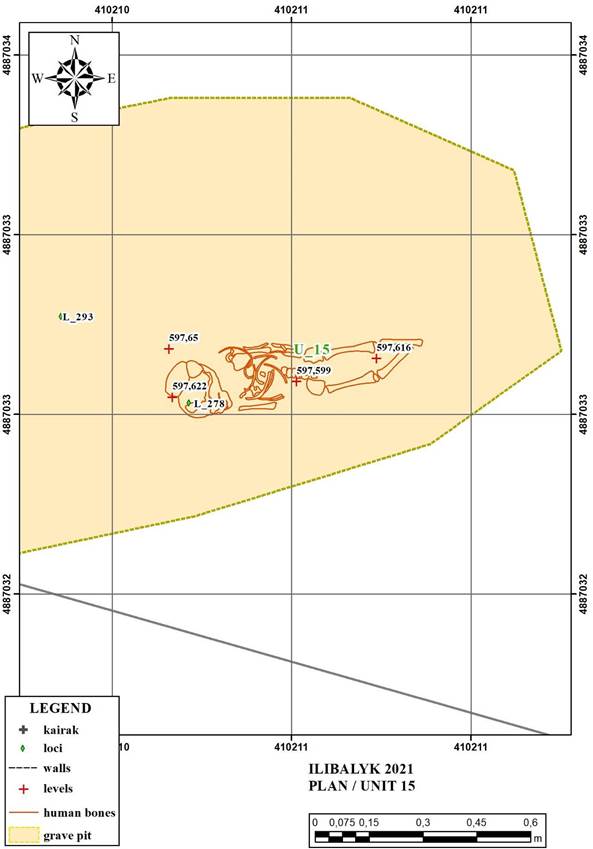

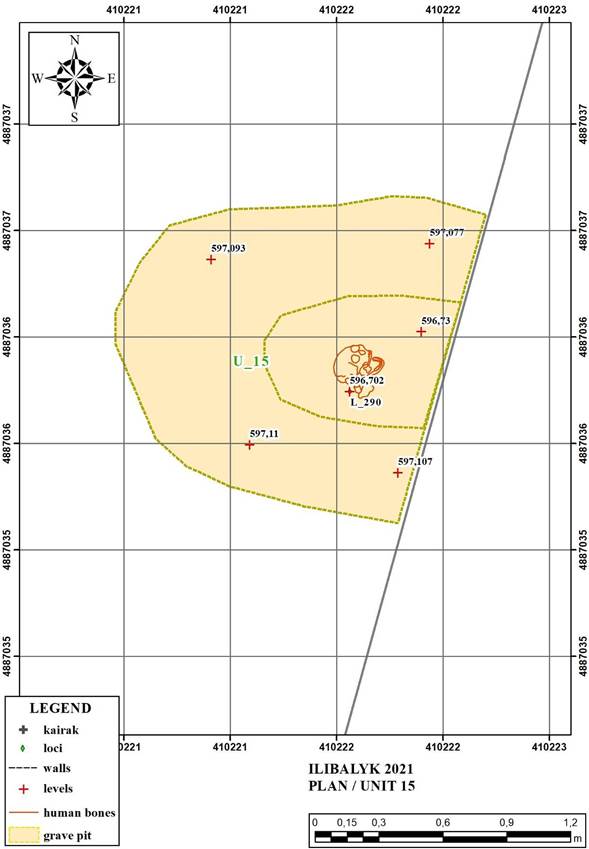

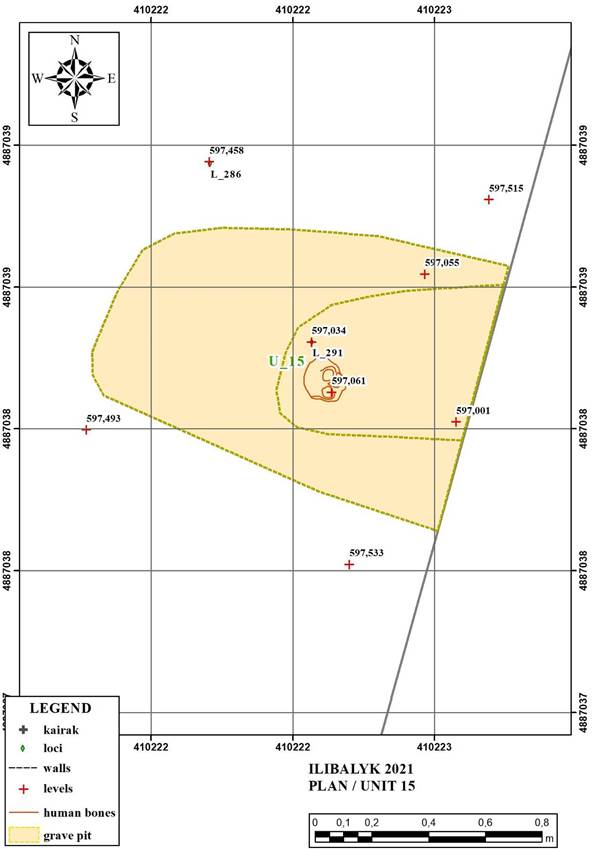

Unit 12 was delineated as rectangular in shape with the sides oriented along the north- south and west-east axis. The unit measured 22.5 m along the line from north to south and a width of 32 m along the west-east line. This made the total area approximately 660 m2. (See Appendix B, pgs 105-106-figs. 1-8).

Unit 12 is located within the vicinity of previously cultivated orchards on a small plane where dense, tall herbaceous vegetation of wormwood-type trees (Artemizia) grow together with low-growing shrubs. On the northern and southern sides of the excavation, wild fruit trees of the Elaeagnus commutate variety (silver oak) grow, as well as wild apricot trees belonging to the common apricot (Prunus armeniaca Lin., Armeniaca vulgaris Lam).

The site on which Unit 12 is located appears relatively flat and the topsoil layer consists of loamy soil types with a greater extent being a yellow loam of a dense structure. On the exposed areas of the surface, dusty loess deposits of a gray tint are visible.

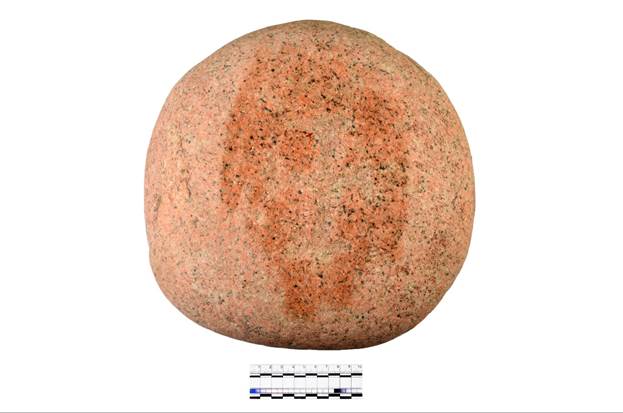

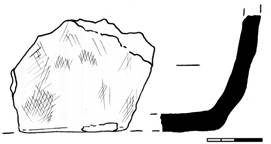

A large portion of Unit 12 was previously exposed in 2017 which removed the topsoil layer. One trench (5 x 5 m) was dug at that time (designated as Unit 2 at that time, but a subsequent unit in 2018 in Area C also received this designation) in this section which revealed a large stone (40х31х9) with hundreds of pick marks but with no discernable inscription or design as well as a pottery fragments and animal bone. (See 2017 dig report, pgs 107-116, 119- 120, 158). The unit revealed no graves or other features at that time. This is probably due to the fact that it is very close to the structure discovered that is explained below.

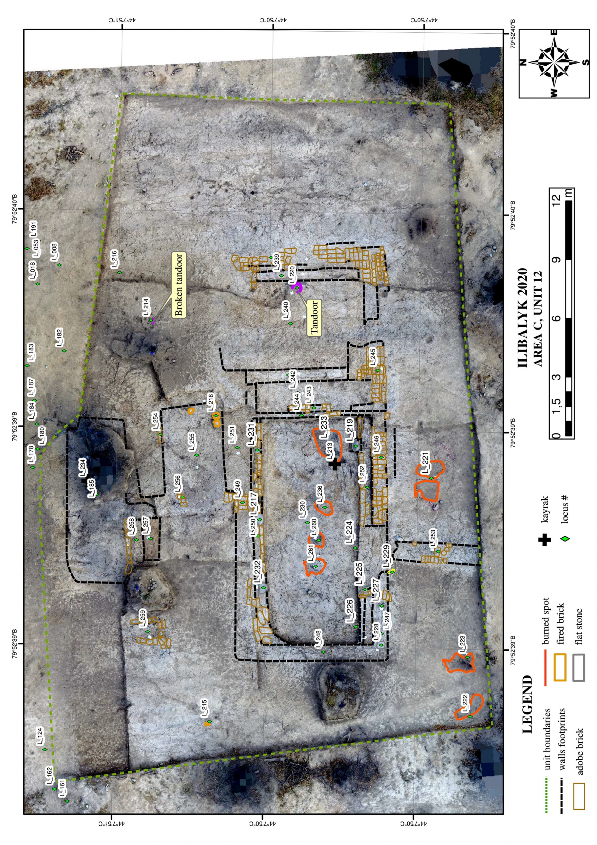

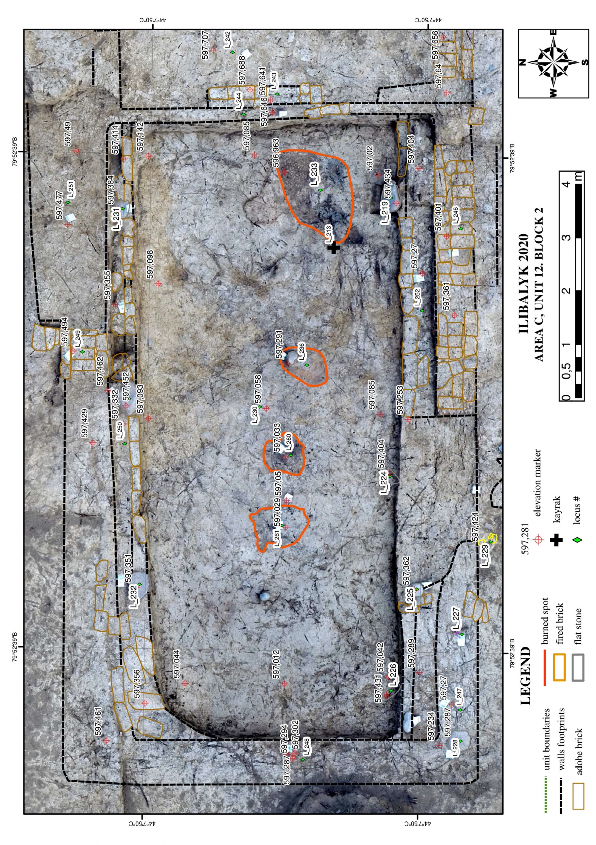

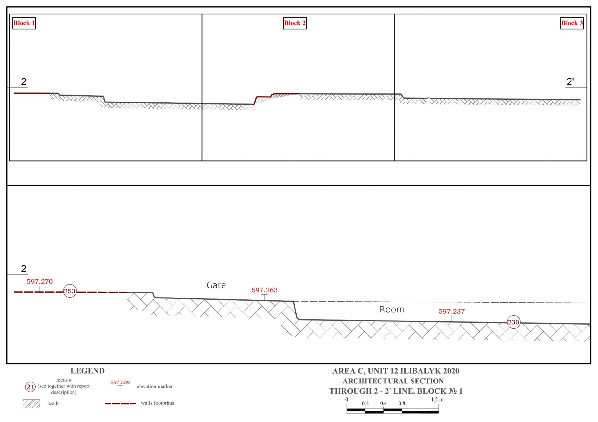

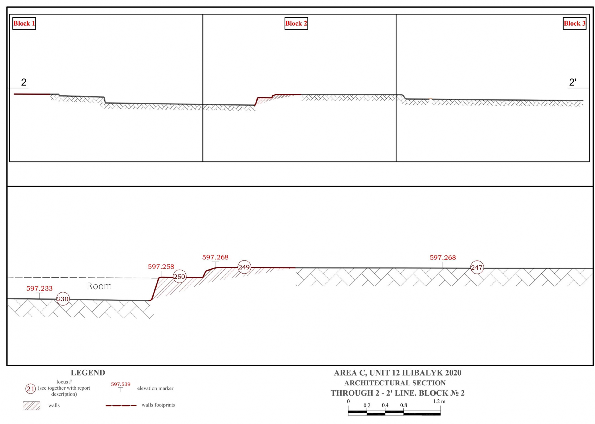

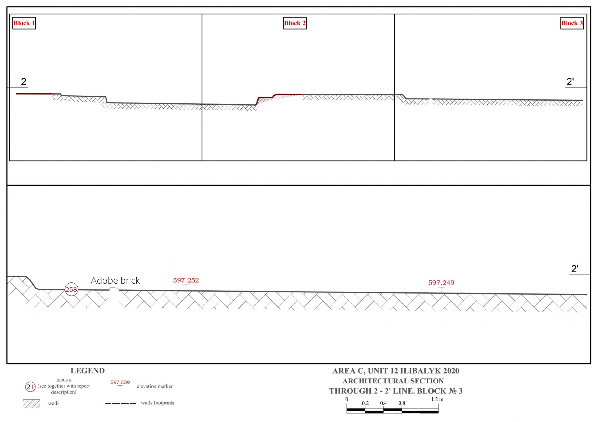

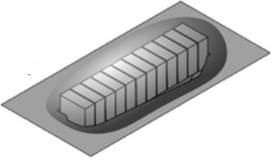

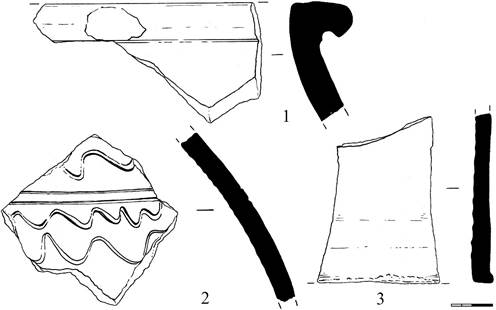

Excavations on this site revealed a rectangular building 21 x 8.7 meters in dimension with an east-to-west orientation.

The building consisted of three rooms and a possible courtyard:

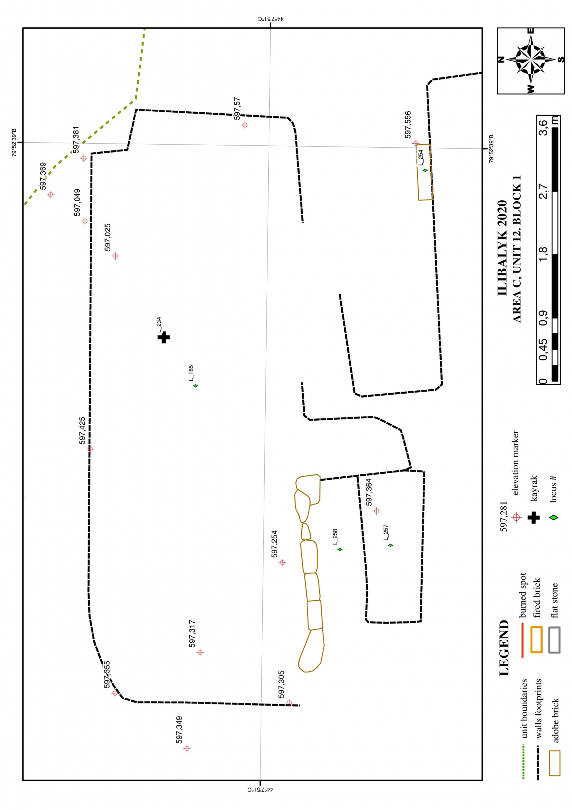

Room 1 was located in the western part of the building and occupied a majority of the structure. The dimensions of this room were 11.6 x 6 meters. Inside the room, from the northern and southern sides, along the walls, ledges made of adobe bricks were identified. The ledges were 60 cm wide and 40 cm high. Five flat, boulder-sized stones were found on these ledges with 3 on the northern ledge and 2 on the southern ledge. The stones were arranged parallel as though meant to face each other. It should be noted, however, that the stones were not perfectly opposite from one another. This may have been due to seismic activity, agricultural activity, shifting of the soil, or poor architecture. While further investigation will be necessary, it is probable that these stones served as bases for wooden pillars for the structure, though the building’s size probably did not require these pillars for support but may have supported features for an aesthetic purpose.

In the southeastern and northeastern part of the room, the walls had a 50 cm outward indentation. The length of the indentation was 4 meters, indicating a possible niche. A thick layer of clay plaster discovered on the inner side of the northern niche indicates that that the wall was visible to the original occupants.

In the center of the room’s southern wall, a gap of 2.5 meters was revealed. This gap may indicate the main entrance to the premises, particularly of Room 1.

A large amount of charcoal was found on the floor of the room, as well as within the soil fill. In center of the room on the floor, three spots of calcined clay were revealed which verifies the presence of burning.

It is apparent that this room contains a sunken floor 40 cm below the determined occupational surface.

Room 2 was located to the west of Room 1. This room was raised approximately 60 cm above the floor of Room 1. Rooms 1 and 2 were separated by a partition made of adobe blocks measuring 2.1 x 0.3 meters and located exactly in the center of the western edge of Room 2. The room itself measured 5.9 x 1.6 m. The northern wall of the room had not survived, but perhaps this wall contained an entrance. The floor level in Room 2 appears to correspond to the level of the ancient, occupational surface and measured at a level of 597.685 m. asl.

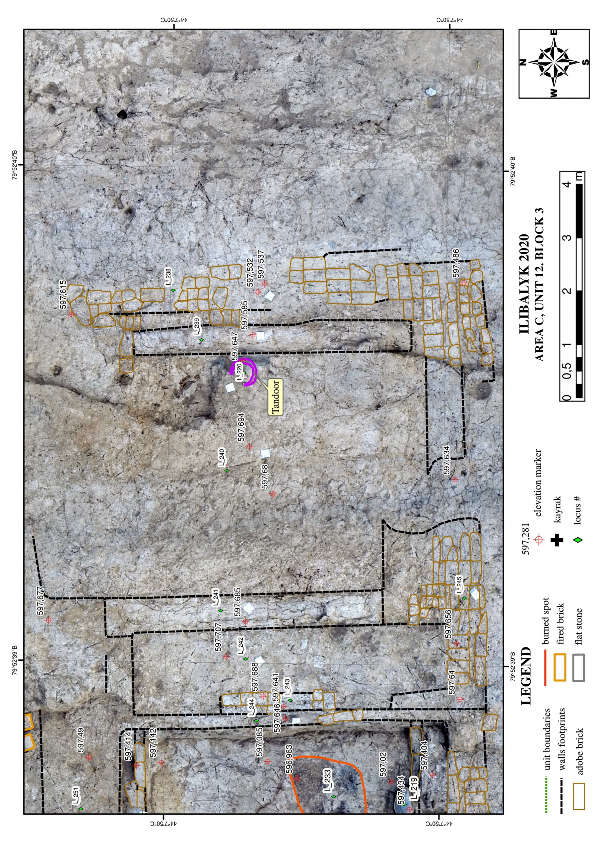

Room 3 was located in the eastern part of the building. The northern wall had survived only in the northwestern section as identified by traces of plaster. The western and eastern walls of the room differed from the rest of the walls of the building in that they were made of pakhsa (tamped earth) fill, while the rest of the walls were made of adobe blocks. A tandoor (furnace) was located at the edge of the western wall of Room 3. The room’s dimensions were 4.5 x 7.4 meters and extended in a north-south direction.

To the north of Room 1, outside the building, an adjoining area made of tamped, gray soil interspersed with charcoal was exposed. It was not possible to determine the full configuration of this feature, but presumably it represented two rectangular sections connected by a corridor. On the perimeter of this feature, traces of plaster and a course of adobe blocks were found in certain sections. In the southeastern part of this feature, in the corner, 4 square- shaped, fired bricks were revealed and were possibly the remains of the entrance to Room 2.

To the south of Room 1, opposite the supposed entrance, the remains of adobe brickwork were found which formed a one-meter-wide platform which extended in a north-south direction. It is assumed that this feature could be a pedestrian pavement leading to a southern entrance for Room 1.

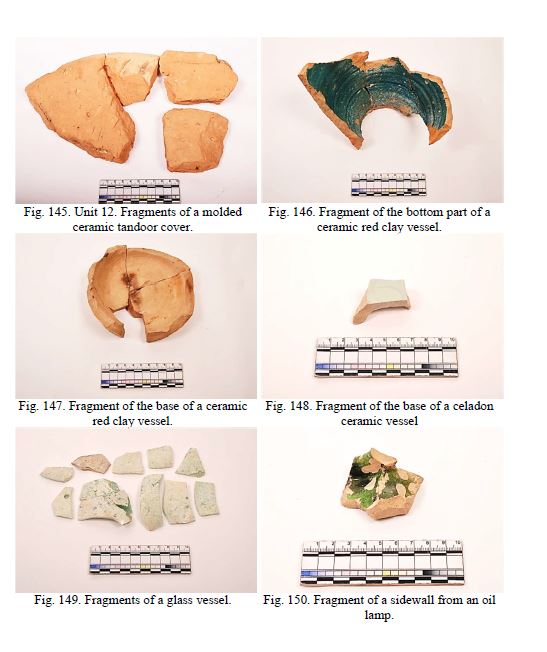

The excavations revealed some interesting artifacts:

-

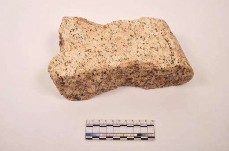

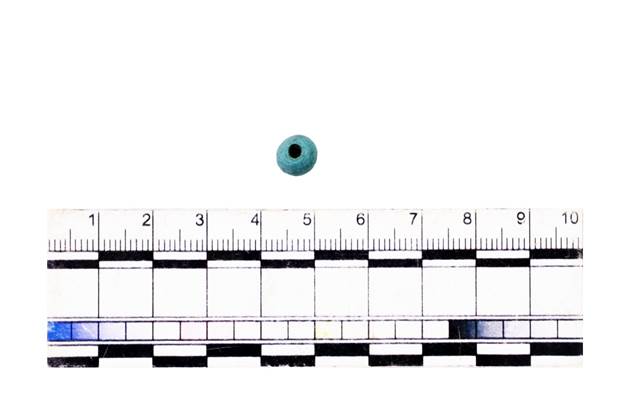

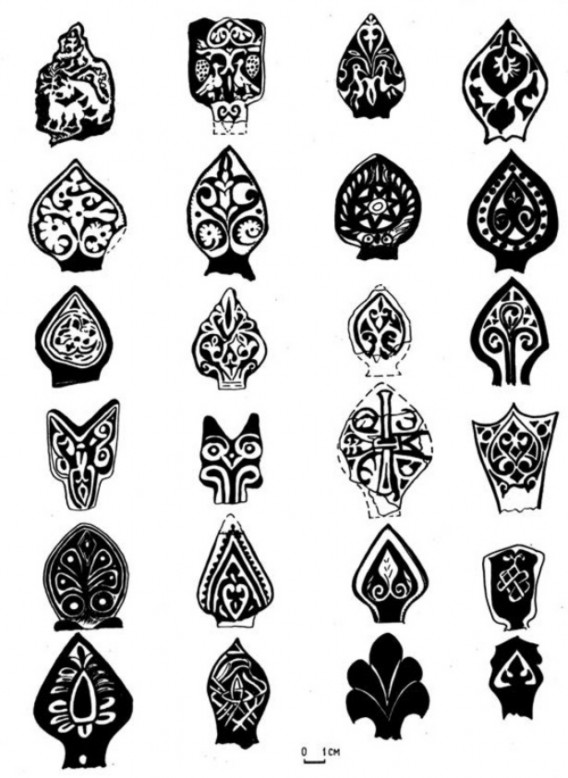

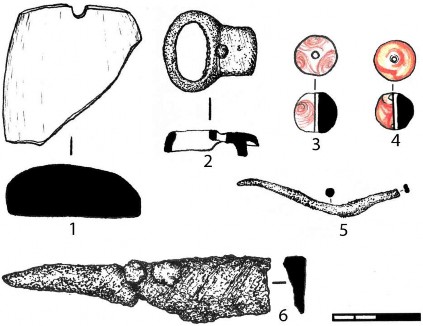

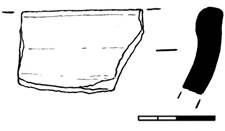

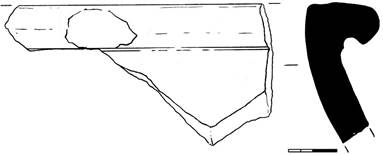

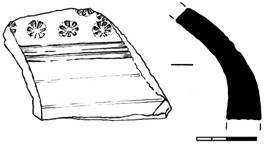

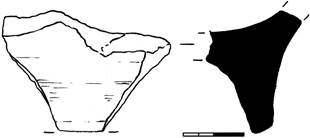

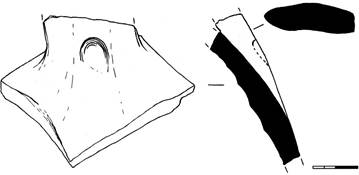

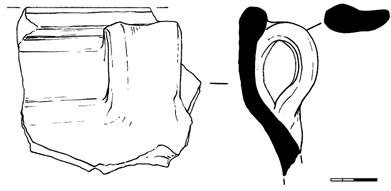

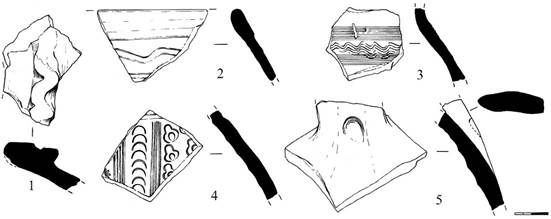

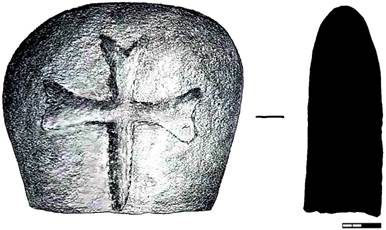

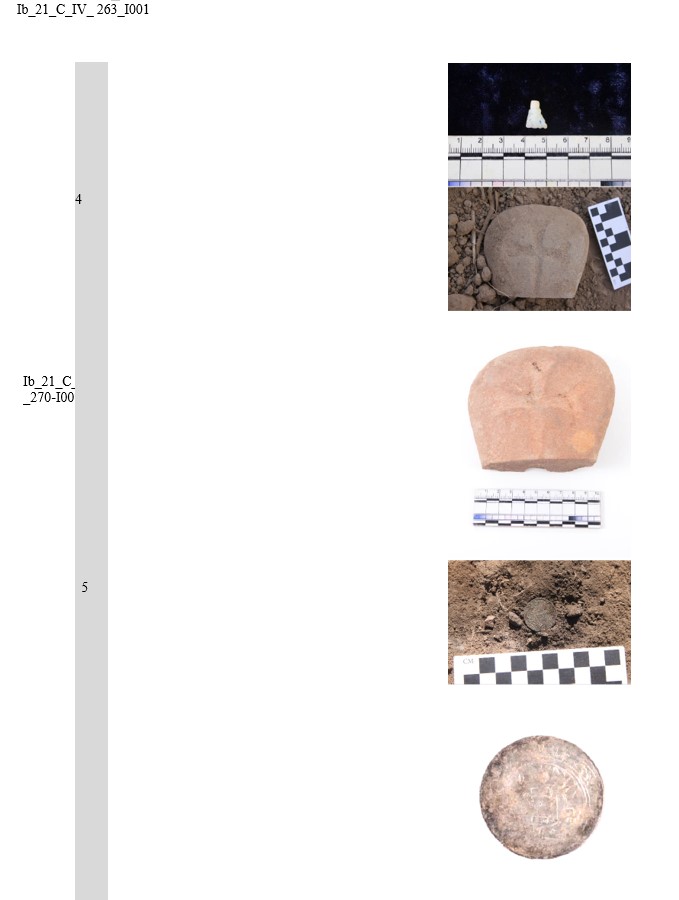

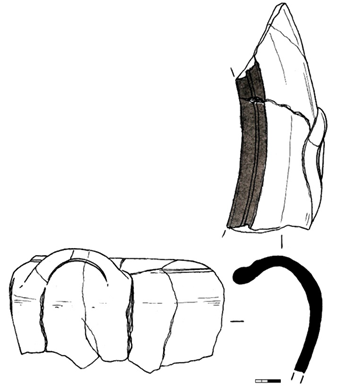

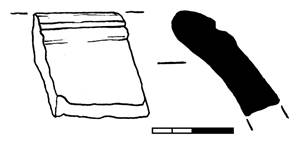

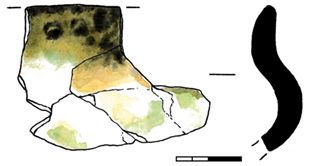

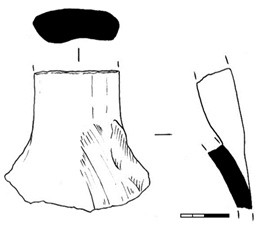

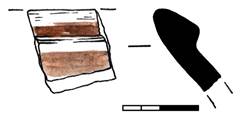

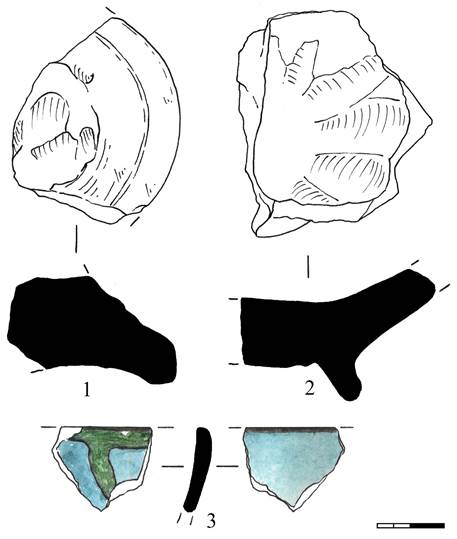

In Room 1, in the upper layer, a granite kayrak (gravestone) was found which measured 20 x 11.4 x 7 cm. It is uncertain as to whether this stone is in situ due to the fact that the topsoil layer had been previously disturbed and backfilled by mechanical means in 2017. (L-213, Serial no. Ib_20_С_IV_213, see pgs. 50,107,132-Fig. 165).

-

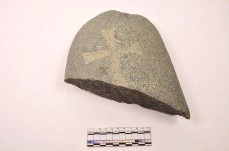

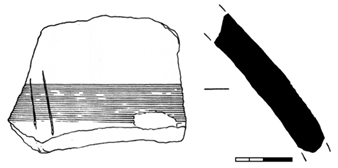

In the northern part of the unit, in the area of the possible courtyard (L-185), a second kayrak (gravestone, L-234) was discovered which measured 23 x18.5 x 7 cm. Currently, no grave is in association with this stone which may be due to the fact that a cluster of small fruit trees is obstructing a possible grave. During the 2019 excavations, a small metal cross was discovered less than 1 meter from this gravestone.

-

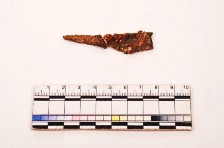

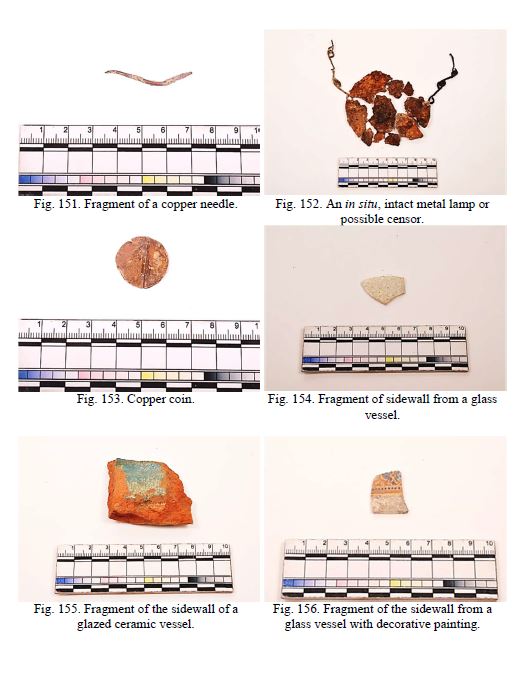

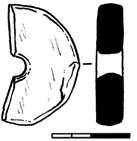

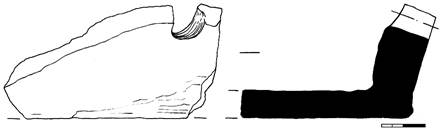

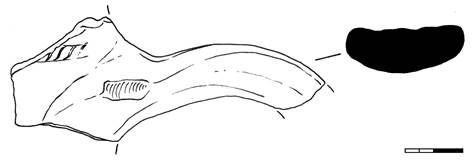

A metal artifact was found in the eastern section of the unit, located outside the eastern outer wall of the structure by less than 2 meters. This highly fragmented and corroded artifact has a concave, saucer-shape and along the edges on both sides there is a through hole for a copper chain. It was possibly intended to be a lamp or a censer (Serial no. Ib_20_С_IV_212_I005. See pgs. 55-56;130-fig. 152).

-

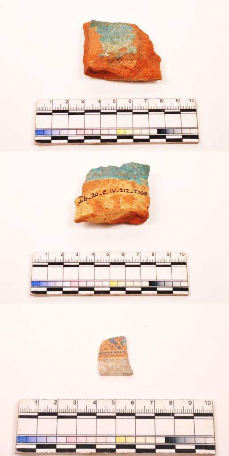

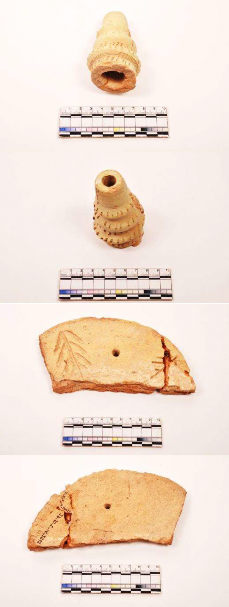

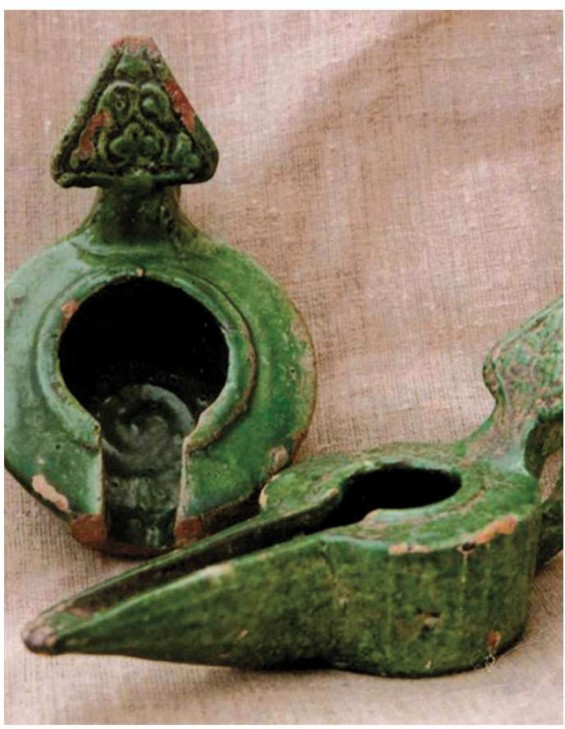

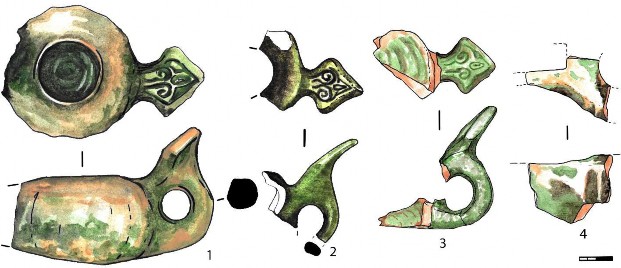

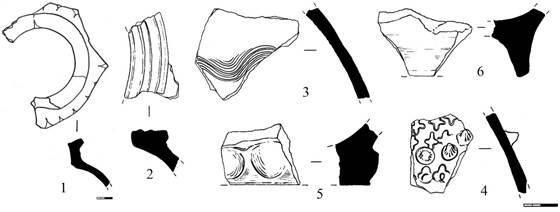

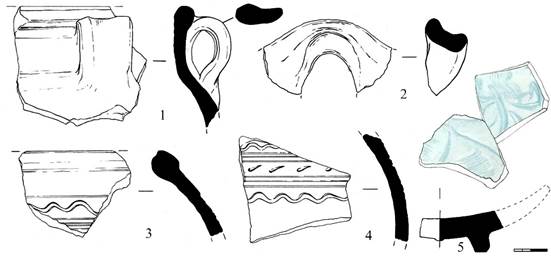

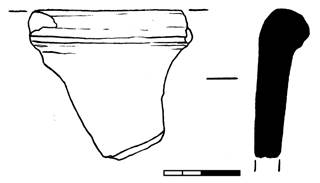

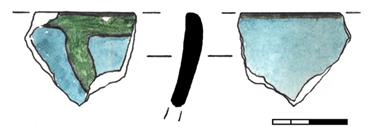

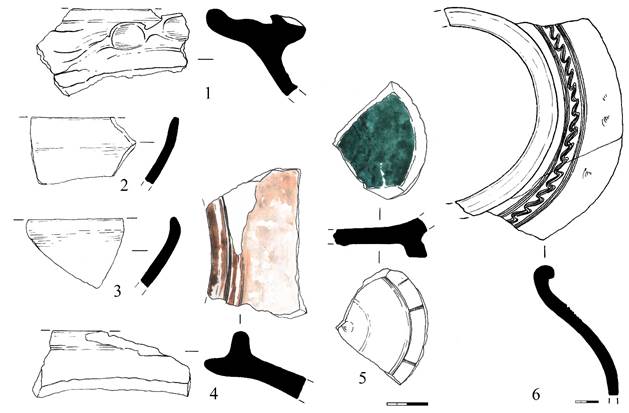

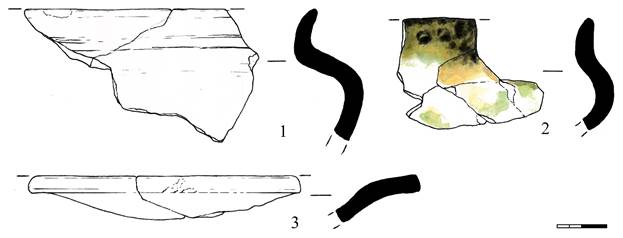

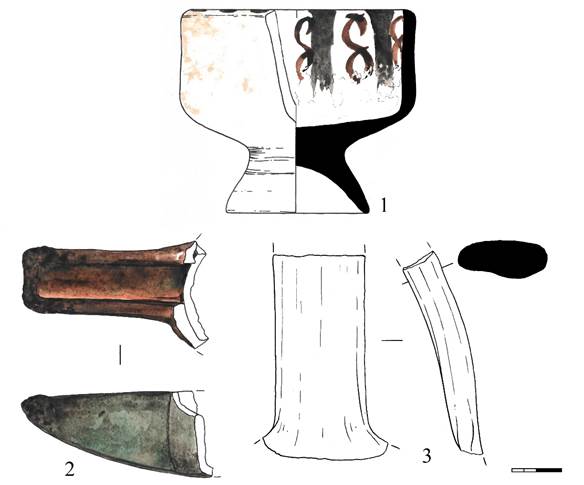

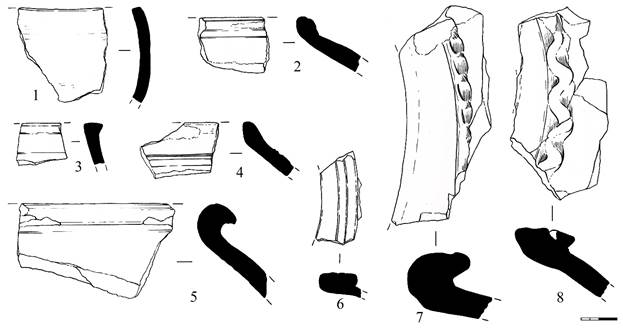

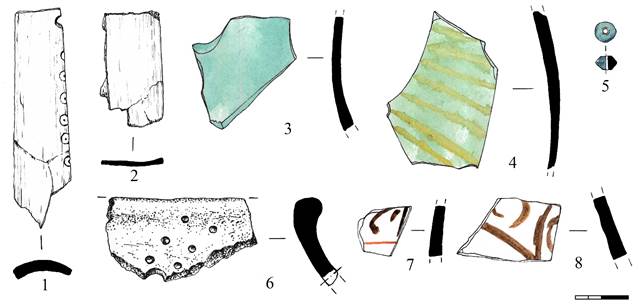

In Rooms 1 and 2, fragments of oil lamps; vessel potsherds with a brilliant, blue glaze; and the capital of a candlestick were found which indicate high-status finds (Serial no. Ib_20_C_IV_212_I001, I009, I015; Ib_20_C_IV_230_I001. See pgs 57-60; 129-fig. 150; 131- fig. 160; 132-fig. 163)

-

In Room 1, at floor level, a painted glass vessel fragment was found (Serial no. Ib_20_C_IV 212_I10. See pgs.71-72; 130-fig. 156). This comes from a high-status vessel, likely an import, which could be associated with an ecclesiastical function given the context.

1.2 Unit 12 Loci Descriptions

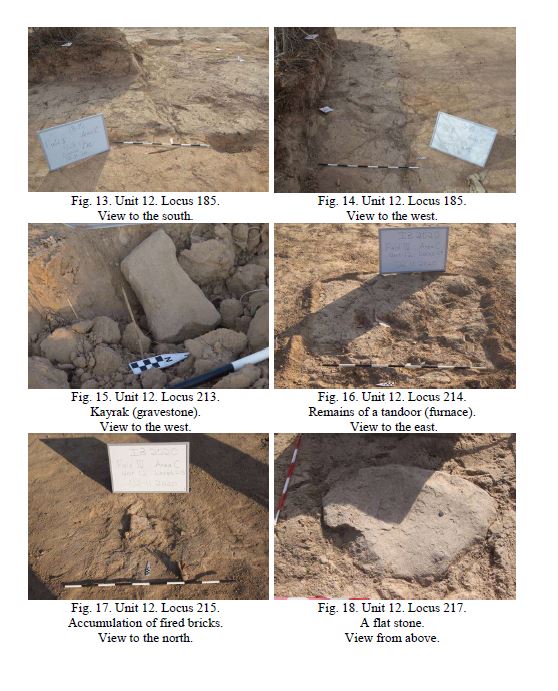

Locus 185. A hardened, ash-colored area. This dense area with gray-colored soil measured 3 x 8.35 m, encompassing an area of 25.05 m2 and was located to the north of the structure found in U-12, partially within the boundaries of the 2019 excavation site between Units 9C and 9B. The UTM coordinates measured at x: 410199.401; y: 4887011.713; and 597.425 m asl.; x: 410203.536; y: 4887011.803; and 597.381 m asl.; x: 410195.933; y:

4887011.361; and 597.355 m asl.

Originally, it was thought this feature was a grave that was obscured in the soil as it lay in the baulk of the southern-most boundary of Area C during the previous season. It was then designated Locus 185. Excavators determined to examine this locus in order to show a potential relationship with the structure in U-12. This locus as originally revealed lay within U-9C on the border with U-3 and within the northern baulk of U-12. It is also the location where a bronze metal cross was found that was thought to possibly be attached to a wooden coffin. Thus, the rationale was that it could have been a high-status grave, in addition it was between 5-6 meter from the northern wall which was detected from the structure previously revealed in U-12.

The excavation was complicated in that only part of what was considered to be the grave pit was revealed as is lay under a tree. Care was taken to prevent damaging the tree. The section of the baulk of U-12 in the border with U-9C was gradually leveled. One hundred percent of the soil was sifted. Pottery fragments and animal bone were revealed, mostly in the topsoil layer. The feature contained a dense, light gray loam which was laid out in a west-to-east direction with a slight depression.

The excavation fill, which included topsoil material, continued to reveal a significant amount of pottery including a large fragment of blue glazed pottery. Burning and charcoal flecks continued to be found just below the topsoil layer. Despite attempts, a southern boundary for a grave could not be found. As soil was lowered in this southern section, some animal bone fragments were found and carefully examined. However, as the area was cleared with a mechanical blower, the gray soils which were thought to define a grave pit actually extended much further west than anticipated. Thus, it no longer appeared to be a grave, eventually expanding to the above-mentioned area. Further soil that made up the “island” of the trees was removed in the western section. While clearing this section a kayrak (gravestone) was found and a new locus was opened, L-234 (see locus description below).

On the south side, the layout was cut by a feature of mud bricks and loam (designated Locus 258), as well as by a square feature of gray mud blocks (designated Locus 259) of an unknown, functional purpose. As further revealed to the west, the feature had a gradual rise. The western edge of the feature curved to the south. A thick, loamy gray coating 6-7 cm thick could be detected throughout this feature. While clearing the paved loamy area, charcoal and charred wood of various diameters and sizes were detected throughout the feature. While an interpretation is tentative, this locus may have incorporated a courtyard but may have also been enclosed due to evidence of plaster on the northwest side and later subject to intense burning, as evidenced by the charcoal throughout the feature. Further investigation is needed.

Locus 212. Opening layer designation of Unit 12. This locus lay south of Unit 3 (excavations in 2019) of Area C in a north-south, east-west direction. The opening excavation area dimensions: north to south 30 m; east to west 21.52 m. The total area of the excavation was 645.6 m2.

The rationale for choosing this area was due to previous kayrak finds from 2016 and also because it was in the area in which a metal cross was found in the southern baulk of what at the time with the furthest limit of our excavations at lower depths as defined in 2019 (see above L-185).

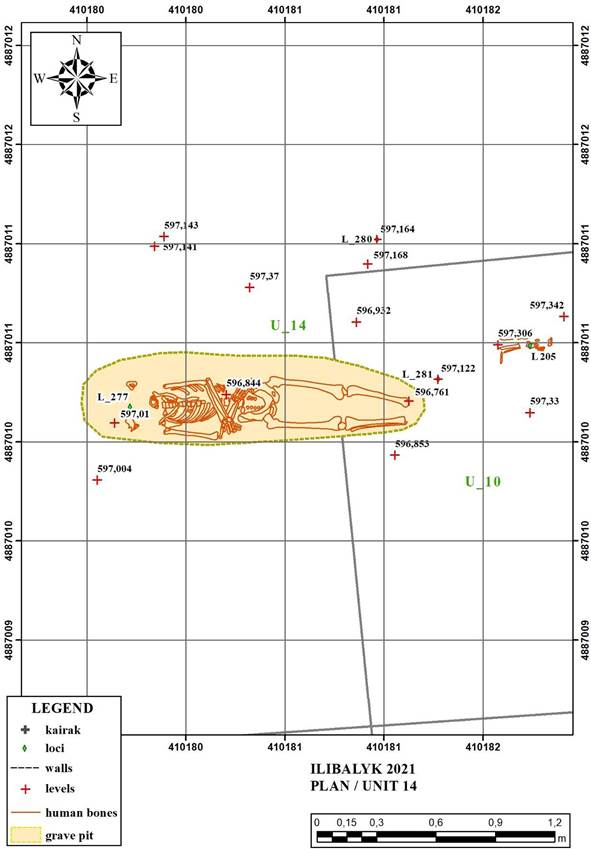

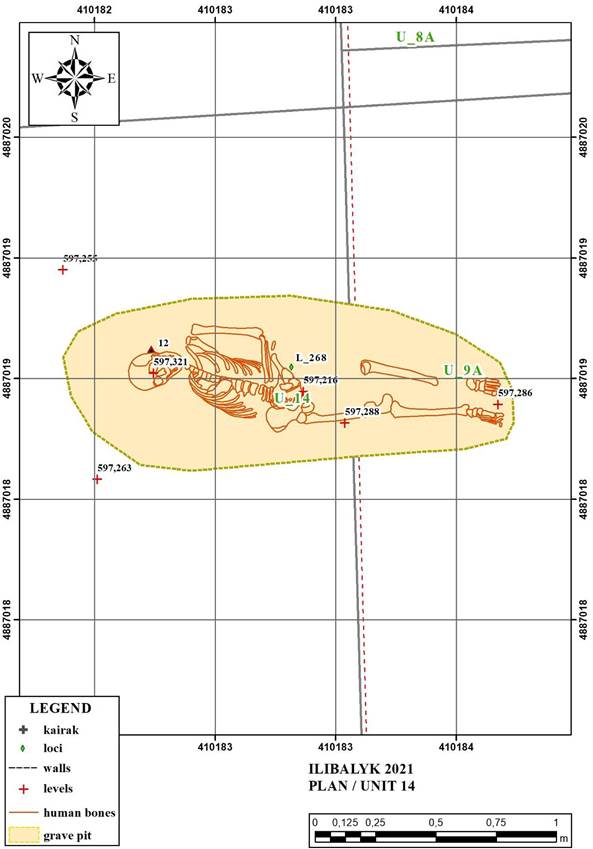

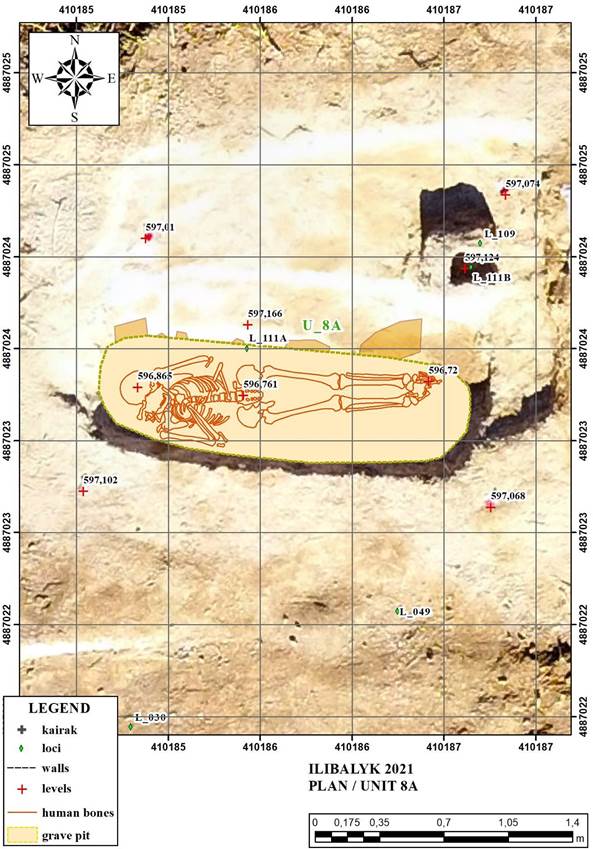

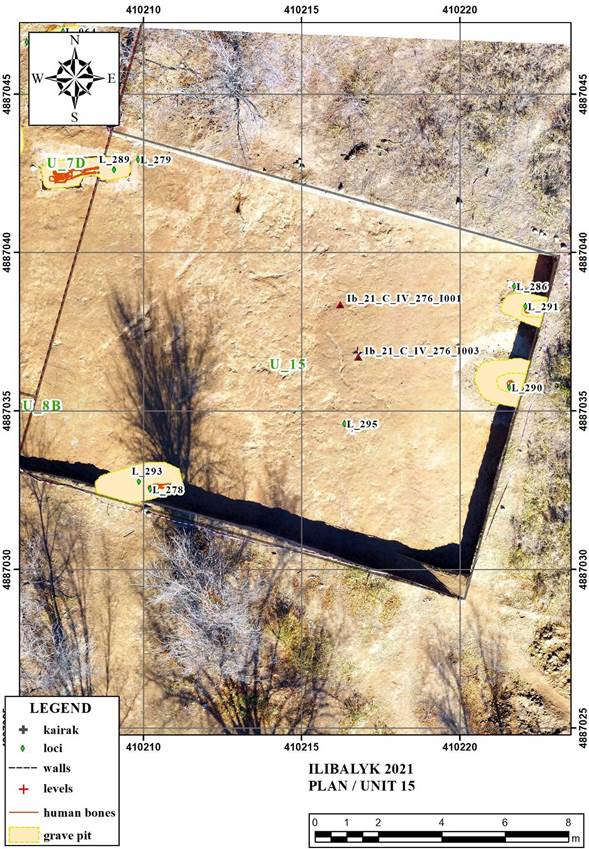

While a test trench (U-10) dug in 2019 extended from the southwest corner of Area C by approximately 45 m, human remains were located no further than 20 meters south, possibly indicating that the southern extent of the cemetery does not exceed beyond that point, which would be consistent with the gravestone (kayrak) finds to date which have not been discovered beyond that southern point. Excavators considered that further excavations in this newly designated locus, could potentially reveal elite, or high-status, graves as well as conclusively determine the southern boundary of the Christian cemetery.

The excavation level was an uneven surface and from east to west toward the center there was a noticeable depression, which then developed into a small, uneven rise to the west. The area was densely overgrown with small bushes and grass. Trees (elm) grew on the northern

and western sides varying from 3 to 5 m in height. The abovementioned vegetation had a dense root system of various depths throughout the layer. The soil was a yellow loam with loess content. The topsoil had been previously disturbed by mechanical means due to a large portion of this section that was cleared in 2017.

Excavations began from the north side proceeding to the south. Clearing was carried out to the depth of a shovel blade of approximately 30 cmbs. The density of the soil differed considerably in the northern and northwestern sections of the locus in contrast to the eastern corner of the excavation due, in part, to the root system of trees and grass. Fragments of ceramics and pebbles of various sizes were detected across the surface.

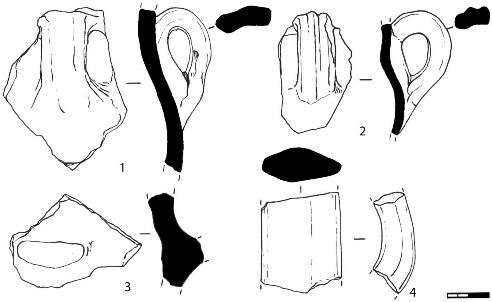

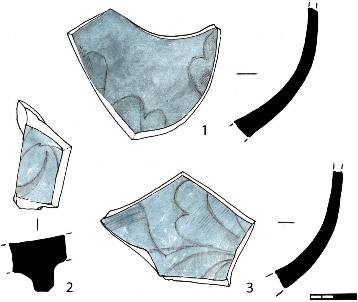

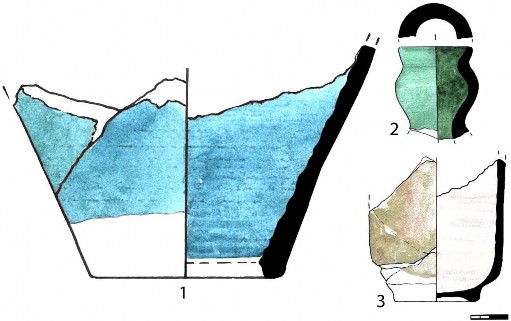

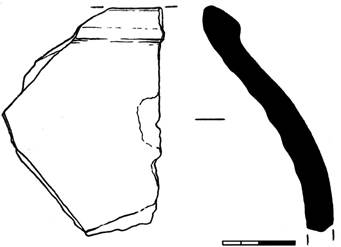

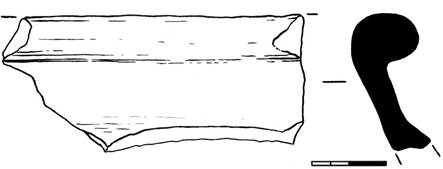

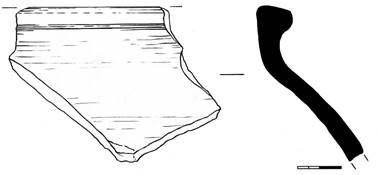

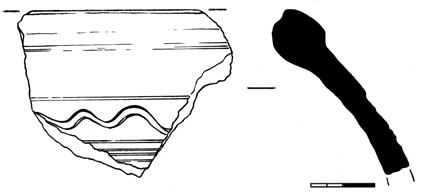

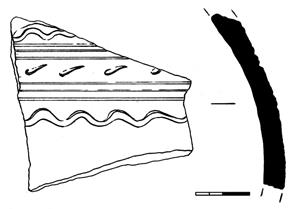

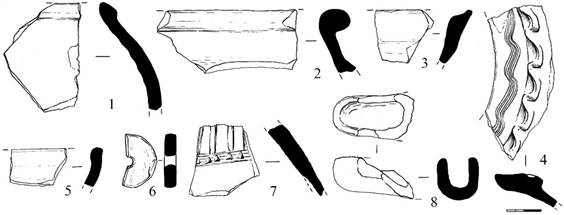

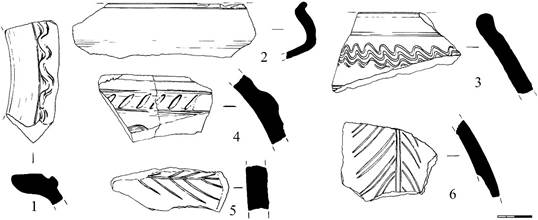

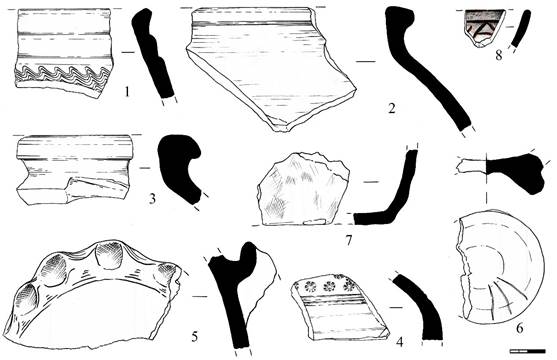

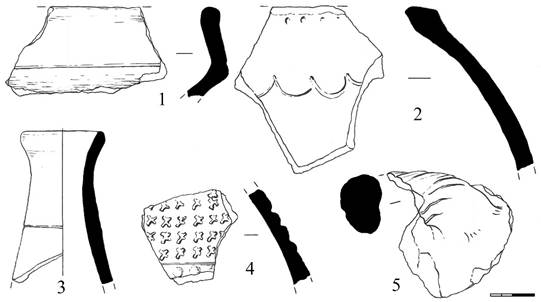

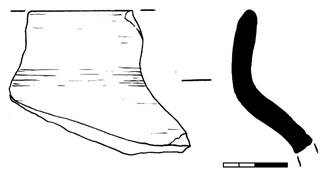

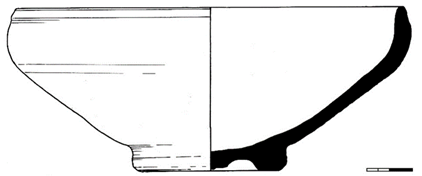

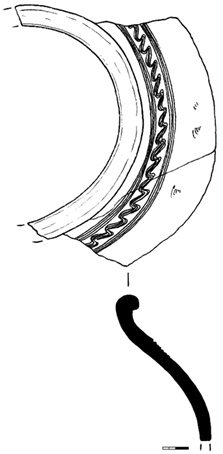

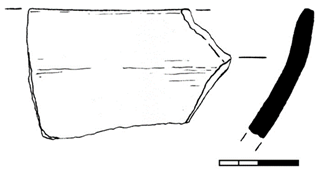

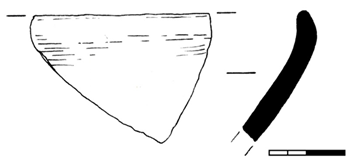

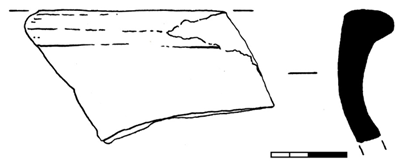

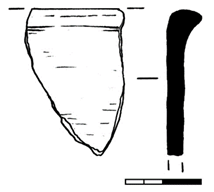

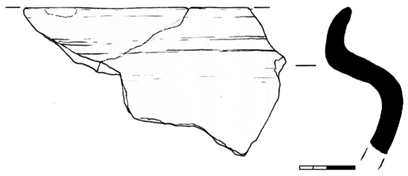

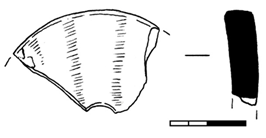

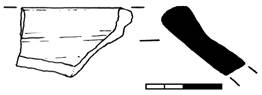

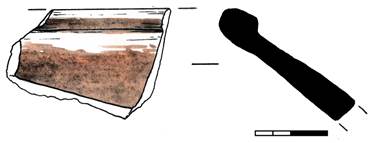

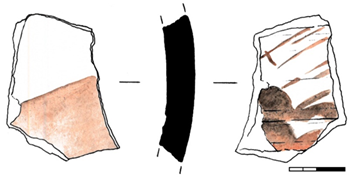

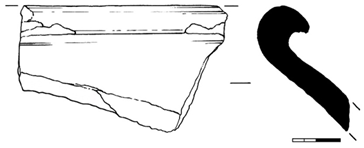

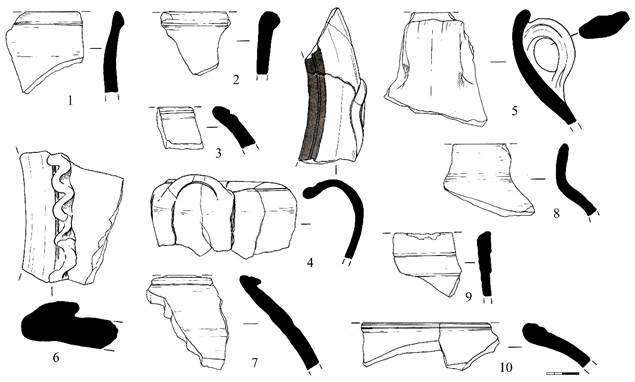

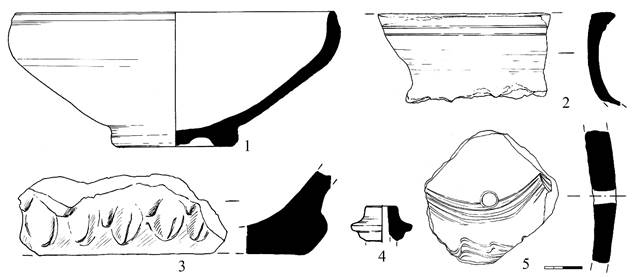

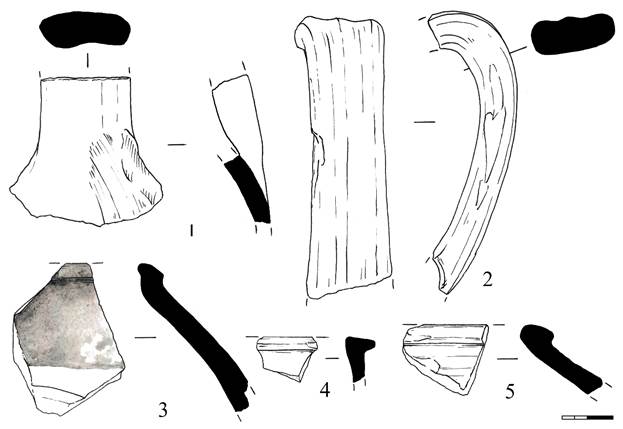

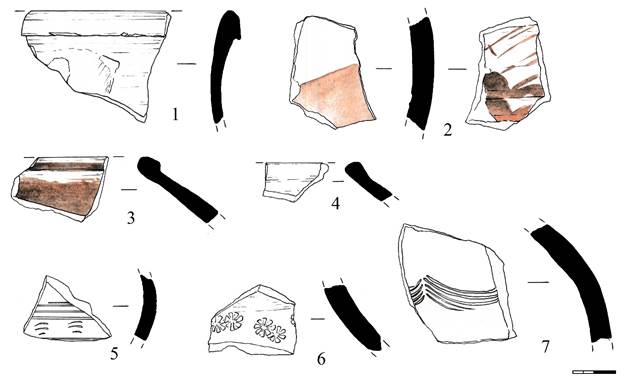

The soil in this northern section of the locus was gray and dense with an abundance of roots from the trees, as well as the densely overgrown grass. In this 30 cm level, fragments of thick-walled and thin-walled wheel-thrown pottery were found belonging to water jugs and pithoid-type storage vessels. Along with wheel-thrown ceramics, two portions of glazed, fineware vessels were found. One fragment, the lower half of a glazed bowl with a partially preserved circular base and covered with a turquoise and transparent, glass glaze was found.

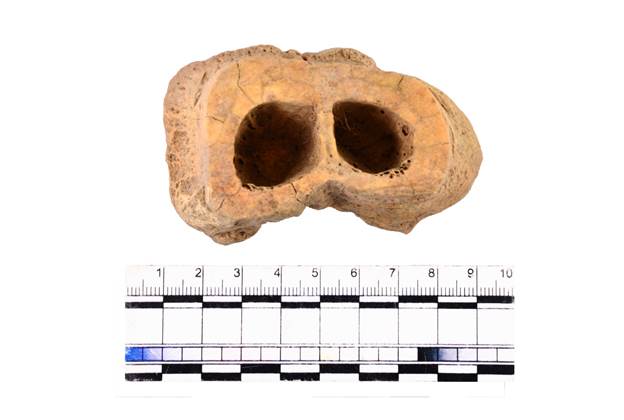

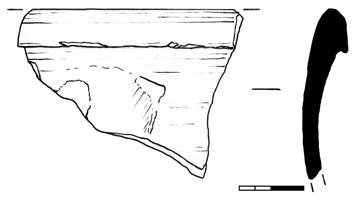

The second fragment belonged to a partially preserved, glazed oil lamp. It included a reservoir base with handle. The fragment was covered inside and out with a green pigment and a transparent glaze.

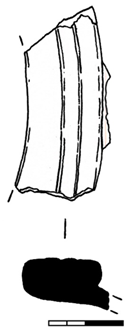

Fragments of fired bricks were also found among the potsherds of wheel-thrown ceramics. A tamga (tribal or manufacturer’s) stamp was discovered on one of the bricks. Along with ceramics, the excavated layer contained fragments of sheep and cattle bones.

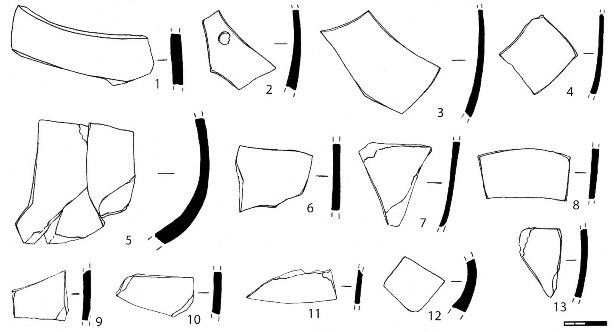

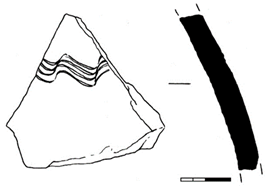

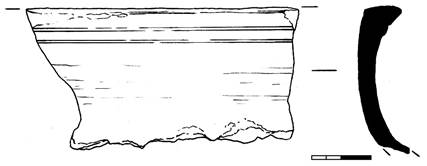

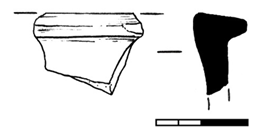

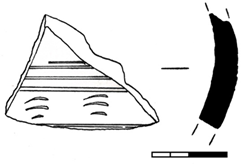

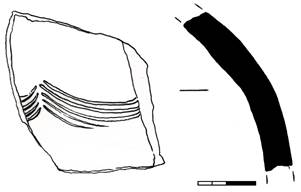

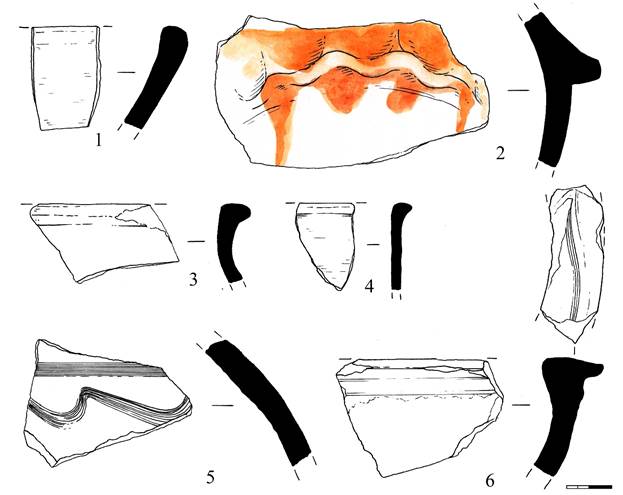

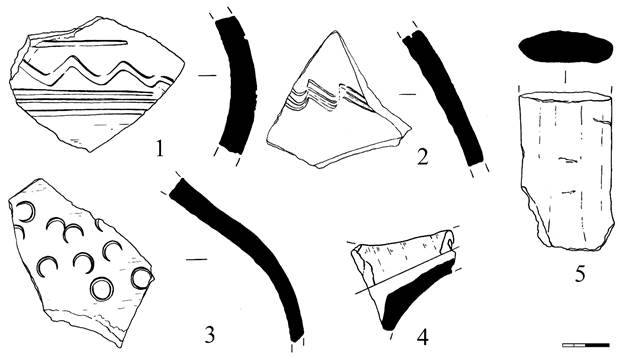

The pottery in this section of the unit was represented by fragments of thick-walled and thin-walled vessels. Of special note was a rim fragment of a wide-necked water jug and the rim and sidewall of a thick-walled jug. Soot and traces of exposure to fire was found on some of the pottery sherds. These pottery fragments included those belonging to tableware (pots and cauldrons).

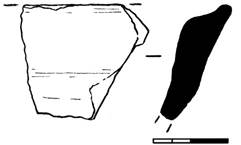

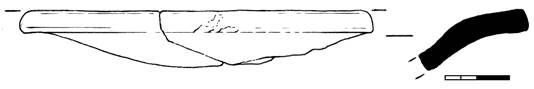

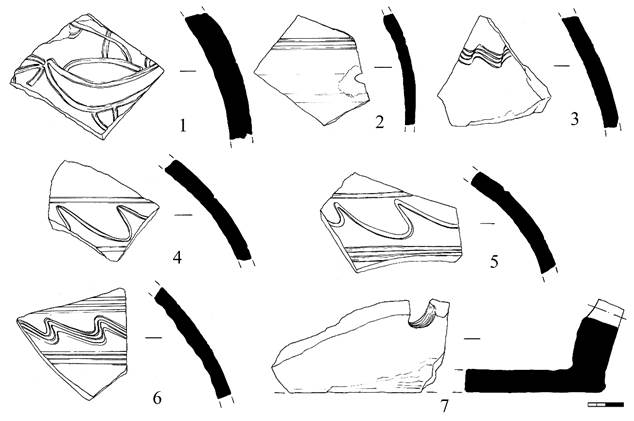

Among the significant number of glazed ceramics were three fragments of high-status pottery from a bowl (or cup) which were covered on both sides with a light-turquoise paint and transparent glaze. The fabric from these fragments appeared to be celadon with absolutely no inclusions. Its fine quality indicates that it was a probable import (See section 5.4, pgs. 70-71; 131).

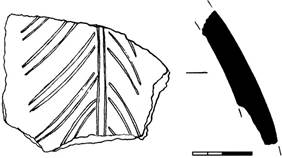

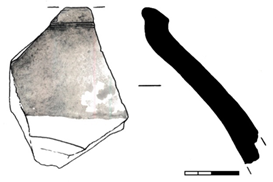

Also, of special note, was the discovery of a fragment of black-burnished pottery from a thin-walled cup. The fragment was covered with a black slip on both sides and smoothed, or burnished, prior to firing.

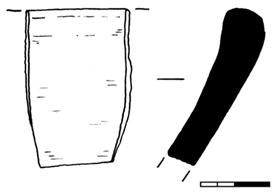

As soil removal continued along the central section and western edge of the locus, along with fragments of wheel-thrown ceramics, the rim of a large pot; the walls of a water jug; as well as a fragment of the spout of a narrow-necked jug were revealed. Fragments of the lower wall and the base from water-bearing jugs and storage jars were detected in the layer.

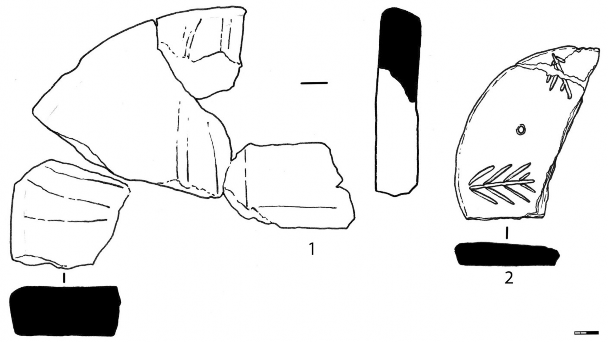

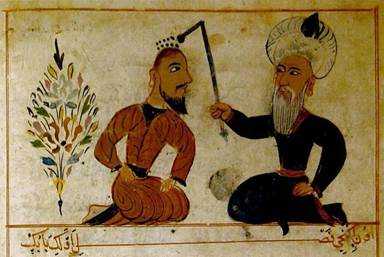

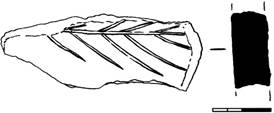

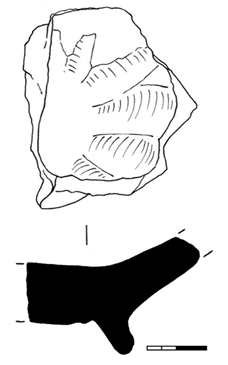

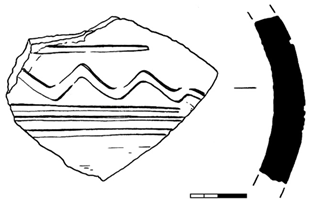

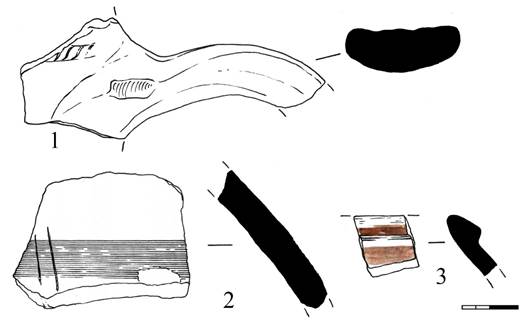

The fragment of a tandoor (furnace/oven) cover was found in the northern part of the unit. The smoothed side of the cover contained an inscribed image of what appears to be a

evergreen tree. A similar tree-type inscription is found on vessels from a similar time period (13th – 15th centuries) on vessels at Otrar (See Akishev, et. al, 163).

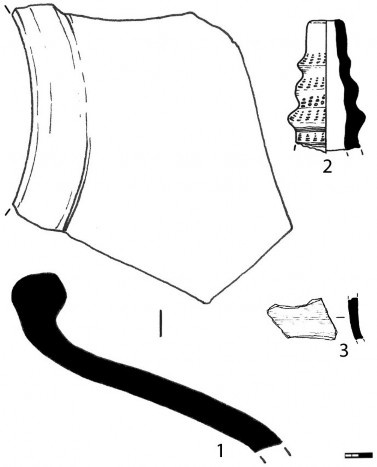

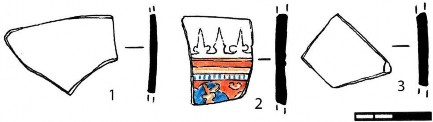

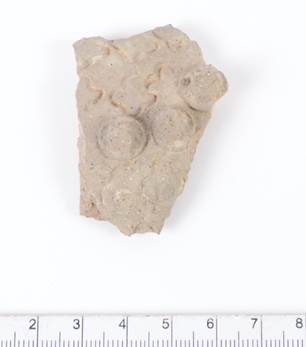

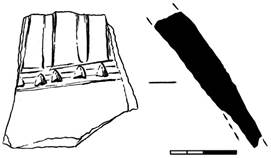

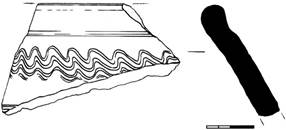

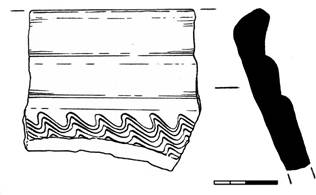

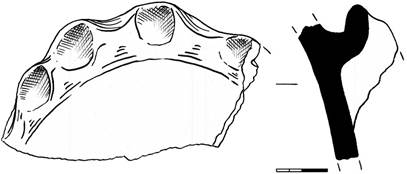

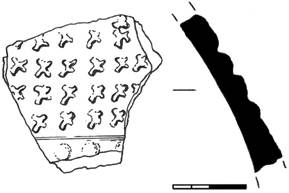

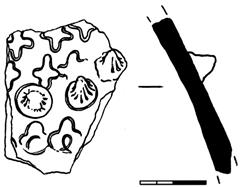

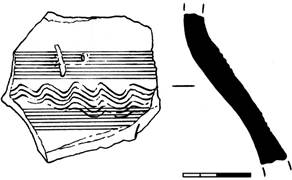

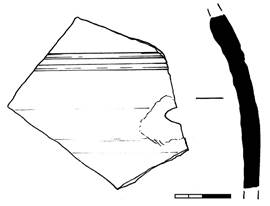

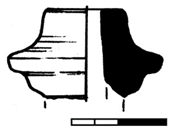

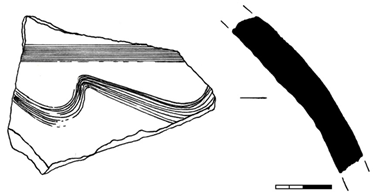

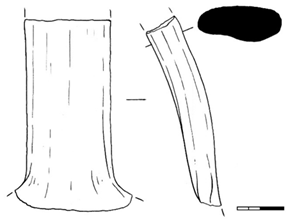

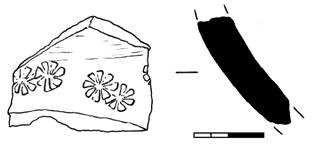

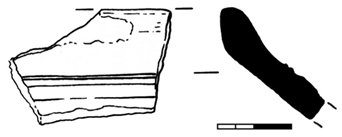

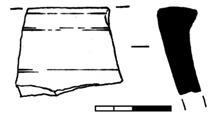

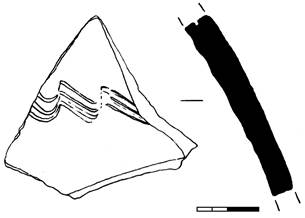

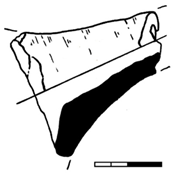

Among the glazed ceramics, one find included another oil lamp covered with a green glaze. At a different depth, a partially preserved fragment of an oil lamp with a faceted reservoir was discovered. Its top was attached to a loop-shaped handle with a triangular thumb rest whose surface was decorated with stamped floral ornament with what could be interpreted as being in a cruciform shape. Similar lamps are found in the layers of the 13th-14th centuries in ancient settlements on the territory of Zhetisu (Semirechye) and southern Kazakhstan, but not with this particular thumb rest design. (See section 5.3, pgs. 57-69 for further discussion).

Additional pottery found in the locus included sidewall fragments from a water jug with a drill hole in the lower section just above the base which probably served as a water spout. This layer also contained sidewall fragments from tableware such as pots and cauldrons. In addition, fragments of loop-shaped and knob handles from storage jars and jugs were found.

Glazed ceramics also included blue-glazed fragments and blue glazed tea bowl (kese) fragments. Two additional fragments of Celadon pottery decorated on both sides in light turquoise and matte white were discovered. A fragment of a tea bowl of a matte white color was also found made in the same style, the inner side of which was decorated with floral ornaments similar to those mentioned above. In these instances, the fabric appears grayish fine paste with no inclusions (for examples see pg 70-71, Ib_20_C_IV_212_I010).

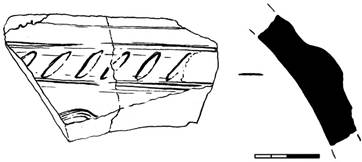

Finally, a unique spout from a water jug with alternating ridges and decorated with alternating depressions was also found (see pg. 131-fig. 158; Serial no. Ib_20_C_IV_212_I011).

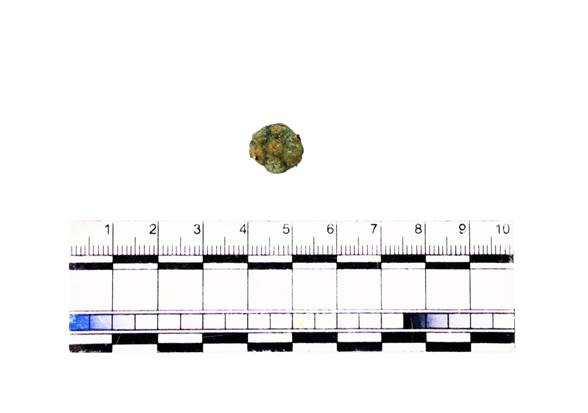

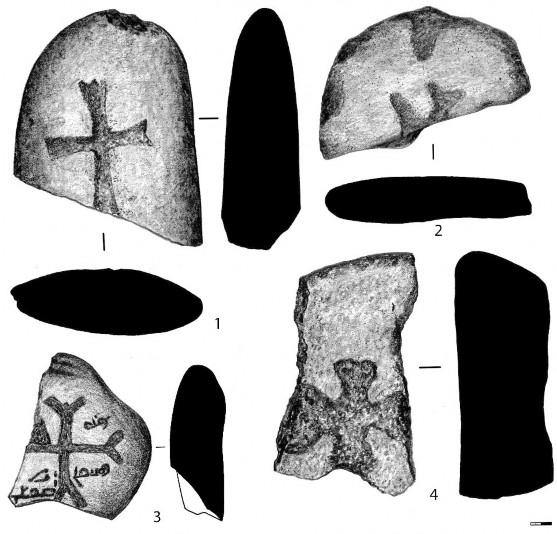

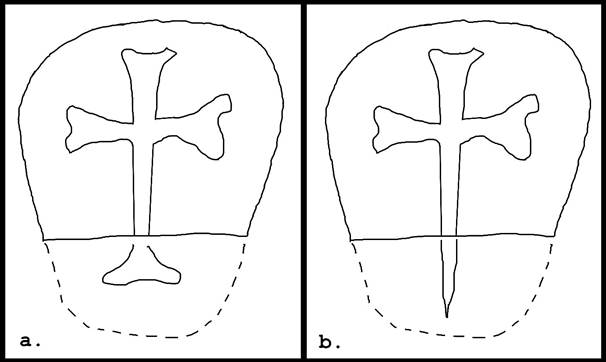

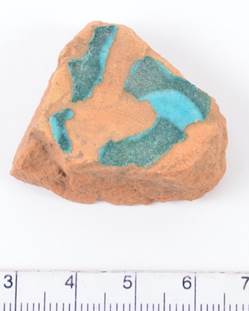

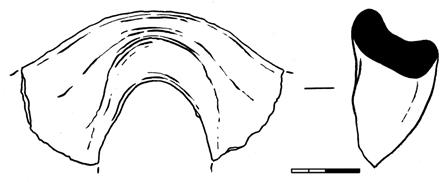

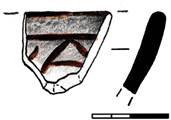

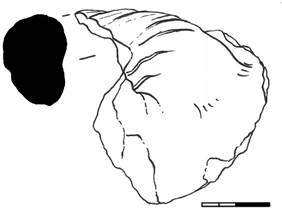

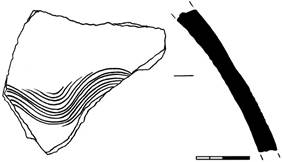

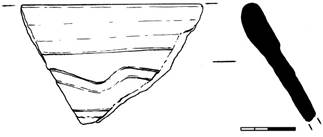

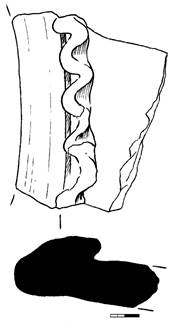

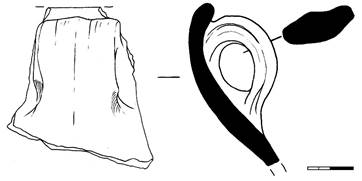

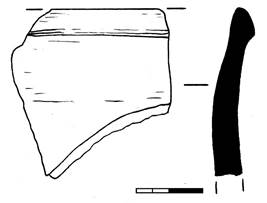

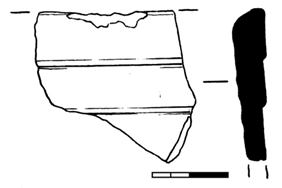

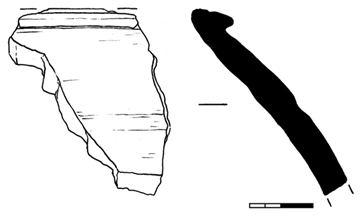

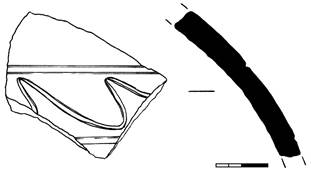

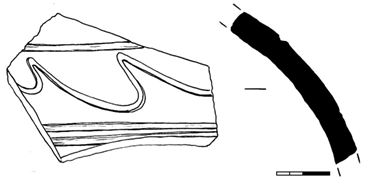

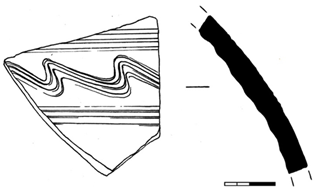

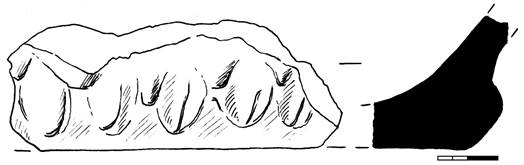

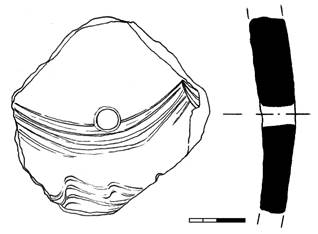

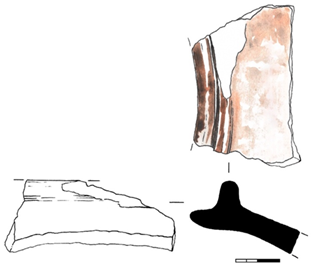

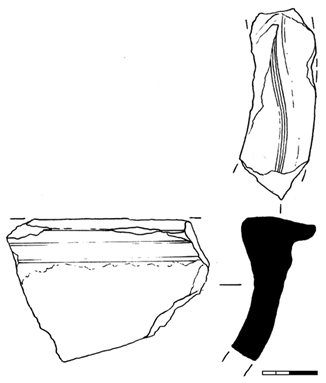

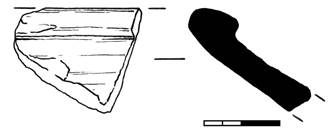

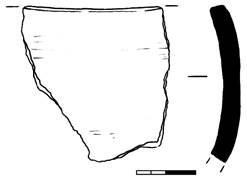

Locus 213. Kayrak (gravestone). In the central section of the U-12/L-212 during excavations at an elevation x - 410209.333; y- 4887007.524 and a level of 597.657 m asl., a flat gravestone (kayrak) of white granite was found that was damaged on all four side. On one side, a partially damaged cross inscription with flared-ends was noted. The stone’s damage was probably due to plowing and was likely originally part of a much larger stone. This is the first kayrak found at Ilibalyk made of white granite. The stone measures 22 x 10 x 7 cm. The incised cross is 9 x 9 cm with a depth of 0.3 cm. (Serial no. Ib_20_С_IV_213, see pgs 50; 132-fig.165).

Locus 214. The collapse of a tandoor (oven/furnace). During clearing of the section along the northern edge of Unit 12 at 3.70 m south of the designated boundary at mark x: 410201.844; y: 4886998.031 at a level of 597.814 m asl. scattered wall fragments of a tandoor (furnace/oven) were found. The tandoor was placed into a dense, loamy area. The inner surface of the tandoor wall was covered with a white slip. The walls of the tandoor, as well as the loamy space of the surrounding area were calcined which, as expected, indicated burning. Due to the significantly damaged walls of the tandoor, its actual dimensions could not be estimated.

Initially, this feature was puzzling due to the fact that it was approximately 20 meters south of Unit 3 which contained several graves, including one child’s grave at about the same level, suggesting that the tandoor was contemporary with the cemetery. This may indicate possible funerary meal preparation on site, or the furnace was used for heating purposes. Either, or both, functions may have been utilized since eventually walls from the structure in U-12 were discovered nearby. It is yet to be determined if this particular furnace was inside or outside the structure, as opposed to the one found inside the outer eastern wall (L-220) and will need

to be examined further at a later date. Tandoors do not appear to be precisely dated according to size or type in the archaeological record in Central Asia and can span over several centuries.

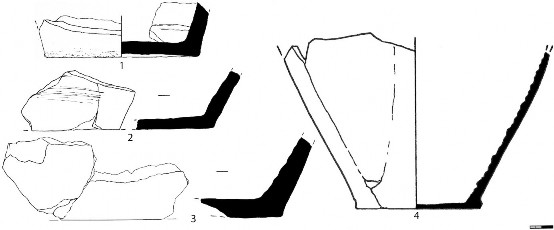

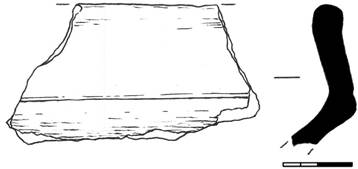

Locus 215. Fired bricks near the western boundary of the excavation site. While digging the layer of soil to a shovel-blade’s depth, near the western boundary of Unit 12 at mark x: 410188.565; y: 4887004.514 at a depth of 597.484 m. asl, two fragments of red fired bricks were found in a dense, loamy layer of soil.

The first brick measured 18 x 20 x 6 cm and lay flat in the soil. Adjoining it laying slanted on its edge was the second brick fragment which measured was 20 x ? x 6 cm. (Due to its placement in the soil, the exact measurement of this second brick could not be obtained). The surrounding surface around the bricks was tamped down and damaged by roots of a nearby tree. The feature was not excavated any further and will have to be examined at a later date. In this same sector a small piece of fluorite was found that appeared to be part of a vessel. If so, this would indicate another high-status fragment. The color of the fluorite is light green with white flecks and black impurities in the crystal.

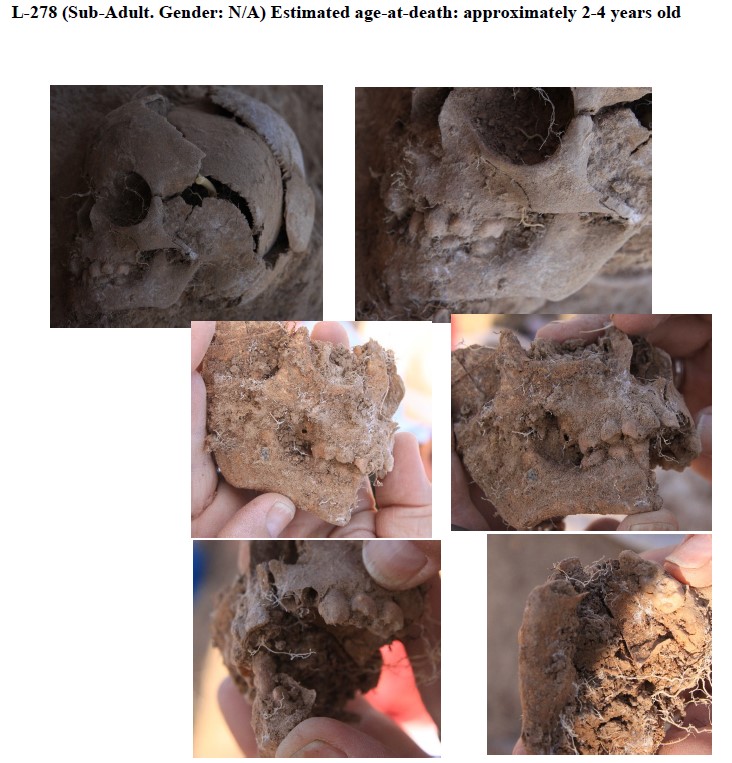

Locus 216. Child's grave. While clearing a space along the northern edge of Unit 12, approximately 3.70 m south of the boundary at mark x: 410211.640; y: 4887009.038; at a level of 597.618 m asl. scattered human infant bones were found within a 60 x 40 cm area. The skeletal remains belonged to an infant child, either a still born or just a few weeks old. The bones, like the skull, were badly damaged. Judging by the surviving remains, the child was buried at a shallow depth, with its head to the west. The sex of the child and the time of burial could not be established. (Appendix F, Field Forensic Analysis, pg. 187).

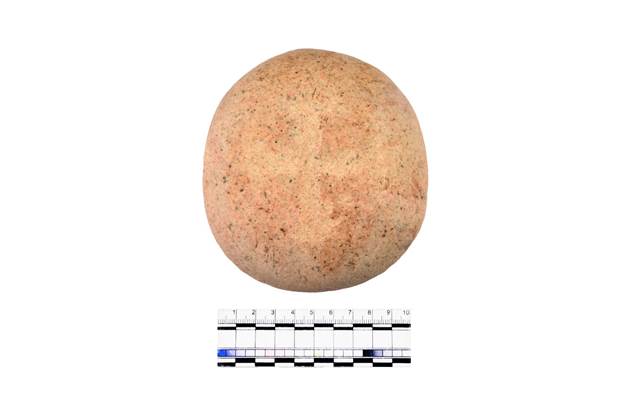

Locus 217. Boulder. Following clearing the topsoil surface and while digging the second layer of soil in the central section of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410198.877; y: 4887001.931 and at a level of Z: 597.452 m asl. a large boulder-sized stone was discovered along with what eventually was revealed as a long northern wall of the room of the exposed structure (locus 250), lined with mud bricks with an east-west orientation. In the central part of the wall’s masonry, this large stone with an irregular circular shape was mounted level with the full height of the wall. The top of the stone was flat, and its edges were rounded. The exact purpose of the stone in the masonry of the wall was not established. One possible interpretation is that it served as a base for a wooden column. The stone measured 65 x 41 x 26 cm.

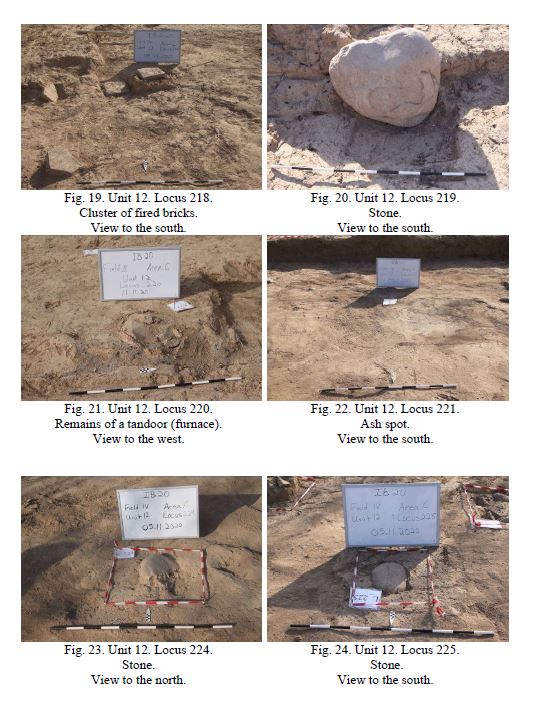

Locus 218. Cluster of 4 bricks. While clearing at a shovel's depth, near the northern edge of Unit 12 at level 597.666 m asl., a fragment of a red fired square brick was found in a dense, loamy layer. It measured 25.5 x 25.5 x 5 cm. Fourteen cm below it, at a level of 597.520 m asl. lay a similar square-shaped brick measuring 27 x 27 x 5 cm. Eventually, a total of 4 bricks were found in the vicinity. Bricks 1, 3 and 4, located at different depths and on different sides, formed a type of triangle formation. From brick 1 to brick 3 were separated by 1 m and lay to the east. From brick 3 to the pentagonal-shaped brick 4, located in the northeast, the distance extended 89 cm. From the pentagonal brick 4, the distance to brick 1 was 1.24 m. A distance of 58 cm separated brick 3 and brick 2 which was located next to brick 1, but below that latter’s level. Three of the four bricks (1,3, and 4) were at a similar level, while brick 2 was at a lower depth by 14 cm. Determining the exact purpose of the brickwork proved problematic, however, it is possible that these bricks were part of a northern entrance for the structure associated with the Room 2 which may have been a corridor (L-242). The bricks, if they were associated with a threshold archway could have collapsed randomly as discovered.

The four bricks are described as follows:

Brick 1. This fired brick had a square shape measuring 25.5 x 25.5 x 5 cm. Coordinates: x: 410203.883; y: 410204.643; at 597.666 m. asl

Brick 2. This fired brick had a square shape measuring 27 x 27 x 5 cm. Coordinates: x: 410204.249; y: 4887004.263; at a level of 597.520 m asl.

Brick 3. This fired brick had a square shape measuring 28 x 28 x 5 cm. Coordinates: x: 410204.966; y: 4887004.423; at a depth of Z 597.650 m asl.

Brick 4. This brick had a pentagonal shape measuring 26.5 x 21 x 5 cm. Coordinates: x: 410203.883; Y: 4887004.150, at a depth of 597.666 m asl.

Locus 219. Boulder. Following the clearing of the topsoil in Unit 12 and while digging the second layer of soil in the central section of the unit at UTM coordinates x: 410203.254; y: 4886998.962; at a depth of 597.434 m asl, excavators eventually discovered a long northern wall (locus 250) associated with what was designated as Room 1 (Locus 230). It was lined with mud bricks in an east-west direction. In the eastern part of the wall’s masonry, this large, oval- shaped boulder-sized stone was discovered and mounted to the full height level with the wall. The top of the stone was flat, and the edges of the stone were rounded. The exact purpose of the stone in the masonry of the wall was not established. One possible interpretation is that it served as a base for a wooden column. The stone measured 58 x 60-40 x 18 cm.

Locus 220. The collapse of a tandoor (furnace/oven). While clearing the space of the eastern section designated Room 3 (L- 240) at UTM coordinates x: 410211.081; y: 4886999.981; at a level of 597.647 m. asl, scattered tandoor (oven) walls were discovered. The tandoor was placed into a dense, loamy area. It was round in shape with partially preserved 4 cm thick ceramic walls. The inner surface of the tandoor wall was covered with a white slip and incised prior to firing with horizontal and oblique lines. The walls of the tandoor, as well as the loamy space of the locus, were calcined. The remaining part of the preserved wall in the middle section was 50 cm in diameter. Due to the significantly damaged walls of the tandoor, its actual dimensions could not be estimated. This oven was located within the eastern outer wall (L-240) demonstrating that this feature was probably providing heat to the room and perhaps the entire building.

Locus 221. Ash spot. A black ash spot located 2 m from the southern boundary of Unit 12 at coordinates x: 410204.377; y: 4886999.186 at a level of 597.646 m asl. The locus consisted of two oval spots, or areas of burning, located 20 cm adjacent to each other and just south of the southern wall (L-246). The size of the first spot was 1.20 x 0.90 m. The size of the second spot was 1.40 x 0.90 m. Time prohibited further investigation.

Locus 222. Ash spot. While clearing the soil layer in the far southwestern part of Unit 12, an ash spot was found 1.80 m from L-223. The black ash spot had an amorphous shape and measured 38 x 62 cm in size. It was located 80 cm from the southern edge of Unit 12 at coordinates of x: 410189.007; y: 4886991.055 at a depth of 597.155 m. asl and just south of the southern wall section (L-246). The stain consisted of ash and soot, with the inclusion of loamy soil. The thickness of the spot was at least to a depth of 10 cmbs. Within the borders of the spot, grass and nearby tree roots were detected. A significant amount of pottery and animal

bones were found in this section, thus there is a possibility that this is a midden. Time prohibited further investigation.

Locus 223. Ash spot. While clearing the soil layer in the southwestern part of the excavation site, an ash spot was found 1.80 m from L-222. The black ash spot was of an amorphous shape and measured 38 x 62 cm in size and was located 70 cm from the southern edge of the excavation at coordinates x: 410191.982; y: 4886991.170 at a depth of 597.193 m asl. The stain consisted of ash and soot, with the inclusion of loamy soil. The thickness of the spot was at least to a depth of 10 cmbs. Within the borders of the spot, grass and nearby tree roots were detected. A significant amount of pottery and animal bones were found in this section, thus there is a possibility that this is a midden. Time prohibited further investigation.

Locus 224. Boulder. While clearing the soil around Locus-230 (Room 1) a large whitish- gray boulder which rested on the ledge of the southern wall (L-253) near the possible southern entrance to the structure of Unit 12 was discovered. It lay at a level of 597.404 m asl. and lay

4.8 meters to the west of the stone identified at Locus 219 and 1.8 meters to the east the smaller stone at L-225. No masonry or mudbricks were detected around the stone. The stone measured 32 x 23 cm length and width, but it was not removed from the soil, thus its height is unknown.

Locus 225. Boulder. While clearing the topsoil and digging the second layer of soil in the central part of Unit 12 (L-230) at UTM coordinates x: 410202.643; y: 4887011.787 at a level of 597.049 m asl., excavators found this stone along the southern wall (Locus 253) at the edge of Room 1 (Locus 230). It was lined with mud bricks in an east-west direction. In the central part of the masonry of the wall, this large, oval-shaped stone was mounted to the full height even with the wall. The top of the stone was flattened, and the edges of the stone were rounded. The exact purpose of the stone in the masonry of the wall was not established. One possible interpretation is that it served as a base for a wooden column. It could also have been associated with a door threshold if, indeed, the possible southern entrance is to the east of this stone. It measured 30 x 25 x 8 cm.

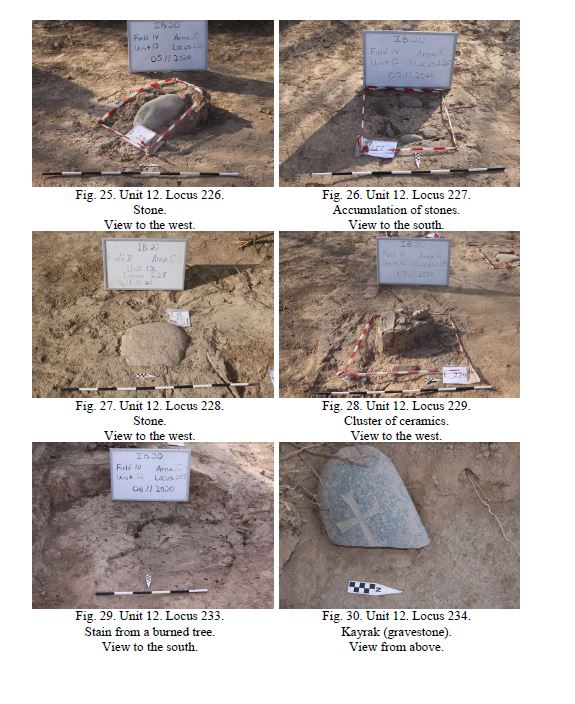

Locus 226. Boulder. While clearing the topsoil and digging the second layer of soil in the western part of Unit 12, excavators found this boulder-sized stone along the long southern wall segment (Locus 253) at the edge of Room 1 (Locus 230). It was lined with mud bricks in an east-west direction. This stone was located at the western end of the wall’s masonry, on the floor of the room. It was a large oval-shaped rock at UTM coordinates x: 410193.456; y: 4886997.041 at a level of 597.431 m asl. The top of the stone was flattened, and the edges of the stone were rounded. The exact purpose of the stone in the masonry of the wall was not established. One possible interpretation is that it served as a base for a wooden column. It measured 40 x 13 x 10 cm.

Locus 227. Accumulation of stones. While clearing the topsoil and digging the second layer of soil in the southern part of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410195.423; y: 4886996.515; at a level of 597.362 m. asl. and located 90 cm south of the southern wall (Locus 247) of the Room 1 and lined with adobe bricks in an east-west direction. This locus designated a 70 x 70 cm cluster of 3 stones of various sizes and shapes. The purpose the stones’ placement near the wall has not been established. It may be indicative of rubble from collapse.

Locus 228. Boulder. While clearing the topsoil and digging the second layer of soil in the western part of Unit 12, excavators discovered this stone along the southern wall (Locus 253) of Room 1 (Locus 230). It was lined with mud bricks in an east-west direction. This large

oval-shaped boulder was mounted to the full height level with the wall at UTM coordinates of x: 410192.589; y: 4886995.739 at a level of 597.287 m. asl. The top of the stone was flat, and the edges of the stone were rounded. The exact purpose of the stone in the masonry of the wall was not established. One possible interpretation is that it served as a base for a wooden column. It measured 40 x 39 x 10 cm.

Locus 229. A cluster of ceramics and debris. While clearing the area outside the boundaries of the structure (locus 230) on the southwest side at UTM coordinates x: 410196.247; y: 4886995.223; at a level of 597.424 m. asl. an accumulation of pottery fragments and fired brick fragments was found. Within this cluster of fragments, the rim and sidewall of a jug were found. The rim was decorated with alternating fingertip impressions along the edge. Sidewalls and rims from water-bearing vessels were also found within the cluster. The area of debris measured 50 x 60 cm.

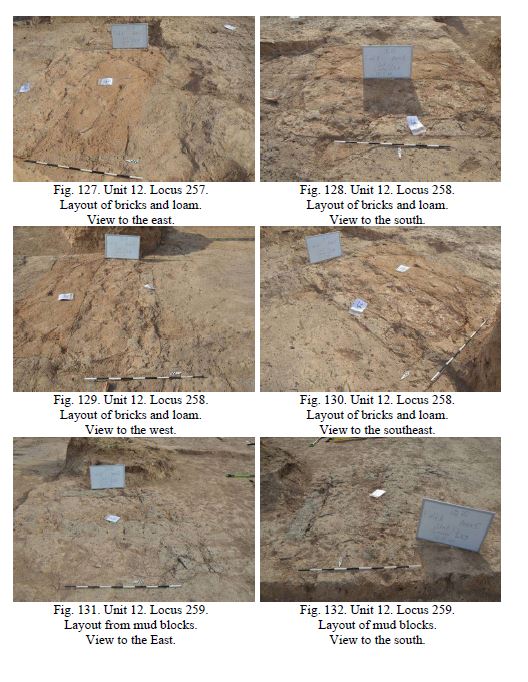

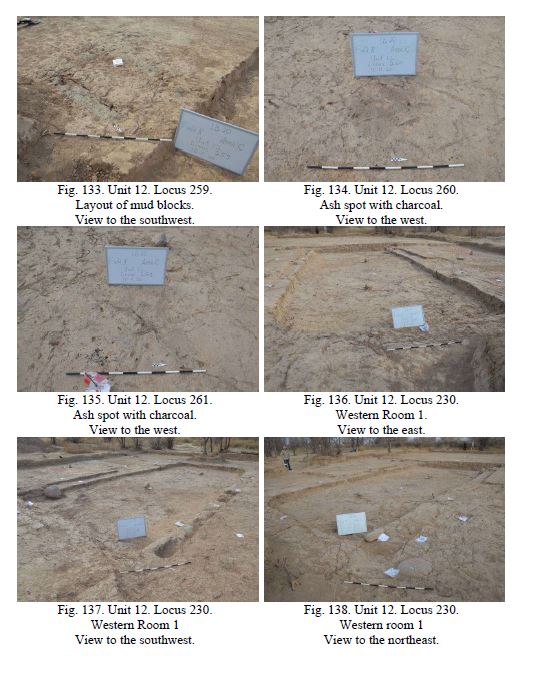

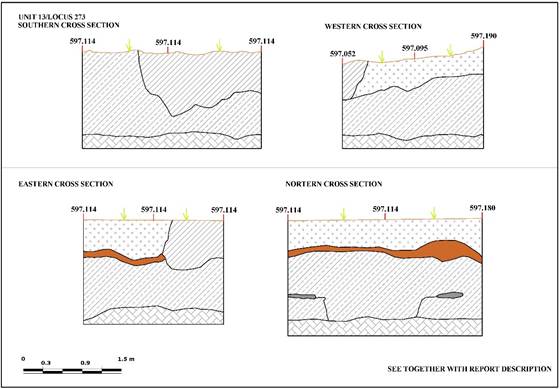

Locus 230. Level for Room 1. While clearing a layer in the central section of Unit 12 at the surface UTM coordinates x: 410199.163; y: 4887002.264; at a level 597.462 m asl., the contours of the northern (locus 250) and southern (locus 253) walls of the room (designated Room 1) emerged. These walls were laid parallel to each other. During further clearing of the space on the west and east sides, excavators also revealed brick walls laid out parallel to each other, separated by the excavated space of the described room.

The room had a rectangular layout which measured 11 x 4.90 m. The northern wall of the room (designated locus 250) was identified and made from adobe bricks along an east-west axis. In the southern part of the room two sections of wall were also found (locus 246 and 247), also made of adobe bricks along an east-west axis. Ledges were identified along the northern and southern walls of the room adjoining the masonry. Within the masonry of the northern and southern ledges, boulders and stones of various sizes were embedded whose purpose and functionality are unknown, but one possibility is that they served as bases for wooden support columns. A wall was found on the western side of the room (identified as locus 248) which extended in a north-south direction. Both the northern (locus 250) and southern (locus 247) walls appeared to form rounded corners of the room on the western side of Room 1. On the eastern side of the room, there was a brick partition wall (locus 244) with a north-south orientation. The terminal end of the northern wall (locus 250) appeared to form a corner to the room. On the south side, the inner wall (locus 246) and the outer wall (locus 252) created a partition for the eastern section of the room. Along the southern and northern walls of the room there were ledges made of adobe bricks. On the north side, behind the wall (locus 251), there was a rectangular niche (locus 251). On the southern part of Room 1, behind the wall (locus 253) of the room, there was a partially excavated wall (locus 247), built of mud bricks with a north-south orientation.

While clearing the loose layer of loam within Room 1 (locus 230) charcoal and plant roots were detected within the room. Cultural material, such as fragments of wheel-thrown ceramics were found in the soil fill of the room. These included the lower half of a water jug; fragments of a glazed oil lamp with a loop-shaped, vertical handle that included a thumb rest containing a decorative feature with a possible cruciform design; sidewalls and a fragment of a handle from a water jug, as well as a rim and fragments belonging to another jug-type vessel.

While clearing the surface of Room 1 at UTM coordinates x: 410201.164; y: 4887001.324 at a level of Z 597.098 m asl. excavators found a tamped earthen floor. An ash spot (locus 261) and a calcination spot (locus 236) were discovered on the floor of the room

along with an accumulation of ceramic fragments (locus 237). Charcoal was detected in the excavation layer on the floor of the room along with animal bones within the room. Neither metal, nor glass items were found in the room. One pottery vessel located in the western half of Room 1 contained at least half of its remaining fragments, making reconstruction of the vessel possible (See pg. 132-fig 167).

Locus 231. Boulder. While clearing the topsoil and digging the second layer of soil in the central section of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410203.254; y: 4886998.962 at a level of 596.963 m. asl. excavators discovered a large, oblong-shaped boulder in association with the long northern wall of Room 1 (locus 250). The wall was lined with mud bricks in an east-west orientation. This boulder was located in the eastern section of the masonry of the wall. This large oval-shaped stone was mounted to the full height of the ledge upon which it lay. The top of the stone was flat, and the edges of the stone were rounded. The exact purpose of the stone in the masonry of the wall was not established. One possible interpretation is that it served as a base for a wooden column. It measured 34 x 47 cm. Most of the stone was embedded into the masonry of the wall, so the exact height of the stone is not clear since it was not extracted.

Locus 232. Boulder. While clearing the topsoil and digging the second layer of soil in the central part Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410203.254; y: 4886998.962; and at a level of

597.292 m. asl., this stone was discovered by excavators along the long northern wall (locus 250) of Room 1 lined with mud bricks in an east-west orientation. This large amorphous stone was in the western part of the masonry of the wall and was mounted on the full height of the ledge. The top of the stone was flat, and the edges of the stone were uneven. The exact purpose of the stone in the masonry of the wall was not established. One possible interpretation is that it served as a base for a wooden column. It measured 62 x 47 x 25 cm.

Locus 233. Burnt root from a tree. While clearing in the space of the area of the partition wall (locus 244) from the eastern side of Room 1 (locus 230), traces of burning, charcoal, and ash were found at UTM coordinates x: 410195.474; y: 4887001.735; beginning at a level of

597.351 m asl reaching a level of 596.963 m. asl. just below the probable dirt floor level. Later, while clearing a layer of ash near the wall, excavators found the burnt remains of a root system that was from a trunk of a tree. The diameter of the spot was 32 cm. The tree trunk had almost burned away completely. A terminal root fragment remained on the loamy floor. This may provide an explanation for the significant amount of burning within Room 1 discovered, yet this is indeterminate. If this was a major source of burning, then it would suggest a significant time lapse between the detected burning within the structure based on the time it took for the tree to grow within the structure and subsequently be burned down. A radiocarbon sample taken of burned wood found within Room 1 to the northwest of this locus could potentially shed light as to whether the burning found from this tree was responsible for the calcine deposits within Room 1 or if they were due to destruction of the structure by fire leading to possible collapse.

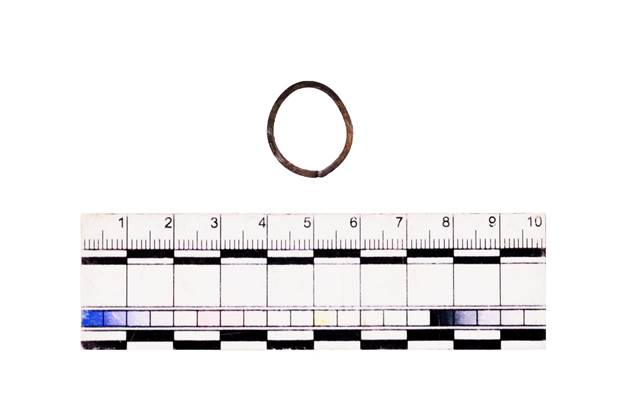

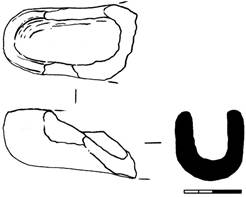

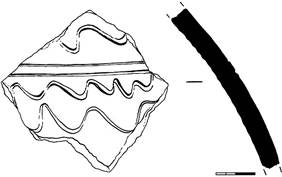

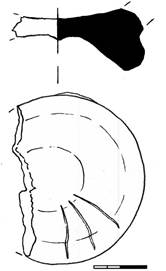

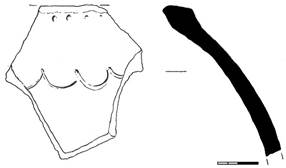

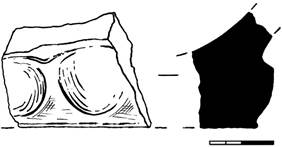

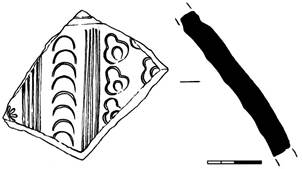

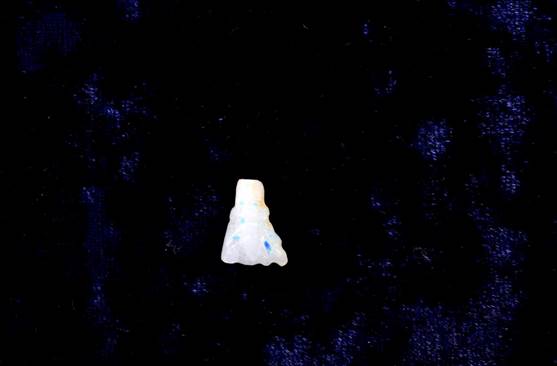

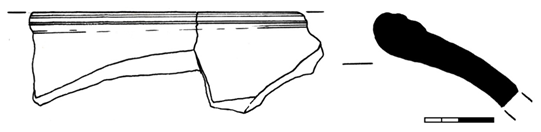

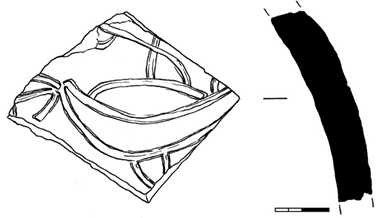

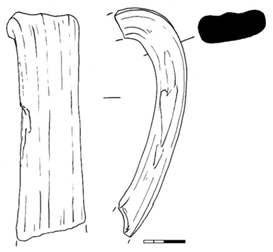

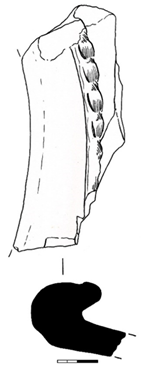

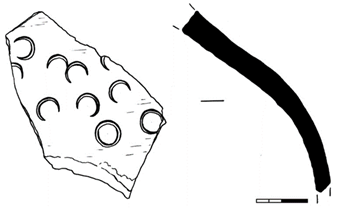

Locus 234. Kayrak (gravestone). While clearing the topsoil and digging the second layer of soil in the far northern border of Unit 12 and Unit 9C while clearing Locus 185 a fragment of an oval, gray river stone with a rounded surface and a rounded oval edge was found in a layer of loose loamy soil under a system of tree roots. It was found at UTM coordinates x: 410200.989; y: 4887010.666; at a level of 597.703 m. asl at a depth of 40 cm below the surface. Upon careful examination of the rounded surface of the stone an inscribed cross with flared ends was detected. Thus, the stone was identified as a kayrak (gravestone).

The kayrak lay in flat, loamy soil. The upper edge has an arched shape with traces of chipping damage likely due to plowing. The surface of the stone was oval in the profile. On one of the sides, a cross was inscribed using the method of continuous chisel points and further partial grinding of the embossed image. The size of the cross is 12 x 9 cm. The four crossbars connected in the center and the ends of which are slightly bifurcated. Like the stone, the lower part of the cross is partially chipped off and damaged. The size of the kayrak is 23 x 18.5 x 7 cm. This find reintroduced the idea this section of locus 185 might actually be a grave, yet, so far this has not been determined (see locus 185 description above).

Locus 235. Fragment of burnt wood. While clearing the space around locus 185, on the northern border outside Unit 12 and Unit 9C on the dense, gray loamy soil a charred piece of wood was found at UTM coordinates x: 410202.146; y: 4887011.352 at a level of 597.025 m. asl. This piece of wood was found while clearing down to the current revealed surface of the previous season. This seems to indicate that the area was subject to burning and that this level was exposed at the time, either as part of an open courtyard, or an enclosed structure. This could also indicate that certain graves excavated at previous seasons were interred close to the original occupational surface. It was indeterminate if this piece of wood was worked, or possibly part of the structure from U-12 or part of a possible separate structure that encompassed the area of L-185. It is consistent and on the same level as much of the charcoal fragments found throughout the gray colored soil that was eventually exposed across the expanded section of L-185.

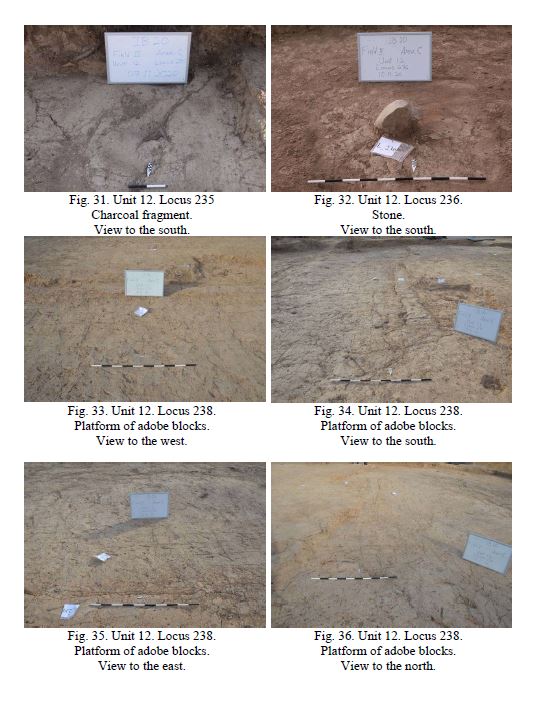

Locus 236. Boulder. While clearing the soil tamped floor in the eastern part of Room 1 (locus 230) a single stone in an inclined position was found with accompanying ash and a calcination spot at UTM coordinates x: 410197.101; y: 4886998.920; at a level of 597.050 m asl. The stone is a flattened oval shape with traces of chipping along the edges. The size of the stone is 15.7 x 19 x 8 cm. This stone appears to have rested or collapsed onto the original tamped floor surface.

Locus 237. Cluster of ceramics. While clearing the earthen tamped floor in the central part of Room 1 (Locus 230), a cluster of pottery fragments was recorded and excavated within ash and an incineration spot at UTM coordinates x: 410197.101; y: 4886998.920 at a level of

597.050 m. asl. These fragments of ceramic vessels were located compactly in an area of 70 x 90 cm. The potsherds included fragments from ornamented water jugs of wheel-thrown red- clay and gray-clay vessels; as well as fragments of the wall and rim of a deep bowl These latter fragments contained enough sherds that made partial reconstruction of the vessel possible. (See pg. 132, fig. 167)

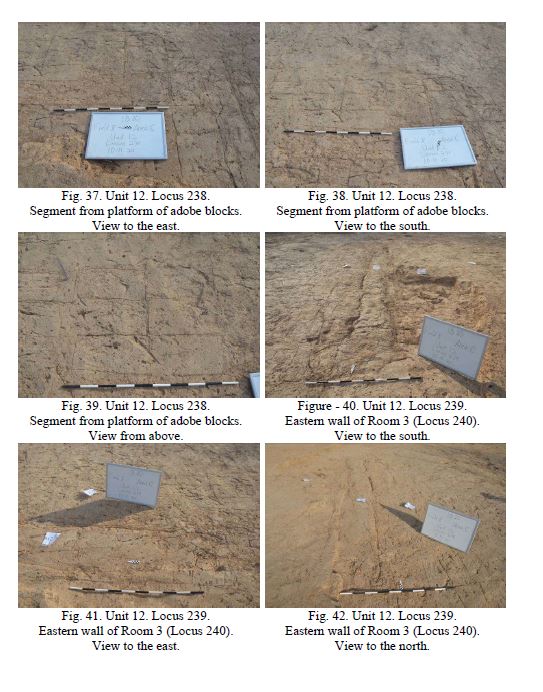

Locus 238. A platform of adobe blocks. While clearing loose loam in the eastern part of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410212.526; y: 4886999.576; at a level of 597.537 m. asl, excavators found on the surface mud blocks of various sizes which were bonded with clay mortar. The blocks appeared laid out on the floor of the Room 3 (locus 240) with a north-south orientation. The size of the cleared area was 5.30 x 2.50 m, which is an area of 13.25 m2. The size of the blocks was not uniform and varied from 40 x 20 cm to 56 x 28 cm. In the cleared area during excavations, fragments of ceramic vessels were found which included water jugs, decorated wheel-thrown red clay and gray clay vessels, as well as fragments of sidewalls and the rim of a storage vessel. Along the border of this site, fragments of sheep and cattle bones were also found.

Locus 239. Eastern wall of Room 3 (locus 240). While clearing a layer in the eastern part of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410193.848; y: 4887008.239; at a level of 597.585 m asl. the contours of a wall of what was designated Room 3 was found. It was lined with mud bricks along a north-south axis and was made of mud bricks of a standard size 40 x 20 x 5 cm. They were joined together with clay mortar. On the west side of the room, at the base of the masonry of the wall, a tandoor (oven/furnace) (locus 220) was found. On the east side, a location lined with mud blocks (locus 238) was discovered that was laid out in a north-south orientation. To the north, the masonry of the wall seems to cut off near the designated site (locus 238). There was a wall on the south side which adjoined the corner to a similar location.

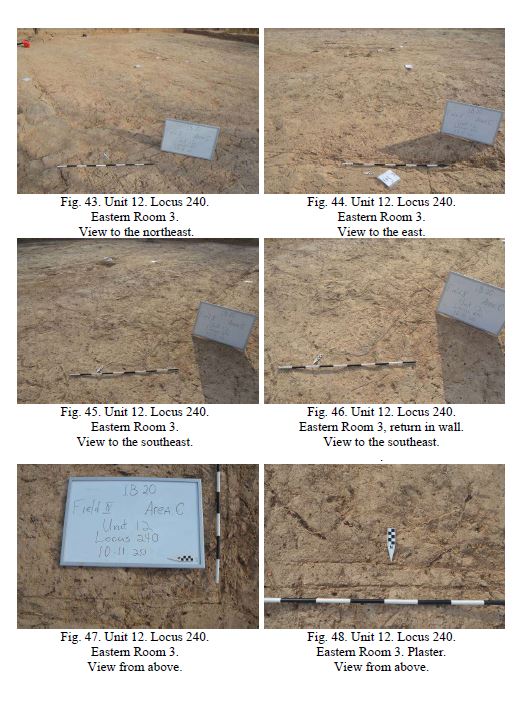

Locus 240. Room 3. While clearing a layer in the eastern part of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410211.574; y: 4886999.794; at a level of 597.694 m. asl, the contours of the eastern wall (locus 239) and western wall (locus 241) of Room 3 emerged. They were laid out parallel to each other in a north-south orientation. During further clearing in this area on the western and eastern sides, excavators revealed the brick walls laid out parallel to each other and separated by the excavated space of the described room. The room had a rectangular layout, measuring 6.40 x 4.50 m, with an area of 28.8 m2.

On the west side of Room 3, a wall (locus 241) was found laid out with a north-south orientation. On the south side, this wall adjoins to a another wall with its terminal end (locus 245). On the east side of the room a brick wall (locus 239) with a north-south orientation was also delineated. Along the eastern wall (locus 239) near the masonry of the wall, a tandoor (oven/furnace) was also discovered (locus 220). While clearing of the loose layer of loam within the room, excavators detected charcoal and plant roots inside the room. Fragments of wheel-thrown ceramics were found within the fill of the room including the lower portions of water-bearing jugs, as well as the sidewall and fragment of a handle from a water-bearing jug.

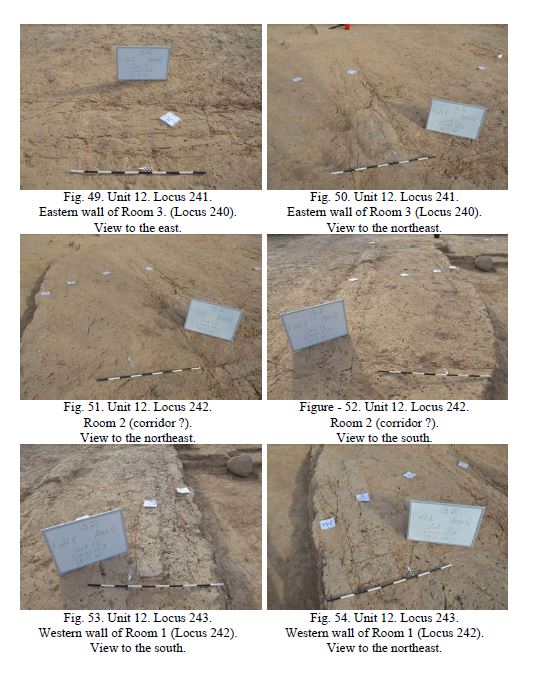

Locus 241. Eastern wall of Room 3 (Locus 240). While clearing a layer in the eastern part of Unit 12 at the surface level to the east of the excavated Room 1 (locus 230), the contours of a wall of a room made of pakhsa (tamped earth) appeared which was oriented along a north- south axis. It was found at UTM coordinates x: 410201.359; y: 4886996.362; at a level of 597.685 m. asl. Its masonry was made of a dense, light brown soil. The size of the wall was

6.10 x 0.60 m. To the east, parallel to this described wall, there was an eastern wall made of mud bricks (locus 239) near which a tandoor (oven/furnace) was located (locus 220). On the west side of locus 241 a narrow, rectangular area, presumably a corridor space (locus 242) extended in a north-south orientation. The masonry of the wall cut off at the northern side of the designated locus (locus 238). On the south side, the wall adjoined the other wall at its terminal end to the wall segment labeled locus 245.

Locus 242. Room 2 (corridor?). While clearing a layer in the eastern part of Unit 12 behind excavated Room 1 (locus 230). the outlines of tamped earth and grooved walls of the room emerged. It was laid out parallel with the wall designated L-241 with a north-south orientation. The surface level UTM coordinates were x: 410206.196; y: 4886999.927 at a level of 597.707 m. asl. Further clearing of the space on the western and eastern sides, revealed brick walls laid out parallel to each other and separated by the excavated space of the described room. The room (corridor?) had a rectangular layout measuring 4.80 x 1 m, with an area of 4.8 m2. On the western side of the room a brick wall (locus 243) was constructed of adobe bricks along a north-south axis. To the south of the building, a segment of the outer southern wall (locus 245) is visible, also made of mud brick. To the east of the room was a wall (locus 241), oriented in a north-south direction. On the south side, the currently described wall adjoined its terminal

end with the southern wall segment (locus 245). The currently exposed floor of the room was a loamy, dense, light-brown soil. While clearing this loam, charcoal and plant roots were detected inside on the floor of the room. In addition, significant glazed pottery finds were found within this section, including a finely decorated blue glazed pottery fragment with painted decoration and almost all the fragments of a green-glazed lamp (serial no. Ib_20_C_IV_212_I016, pgs. 58-fig. 5.10; 132-fig. 167).

Locus 243. Western wall of Room 2 (locus 242, corridor?). While clearing the layer in the eastern part Unit 12 (near locus 230) at UTM coordinates x: 410205.542; y: 4887000.289; at a level of 597.688 m. asl., the contours of the wall of Room 2 appeared. It was constructed of adobe bricks along a north-south axis. The mud bricks had a standard size 40 x 20 x 5 cm and were fastened together with clay mortar. To the east side was a pakhsa (tamped earth) wall (locus 241) which also had a north-south orientation. To the south, the wall (L-243) adjoined the brick wall segment (locus 245) at its terminal end. The larger, rectangular Room 1 (locus 230) was located to the west of the wall which is separated by the partition wall (locus 244). The wall measured 3.50 x 0.80 m.

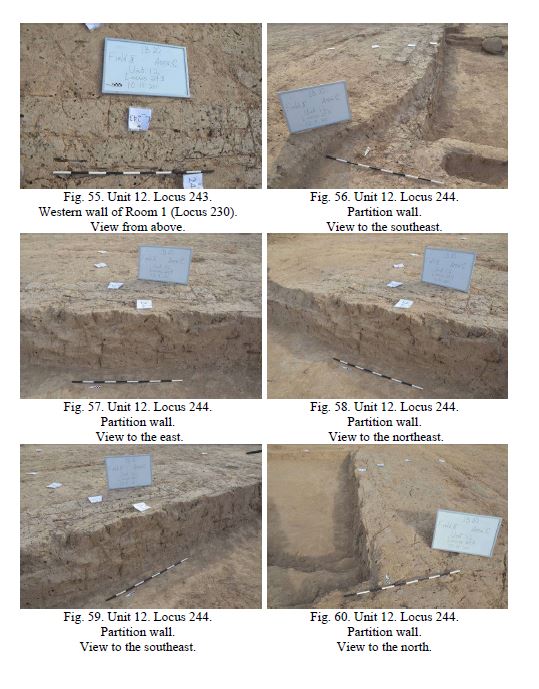

Locus 244. Partition wall. While clearing the layer in the eastern part of Room 1 (locus 230) at UTM coordinates x: 410205.786; y: 4886995.975 at a level of 597.646 m. asl. the contours of a wall on the east side of the room were revealed. It was constructed of adobe bricks in two courses along an east-west orientation. The masonry was dense and made of a light brown soil. The wall measured 5.40 x 0.40 m. To the east, perpendicular to the described wall, was an eastern wall made of mud bricks (locus 243), behind which is located a Room 2 (corridor?) (locus 242). On the western side is the area of rectangular Room 1 (locus 230) extending in an east-west orientation. To the north, the masonry of the wall connected to the wall identified as locus 250, behind which is a possible niche (?) (locus 251) which formed the northeastern corner of the room. The terminal end of the wall to the south adjoined to the brick wall (locus 246) and to the southern ledge of the side of the wall which adjoined to the end of the southern wall segment (locus 245). The lower elevation of the wall is 597.085 m asl., which is the floor elevation level for locus 230, the height of the remaining wall is 57 cm from the floor surface.

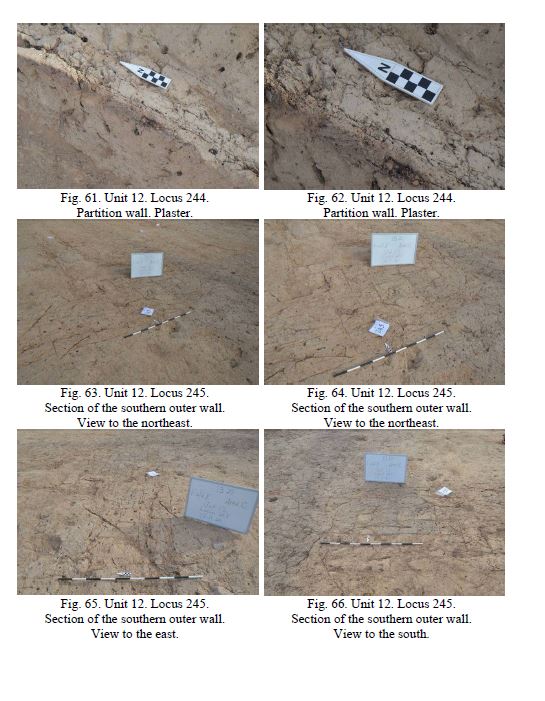

Locus 245. Section of the southern outer wall. While clearing a layer of loose loam on the eastern side of Unit 12, outside the identified Room 1 (locus 230) at UTM coordinates x: 410209.474; y: 4886999.858; at a level of 597.656 m. asl, the contours of a brick wall of the room(s)located to the east of Room 1 (locus 230) behind the dividing wall (locus 244). This described section of the wall was lined with mud bricks along an east-west axis. The preserved masonry of the wall is 1.5 bricks wide. The mud bricks were of standard size 40 x 20 x 5 cm and fastened together with clay mortar.

On the north, the masonry of the dividing wall adjoined the wall identified as locus 244. At this point, from the eastern edge of the wall masonry, the terminal end adjoined the turn in the wall (locus 241), which formed the southeast corner of the room (corridor?; locus 242). This wall segment measured 4.80 x 0.90 m.

Locus 246. Southwest section of the southern wall of Room 1 (Locus 230). While clearing a layer of loose loam in the central part of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410204.800; y: 4886999.600; at a level of 597.401 m. asl. the outlines of the [southern] wall of Room 1 appeared. It was constructed of adobe bricks along an east-west axis. The preserved masonry

of the wall was 3 bricks wide. The mud bricks were of standard size 40 x 20 x 5, cm and fastened together with clay mortar.

To the north along this wall was a ledge (locus 252) which extended the length of the southern wall. To the east, a dividing wall (locus 244) adjoined the wall with its terminal end and formed a corner of the room. At this point, the terminal end of the wall joined the masonry of the wall segment (locus 245). On the western side, the masonry of the wall was interrupted and formed a space that could be interpreted as an entrance, after which the southern section of the outer wall of the room began. At the southwestern end of the wall, a stone was embedded in the masonry (locus 228) which lay on the surface of the ledge. Next to the wall was another boulder (locus 219). This wall segment measured 7.30 x 0.70 m.

Locus 247. Southeast section of the outer wall of Room 1 (locus 230). While clearing a layer of loose loam 6 m from the southwestern wall of the structure in Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410197.373; y: 4886993.034; at a level of 597.270 m. asl., the contours of this wall section of Room 1 were revealed. It was constructed of mud bricks and oriented along a north-south axis. The preserved masonry of the wall was 1 brick wide. The mud bricks measured of a standard size 40 x 20 x 5 cm and were fastened together with clay mortar.

To the west of the described wall, the western outer wall (locus 248) adjoined the terminal end and formed a rounded corner in the southwest side of the room. On the east side, the masonry of the wall was interrupted and formed a gap that could possibly be interpreted as a southern entrance, after which the northern section of the outer wall of the room began. At the southwestern end of the wall, a stone was embedded in the masonry (locus 228) and lay on the surface. There was a boulder stone near the wall (locus 226). The wall measured 5.30 x 0.80 m.

Locus 248. Western outer wall of Room 1 (Locus 230). While clearing a layer of loose loam of Unit 12 at x: 410193.271; y: 4886995.816; at a level of 597.302 m. asl. the contours of a wall of Room 1 constructed of mud bricks were found that was oriented along a north- south axis. The preserved masonry of the wall was 1 brick wide. The mud bricks were of standard size 40 x 20 x 5 cm and fastened together with clay mortar.

To the north, the wall, adjoined the terminal end of the wall (locus 250) and formed a rounded corner on the northwest side of the room. On the south side, the wall, adjoining the end of the wall (locus 247), forming a rounded corner to the room. The size of the wall is 4.30 x 0.80 m.

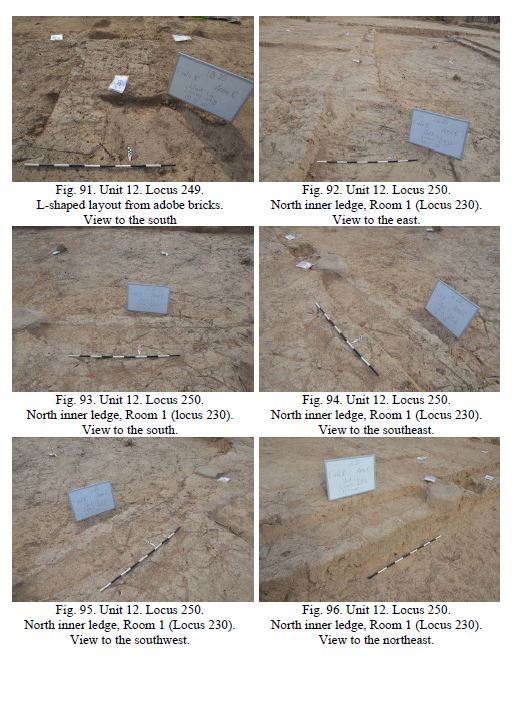

Locus 249. L-shaped layout of adobe bricks. This L-shaped layout of adobe bricks was located on the north side of the northern ledge (locus 250) of Room 1 (locus 230) at UTM coordinates x: 410202.275; y: 4887003.025; at a level of 597.494 m. asl.

The masonry was a section of the remains of the northern wall of the building and measured 1.8 meters wide. To the east of this masonry was the inner room of a possible niche (?) (locus 251). On the north side of this feature was a hardened area of tamped earth (locus 255). The masonry was constructed of mud bricks of a standard size 40 x 20 x 5 cm and fastened together with clay mortar. The edges of the masonry bear traces of coating or plaster whose thickness was 3 to 4 cm. The extended section of the masonry, located on the east side, measured north to south 1.42 cm. The western, shortened side of the masonry measured 84 cm south to north. To the west, the wall (locus 248) was oriented north-south and formed a rounded

corner to the northeast side of the room. A wall (locus 244) lay on the east side in a north-south orientation.

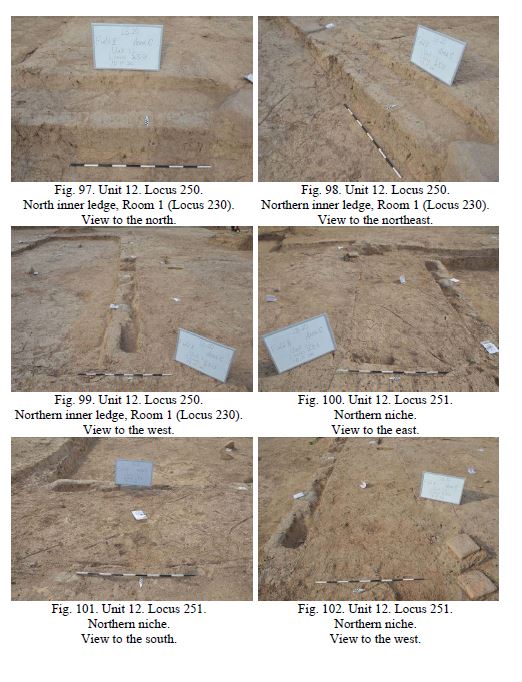

Locus 250. Northern inner ledge of Room 1 (Locus 230). While clearing a layer in the central part of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410193.848; y: 4887006.017; at a level of

597.355 m. asl. the outlines of the northern inner ledge (locus 250) of Room 1 were revealed. It was constructed of adobe bricks along an east-west axis. The mud bricks were of standard size 40 x 20 x 5 cm and were fastened together with clay mortar. Within the masonry, in approximately 3.5 meter intervals, 3 large boulder-sized flat stones of varying sizes were installed whose purpose and functionality are unknown, although one possible interpretation is that they served as foundations for wooden columns. To the west, lay a wall (locus 248), oriented in a north-south direction which forming a rounded northwest corner of the room. On the east side a brick wall (locus 244), was oriented in a north-south direction. Adjoined to the terminal end to the wall on the north, this wall formed the northeast corner of the room. On the south side the other inner ledge on the southern side of Room 1 adjoined the terminal side of wall (locus 252) and possible walkway (locus 253) and enclosed the eastern area of the room. The height of the ledge relative to the floor of Room 1 (locus 230) was 27 cm.

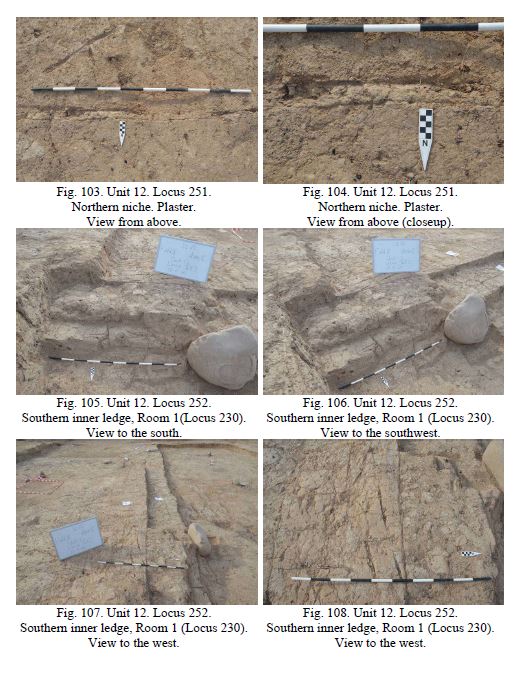

Locus 251. Northern niche. While clearing the layer in the central part of Unit 12, the contour of a possible northern niche emerged. Behind the northern wall (locus 250) of the structure a rectangular niche was found at UTM coordinates x: 410200.298; y: 4887006.017; at a level of 597.477 m. asl. The walls were made of adobe bricks. Further clearing of the space from the north, west, and east sides revealed a masonry feature of light brown loose loam that was rectangular in shape and located to the east of the L-shaped masonry (locus 249) and south of the hardened surface (locus 255). Outside the northeastern part of the niche, 4 fired square bricks were discovered (locus 218).

The niche had a rectangular layout measuring 4.30 x 1.50 m. The inner walls of the niche on the western, northern and eastern sides were covered with a layer of plaster from 3 to 5 cm thick. A layer of plaster along with a light brown loamy soil was visible after cleaning.

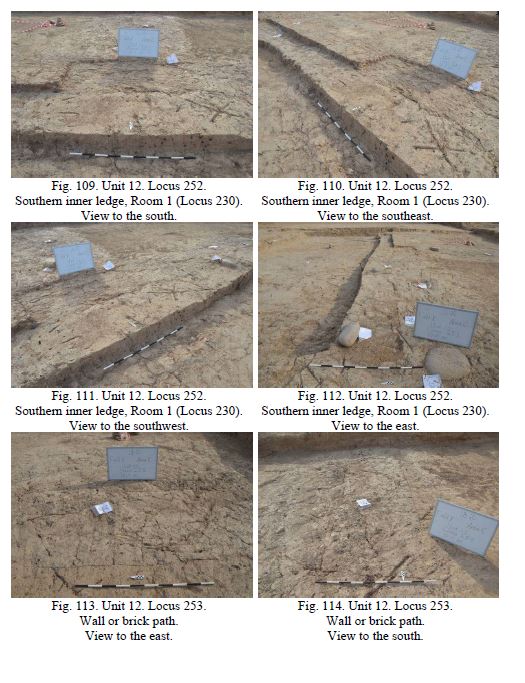

Locus 252. Southern inner ledge of Room 1 (Locus 230). While clearing the surface of Room 1 (locus 230) from the south side at UTM coordinates x: 10201.164; y: 4887001.324; at a level of 597.270 m. asl. excavators found an inner ledge made of mud bricks near the southern outer wall. The measurements of the inner ledge of the southern wall were 7.30 x 0.70 m. The height of the ledge in relation to the floor of Room 1 (locus 230) was 40 cm.

This protrusion was located just north along the south wall of the structure. The ledge was lined with mud bricks which measured to a standard size of 40 x 20 x 5 cm with an east- west orientation. A boulder-sized stone was located on the southeast ledge (locus 219). The wall partition (locus 244) was abutting the ledge from the northeast. On the west side, the masonry of the ledge terminates, forming a possible southern entrance into Room 1.

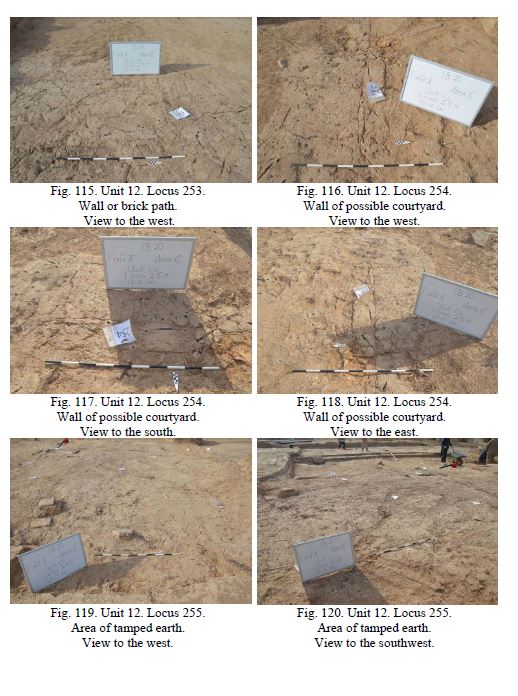

Locus 253. Wall or brick walking path. While clearing a layer in the southern part of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410201.595; y: 4886992.945; at a level of 597.320 m. asl. the contours of a wall lined with mud bricks three courses wide was found. It was oriented along a north-south axis. The masonry was made of a dense, light brown soil. The wall measured

2.40 x 1 m. The wall lay to the south of the structure and was oriented almost perpendicular to Room 1 (locus 230). We interpret this as a possible passageway or brick walking path to the southern entrance to the Room 1 (locus 230). It is unlikely to be a wall since it is not completely

parallel and is on a slightly different orientation. However, further examination at a later date will be necessary to verify this interpretation.

Locus 254. Wall of a courtyard. While clearing the site in the northern section of Unit 12 (locus 255) at UTM coordinates x: 410201.595; y: 4886992.945; at a level of 597.556 m. asl. the contours of a wall lined with mud bricks emerged. It was one course wide and oriented along an east-west axis and then made a turn to the south at the eastern side. The masonry was only partially preserved and damaged by plant roots. On the wall, a plaster coating, 2 to 4 cm thick, was also partially preserved. The wall appeared to separate the area (locus 255), from the gray, loamy area to the north (locus 185). The wall measured 2.40 x 1 m. The presence of plaster seems to raise the question as to whether this wall was on the interior of a roofed structure.

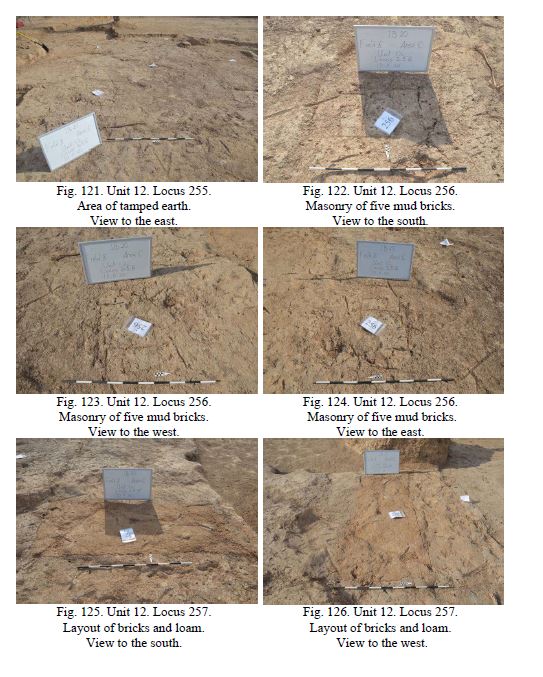

Locus 255. Hardened area. An area of hardened, compacted soil and possible mud brick measuring 7.90 x 3.10 m with a surface area of 24.5 m2 was located in the northern section of Unit 12 at UTM coordinates x: 410203.746; y: 4887007.079; at a level of 597.487 m. asl. This feature of dense, light gray loamy soil was laid out in an east-west orientation with a slight depression. On the south side, the feature was adjoined by an L-shaped layout of adobe bricks (locus 249), to the southeast, the area was adjacent to the rectangular niche (locus 251) of the structure in U-12. To the north, this feature was separated from a similar feature (locus 185) and by a partially preserved brick wall (locus 254). To the northwestern part of this area there was a feature containing a cluster of five gray mud bricks (locus 256) with an unknown function. In the northwestern corner, a brick and loam structure adjoined the site (Loci 257, 258). To the west, the area was slightly elevated. The western edge of the feature was rounded. At this end, the feature consisted of a thick loamy gray layer 6 to 7 cm thick. While clearing the paved loamy area, charcoal and charred wood of various diameters and sizes were detected throughout the area. The current interpretation of this feature is that it may be an outer courtyard to the structure of U-12, but it may also be part of a separate roofed structure or an extension to the structure of U-12. These hypotheses will have to be examined at a later date.